Ord Om ordet

Feria vj, uke iij (2)

There is an English translation underneath the Italian text

Ezechiele 17:22-24 Umilio l’albero alto e innalzo l’albero basso

Marco 4:26-34 Il regno di Dio è come un granello di senape

Per orientarsi nel mondo, l’uomo lo nomina. Questo procedere corrisponde al suo bisogno e alla vocazione rivoltagli da Dio quando, all’inizio, condusse ad Adam gli animali ‘per vedere come gli avrebbe chiamati’. Un aspetto splendido della vita è l’imparare a chiamare l’universo per nome — veder tel fiore e sapere che è una primula polyantha; trarre dall’anonimato anche elementi dell’immensità cosmica che ci circonda. ‘Il crescere della conoscenza non si ferma’, osserva Carlo Rovelli in un libro che ho letto questa settimana. Il genio umano è arrivato a distinguere persino i tipi di particelle ‘che si combinano insieme all’infinito come le venti lettere di un alfabeto cosmico per raccontare l’immensa storia delle galassie.’

Questo lavoro ermeneutico è grandioso e nobilissimo quando si conduce con dovuta umiltà. E’ pericoloso se ci ispira l’illusione che noi, avendo chiamato qualcosa per nome, sappiamo cosa sia. Nominando una cosa, posso aver l’impressione di impadronirmi di essa, come fossi io un demiurgo traendola dal non esistere. Cresce in me l’illusione di onnipotenza.

Applicata alle relazioni umane, un tale atteggiamento diventa disastroso. In quanto assumo il diritto di categorizzare le persone, applicando a loro etichette identificatorie, le considero mie creature. Faccio prova di una prepotenza luciferiana.

Tutti sappiamo come funziona la dinamica. Rimaniamo vulnerabili alle proiezioni altrui. Qualcuno ci dice, ‘Non sei capace di nulla’. Integriamo l’affermazione come fosse un oracolo. Ci dicono, ‘Sei un genio, capace di tutto’. Noi ci crediamo — e l’effetto dannoso è potenzialmente altrettanto grande.

Imprigioniamoci, e imprigioniamo gli uni gli altri, in categorie strette e banali, gli occhi del cuore chiusi al mistero che l’altro rappresenta, che io stesso incarno, rifiutando la possibilità di quel continuo divenire che il Creatore desidera per ciascuno di noi.

Perciò Cristo, il Verbo incarnato, nella cui immagine siamo creati, trova le sue delizie nel confondere le nostre idee. Libera il nostro pensiero. Nel vangelo, il Signore ci presenta le sue tante parabole di crescita organica per farci uscire da nozioni cerebrali paralizzanti. Chi avrebbe creduto che un granello di senape porti in se la possibilità di un albero maestoso?

Sempre di nuovo dobbiamo imparare a stupirci davanti alla vita che germoglia, cresce e fiorisce inesorabilmente anche mentre noi siamo affondati nella letargia.

L’altezza dell’albero che permette agli uccelli di fare il loro nido presuppone la profondità delle radici. L’albero alto di per sé non deve impressionarci, specie se è cresciuto troppo velocemente. E’ bello, sì; ma se non è solidamente radicato rimane fragile, atto a cadere. La sua rovina rischia di essere grande. ‘Io’, dice il Signore, ‘umilio l’albero grande e innalzo l’albero basso’.

‘Umiliando’ l’albero grande lo riporta nel humus. La sua intenzione è di preparare così, non soltanto un aspetto imponente, ma una fecondità stabile. Negli affari umani, Dio agisce nello stesso modo, rovesciando i potenti dai troni, innalzando gli umili.

Fratelli e sorelle: ringraziamo Dio quando lui, da coltivatore responsabile, ci fa subire una buona potatura, quando riscava il terreno in cui siamo piantati, magari mettendoci addosso una buona carrata di letame. Così cresceremo. Così diventeremo capaci di portare frutto per il regno del cielo, frutto abbondante e nutriente, frutto che rimane. Amen.

English version

In order to find his place in the world, man names it. This procedure corresponds to his intimate need. It correspond, at the same time, to the task God set him when, in the beginning, he led all moving creatures before Adam, ‘to see how he would name them’ (Den 2:19). The gradual process of learning how to call the universe by name is magnificent: to see one flower among others and to know it is a primula polyantha; to draw out of anonymity even elements of the cosmic vastness surrounding us.

‘The accumulation of knowledge never ceases’, writes Carlo Rovelli in his Seven Brief Lessons on Physics. Human genius has reached the point of being able to distinguish even the types of particles ‘that are infinitely combined, like the twenty letters of a cosmic alphabet, to tell the immense history of the galaxies.’

This hermeneutic enterprise is grandiose and noble when conducted with due humility. It is dangerous if it gives rise in us to the illusion that, because we can call a thing by name, we know fully what it is. By naming something, I can delude myself that I am that thing’s master, as if I were a demiurge drawing it out of non-existence. I yield to the dream of omnipotence.

When this kind of attitude is applied to human relations, it becomes truly disastrous. In as much as I claim the right to put others into boxes, covering them with identify-fixing labels, I consider them my creatures. I give evidence of Luciferian pride.

We all know how these dynamics work. Someone says to us: ‘You are good for nothing!’, and we interiorise the affirmation as if it were an oracle. Someone says to us: ‘You are a genius, capable of anything!’, and we fall for it. The harmful effect of this second delusion is at least as great as that of the first.

We imprison ourselves and each other in narrow, ridiculous categories, our heart’s eyes closed to the mystery represented by each person – the mystery I embody myself – refusing to admit the continuous becoming that is the Creator’s will for each one of us.

That is why Christ, the incarnate Word, in whose Image we were made, delights in confounding our ideas. He liberates our thinking. In the Gospel, the Lord presents his parables of organic growth to rescue us from paralysing cerebral notions. Who would have thought that a mustard seed could turn into a majestic tree?

Again and again we must learn to wonder at life, the way it sprouts, grows, flowers, and bears fruit inexorably, even while we rest in the embrace of lethargy.

The height of a tree that permits birds to make their nests in it (Mark 4:31) presupposes the depth of that tree’s roots. The tallness of the tree as such should not impress us, especially not if it has grown too quickly. It is a sight to behold, by all means! But if it is insufficiently rooted, it is apt to fall. Its fall risks being great. ‘I bring low the high tree’, says the Lord, ‘and make high the low tree’ (Ezek 17:24).

By ‘bringing low’ the tree that is tall, he strengthens its connection with the humus; quite literally, he ‘humiliates’ it, his intention being, in this way, to assure, not merely an imposing appearance, but stability and fruitfulness over time.

In human affairs, the Lord works similarly, ‘casting the mighty from the thrones and exalting the lowly’ (Luke 1:52).

Brothers and Sisters: let us thank the Lord when he, like a good orchard keeper, subjects us to a thorough pruning, when he re-digs the soil in which we are planted and graces us with a cartload of dung. That is how we will grow. That is how we will bear fruit for the kingdom, abundant and nourishing fruit, fruit that will last. Amen.

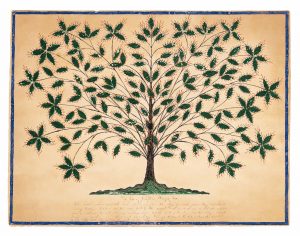

The illustration shows the Tree of Life drawn in 1845 by Hannah Cohoon, a member of the Shakertown Community in Kentucky.