Sweep of the Real

In a rich, multifaceted essay prompted by the passage through Spain of a Norwegian Cistercian, Armando Pego reflects on ways to avoid a trap into which exegetes are prone to fall. He defines it as the tendency to separate as if it were a matter of two incompatible planes literalism on the one hand from symbolism on the other; or science on the one hand from poetry on the other. Pego contends that such tidy categorisation fails to take account of reality. It fails to take in, quite simply, the full sweep of the real. The letter, he says, is part of the story; but does not exhaust it. There are points at which it must be exceeded, where mere literalism fails to do justice to things as they are. This holds for the interpretation of ancient texts. I’d say the principle can be applied no less to journalistic accounts of current events. How often are not what we are given to think of as ‘facts’ instrumentalised as tools of a blatantly partial, even willingly falsifying discourse? It is good to be helped to think about these things; to think about how we communicate and how we perceive others’ communication.

Poetry of Silence

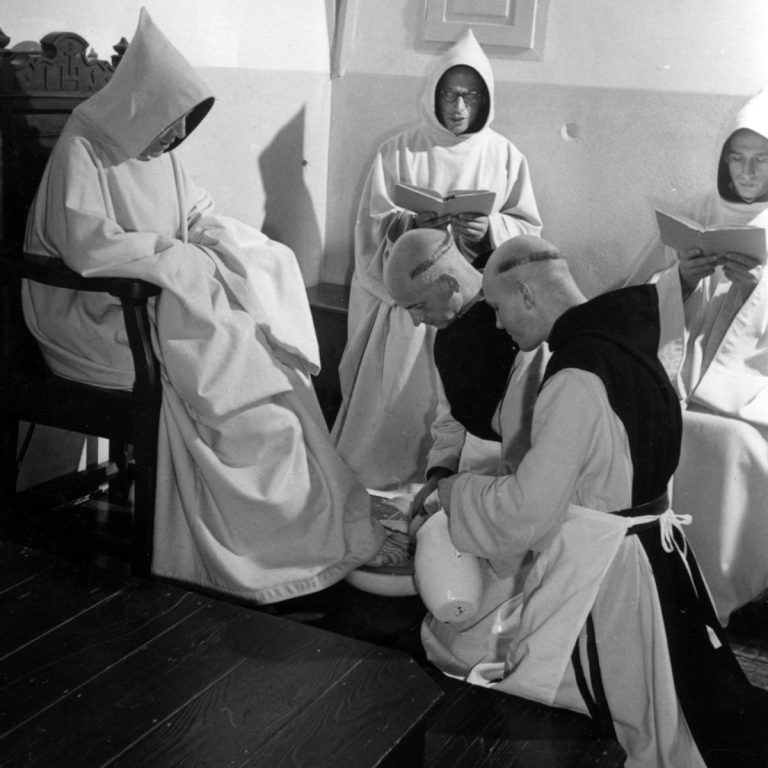

A friend has sent me a link to this documentary about the abbey of Mariawald. From one point of view the film, produced in 1959, is old-fashioned and quaint; from another it is cutting-edge. There is poetry to it. It convincingly shows that quality of contented lightness which marks authentic monastic life, though one hardly ever sees it portrayed, for people who have not themselves experienced it presume that a life of prayer and penance must perforce be grim and weighed down by self-conscious solemnity. The monk is presented here as a man profoundly engaged in the drama of this world, yet deliberately choosing and maintaining a life apart. In a rush to affirm their relevance and to seem attractive, monasteries sometimes forfeit this apartness, thinking the ancient ideal of fuga mundi outdated. This reversal rarely generates, in my experience, vitality over time. Indeed, as monks and nuns seek to revitalise their charism and call, a portrait like that of this short film gives food for thought. It has a romantic aspect, yes; but is nonetheless fully matter-of-fact, a simple reminder that a vow to give all requires a giving all in fact.

