Seeing

Reading Czesław Miłosz’s Nobel Prize Lecture from 1980, I am struck by this paragraph: ‘One of the Nobel laureates whom I read in childhood influenced to a large extent, I believe, my notions of poetry. That was Selma Lagerlöf. Her Wonderful Adventures of Nils, a book I loved, places the hero in a double role. He is the one who flies above the Earth and looks at it from above but at the same time sees it in every detail. This double vision may be a metaphor of the poet’s vocation. I found a similar metaphor in a Latin ode of a Seventeenth-Century poet, Maciej Sarbiewski, who was once known all over Europe under the pen-name of Casimire. He taught poetics at my university. In that ode he describes his voyage – on the back of Pegasus – from Vilno to Antwerp, where he is going to visit his poet-friends. Like Nils Holgersson he beholds under him rivers, lakes, forests, that is, a map, both distant and yet concrete. Hence, two attributes of the poet: avidity of the eye and the desire to describe that which he sees.’ Our time needs such panoramic seers and careful describers.

Coppélia

Coppélia, first performed in 1870, the year of the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, tends to be advertised as a ‘comic ballet’ set to music by Delibes, of flower-duo fame. Coppélia is on the face of it absurd. A young man called Franz has the world’s loveliest fiancée, Swanilda. Everything is set for the wedding. But then Franz is intoxicated by a strange creature he sees in the village square, a life-like doll made by the local inventor-cum-magician Coppélius, who is untouched by human affections, living only for his designs. The drama of the ballet unfolds as Swanilda tries to win Franz back; yet such is Coppélia’s gracefulness that we are almost tempted to hope that Swanilda will fail and that love might somehow make the virtual real. This might all have seemed outlandish fantasy 150 years ago. Now the sight of a man made to choose between a virtual and an embodied-ensouled love is terribly real. I was struck by the power of this story when I saw it performed by students of the Roman Opera Ballet last week. Those youths showed us that the drama of Coppélia isn’t just some laughable drivel; it is the stuff of contemporary tragedy.

Canta et ambula

St Augustine’s sensitivity to music is well documented. In the Confessions he says how struck he was by the singing in the cathedral of Milan: ‘How I wept, deeply moved by your hymns, songs, and the voices that echoed through your Church!’ Better than anyone he has made sense of the jubilus in chant, ‘a certain sound of joy without words, the expression of a mind poured forth in joy’, joy that is ineffable, yet singable. Today, on the last day of the Church’s year, the Divine Office gives us another wonderful text on singing. Augustine speaks here of the kind of singing apt to keep our courage up as we pilgrimage towards hope in a world that often appears like a vale of tears. His words have great poignancy. They resound credibly still as the counsel of a father, a friend: ‘Always go onward in goodness, right faith, good habits. Sing, and walk onwards.’ Thus we shall be preserved from discouragement and pusillanimity.

Tolkien’s Creation

Asked by The Tablet to contribute to its annual Books of the Year supplement, I was happy to recommend a volume that has accompanied me for much of the autumn as I’ve been reading it in small chunks at breakfast: ‘What happens when a classical philologist turns his mind to the study of one of modern literature’s most audacious, best-loved enterprises? Read Giuseppe Pezzini’s Tolkien and the Mystery of Literary Creation to find out. The book is at once an overview of Tolkien’s work and an essay in literary theory. It is elegantly composed. And it’s fun. It will tell you at last what Queen Berúthiel’s cats are all about.’ Professor Pezzini’s book is eye-opening and ear-opening. He invites readers to listen again to the noise Frodo heard ‘in the distance. He knew that it was not leaves, but the sounds of the Sea far-off; a sound he had never heard in waking life, though it had often troubled his dreams. A great desire came over him to climb the tower and see the Sea.’

Uimotsigelig, ikke farlig

Blant de mange ting jeg ble slått av i Tordis Ørjasæters personlige historie «om annerledesbarnet i litteraturen», Vi er ikke alene, var denne beskrivelsen av Sigrid Undset, hvor hun deler et barndomsminne fortalt av hennes mann, Jo Ørjasæter: «Min mann Jo husket at han som liten gutt ble løftet av et stort og meget voksent og uimotsigelig, men ikke farlig menneske, og ble plassert i en lenestol med en billedbok eller leke. Sigrid Undset var ikke den som la seg på kne for å leke med barn eller snakke babyspråk. Derimot gav hun ham hver jul velvalgt sportsutstyr eller bøker.» Undset, hellig overbevist om at «moderskapet er livet», var fullstendig usentimental i forhold til oppgaven det stod for. Derved har hun noe viktig og originalt å si til vår tid.

