Shielding Yourself

‘What photography does is to make you bold beyond your normal powers, it’s a way of shielding yourself.’ Ian Jeffrey makes this statement about Dorothy Bohm in Richard Shaw’s documentary Seeing Daylight. The film is a moving account of the great photographer’s life, a remarkable testimony to a way of seeing that is at once acute, illusionless and compassionate. Jeffrey again: ‘For a short period during the 40s and 50s tenderness dominated photography’. Dorothy, he remarks, ‘lived in that particular world’. She somehow managed to keep it alive. Her photography is marked by philanthropy. She grew up amid trauma. She was conscious of the advances achieved during her lifetime. Yet, as a Financial Times tribute observed: ‘Bohm’s greatest wish, in a world where billions of images are carelessly created every single day, is more poetic than political: slow down and take the time to really see the world around you, she says. Look through your eyes, rather than your phone.’

Choreography

We are culturally conditioned to think of discipline or rules as standing in contrast to spontaneity and freedom. The perception is mistaken as a matter of principle. I’ve recently reread a great essay by Lord Sacks that touches on this subject. Speaking of the resilience of Israel’s faith, he reflects that ‘love remains strong after 33 centuries. That is a long time for love to last, and we believe it will do so forever.’ Then he asks: ‘Could it have done so without the rituals, the 613 commands, that fill our days with reminders of God’s presence? I think not. Whenever Jews abandoned the life of the commands, within a few generations they lost their identity. Without the rituals, eventually love dies. With them, the glowing embers remain, and still have the power to burst into flame. Not every day in a long and happy marriage feels like a wedding, but even love grown old will still be strong, if the choreography of fond devotion, the ritual courtesies and kindnesses, are sustained.’ It is helpful for Catholics to apply this insight to themselves, to the rich tradition handed on to us.

Light from Light

Today the sun was seen for the last time this year in Tromsø. It will not be visible again until after 14 January. To look forward to Christmas in such a climate is singularly meaningful. The great themes of the liturgy – ‘and in that day there will be a great light’ – speak with urgency; and we are challenged to face with courage the darkness in our own hearts, our constitutional need for illumination. For no amount of Vitamin D can make up for the absence over time of the Light from Light. In the words of a lovely seasonal hymn composed up here in the north, we sing: ‘This is for us the hardest turn/we struggle to drag ourselves forwards/towards light and Advent/Bethlehem seems a long way away.’ It can, though, be brought electrifyingly close. What is it to ‘love the light’, to choose to come to it (cf. John 3)? Long winter nights make the stakes come alive.

The Crucified’s Victory

Christians of the Middle Ages saw in Nicodemus one who had pierced the mystery of the Passion. A tradition arose that attributed works of art, moving representations of the Crucified, to Nicodemus. He was considered the creator of both the Holy Face of Lucca and the Batlló Crucifix. It is significant that our forbears found him apt to be a sculptor, master of a tactile art, forming what he had seen with his eyes, touched with his hands. Without needing to debate the veracity of such ascription, we can recognise in it perennial symbolic validity. Nicodemus is an example for us who strive synodally to be true disciples and seekers after holiness. Why? He stays away from facile polemics and theatrical gestures. Still he follows the Lord wherever he goes. When he is needed he offers his service and volunteers his friendship to the community. He shows us what it means to be faithful in the darkness of Good Friday. Contemplating the crucified, entombed Christ, he had wisdom to recognise in desolation something sublime, a glorious, divine revelation. Thus he became an authoritative witness to the Crucified’s victory. Truly, this is an attitude the Church needs now.

From Synodality and Holiness, now available also in French, Italian, and Polish

Pauline Matarasso RIP

In my view, the best book on the Cistercian patrimony, alongside Bouyer’s Cistercian Heritage, is Pauline Matarasso’s The Cistercian World. Pauline, a woman of formidable culture, had an understanding of the monastic life that was at once intellectual and connatural. Introducing the third abbot of Cîteaux, she observed: ‘All that Stephen Harding touched bears witness to his pursuit of authenticity, of the spirit that only the authentic letter can set free.’ It is a brilliant insight. She was well placed to produce it. Spirited pursuit of the authentic letter defined her distinguished career as a translator (of medieval epics, of Bobin and Noël), historian (e.g. of her revered father-in-law Isaac Matarasso), and essayist. Even as she lay dying she kept translating, committed to finding and making sense accurately and beautifully. She was one of the noblest, most gracious people I have ever known. She once wrote: ‘Whereas a tiger is born, we are made, and in most of us the making process is still incomplete when death takes us, however late.’ I’d say what had been made when death came to her last Wednesday had reached a kind of perfection. May she now know in fullness the loving truth she sought with fidelity and, unknowingly, radiated.