To Be a Human Being

John Bridcut’s portrait of Janet Baker is not just an account of a distinguished life; it is a distillation of humanity. Baker speaks of the death of her brother when she was still a child, a shattering event from which she was excluded by parental solicitude. ‘It was food in a terrible way for the kind of sensitivity I have needed in my working life, a tremendous gift to me from him.’ This early experience, she thinks, sealed her vocation as an artist, equipping her for a paradoxical ministry of consolation: on account of it, ‘somewhere in my voice there is this capacity to reach out to this place in people’, ‘this place’ being where one feels that life is just too much, that it’s impossible to carry on. To be able to re-read trauma in such a way, renouncing bitterness, testifies to exceptional maturity. The vitality that marks her art remains undiminished in old age. Baker speaks of taking the train into London now, ‘as a doddery old woman’, finding herself in a crowd of youngsters ‘at Covent Garden’, finding it ‘totally terrifying’ and ‘also totally exhilarating; they feel just like I did at 20, and I am so glad.’ ‘ It is not an easy thing’, says she before the film ends, ‘to be a singer; but it is far more difficult to be a human being.’ One cannot help feeling that, despite all, she has succeeded rather wonderfully.

Voicing War

Wilfred Owen was 25 in 1918, when he wrote in The Calls: ‘For leaning out last midnight on my sill,/I heard the sighs of men, that have no skill/To speak of their distress, no, nor the will!/A voice I know. And this time I must go.’ Having come back to Britain to be healed of Shell Shock, he felt the moral imperative to return to his comrades, to use his gift to speak the ineffable, to ‘cry [his] outcry’. The resolve cost Owen his life.

War can awaken poetic genius, enabling testimonies that pierce the carapace of indifference and insensitivity in which we clothe ourselves, for no one can endure being exposed to extreme stress, even to the thought of extreme stress, over time. Such awakening is happening in our time, at the Ukrainian front. The young poet Artur Dron writes work marked by sobriety and intensity, imbued with faith. If you are not yet familiar with his The First Letter to the Corinthians, do read it. Read it aloud.

Very Bones

The bishop Diadochos of Photiki, a small town in north-west Greece, was born about 400. He is believed to have been among a group of Epiran notables captured during a Vandal raid when he was well over 60, to be shipped off to North Africa where he eventually died. Diadochos did not spend life cozily cooped up in an ivory tower or a quiet cell. It is all the more impressive to read this testimony from his treatise On Spiritual Perfection: ‘Anyone who loves God in the depths of his heart has already been loved by God. In fact, the measure of a man’s love for God depends upon how deeply aware he is of God’s love for him. When this awareness is keen it makes whoever possesses it long to be enlightened by the divine light, and this longing is so intense that it seems to penetrate his very bones. He loses all consciousness of himself and is entirely transformed by the love of God.’

A longing so intense it seems to penetrate one’s very bones.

Heaven’s Gate

From a conversation with Bénédicte Cedergren about the consecration of the monastery church at Munkeby:

Reflecting upon the distinctiveness of the place and the historicity of the event, Bishop Varden emphasized that “in a way, there is nothing special about this monastery,” explaining that Cistercians usually seek withdrawal, rather than to be seen or heard. The very Constitutions of the order specify that the monks are called to persevere in a “life that is ordinary, obscure and laborious.”

“In that sense,” the bishop continued, “this monastery is as normal as any other. But at the same time, every abbey is heaven’s gate and, in that sense, something absolutely extraordinary.”

You can read the whole piece here, in the NCR.