Salige Niels Steensen

“Om dere holder ut, skal dere vinne livet”, sier Vårherre. Mange av oss vil ha erfart hvor sant det er, at de vesentligste tider i våre liv, tidene som virkelig formet oss, ikke nødvendigvis var tider da vi gjorde en masse, men tider da vi rett og slett holdt ut gjennom noe vanskelig: spenninger eller konflikter eller uvisshet, eller hva det måtte være. Som et bilde på frelse, snakker Skriften om gull i smeltedigelen. Da skal det tålmodighet til, for å la alt slagg smeltes bort. Men det som blir igjen, det holder. Helgenen vi minnes eksemplifiserer en slik prosess. Niels Steensen, født i København i 1638, var medisiner av internasjonalt ry, som gav karrieren på båten for å vigsles til prest, senere til biskop. Siden han en tid forvaltet bispedømmet Hamburg, med ansvar for Danmark og Norge, var han også vår biskop. Motstanden han møtte i sitt forsøk på å hellige Kirken og geistligheten, var stor. Hans helse var klein. Han reiste utrettelig, uten av den grunn å minske sin askese. Og hans blikk ble bare lysere og lysere. Da han døde, 48 år gammel, var han som en moden pære, rede til å plukkes. Vitenskapsmannen Steensen var sensibel for skaperverkets rikdom. Det gjør da inntrykk at han sa, “Skjønt er det vi ser; skjønnere er det vi erkjenner; skjønnest av alt, er det vi ikke fatter.” Måtte det gis oss alle å leve på den innsikt! Amen.

Erasmus Lecture

‘Transhumance, an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity since 2023, is by definition constant drifting across borders. If you are caught up in transhumance you do not stay behind a wall trying to work, or shut, out what people say and do on the other side; you move back-and-forth seeking sustenance in changing landscapes for yourself and your flock. Mireille Gansel develops the metaphor of transhumance in a twofold way. On the one hand, languages constitute pastures. Shepherded from one to the other is significant content — in a poem, novel, treatise, or confessional statement seeking new form. On the other hand, language itself can be thought of as a flock led from winter to summer grazing with the translator as its shepherd. Language, in this account, is a nomad reconciled to the transient nature of any ‘home’.’

From this year’s Erasmus Lecture, now available on YouTube.

Sr Anne-Lise RIP

Sr Anne-Lise Strøm ble begravet i dag. Hun døde forrige fredag, 85 år gammel. Mange er vi som vil savne henne dypt. Hun var et fullt ut hengitt menneske. I intervjuboken hun utgav i 1997 sammen med Brita Rosenberg, beskrev hun oppbruddet fra Oslo til Lourdes i 1961, da hun trådte inn hos de kontemplative dominikanerinnene der: ‘Toget satte seg i bevegelsen. Faren løp etter og ropte: «Anne, skriv!» Han gråt.’ Det syntes som om denne livsglade, oppvakte, begeistrede unge kvinnen var tapt for verden. Lite visste man. Gjennom et langt og trofast klosterliv, ble Sr Anne-Lise på mange vis den katolske Kirkes best kjente (og vel kjæreste?) ansikt i Norge. Utallige har hun rettledet, undervist, trøstet og oppmuntret med sin særegne blanding av realistisk klarsyn og urokkelig tillit til en forvandlende miskunn. Morsom var hun, dypt selvironisk; på samme tid uutgrunnelig og evighetsinnrettet. Vis ble hun av nåde og erfaring, et tvers gjennom elskelig menneske. Gud gi henne det hundredfold hun med hele sitt vesen formidlet!

