Ord Om ordet

31. søndag B

Deuteronomy 6:2-6: Listen, Israel!

Hebrews 7:23-28: This high priest can never lose his priesthood.

Mark 12:28-34: After that no one dared to question him any more.

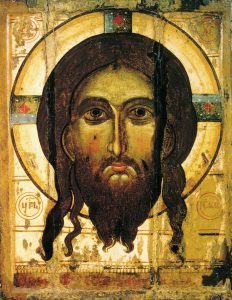

One of the earliest visual representations of Christ is the icon known in the East as the Icon-Not-Made-By-Hands. Its story is traced back to the first-century Syrian King Abgar, who in response to a letter he wrote to Jesus, inviting him to visit, received a towel with which the Saviour had dried his face after washing. It bore the imprint of his features. Abgar adorned the image and placed it over the city gate in Edessa, so the story goes. Eventually copies were spread throughout the Christian world.

We can leave it for another day to test the specific claims of this story. What matters is the role played, from the early days of our faith, by the contemplation of Christ’s face. The cry, ‘Show me Lord, your face’, runs through the Old Testament like a refrain. It resounds with insistence in the Psalms. In the Pentateuch, only Moses is said to have spoken to the Lord ‘face to face’ (Exodus 33:11). His own countenance was troublingly radiant as a result. The recognition that, in Jesus, the face of God had assumed human features enchanted the Church as it came to understand ever better who the Son of Man is.

To look into this face is to see eternity. Its facets are endless, its beauty fascinating. At different times, the faithful have focused on different aspects.

The murals of the catacombs show us the face of the Good Shepherd. The persecuted Church found comfort in this manifestation of Christ pledging to be with his people as they traverse the valley of death, to place the lost on his shoulders and carry them home, to separate, in due course, the sheep from the goats. As the faith became more established, divergent trends arose. In the Orient, iconography favoured the image of Christ’s face as Pantokrator, the eschatological judge enthroned in judgement with an open book, often portrayed in the dome of churches, above the space where the faithful receive communion. In the West, the face of Christ crucified became the motif of predilection. It made people mindful of his suffering ‘for our sake’. Post-Reformation Catholic piety focused on the Eucharistic Christ, stressing the reality of transubstantiation in the face of rationalist interpretations. And our own times? It is hard to say. We’ve largely lost the sense of Christ’s Passion. We don’t like to think of him as Judge. We tend to blur his features, I fear, into those of a kindly but bland bureaucratic humanitarian. Otherwise we project our face onto his. The fact that our portrayal of him has become so unspecific may explain why it carries so little appeal abroad.

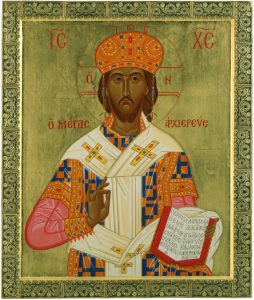

It is time, I’d say, to seek the Lord’s face afresh, even as we must pay fresh attention to his words. Our reading from Hebrews puts a neglected perspective before us. It shows us Christ as High Priest. Is that not an image to consider more often?

The seventh chapter of the Letter to the Hebrews is a glorious disquisition presenting Christ in the light of the figure of Melchizedek, the king of Salem who brought out to Abraham gifts of bread and wine, laying the foundation, we are told, for the biblical line of priesthood by which God’s grace is conveyed through human agency, made palpable and blessedly objective, effective no matter what suppliants feel like.

Melchizedek, remember, ‘is without father or mother or genealogy, and has neither beginning of days nor end of life, but resembling the Son of God he continues a priest for ever’ (Hebrews 7:3). We’re presented with the idea of a sacrifice unfolding beyond time and space, a quantum energy that carries and contains all that exists. Christ exercises, by virtue of his self-offering, a boundless mediation apt to ‘save’, that is, to transfer from the reign of death to eternal life, ‘those who draw near to God through him’. Indeed, ‘he always lives to make intercession for them.’ By his wounds we are healed; indeed, by his wounds healing assumes cosmic dimensions.

We are put on our guard these days against clericalism. That is quite right and thoroughly evangelical: we make ourselves absurd, and compromise the Gospel, if we don’t see beyond the micro-focus of tithing rue and mint, if our hearts pant for no more than ‘the best seat in the synagogues and salutations in the market places’ (Luke 11:42f.). But let us for goodness’s sake reboot our understanding of Christ’s priesthood and root ourselves within its logic of oblation. You have come to this place, dear seminarians, because you have heard Christ’s call: ‘Follow me’. If the call is certified, then confirmed by the Church’s ordination, your task will be not just to advertise Christ, as if you were his marketing agency. Certainly, a priest must preach, teach, and do all sorts of good. But above all he must be caught up in Christ’s ever-present sacrifice for the redemption of the world — caught up in it with his entire being, soul, mind, and body. Only by living an oblative life in this way will you receive the joy, strength, and freedom by which your enterprise comes to bear much fruit. What matters is not so much our jumping through multiple hoops as Christ’s work in us, transfiguring our poverty through his unsearchable riches.

Do we not, as Catholics, look at ourselves in the mirror rather too much these days? It is very boring, very counter-productive. So here’s a suggestion: Let us drape our mirror with Abgar’s cloth and seek the face of Christ instead, to see him as he is, looking at us at once with priestly majesty and the victim’s meekness, saying ‘I no longer call you servants, I call you friends’. Amen.