Leavings

This is the dying time, when earth

relinquishes its surplus.

These words once mine

blown on a cool wind

from the lost land of the mind

settled last night like quiet birds

on memory’s shore.

I greet them with surprise –

together we will journey blind,

probing the ever shifting sands,

unsure of what’s in store . . . only

that there is more.

Before a shivering silvered night

lures to a feast the spoiler frost,

be quick to pick, cost what it may,

the late fruit on your tree,

– there’ll be no more –

and leave it on the roadside stall

where the merchandise is free

to all who pay their dues in kind

for other walkers on the way

where less is more

Pauline Matarasso (1929-2023)

Consecration

Thirty years have passed since I first saw Nicolas Dipre’s Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple in the Louvre. For having been painted half a millennium ago, it is strikingly contemporary. The Virgin waves fondly, a little bashfully to her parents as she makes her way up the winding temple stairs. Anna and Joachim wave back. They’re visibly filled with pride and foreboding, trying not to show sadness at the parting. All of us can recognise this scene: the first significant departure from home, the sense of suddenly following our own path with all that it entails: responsibility, excitement, anxiety. The story of Mary’s presentation is apocryphal. That doesn’t mean it isn’t true. It shows us that a decisive Yes to God’s call, like the one the Virgin gave at the Annunciation, is prepared by innumerable hidden, unspectacular yeses. By small steps we consecrate our will, our being to a higher purpose. The temple stairs are a parable of our life. ‘One step enough for me‘. Yes. What matters is to take the one which is today’s.

Interest

This angel is a detail from a painting from about 1360 on display in the Thyssen Collection in Madrid: The Virgin of Humility with Angels. The viewer is impressed by the elegance of the ensemble. I find myself especially intrigued, though, by the representation of the angels, a subject dear to fourteenth-century artists. According to Biblical evidence, these ethereal beings are charged with a ministry of perfect worship before the face of God, yet here is a specimen contemplating a human reality, the Infant Jesus in the Virgin’s arms, with a most engaging interest. The expression on the angelic face is marked by keen curiosity. A key aspect of Christian faith is thus articulated. The incarnation of the Word does not simply restore human nature to original integrity. It realises a potential for divinisation that leaves even the seraphim astonished. The anonymous Venetian painter’s angel spurs us on to self-examination: Am I conscious of, and do I cooperate with, what God might realise, through pure grace, in my redeemed human frame?

Belshazzar

The office of readings today gives us the account of Belshazzar’s feast (Daniel 5,1-6,1), a supreme example of human presumption. Deliberately and pointedly, Belshazzar publicly profaned objects dedicated to a sacred purpose, his intention being to show himself superior to any purportedly divine institution. While his act of blasphemy was being carried out, ‘the fingers of a human hand appeared, and began to write on the plaster of the palace wall’. The message spoke of measurement, weighing, and division. It did not voice an angry judgement, simply an affirmation that Belshazzar, a ruler of men, was unworthy of the task, not up to it. That same night he was eliminated by his staff.

There is a timeless parable in this biblical story. For each of us there is stuff for self-examination. Would I, on being weighed, be found wanting, or would I correspond to the legitimate estimate? Let’s not forget that in Biblical Hebrew, ‘weight’ is correlative to ‘glory’.

Ordinary?

‘Teresa of Ávila’s Autobiography, completed in her fiftieth year, chronicles the irruption of the divine into an ordinary life. Seeing Teresa at a distance, we may object to the adjective ‘ordinary’. She seems anything but! Teresa, however, argued this point with passion. She was conscious of singular favour shown her; but she insisted that nothing in her nature marked her out from the common run of men and women. She presents her life in its extraordinariness as a typical life, an exemplar each of us might emulate, had we but faith and courage to surrender to God’s work in us. The trajectory she traces reaches from the outset right to the loftiest end of spiritual life. She counsels souls who wobble ‘like hens, with feet tied together’ but also those who soar like eagles. Nor does she forget the perplexing darkness of the long intermediate stage when the soul, like a timid dove, is dazzled by rare glimpses of God’s Sun while, ‘when looking at itself, its eyes are blinded by clay. The little dove is blind’. Everything she writes, she tells us, is born of experience. For long years she herself ‘had neither any joy in God nor pleasure in the world’. She lived in an in-between state, a no-woman’s land. What changed it?’

From a talk given in 2015.