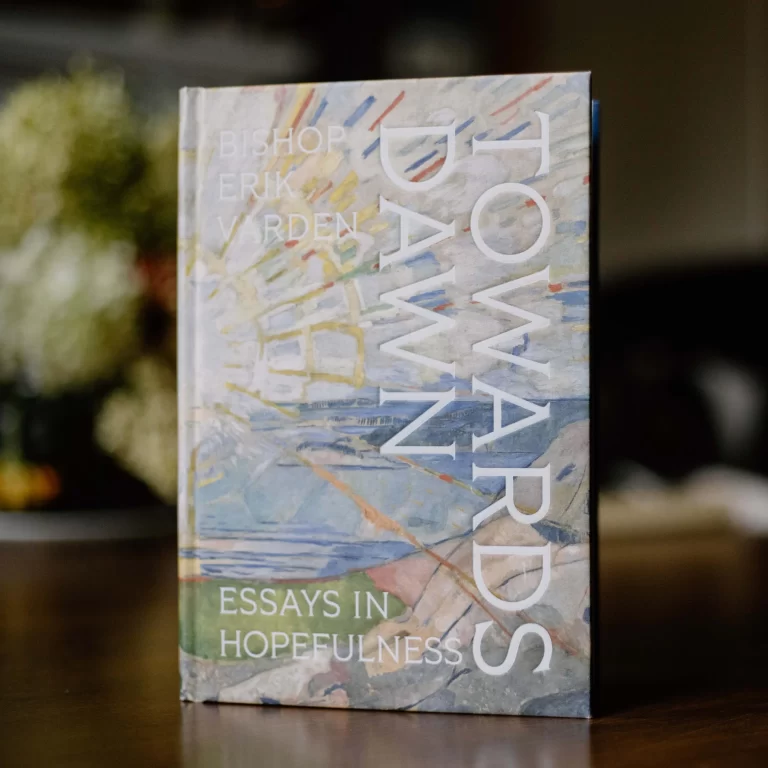

Towards Dawn

‘It is often casually said that we live in post-Christian times. I believe that statement to be false. Theologically, the term ‘post-Christian’ makes no sense. Christ is the Alpha and the Omega, and all the letters in between. He carries constitutionally the freshness of morning dew. Christianity is of the dawn. If at times, during given periods, we feel enshrouded by twilight, it is because another day is in the making. It seems to me clear that we find ourselves in such a process of awakening now. If we do want to deal in the currency of ‘pre’ and ‘post’, I think it more apposite to suggest that we stand on the threshold of an age I would call ‘post-secular’. Secularisation has run its course. It is exhausted, void of positive finality. The human being, meanwhile, remains alive with deep aspirations. It is an essential task of the Church to listen to these attentively, with respect, then to orient them towards Christ, who carries the comfort and challenge for which the human heart yearns.’ From my new book, Towards Dawn, just published. You can read more about it here.

