Ord Om ordet

Hl Simon og Judas

In the tenth chapter of the book of Genesis, we are told how, once Noah’s Ark was settled on firm ground, his sons scattered over the face of the earth. So closely were various parts of the inhabited world linked with them and their descendants that geography and ethnography become one in later biblical narrative, exactly as it would a many centuries later, when Israel’s sons inhabited the Land of Promise. Personal names are irrevocably connected with places.

In the early Church, lists of Jesus’s Apostles evoked similar associations. We associate Rome with Peter, Egypt with Mark, India with Thomas, Malta with Paul, and so forth. True to Christ’s commandment the Apostles scattered to the north and south, east and west. Like Noah’s children, and Jacob’s, they represented a new humanity. That new humanity had to spread everywhere, lest the light of Christ should be hidden under a bushel.

It is fashionable these days to say we not know nothing about the later life of the apostles, that these men, so characteristically present in the Gospels, vanish into thin air after the Ascension. That is what sceptics maintain who have no time for tradition.

But perhaps we need not be quite so reductive?

The Apostles we celebrate today, Simon and Jude, are in very ancient sources associated with a mission to the East. A venerable document of early Church history, the Doctrine of Addai, tells us how Jude, also known as Thaddeus, or Addai in Syriac, was despatched by St Thomas to Edessa in modern-day Turkey. There his preaching and works of healing brought about the conversion of the city. Let the doubter doubt. The fact remains that Christianity was established in that part of Mesopotamia by the early second century with a firm claim to Apostolic origins. Someone must have brought it there, and Thaddeus’s name is connected with the mission from the first.

An impressive feature of the Doctrine of Addai is the Apostle’s serene self-consciousness. He knows he is carrying an infinitely precious message; at the same time he is entirely uninterested in any honour for himself. He does not even bother to make a display of his humility. So obvious is it to him that his person is of no consequence. What matters is the word entrusted to him, the spiritual power he dispenses. At one point, King Abgar of Edessa wants to pay Thaddeus gold and silver for his benefits to the city. Thaddeus calmly retorts, ‘If we have left our own property behind, how can we accept other people’s?’

It is not strange that this humble man should gradually disappear in the mist of history. He was concerned to bestow Christ, not to leave traces of himself. He lived out the principle of all Christian mission: ‘He must increase, I must decrease.’ He was determined to remain poor and transparent, to be a voice crying in the wilderness, not a protagonist accumulating thousands of ‘likes’ on Facebook. In that respect he remains a timeless example to us all.

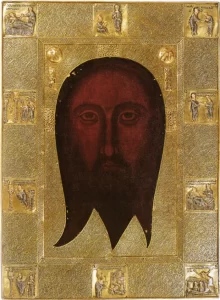

The Mandylion of Edessa. The foremost relic of the evangelisation of Edessa is an image of the face of Christ, not an ‘I was here’ signature of the Apostle. That says something.