Umbrellas

I have watched again Les Parapluies de Cherbourg. For all its garishness, for all its being locked in time (a production of ’64), it remains a moving, humane, and powerful film, a credible evocation of passion and vulnerability, of doubt, generosity, despair, and the possibility of new beginnings. Rich in emotions, it somehow manages not to be sentimental. Michel Legrand’s score is brilliant, of course, and has been interpreted by great divas. But it is the acting that makes the film immortal. Catherine Deneuve at 21 is extraordinary in the role of Geneviève. Having seen her in this film one takes for granted the stellar career that was to follow. Anne Vernon, 100 last week, is likewise impressive as Geneviève’s mother. When her daughter is tempted by self-hatred during an unwanted pregnancy, she penetrates as a matter of course the morass of her own conflicting emotions and declares with authority and conviction: ‘A pregnant woman is always beautiful’, a statement full of self-evidence we nonetheless need to hear.

They don’t make ’em like that anymore.

Religious Life

Zena Hitz’s book is presented as a philosopher’s view of religious life. What does that mean? Hitz is a learned woman. She has mastered the canon of philosophical writings; she refers to Plato and Husserl with easy familiarity, as if they were squash partners with whom she lunches. The point of the book, though, is not to shower the reader with quotations or technical terms. Hitz shows herself a philosopher chiefly in the sense that she asks “Why?” about things we take for granted. She states that her intention is not “to do justice to the enormous variety of religious communities and their influence on Christian life”—to analyze, say, the Neoplatonist strain in the Cappadocians, the mendicants’ part in rehabilitating Aristotle, or the Benedictine response to the French Revolution. This is a book designed not to flaunt learning, but to seek understanding: “I am a philosopher, and my gross ignorance, like the ignorance of Socrates, provides opportunities.” The approach works. It is refreshing, given that literature on religious life is often weighed down by ponderous self-affirmation.

From my review of A Philosopher Looks at the Religious Life in the latest issue of First Things.

Opposites

I love the passage from Sirach in today’s Office of Readings: ‘All things go in pairs, by opposites, and he has made nothing defective; the one consolidates the excellence of the other’ (42.25f.). We are offered a hermeneutic for inhabiting the world. We also get a much-needed key to self-understanding. It involves an acceptance of tension. On the one hand, I am asked to believe I have been given all I need to reach a personal, unique perfection. On the other hand, I am told I cannot reach this perfection alone. It will come to me through relationships with others, my ‘opposites’, whose differences are not in principle a threat, but a contrast needed to reveal my possibilities and potential. This perspective offers a serenely helpful corrective to an assumption present in much contemporary, secular discourse, which takes it for granted that I am defective and must repair this perceived deficiency self-sufficiently. Taken to extremes, it is an outlook that generates terrible solitude. The Biblical way of seeing meanwhile draws me into encounters and discoveries, into grateful communion.

Seminal

In a review published in La Lectura, the literary supplement of El Mundo, on 5 January Daniel Capó writes of Chastity: ‘It is, undoubtedly, one of the year’s seminal books and should be recognised as such.’ He goes on: ‘Chastity looks toward the horizon of a naturalness lived integrally, of a man reconciled with his senses, his personality ordered according to his deepest inclinations: not towards evil or selfishness, but towards a greatness that manifests in the form of service. ‘This hope,’ we read, ‘is illumined by a flicker of ontological remembrance. We perceive it in both body and mind, variously with delight and with pain, as a yearning for infinity.’ It seems no one escapes the thirst for the infinite that comes to us as a memory of a prior love. Precisely because we were first loved and knew the sweetness of that love, we are also capable of loving. This seems to me an anthropological truth. And Erik Varden explores it in his essay with unusual vigour.’

You can read the full text here.

Enter Other Lives

Reading Emily Kopley’s essay – a cracking piece of writing – on the new five-volume edition of Virginia Woolf’s diaries, I am moved by a particular entry she cites. It is from August 1937, shortly after Virginia’s nephew Julian Bell, an ambulance driver in the Spanish Civil War, had died when his vehicle was bombed in Fuencarral. He was 29. The entry reads: ‘A curiously physical sense; as if one had been living in another body, which is removed, & all that living is ended. As usual, the remedy is to enter other lives.’ Remarkable is not only the testimony to familiar closeness, showing that a statement such as ‘his life is mine’ can be verified experientially, but even more the indication of a remedy for grief. Sorrow tends to make us retreat into ourselves. No!, says Woolf. Instead it must open us up, extending our compassion. For her this process took place primarily in the realm of the imagination. The tragic end of her life shows that she was not able to live up to her counsel. That, however, does not invalidate it.