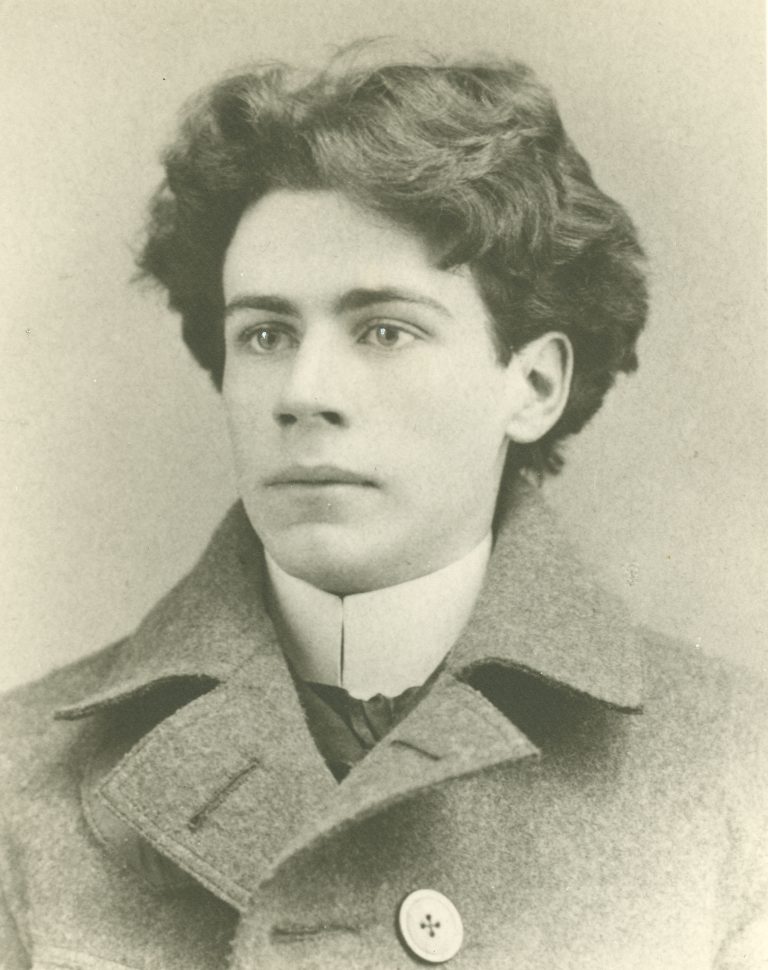

No Blond Skies

There is clearly a Norway of the imagination. An attentive reader, having seen my note on Emily Dickinson last week, sent me this supremely melancholy poem by the symbolist Émile Nelligan, who says of himself in a moment of near despair: ‘I am the new Norway from which the blond skies have departed’. Nelligan is a tragic figure in the literature of Québec. Afflicted with a bipolar condition he was hospitalised at the age of twenty and remained in institutions until his death at 44. He seems not to have known the soft luminosity that marks even the depths of Norwegian winter – not to mention the summer nights untouched by any darkness at all.

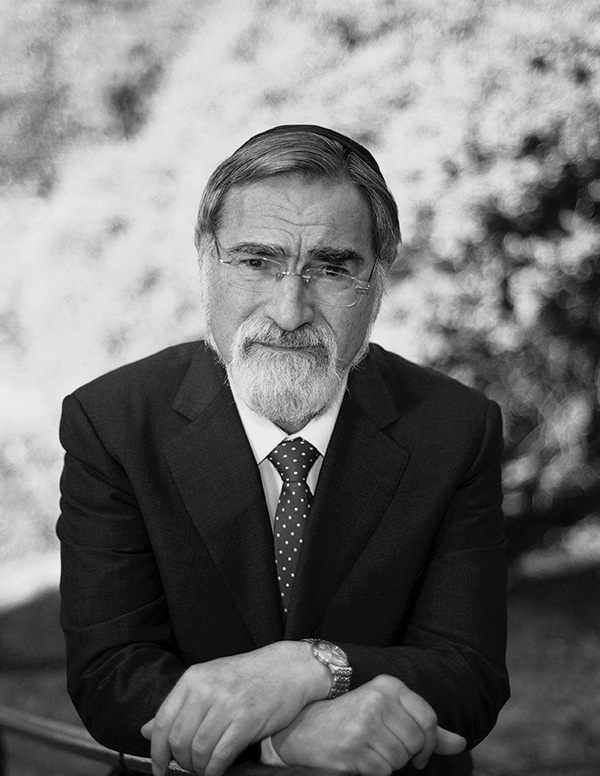

Antisemitism

Throughout the West, antisemitism, the world’s oldest hatred, is raising its ugly head, more or less sublimated in political terms, but instantly recognisable. Much is being written about this development. This is good. Wise heads must think together to counter a trend that lies within the body politic as a latent virus. In such straits I miss the intelligent, humane, fearless voice of Jonathan Sacks. Fortunately many of his videos and texts are available on a website dedicated to his legacy. Rabbi Sacks spoke of antisemitism as ‘the first warning sign of a culture in a state of cognitive collapse. It gives rise to that complex of psychological regressions that lead to evil on a monumental scale: splitting, projection, pathological dualism, dehumanisation, demonisation, a sense of victimhood, and the use of a scapegoat to evade moral responsibility. It allows a culture to blame others for its condition without ever coming to terms with it themselves.’ Those words were written ten years ago. Meanwhile they have only gained in relevance.