Responsibility

It was stirring to read today’s Gospel (Luke 17.1-6) in the Carmel of the Incarnation in Ávila, St Teresa’s monastery of profession. The Lord calls us to responsibility. We are to make sure our options do not cause scandal to others. Hearing this text today, we may think chiefly of massive, public scandals, but the admonition applies no less to everyday life. Does this particular choice I make edify or break down communion? The criterion is useful in any circumstance. Jesus asks us, too, to take responsibility for others. Not to take over their lives. Each must answer for his or her freedom. But we can help each other to see clearly. ‘If your brother sins, reprove him’. We shall do this effectively if we speak the truth in love, gently holding up a mirror that reflects reality to one lost in illusion. To forgive as Jesus bids us, with endlessly renewed hope of amendment, we must pray daily, ‘Increase our faith’, a prayer embodied in the life of Saint Teresa. The courage she had to review her vocation in the light of faith, to deepen what were already good choices by better choices, then to stick to them, was a source of profound renewal for the Church in a time of decadence. Her example encourages and challenges us to do likewise.

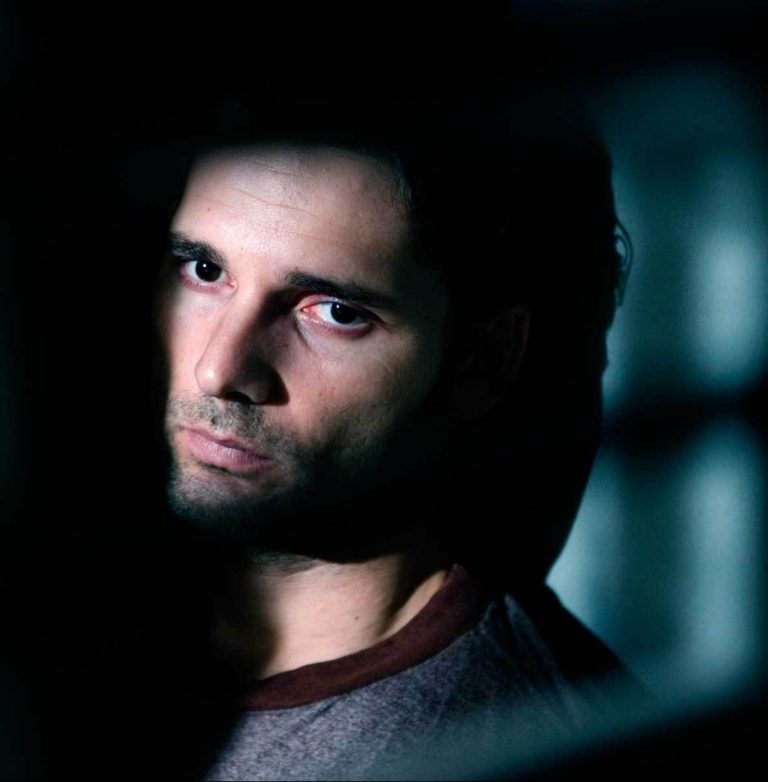

Digital Man

Among Ximo Amigo‘s paintings exhibited at the Encuentro Madrid is this one, entitled ‘Digital Man’. The formal reference is to a long painterly tradition of chiaroscuro; we might think of Georges de la Tour’s La Madeleine au Miroir. Whereas she, though, is rendered warm, present by the light that illumines her, her features accentuated, Amigo’s figure’s face is all but obliterated by the eery light issuing from his iPhone. He acquires an alien character. That is the great strength of the canvas. It represents a determined act of self-estrangement.

The picture is unsettling. One feels like passing it in a hurry. I found myself nonetheless compelled to pause before it — to let myself be challenged and examined by it. And to recognise an arresting account of a peculiarly modern experience of loneliness.

Dedication of the Lateran

‘What matters about the Lateran, the cathedral of Rome, is this: by its dedication, the mystical Church was shown, urbi & orbi, to be palpable and real. It was placed on the map. Constantine marked the Lateran out as a place of intersection. ‘Here’, he proclaimed, ‘our earthly city encounters that of heaven; here God’s kingdom impinges on ours.’ Like Jacob he discerned, in this transient world, the very house of God. When we recall his act of solemn dedication, we, too, say: God is with us! We give thanks for God’s mercy touching our lives in the Church, when we receive the sacraments, when we meet as church to worship, to serve. The Lateran, Mother of all churches, stands as a pledge of our ecclesial communion, making it visible. It is a wonderful gift! Yet it points beyond itself. That is the lesson taught us by our readings. A touch of Noli me tangere, of ‘Do not cling to me’, marks all manifestations of grace in this world.’

From a sermon for 9 November.