Christ’s Baptism

‘By his descent into the River, Christ marries a world of promise to one of reality, transposing the future tense of prophecy into the present. He is conscious of his passage through the waters as ‘fulfilment’ (Mt 3:15), and so is the Baptist, himself a bridge (on one bank the greatest, on the other, the least), who testifies to the horizontal, historical axis of the event. Christ utters no word, makes no gesture, and the action he performs is not in itself extraordinary. He follows a throng of anonymous others. But while they drown individual loads of guilt in the Jordan by intention, he carries the totality of sin in his body and for real (cf. John 1:29). The categorical ‘in him’ that underpins the Christology of the Pauline corpus with locative force becomes effective here, on the threshold of God’s Israel, as Christ enters fully, freely into his mission. The crossing happens secretly, but silence is broken when the Father’s voice erupts in jubilant approbation. It establishes a vertical axis of praise— praise that, in this instance, resounds from heaven to earth. It reminds us that Christ’s offering is directed, not towards a faceless Transcendence but to a Father who receives it thankfully and seals the exchange by sending the Spirit in the form that once flew forth from Noah’s hand, hovering upon the waters, unable to find rest for its feet in a drowned and stricken world, yet now coming to ‘abide’ (Jn 1:33) on the first fruit of a new creation.’ From an essay on liturgy.

About the Soul

No one has done more than Tiina Nunnally to enable the rediscovery of Sigrid Undset in the English-speaking world, revealing her as an acutely modern writer, not a producer of mock-medieval mush. Nunnally’s awaited translation of the great cycle about Olav Audunssøn is now complete. In the Christmas issue of the TLS, Hal Jensen writes: ‘Undset takes us right into the minds of Olav and Ingunn, giving voice to their thoughts, matching the big themes of sin, forgiveness, repentance and duty with the subtlety of her understanding of the psychology by which humans attempt to wriggle out of their uncomfortable moral predicaments. Sin is not a crude slogan here, it is a thing of slithering and wavering, delusion and self-deception, well-meant promises to self and self-defensive rationalizations. Undset records these internal trials with the same clear and non-judgemental eye that she brings to natural history. Although there is a strong religious element to the setting, she never climbs to the pulpit. Nor does she reach for any waffly rhetoric of transcendence. There is, however, a cumulative and mesmeric immensity to her focus. This is how to write about the soul.’

Theotokos

Each new calendar year begins with the twin feasts of the Theotokos on 1 January and of Sts Basil and Gregory on the 2nd. They carry especial significance this year. Everyone now has pet theories about the various crises of the Church. As far as I can see, there is only really one big crisis: the gradual eclipse of a true understanding of who Jesus Christ is. Catholics recognise that Jesus intervened with singular force of presence in history, but more and more fail to see him – such is my perception – as Lord of history, as the divine Logos or Reason by which (and by which only) things and destinies reveal their meaning. Once this sense is lost, all sorts of compromises begin to seem not only appealing but necessary with regard to one’s conduct and with regard to one’s understanding and proclamation of the faith. Basil and Gregory brought forward the Athanasian legacy which upheld the doctrine of Christ’s divinity, ignored and laughed at in a world, and Church, that ‘groaned to find itself Arian‘. Is a similar groan, uttered with ennui, not perceptible in our time? The determination of Basil and Gregory prepared and made possible the definition, at Ephesus in 431, of Mary as truly ‘Mother of God‘. It remains a touchstone of Catholic faith. We are called, indeed obliged, to test all our thoughts, actions, sentiments, and procedures by it.