Psalmody

In a wise, poetic essay, Armando Pego describes a visit to an abbey where he delves into silence after a train trip alongside travellers full of that joy ‘only the sea can give’. They go on to ‘scatter like solitary starlings’; he, meanwhile, is bound for a definite goal: ‘At Poblet I find the rest the hours of the Office give. Along with a handful of guests, joined by more or less sporadic tourists, or on my own at daybreak or for None, I find myself on a pew distant from the choir, trying to abandon subjective pretensions. We live in times that give great weight to personal experience and sentiment, to that in our ego which is at the same most moving and most onerous. I wish to propose as counterweight an inner life alert to the objectivity of liturgy. I desire to stop being the centre; to lean towards the vertigo of God’s greatness. We can touch it, just about, through psalmody, which lets us glimpse it as a boundless fount of love. There is no trace of a concert or spectacle; there is no enthusiasm, no ecstasy. We make a superhuman effort to rise above our smallness, gathered as a community that, in unison, harmonises stammering. I always come out a loser. About to yield to discouragement, I console myself that I have had a lesson in humility. Had I been victorious even for a moment, it would all have been in vain.’ You can read the entire piece (in Spanish) here.

Translation Praised

‘Then, of course, there is Artificial, or Inhuman, Intelligence. Thanks to it, translation is mechanised. Feed in some verses by, say, Li Bai, a Chinese poet of the Tang Dynasty, and you find them spewed out in the twinkling of an eye in colloquial American, contractions and all. AI does not limit itself to rendering a given ‘foreign’ language into another. It offers to translate even the vaguest notions that arise out of our fancy’s pond-fog into cogent speech. As a result, we can increasingly dispense ourselves from coming up with our own words. There are, here and there, pragmatic advantages to this. But they come at the cost of catastrophic loss. For what will man turn into as he, formed in the image of the Word, surrenders poetry to algorithmic patterns, logos to digits, with everyone’s speech, everywhere, sounding the same?’

From this year’s Erasmus Lecture, to be published on the internet and in First Things in mid-December.

Norway of the Year

At about this time of year in 1865, Emily Dickinson wrote to her sister, Mrs. J.G. Holland, after an update on family news: ‘It is also November. The noons are more laconic and the sundowns sterner, and Gibraltar lights make the village foreign. November always seemed to be the Norway of the year.’ Like Sadie Stein I have loved those lines since I first came across them, I can’t remember when. Stein speculates about the source of Dickinson’s association: Asbjørnsen and Moe? Immigrants’ tales? One can but speculate. What we can say is this: November, as well as being a time when nature, through processes of death, prepares for sleep is also a time when fields are prepared for next spring’s crops, when the air has a blessed freshness that intensifies breathing, and when subtle symphonies of colours can make you gasp with wonder before dusk.

Acting Beautifully

In an essay about Eucharistic Traces in the work of Peter Handke, Jan-Heiner Tück shows how Handke evidences something of Guardini’s great intuition, that the Mass, by inculcating ritualised, deliberate movement, teaches us to engage beautifully with things.

‘One of the benefits of Holy Mass: I sit properly; I stand up properly, for instance when the Gospel is read; when the homily begins, I sit down properly again; during consecration I fall properly to my knees; while walking up to receive Corpus Christi I find my proper place in a line among other communicants; then I return to my pew by a proper detour.’

To point towards the educative impact of such experience is not pernickety; it is wise; it is to take on board what incarnation means.

War and Peace

For decades, Karl Schlögel has been among the lucidest, learnedest analysts of European historical trends. This week he was awarded the Peace Prize of the German book trade. His acceptance speech is a powerful summons to relinquish naivety and wishful thinking, to think hard and to act bravely: ‘And then it becomes clear that, despite all our knowledge, despite all the experience of previous generations, we must start again from scratch, and that our profound haplessness renders us incapable to describe what is going on before our eyes. The terms we use to describe the new circumstances are inadequate. We are at a loss for words to accurately convey what is happening. This is more than just a lack of concepts or writing skills; it is the loss of the horizon of experience that has formed us till now, a reality where everything we have accumulated over the course of a lifetime seems in question, devalued, even in ruins.’