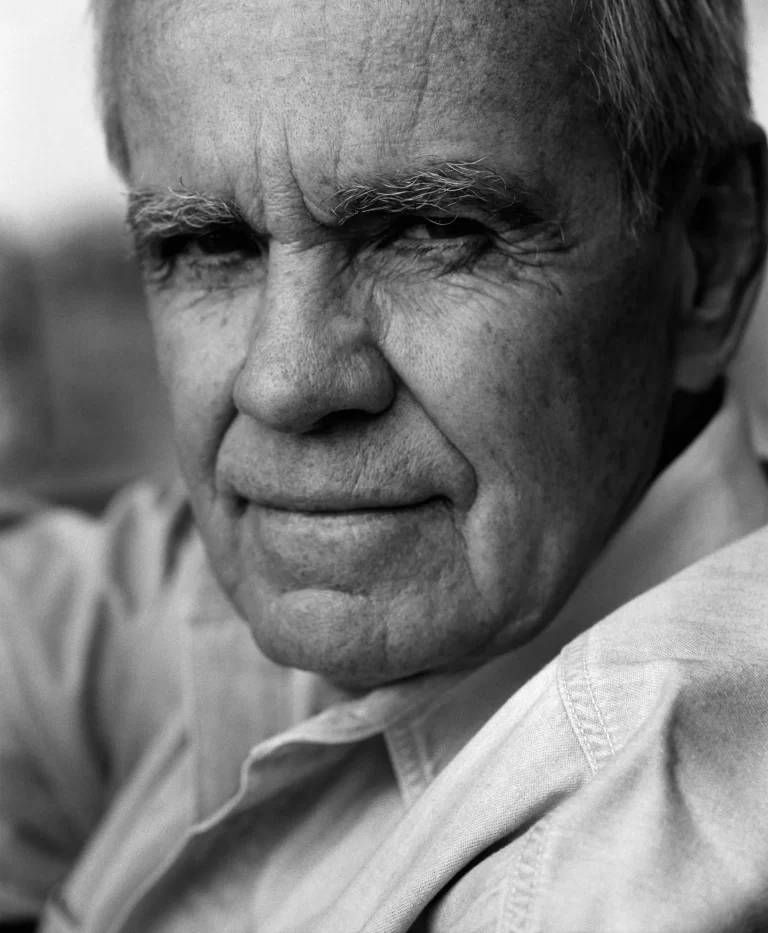

Putting up with us

Since the death of Cormac McCarthy on 13 June, tributes have been numerous. The world has lost one of its greatest, most challenging modern writers, brought up a Catholic. I have read with interest an appreciation by Valerie Stivers. It concludes with this beautiful reflection on one of McCarthy’s novels: ‘By the end of the final novel in the Border Trilogy, Cities of the Plain, the protagonist, Billy Parham, has seen much. In the final scene, a woman gives him a place to sleep. He can make little sense of his life and tells her, “I aint nothin. I dont know why you put up with me.” She responds: “Well, Mr Parham, I know who you are. And I do know why. You go to sleep now.” The Blessed Virgin Mary? Holy Mother Church? It’s foolish to try to pin McCarthy down. But it’s also foolish to ignore the invitation to rest in something, perhaps Someone, who knows us, even to the depths of our wickedness, and who puts up with us and knows why.’

House of Brede

Nuns in films these days tend to conform to two stereotypes: either they cheerfully respond to the spotlights, shedding inhibitions they never knew they had; or they embody gothic horror, subject to unimaginable captivities. There is not much verisimilitude in either extreme. I was thrilled when I discovered the other day that YouTube houses a flickering but still watchable copy of In This House of Brede, George Schaefer’s adaptation for the screen of Rumer Godden’s 1969 novel. Godden knew monastic life and understood it. Not for her saccharine or horrific caricatures. Brede, a Benedictine abbey modelled on known houses, is a place in which people learn what it really means to live, to give up illusion, not to encounter others as projections of one’s own loss or desire. ‘We had to learn’, says a key character, ‘to care less for each other and more for all the rest’, a model of the widening of the heart that engenders not estrangement but homecoming. Sr Philippa, played by Diana Rigg, speaks at the end of an ‘incredible sense of belonging – in the world’, recognition that can be a genuine fruit of contemplative living. The film is not perfect, but worth seeing.