New Year

Hungarian Shattering

‘‘The peace of heaven’, wrote Abbot de Rancé in one of his letters to the Duchess of Guise, ‘is only for those who will have preserved it on earth.’ To preserve peace, I must find it, not as an abstract ideal, but as historical reality. I must seek reconciliation with my past. I must never forget my redemption. I must learn to be grateful, then strive to live a life that is worthy of the freedom won for me. In this way, even memories of time spent in the cruellest captivity can become a source of peace, erupting in praise.’

From The Shattering of Loneliness, which this week was published in Hungarian, by L’Harmattan.

Happy Christmas!

Coram Fratribus will take a little break during the Octave.

Thank you for your interest in the site, and for your encouragement.

To accompany you through these luminous days, here is Leontyne Price singing Vom Himmel hoch with the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Karajan. If you want something to read, how about Selma Lagerlöf’s The Christmas Rose? If you go here, you can either read it yourself or have it read to you.

Today’s collect: ‘O God, who wonderfully created the dignity of human nature and still more wonderfully restored it, grant, we pray, that we may share in the divinity of Christ, who humbled himself to share in our humanity.’ Here is the decisive paradigm we need for life and thought.

Happy Christmas!

+fr Erik Varden

In medio Ecclesiae

At a time of polarisation in society, and in the Church, it is good to take up position squarely in medio Ecclesiae armed with supernatural faith. One finds this position embodied in Mère Cécile Bruyère, first abbess of Sainte Cécile de Solesmes. On 18 May 1885 she told Mère Aldegonde Cordonnier: ‘Ruins are our only building material.’ Five years later she developed this image in a letter to Dom Albert L’Huillier: ‘If you knew how clearly I can see that God founds nothing, builds nothing except with ruins, impossibilities, paralyses. It is like a mysterious game played by eternal Wisdom on the earth’s orb. I exhort you to pour all your worries, anxieties, and prognostics into the lap of God. After all, we risk nothing, we who have not to eternalise ourselves here below. Success and victory are won for us, and cannot be taken away. Let us believe that all will likewise be well for the Church we love.’ She was fond of saying: ‘We must live our Creed; that’s what gives strength for everything.’

Blessing

The question of what is and isn’t a blessing, what can and cannot be blessed, has always exercised theologians.

A helpful, careful reading of today’s declaration from the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, Fiducia supplicans, can be found in Luke Coppen’s analysis for The Pillar. Among the insights of the piece is one gleaned from a footnote, often a fruitful source of reflection, that at least implicitly frames the pronouncement. It is a text drawn from a homily by Benedict XVI for the Solemnity of the Mother of God in 2012: ‘Like Mary, the Church is the mediator of God’s blessing for the world: she receives it in receiving Jesus and she transmits it in bearing Jesus. He is the mercy and the peace that the world, of itself, cannot give, and which it needs always, at least as much as bread.’ Let us, then, invoke that mercy upon the Church and on the world, living in a way that makes us fit to receive the supersubstantial bread that alone can transform our lives. O Adonai! Veni ad redimendum nos in brachio extento.

Art of Life

It is a high form of charity to recognise in others qualities they’d no idea they had, to see a potential they might not have expected, thereby giving them courage to keep trying, to grow and blossom.

Someone able to see in this way is Ana Zarzalejos Vicens, whose profound and witty essay ‘Beer and Chastity: The Art of Living‘ appeared yesterday, filling me with gratitude.

She sums up something I said in Madrid in the following phrase: ‘If you’re going to play the great game of humanity, don’t let anyone downplay its significance for you!’

I stand by that message, glad to hear it resonate.

Opening Doors

‘The word of salvation does not go looking for untouched, clean and safe places. Instead, it enters the complex and obscure places in our lives. Now, as then, God wants to visit the very places we think he will never go. Yet how often we are the ones who close the door, preferring to keep our confusion, our dark side and our duplicity hidden. We keep it locked up within, approaching the Lord with some rote prayers, wary lest his truth stir our hearts. And this is concealed hypocrisy.’

