Ord Om ordet

Om å se og tro

John 6.35-40: Whoever sees the Son shall have eternal life.

It is said that ‘seeing is believing’. The Gospel tells us this is not always the case. Jesus says: ‘You can see me and still you do not believe’. At the same time, he stresses that faith cannot be isolated from sight if it is to have salvific benefit. Sight and faith work in concert: ‘It is my Father’s will that whoever sees the Son and believes in him shall have eternal life.’ Such a one, ‘having eternal life’, Christ will raise up on the last day.

Of course, there’s seeing and seeing. One can have perfectly good eye-sight and yet not perceive. In antiquity seeing was seen as an intellective faculty. The acquisition of truth-conveying sight was tantamount to inward illumination, a capacity to recognise things, material or abstract, as they are. It is an imaged way of thinking we still use, as when, on understanding something we say, ‘Ah, I see!’; or when we are perplexed by another’s claims and say, ‘I don’t see how you can state such a thing.’

Western philosophy since Descartes has tended to assume that the perception of reality results from inference; that I can, in isolation, think my way to the truth. The Gospel’s philosophy is different. It submits that truth is discovered by way of encounter.

For the truth, in Christian terms, is no concept, but a personal presence, a presence capable of saying, ‘I am’ — ‘I am the truth’.

Jesus’s Pasch is reflected on in Scripture through accounts and metaphors of seeing and non-seeing. Jesus foretells his Passion saying: ‘A little while, and you will see me no more; again a little while, and you will see me’ (John 16.6). The last sign he performs on the way ‘up to Jerusalem’ is the healing of blind Bartimaeus, who cries out, ‘Lord, that I may see!’ (Mark 10.51). The pilgrims to Emmaus, lacking faith, fail to see the risen Lord; when faith is restored to them in bread-breaking, sight comes, too (Luke 24.13-32). Thomas, patron of sceptics, states his ultimatum: ‘Unless I see the holes that the nails made, I will not believe’ (John 20.25). He does see and believe; even as John, who tells the story, had earlier looked into the empty tomb, seen and believed (20.8).

Is is, then, of capital importance to learn to see rightly. It is crucial to remove from our spiritual sight cataracts of sin, cynicism, and fear, to purify our hearts, to practise seeing even in the night, in darkness, to seek the one we love (cf. Song of Songs 3.1). For our eyes shall see, not another (cf. Job 19.27).

What we see in truth transforms us. If what we see is Truth, Truth confirms its image in us and fashions its likeness. That is the beginning of ‘eternal life’, a pledge of resurrection.

Those who see in this way become radiant (Psalm 34.5). No mere argument for our religion will open other’s eyes more effectively than such embodied radiance.

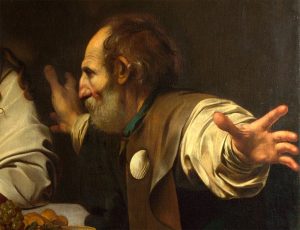

One of the Emmaus pilgrims coming to sight, with shells falling from his eyes, in Caravaggio’s account, now in the National Gallery.