Opplyst liv

Kongelig prestedømme

Jeg hadde i dag gleden av å innlede et internasjonalt symposium ved St Mary’s University med tittelen ‘Christian Know Your Dignity’: The Royal Priesthood and the Renewal of the Church.

A passage from St Ephrem’s Hymns on Paradise often stirs in me. It reads like this:

God did not permit

Adam to enter

That innermost Tabernacle;

This was withheld,

So that first he might prove pleasing

In his service of that outer Tabernacle;

Like a priest with fragrant incense,

Adam’s keeping of the commandment

Was to be his censer;

Then he might enter before the Hidden One

Into that hidden Tabernacle.

Ephrem imagines all Eden as a sanctuary. Eden was for Adam and Eve before the fall ‘the world’, quite simply; the enclosure of beatitude within which their destiny was, by God’s design, to unfold. This sanctuary was divided into two: the outer and the inner tabernacle. The curtain dividing one from the other was represented by the tree of which man was not to eat — at that point the single commandment he had to observe. We know what happened. Not only did the intended passage into the inner sanctum not occur; by his fragmentation of intention man made himself unfit even for service in the outer tabernacle. He was excluded from Eden’s sanctuary altogether, its gate kept henceforth by cherubim wielding their turning, flaming swords.

For present purposes we might note two points from Ephrem’s account. First, man’s original existence is conceived of as having a priestly character. Its finality is worship, supremely exercised when man freely conforms his mind to that of his Maker and acts accordingly, so realising a grandeur in himself that, left to his own notions, he would never even have suspected. The second point is this: what exists, ‘the world’, exists in order to reveal ‘the Hidden One’. It is man’s singular mission to move from unseeing adoration to vision, to see God, and to make him seen, ‘as he is’.

Aspects of this priestly mission are manifest in the lives of the patriarchs. They proclaimed God’s name, invoking his presence in the land that was, as far as thistles and thorns would permit, to become Edenlike, a choice land. They prayed. They performed acts of sacrifice and dedication. They sought to know God’s will and to carry it out, to be a blessing, as the Lord had charged Abram already back in Haran.

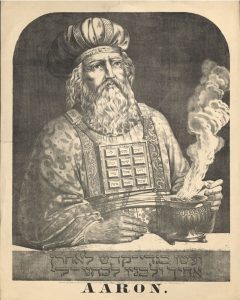

It was only after the exile in Egypt, however — during their return to the land, desired by some — spurned by others, that Israel was given a formal priesthood to epitomise and enact in the name of all their corporate vocation. The rationale for this institution is given in the book of Exodus, which after the account of Aaron’s priestly commission speaks in disconcerting detail of the practical preparations needed to make ready for the cult and to furnish Israel’s sacristy. These chapter are not, perhaps, our favourite passages of the Bible for lectio divina; however, they merit attention. Permit me to hone in on a particular detail from the 28th chapter of Exodus, which itemises Aaron’s ‘glorious adornment’ required for his entry into the inner tabernacle.

The fact that such a place should exist, that the mystery of God-with-us should become spatial reality, marks a revolution in the economy of mercy. Henceforth Israel would know where God could be found, adored, and besought, at least as long as they remembered him and his deeds on the people’s behalf: we know that only a few generations later, when the renegade sons of Eli, Hophni and Phineas, exercised the priesthood at Shiloh, the ark which represented God’s presence in the tabernacle was regarded as little more than a talisman. No one seemed to miss it much when it went missing in battle against Philistine forces. Even when it returned to Israel, the ark spent a good while in oblivion parked in Abinadab’s dismal house on the hill.

The Exodus account, however, stresses the tabernacle’s sublimity. Aaron’s first entering it marks a decisive stage in the restoration to mankind by grace of what Adam had lost in justice’s name. Aaron was gloriously robed to face God invisibly enthroned on the ark’s mercy seat. The Septuagint calls this seat hilastērion. It is, as you know, the term Paul would later use, in his letter to the Romans, as a designation for Christ, ‘whom God’, he wrote, ‘put forward as a hilastērion by his blood’. The word can be understood as both the sacrifice and the place of atonement, indicating the totality of the oblation that sealed the new and eternal covenant.

Foremost on the list of Aaron’s priestly garments is his breastpiece. The specifications for confection read like a litany. The breastpiece is to be made of gold, blue, purple, and scarlet stuff, fine twined linen, a span in length and breadth.

And you shall set in it four rows of stones. A row of sardius, topaz, and carbuncle shall be the first row; and the second row an emerald, a sapphire, and a diamond; and the third row a jacinth, an agate, and an amethyst; and the fourth row a beryl, an onyx, and a jasper; they shall be set in gold filigree. There shall be twelve stones with their names according to the names of the sons of Israel; they shall be like signets, each engraved with its name, for the twelve tribes.

Putting on this singular garment, Aaron would always, each time he entered the holy place, bear Israel’s sons’ names on his heart in ‘continual remembrance before the Lord’. They were to be lodged there, on his heart, together with the Urim and Thummim, priestly devices for obtaining oracles and for distributing judgement, ‘thus Aaron shall bear the judgment of the people of Israel upon his heart’. He is to be a conduit recalling to the Lord Israel’s needs and to Israel God’s standard of justice.

In the New Testament the apostles appear as successors to Jacob’s sons, called to engender an ecclesia embracing potentially all mankind. It is wonderful that in the Bible’s last book, the Apocalypse, we find this new humanity’s home, the eschatological city of the New Jerusalem, surrounded by walls that are adorned in a way that recalls the high priest’s breastplate pretty exactly:

the first [wall] was jasper, the second sapphire, the third agate, the fourth emerald, the fifth onyx, the sixth carnelian, the seventh chrysolite, the eighth beryl, the ninth topaz, the tenth chrysoprase, the eleventh jacinth, the twelfth amethyst.

On the walls are ‘the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb.’ They correspond to those of Jacob’s sons engraved on the gems of Aaron’s garment. To be a citizen of the New Jerusalem is to exist by conflating these two models of design: that of the breastplate and that of the city. It is to reside within the very heart of him who perfected and fulfilled what Aaron had foreshadowed. It is to be configured to him who proved himself perfectly obedient to the Father’s will, pouring himself out in love to the end, thus restoring man’s innocence.

Subsisting within the breastplate, building up the city whose light is the Lamb, we are graced to regain a priestly dignity and purpose that were ours at the first. We have the consolation of being remembered in Christ’s heart. At the same time we are agents of remembrance in his name on behalf of all the names entrusted to us, the names of all those whose lives have impacted on ours, in the hope that none might be forgotten, none lost; that mercy might extend to all. We are to pour out our lives in communion with Christ for that noble cause in sacerdotal compassion. Such is the nature of a priestly people destined to become a single priestly body.

It is tremendous and exciting that this mystery is the focus of our conference, rich in substantial contributions and in promise. We are invited to pursue our reflections in view of ‘the renewal of the Church’. It is an urgent purpose. May these days serve it well. And may we, with hearts renewed, discover the joy of swinging Adam’s censer and perhaps even catch a glimpse of the inner Tabernacle.