From Custodians of Wonder: Daily Pope Francis, a florilegium just published by Silentium.

You can read the book’s preface here.

Dead Leaves

For the sixth year running, Finland is top of the UN’s Happiness Report. Talking to happiness-hungry foreigners, Finns will tend to nuance the nomination. How do they address the question among themselves? Go and see Aki Kaurismäki’s film Fallen Leaves. I did this week. I loved it. I wasn’t the only one. At the end, the audience clapped. The setting is contemporary. At regular intervals, people switch on the radio. The talk is unfailingly of Russian atrocities in Ukraine. Finland shares a boundary with Russia that is 1340 km long. One is reminded of the precariousness of things. Interiors and costumes might as well be from the 70s. Technical advances, we are left to surmise, do not change deep sensibilities. Authority is largely presented as callous. There is no idealisation of structures. Finns aren’t happy just because their country works well. Kaurismäki points to the source of wellbeing in the tenderness with which he portrays individuals, their vulnerabilities, foibles, and mad hopes. There are moments of great beauty. Also, the film is brimming with liberating self-irony. The point is not trivial. I find it to be a rule that the happiest people I know are are the ones best able to laugh at themselves.

Books of the Year

It’s the season of book supplements.

Chastity made it onto George Weigel’s list compiled for First Things. He writes: ‘In Chastity, Bishop Varden explains just why that much-misunderstood virtue is a matter of living what John Paul II called ‘the integrity of love.”

In The Tablet, Dom Luke Bell writes: ‘With an extraordinary sensitivity to the meaning of words in languages ancient and modern, Erik Varden’s Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses is a brave and timely book which restores the full resonance of the virtue of chastity. Grounding his reflection in the ancient Syriac text The Cave of Treasures, he finds it to be about seeing with unclouded gaze, “attentively and reverently”. With culture and humour, he leads us to the sublimity of the beatific vision.’

Liturgy

Today marks the 60th anniversary of Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Second Vatican Council’s constitution on the sacred liturgy, a document worth re-reading from time to time.

For me, the most essential part of Sacrosanctum Concilium is this: ‘Christ Jesus, high priest of the new and eternal covenant, taking human nature, introduced into this earthly exile that hymn which is sung throughout all ages in the halls of heaven. He joins the entire community of mankind to Himself, associating it with His own singing of this canticle of divine praise’ (n. 83). It is a wonderful, endlessly fascinating statement. By means of it the Second Vatican Council reminded us that liturgical worship is essentially mystic incorporation — through Christ, with him, and in him — into the ineffable communion of the Blessed Trinity. This theological dimension must ever remain a criterion for liturgical practice, even more for liturgical change. It reminds us that the liturgy is not a human project; it is a work of divine transformation, a novitiate for eternity.

St Andrew

‘Modern psychology has taught us much about sibling rivalry, believed to be among the primary relations that form a life, with the potential to really mess it up. Research gleaned from the analyst’s couch is corroborated by Scripture. Think of Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau, Leah and Rachel. What twistedness, what pain, we see in these pairs of brothers and sisters! It is interesting, then, that in recruiting for the apostolic college, seeking heads for the Twelve Tribes of the New Israel, Christ should have wished a high percentage – one-third – to be blood brothers. If Christ assumed these complications into his closest band of followers, it was perhaps to show that natural limitations, relational conditioning, can be overcome if we truly become disciples. James and John, Peter and Andrew, grow in faith and stature through the Gospel account, to the extent that, after Christ’s rising, they are ready to be sent, each with his itinerary, to the ends of the earth, to proclaim life’s victory. They’ve grown up. They’ve left themselves behind. Thus they’re freed for mission.’ From Entering the Twofold Mystery.