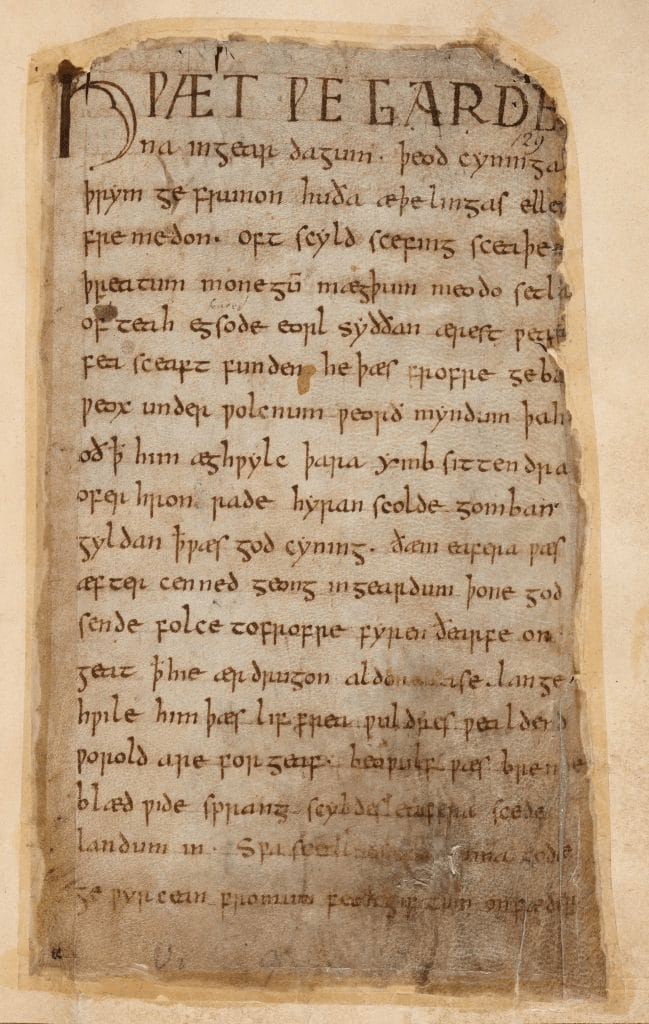

Not la-di-da

It is sometimes supposed that studying ancient literature is a pastime for la-di-da layabouts wanting to seem clever or for irremediable nerds. What nonsense. The thing about great literature (and if people have bothered to transmit certain texts for centuries, there’s a good chance there’s greatness there) is that it takes us to the heart of things, enabling us to see clearly. I am stirred by Irina Dumitrescu’s piece on Beowulf in today’s TLS. It is the clearest commentary I’ve seen on much that we’re now living through, albeit at a distance. ‘[M]anufactured nostalgia is one way to make the violence of conflict bearable’. ‘Monsters can be vanquished – the hatred fomented between neighbours abides’. ‘How easy it is to miss the grief of others’. Dumitrescu notes that translators often ease the motif of fear out of the text. Why? ‘I have no proof, but I suspect some editors needed the Danes and Geats to be heroic for their great epic. The lesson of Beowulf is not the glory of war, though, but its inevitable failure. At the poem’s end a Geatish woman sings in grief and terror. She knows what war will bring: slaughter, humiliation and captivity.’

Worry

The board of governors of the Jewish community in Oslo has issued a strong appeal: ‘It is imperative that more people use their influence to resist hate-speech of any kind. We invite all to avoid simplification and prejudice leading to greater polarisation and hatred.’ The appeal is noble, in many ways timeless; but it issues from concrete circumstances, provoked by threats and violence against Norwegian Jews. That such a thing should occur is shameful. Anyone is free to have an opinion about a political regime; entitlement to voice an opinion is fundamental to our notion of society. Though to translate antipathy towards a regime into acts of hatred against a people is not just simplification, it is idiocy. Nothing is a surer sign of cultural decadence than then fact that antisemitism again raises its ugly head. Instruments against decadence are informed insight, learning, humanity, readiness for conversation — and spiritual values. As our poet Nordahl Grieg wrote, only spirit can halt an accelerating drift towards death. We all have our part to play, indeed we are morally obliged to play it.