Synodality

Some weeks ago I visited the abbey church of Otterberg in the Palatinate. It is what remains of a Cistercian monastery founded in the 1160s. Now it serves as joint parish church for a Lutheran and a Catholic parish. The proportions are perfect with gracious aisles, ideal for the processions that were such an important part of the Order’s liturgical life. What chiefly impressed me, though, was this confessional with its metal sign: ‘All Sinners Welcome!’ The exclamation mark is eloquent. It calls out to sinners, ‘You’re one of us – you belong!’ – a sentiment that, if it is sincere, preserves the Christian community from tedious conceit. It struck me as a criterion for synodality. Genuine joint movement is possible from the moment in which I find my place within a body that, conscious of its flagrant imperfection, yet strives to be made perfect, confident that God’s grace does indeed carry and that, to it, nothing is impossible.

Genie

In a brisk piece, Nicola Shulman reflects on ‘the overcompensating sense of self-importance that flourishes in the dark of self-doubt’, a sense likely to erupt ‘with all the towering egotism and sweet relief that a genie might feel after a thousand years in a small brass receptacle’ when some perceived slight rubs the lamp.

It is useful, then, to pay due attention to the surging of pride within us.

It may potentially point the way towards a wound that needs anointing and could be healed, if we’d let it be.

By intercepting the genie we might also, quite simply, prevent ourselves from being silly.

St Teresa

Teresa is a witness to the beautiful dimension of faith. When she speaks of it, she is categorical: ‘The fact of seeing Christ left an impression of his exceeding beauty etched on my soul to this day: once was enough’. This beauty is disturbing, even dangerous. To behold it is to be struck down. It is to walk thenceforth, like Jacob out of Jabbok, with a limp. Teresa illustrates what this means when she speaks of her transverberation, when her heart was pierced by an angel with a fiery lance. The moment has acquired emblematic force in the mystical and aesthetic canons of the West. Bernini’s marble account of it still both enchants and shocks, yet is, for all its formal perfection, but an outsider’s limited view. Teresa stresses the exquisite beauty of the angel, an emissary sent from before the burning holiness of God. The impact on her of this beautiful encounter is complex. So physical was the transfixing that her innards seemed to be drawn out when the lance retreated. So spiritual was it that it left her ‘completely afire with a great love of God’. She makes no apology for not defining the ratio of embodied and transcendent experience. Paradox alone can convey what she went through, as she sums up: ‘It is not bodily pain, but spiritual, though the body has a share in it – indeed, a great share.’ Small wonder that for days she was left as in a stupor. From a talk given ten years ago at the Brompton Oratory.

Lysfylt lampe

Dilexi te

One thing that strikes me on a first reading of Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation Dilexi te, issued today, is its section on monastic life. In an inspired reading of the Rule of St Benedict, the Holy Father says that the monks of Antiquity enabled the formation of a ‘pedagogy of inclusion’ by ‘forming consciences and transmitting wisdom’ through a sharing of culture. The word ‘inclusion’ is bandied about a lot these days, often without a clear idea of what anyone’s proposing to include others in. The notion that inclusion is a form of hospitality born of a community covenant with a view to producing a transformed society is valuable, constructive.

Acquiring an Eye

‘Chaste seeing can be re-learned. A simple, unmingled eye can be re-acquired. St Bruno assured his friend Raoul of this during his life’s last decade. Settled in Calabria, he explained the nature of the Carthusian call: «What benefit and divine gladness the desert’s solitude and silence reserve for those who love it, only those who have experienced it can know. Here, the strong can enter into themselves and remain there, with themselves, as much as they like, diligently cultivating seeds of virtue and eating happily the fruits of paradise. Here, they can acquire the eye whose serene gaze wounds the Bridegroom with love. Such an eye, being pure and uncontaminated, allows them to see God.» […] The wound which a chaste eye inflicts does not humiliate or hurt. It is sweet, like the infant’s gaze. It cuts us to the quick but feels like a blessing, reminding us of what sight can be like. To see in this manner is to re-enter paradise, says Bruno. It is part of the process of exchanging the garment of skin for the robe of glory. Sight born of love can become an act of love.’ From Chastity.

