Ord Om ordet

23. søndag A

Preken holdt ved den engelske messen kl. 18.

Ezekiel 33:7-9: If you do not warn the wicked man, I will hold you responsible.

Romans 13:8-10: Owe no one anything, except to love one another.

Matthew 18:15-20: If your brother does something wrong, have it out with him.

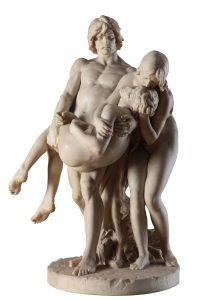

We’ve been told: ’If your brother does something wrong, go and have it out with him alone.’ This commandment is rooted in a Biblical story. The history of our race begins with a conflict between brothers that ended in tragedy. Once Adam and Eve had been exiled to the land of thistles and toil, Cain and Abel, their sons, grew up to be, one a tiller of the soil, the other a keeper of flocks.

One day they both bore an offering to the Lord. Abel’s was accepted, Cain’s rejected. Cain, humiliated and enraged, raised his hand against his brother and killed him. When the Lord asked, ‘Where is Abel, your brother?’, Cain answered fiercely, ‘Am I my brother’s keeper?’

Such is the origin of society, wounded by jealousy and shirked responsibility. Cain’s response resounds throughout history wherever one man knowingly humiliates, abandons, or destroys another. We may hear it in the secret of our heart, when prospects of advantage, or the desire quite simply to be left in peace, tempt us to ride roughshod over our brother or sister.

Am I my brother’s keeper? Why should I be?

The story of Israel is the story of the process by which the Lord forms a people out of such ice-cold isolation. The words addressed to Ezekiel in our first reading mark an important stage in that process. The Lord had appointed him sentry to the House of Israel. He was to make God’s warnings heard. But that was not all:

If I say to a wicked man: Wicked wretch, you are to die, and you do not speak to warn the wicked man to renounce his ways, then he shall die for his sin, but I will hold you responsible for his death.

The moral responsibility of the prophet is immense. His life is at stake. Israel’s destiny is his destiny. He is to let even the most hardened sinner know that God’s wrath is not irrevocable, that mercy may always prevail. Woe to him if he does not make a possible new beginning known! Should he fail in his concern for the brethren, should he abandon them to their destiny — their self-inflicted destiny — he himself will die.

We are being taught something essential about divine justice. It is justice not satisfied with rewarding the good and punishing the wicked. ‘I do not desire the death of the sinner, but rather that he should turn from his wickedness and live.’ Ezekiel is taught to make that agenda his own. Can I say it is mine? Can we say it is ours? Or do we secretly take satisfaction in the sinner’s condemnation and spiritual death? Who am I, after all, to be my brother’s keeper? Our response to the moral downfall of another provides a reliable indicator of our own state of soul. It tells us whether we have even begun to live according to God’s word.

Christ tells us all: ‘If your brother does something wrong, go and have it out with him alone.’ We must see those words in the light of the parable about the speck in our brother’s eye, the beam in ours. Christ is not talking about falls of which our brother is aware, from which he already struggles to rise. Nor is he concerned with behaviour that is irksome (to me) but morally indifferent. At stake are occasions when a person’s life takes a direction fundamentally opposed to God’s law and human dignity.

We may slip into death-dealing patterns of acting and thinking and deceive ourselves meanwhile into thinking that white is black, black white. Should we find our brother endangered by such blindness, we’ve the duty to go and have it out with him, while showing discretion and ensuring that our intervention springs from genuine concern for his good, not from my self-righteousness. In this way ‘we may gain our brother’, bringing him back from the precipice. We might hope our brother would likewise seek to gain us, should we be the ones at risk.

We cannot take away another’s freedom or force him or her to act in a certain way. Nor can we simply look on resigned while someone self-destructs. At least we should call out: ‘Come back, in Christ’s name, I’m here for you!’

A few days ago the Church commemorated St Gregory the Great, a great-souled monk and pope. St Bede tells us that the young Gregory was tortured by the thought of men and women in his own day living unenlightened by Christ, ignorant of God’s mercy. So touched was Gregory that he was prepared to leave the securities of a tranquil existence to become a herald of the gospel to the ends of the earth. Today we are asked to pause and examine ourselves in this respect. Are we concerned about the spiritual welfare of the people who surround us? Do we translate our concern into acts?

In his acceptance speech on receiving the Nobel Peace Prize in 1986, Élie Wiesel said: ‘The opposite of love is not hatred. The opposite of love is indifference.’ His words accord with Scripture’s message. We are charged on apostolic authority to ‘owe no one anything, except to love one another’. So, am I my brother’s keeper? Of course I am. And he, thank God, is mine.

A textual footnote: most modern translations will render Mt 18:15 as ‘If your brothers sins against you‘, which presents a different scenario. The ‘against you’ is absent, however, from many manuscripts; the root meaning of the admonition seems to be ‘If your brother goes off track’, i.e. is set on a path of wrong. The key challenge remains the same: that of doing what we can to orient another from darkness to light, towards the good and true.

Ce groupe d’inspiration biblique met en scène Adam et Eve portant leur fils Abel, victime de la jalousie de son frère Caïn. Médaille d’honneur au Salon de 1878, le modèle en plâtre est alors considéré comme « la manifestation la plus haute des sentiments que peut exprimer la sculpture ».