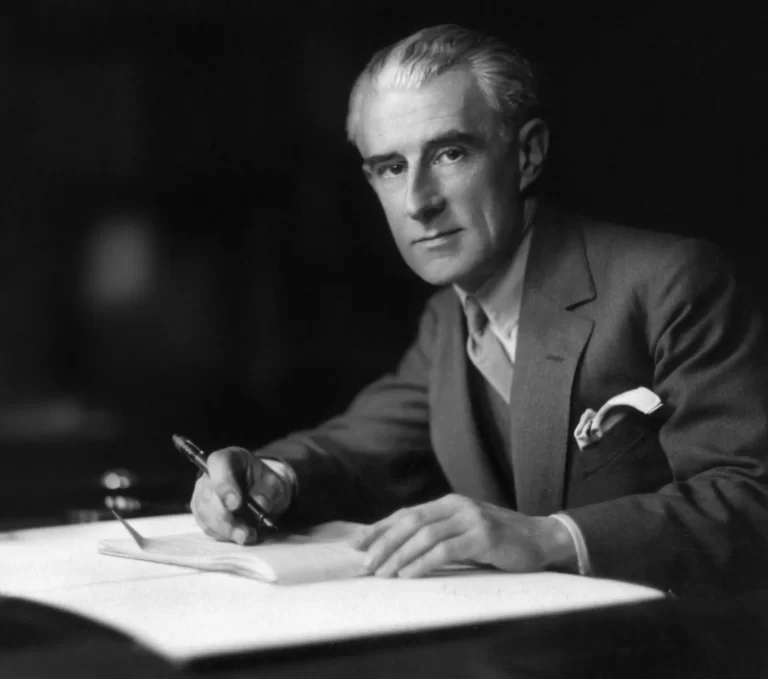

La Valse

Poulenc, at 22, was present when Ravel first performed La Valse for Diaghilev, who had commissioned it. ‘Ravel arrived very simply, with his music under his arm, and Diaghilev said to him, in that nasal voice of his: ‘Well now, my dear Ravel, how lucky we are to be hearing La Valse.’ And Ravel played La Valse with Marcelle Meyer, not very well maybe, but anyway it was Ravel’s La Valse. Now at that time I knew Diaghilev very well. I saw the false teeth begin to move, then the monocle. I saw he was embarrassed. I saw he didn’t like it and was going to say ‘No.’ When Ravel had got to the end, Diaghilev said something which I think is very true. He said ‘Ravel, it’s a masterpiece. But it’s not a ballet. It’s the painting of a ballet.’’ Nonetheless, the work has proved immortal. It has been subject to the most outlandish interpretations. This performance is terrific. Towards the end Marta Argerich, normally of such austere appearance when she plays, beams with delight.

Education

It is interesting to note what Sigrid Undset, a complex-free woman, wrote about sexual eduction in schools back in 1919.

“It goes against the modesty of children, against the modesty of any human being, even to imagine a casually gathered assembly forced to sit and listen to an exposition of sexual life. Not even the crudest presentation face to face could in reality do proportionately as much harm. It is said that this is done in order to keep sexual life from standing in a mystical light — as if it were not precisely the mystical light that distinguishes human sexual relations as specifically human; the mystique resultant upon the fact that we have dragged these relations through all available mud, and exalted them high above all the stars. This is precisely what children cannot understand: the infinite possibilities of baseness and exaltation. Only a human being possessed of the urge can understand it. For sexually indifferent natures the business will seem common, bizarre, ridiculous, and unpleasant — it cannot be otherwise for a normally developed healthy child.”