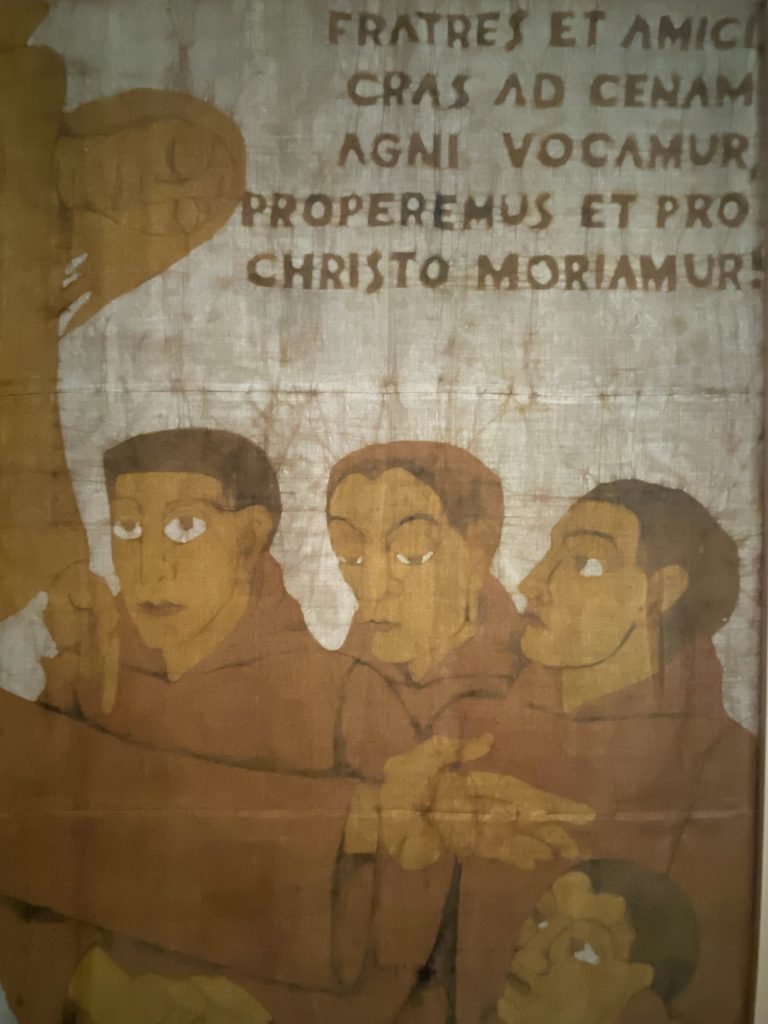

A Venetian in Buda

Walking into the refectory of the Benedictine community of Saint Sabina in Budapest this afternoon, I was struck by the large mural on the wall that shows St Gerard Sagredo, the Venetian monk who became the first bishop of Csanád, addressing his brethren on the eve of his death: ‘Brothers and friends! Tomorrow we shall be called to the supper of the Lamb. Let us make haste and die for Christ!’ The story of Gerard is gripping for several reasons. It shows the European network that underpinned medieval Catholicism, at once enabling and relativising nationhood; it shows the role monasticism played in evangelisation; and it gives credible, amiable human features to an age often presented as lost in mythic mists. Gerard was consecrated a bishop the year St Olav died at Stiklestad, in 1030. He died on 24 September (so his feast is today) in 1046. The sanctoral constantly helps us to place ourselves within a long historical continuity. The way the world is developing at the moment, that is a gift to cherish, and to share.

Sammenheng

I dag morges fikk jeg feire messe i Trondenes kirke. I sin nåværende form ble den påbegynt omtrent da Saint Louis var konge i Frankrike. Kirken ble bygd nær Laugen, innsjøen hvor de første kristne her i Harstadtraktene sies å være blitt døpt i 999 av den engelske Biskop Sigurd, som fulgte Olav Tryggvasson.

Det utsøkte alterskapet over høyalteret ble til i Lübeck på 1400-tallet. Det viser Guds Mor flankert av kvinnelige slektninger, understøttet av mannlige. Ikke bare fikk dette kunstverket stå uforstyrret gjennom reformasjonen i det sekstende århundre; det er forblitt det naturlige midtpunkt i et kirkerom som siden 1530-tallet formelt har vært luthersk.

Iblant må men en tur ut i periferien for å se store linjer som lett blir uklare i kontroversenes episentre. Derved får man hjelp til å sette mangt, også seg selv, i sammenheng.

No Soppy Thinking