Ord Om ordet

Br Jonathan Gell RIP

Sirach 2:1-11, 17 Who ever trusted in the Lord and was put to shame?

2 Corinthians 4:7-12 So that the life of Jesus may also be manifested in our bodies.

Matthew 17:1-12 The disciples fell on their faces and were filled with awe.

The Lord’s Transfiguration is a cardinal event in the Gospels. The word ‘cardinal’ may make us think of scarlet silk and conclaves, but what I have in mind is a more radical sense of the word. In Latin, cardo means ‘a hinge’; to be cardinalis is to be that on which something turns. The Transfiguration divides Jesus’s life prior to the Passion into a definite Before and After, like panels in a diptych. Before they followed him to Tabor, the disciples had seen Christ work miracles and healings. They had heard him speak wonderful words. They had learned to love and trust him as their Master. On the mountain they saw what they had started to intuit, but did not dare believe. They saw Jesus radiant with uncreated light, ‘his face like the sun’. Their very senses perceived the essence of our faith: the sublime, shocking fact that in Jesus, God is corporeally present. The Lord’s glory, which even the blessedest of patriarchs glimpsed but in passing flashes, stood before them as a solid presence. Awestruck they fell to the ground. ‘Who can see God’s glory and live?’ For the rest of their lives they pondered that scene. ‘We were eyewitnesses of his majesty’, wrote Peter: ‘we heard [the Father’s] voice from heaven, for we were with him on the holy mountain.’ From thenceforth, the three elect disciples, Peter, James, and John, were in a state of discomfiture. They had seen God’s glory in perfect clarity, but had to re-descend into the valley of human confusion. They had tasted eternity, but must drink to the dregs the chalice of life’s passing, which for two of them culminated in a martyr’s death. They must work out (first in their minds, then by living) that mysterious word Jesus spoke on their way down from Mount Tabor: ‘the Son of man will suffer.’ Far from shielding him from pain, the transfiguration prepared Christ for his Passion. And as John later said, any woman or man who would be his disciple must walk ‘in the same way in which he walked’.

The disciples’ sense of displacement leaves its mark on every Christian life. All of us are stretched between the freedom and grace won for us by Christ and the constraints, sometimes cruel, of day-to-day life. Some people, though, are called to endure this conflict more intensely than the rest of us, as living signs of the pathos and grandeur of the Christian condition in its height and depth, length and breadth. Our Brother Jonathan, whom today we lay to rest, was one such. His life was a life of great suffering. Physical illness left him almost a cripple. He knew, too, the searing pain that can afflict mind and soul. For long periods he was engulfed in shattering, all-embracing darkness. And yet, he was a witness to the light. I would say more. I would say that sometimes he himself seemed almost luminous. He was possessed of a joy, a lightness, and a strength that made him appear, right to the end, the bearer of some glorious secret. What was that secret of his? Can we dare to try to put it into words?

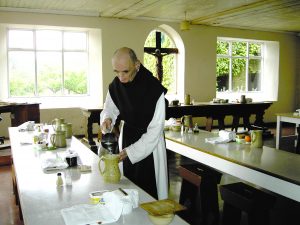

The defining fact of Brother Jonathan’s life was his gift of himself to the Lord. He renewed that gift constantly, especially in times of trial. He kept nothing back. His was the confident giving of a child. Like a child, he fully expected the Lord to provide what he needed. ‘Help!’, he would say, knowing he would be helped. Brother Jonathan had a keen sense of God’s majesty. At the same time he spoke to his Maker familiarly. When we asked, towards the end, whether he felt like having supper, he might say, ‘I was just speaking to the Lord about that’. I am sure he was. And it was no banal conversation. It was an indication of the fact that, for Jonathan, everything was charged with the reality of God. He had a flair for finding mystical meanings in humdrum circumstances, not least in his long service as our refectorian. In the midst of, say, clearing the breakfast things away, he would discourse on deep mysteries with vigorous gesticulation, often forgetting he still held on to his industrial cheese cutter, so exposing the rest of us to risks of decapitation. In small things and great, Jonathan, that great enthusiast, sought God and found him. This gave him a dignity that was peculiarly his. It gave him fortitude. Though often in pain, he never complained. He was a cheerful, gracious man.

A second feature that defined Jonathan was his humility. There was nothing grovelling about it. It did not keep him from being quite firm at times. It was rather a resolute acceptance of things as they are. Even as he knew how to give, he knew how to receive, and did not presume to accept some gifts as good while discarding others as bad. He chose all, receiving all with gratitude. He never tired of saying, ‘Thank you’. He had a gift for amazement. He would often say, ‘I am having a most extraordinary time!’ What that referred to was variable. It could be a fresh insight into the mystery of the Trinity or the fact that a fly had settled on his nose. All was gift to him, and wonder. Everything was potentially sacramental, tinged with glory. Far from trivialising exalted things, this mindset of his made humble things exalted. For Jonathan, Tabor was always within sight, even when no one else could, or would, see it.

Finally, it is impossible to speak of Jonathan without evoking his love of the Church. His Catholicism was constitutional. He loved the Holy Father. He loved the CTS. He loved the Osservatore Romano very much. In and through these elements, he loved the communion of saints and the Mystical Body. Living close to the heart of the Church, he keenly felt the Church’s wounds. It is striking that this dear man, who knew such divisions in himself, should devote his life to fervent prayer for Christian unity! That cause imbued his darkness with light and transfigured it. As for the Church in its immediate manifestation, all of us know how dearly Jonathan loved the monastery of his profession. He was, like our first Cistercian fathers, a true ‘lover of the place and of the brethren’. His devotion to the community knew no bounds. He was always keen to serve. He always wanted to be with the brethren. As today we bury his mortal remains, let us pray that he will continue to keep close to us. Let us trust that the Lord will admit him, now, to the angelic choir – to sing in tune at last! Praised be God for the wonderful, mysterious, delightful gift of Brother Jonathan’s life, for his example of fidelity. May we one day be united with him, as one, in the worship of God’s glory, face to face. Amen.