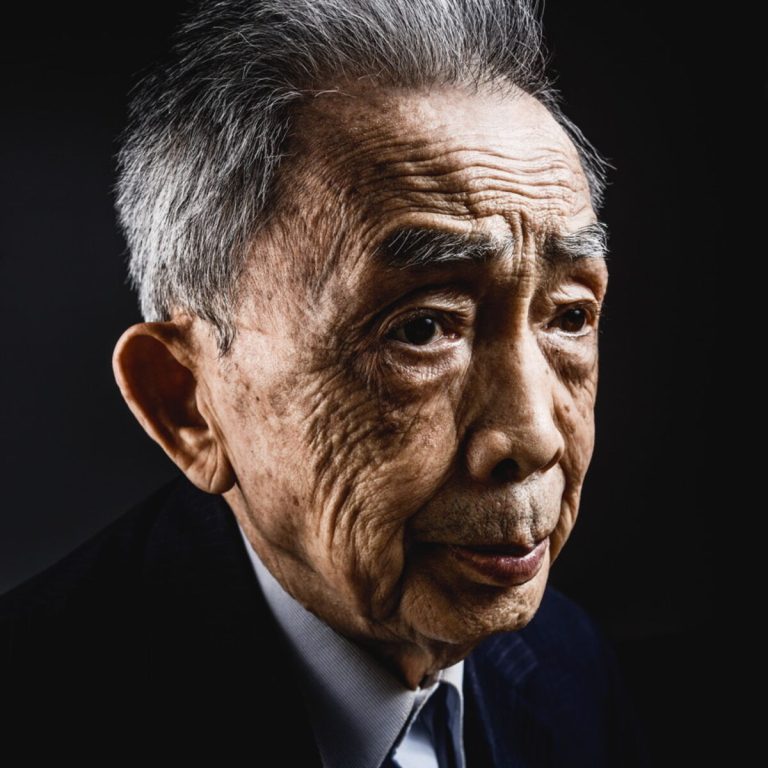

Response

In his recent autobiography, François Cheng insists he is no sage. Yet he writes wisely. He describes a nocturnal experience on a balcony in Tours, seated underneath the Milky Way: ‘I am there, in this grandiose night bursting with splendour, posed between the heavenly river and the earthly river. Compared to the incommensurable volume of the cosmos, my being is so minuscule it seems inexistent. My eye is no larger than a grape, my skull no larger than a coconut, yet I am he who has seen and known. At the heart of eternity, be it for a few seconds, all is not there for nothing, for this beauty has stirred my being. What is this inexplicable paradox? What is the design of the creative force, let us say the Creator, who brought about the cosmos and Life?’ The poet answers by means of further questions: ‘Could he have contented himself with the stars that turn indefinitely without knowing it? Would he not have needed someone to respond, beings graced with a soul, a spirit, as we are, to make sense of his Creation?’

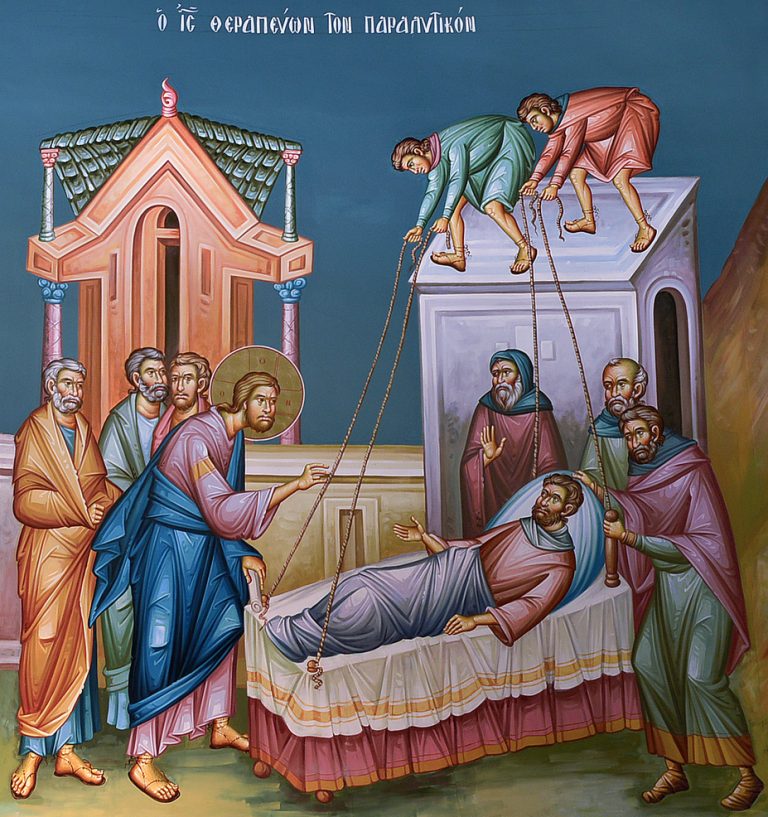

St Luke

Today we keep the feast of St Luke. He was, writes Paul (Col 4.14), a physician. A physician, like a priest, gets to know humanity well. It is his privilege to accompany people through vulnerable, sometimes anxious stages of life. A good doctor becomes a good observer. That is quality amply expressed in Luke’s Gospel. Many of the best drawn profiles in the New Testament – the prodigal son, Zacchaeus, the woman bent double – are from his pen. His influence on our culture’s imagination is immense. It followed as a matter of course that he got a reputation for being a painter. To learn to see truly, to see ourselves and other people as we are, fragile but bathed in mercy, with a tremendous ability to transcend ourselves, to be transformed by God’s power, is an essential part of the Christian condition. Today we might ask: Do I see in this way? Do I want to learn to see in this way?

Oratorio

Christian proclamation has always been pluriform. The mystery of the Divine Word exceeds what words alone can express; so art comes to the rescue – painting, music, sculpture, and architecture. A Norwegian oratorio based on the life of the apostle John was premiered in May this year. The music, ambitiously conceived, was written by Ole Karsten Sundlisæter to beautiful texts by Dordi Glærum Skuggevik. Musically speaking, I’d say the strongest parts are the most lyrical, like Mary’s account of the resurrection (‘31.10) or the dialogue between Jesus and John that follows John’s question, ‘Are you Lion or Lamb?’ (‘52.58). The sword that pierced Mary’s heart is powerfully, maternally evoked: ‘I understand so little! Your paths recede into death and the night, into darkness and the thicket. I gave you my ‘Yes’, but not to this!’ The Light shines in the darkness, to transform it. The message from John’s Gospel here finds an articulate, contemporary voice.

John XXIII

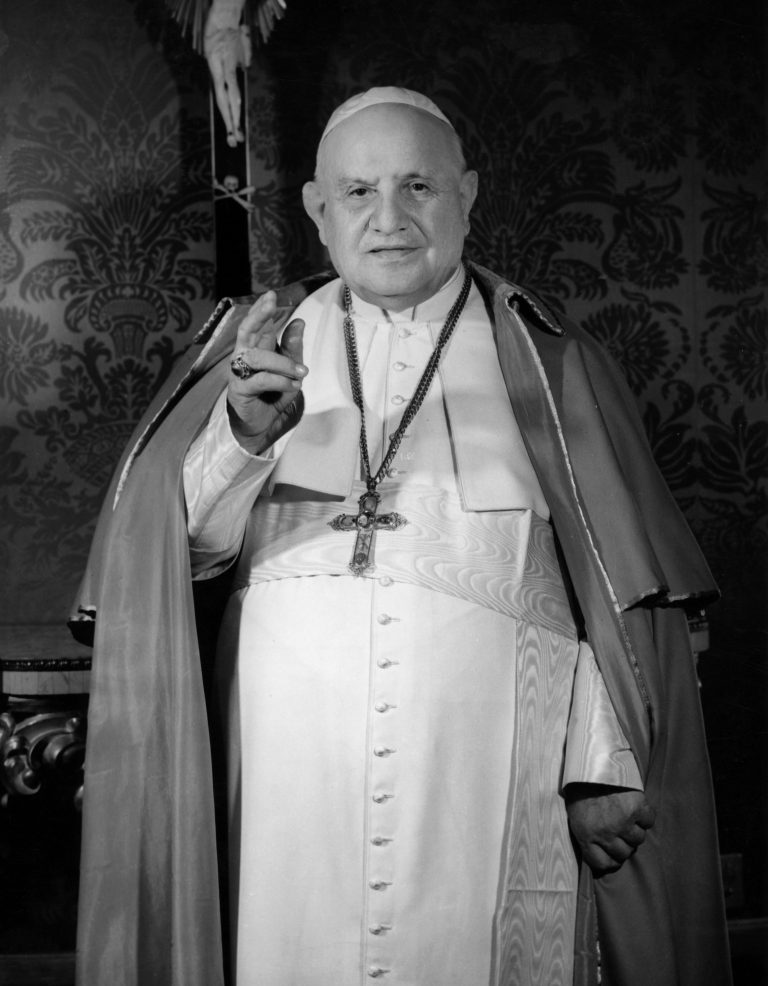

The name of John XXIII, that beloved pope, is often invoked a little reductively. We like to think of him as a rotund, friendly old fellow who cracked jokes and opened windows. These associations are not untrue; but they are incomplete. There’s an austere aspect to Pope John’s magisterium we should not forget. I find it helpful now to re-read his encyclical Paenitentiam agere dated 1 July 1962, in view of the opening of Vatican II. By this letter, he asked all Catholics around the world to help prepare the council — how? By doing penance. ‘Doing penance for one’s sins is a first step towards obtaining forgiveness and winning eternal salvation.’ Leading mankind to salvation is what the Church is about. An Ecumenical Council, ‘a meeting of the successors of the Apostles, men to whom the Saviour of the human race gave the command to teach all nations and urge them to observe all His commandments’, must be preceded by a global examination of conscience and concrete signs of repentance, like those adopted by the Ninivites at Jonah’s preaching. The ‘manifest task’ of the Council, wrote John XXIII would be ‘publicly to reaffirm God’s rights over mankind, whom Christ’s blood has redeemed, and to reaffirm the duties of redeemed mankind towards its God and Saviour.’ Have we today that same priority, or are we more concerned with what we perceive as God‘s ‘duties’ towards us?

Home

News from the Middle East is so awful, opening such dreadful vistas, that I am left numbed. Hamas’s terrorist attack, its hostage-taking are inexcusable; at the same time Israel’s political course prompted a BBC journalist to ask a pundit yesterday, ‘Could Israel not see this coming?’ I keep thinking of a sequence from Spielberg’s Munich from 2005. Avner Kaufman’s Mossad unit, working secretly, winds up in Athens sharing let accommodation with a Palestinian group. Tension is high, yet there is the possibility of encounter at a human level. There’s a wonderful scene with a radio. Out in the hallway, the leaders of each unit talk – really talk, with a flicker of understanding. They could be brothers. A door could be opening. At the end of the exchange, one says, as if speaking for both, ‘Home is everything’. The following day they are fighting each other to the death. There is a parable in this. Unravelling now in the Holy Land is the curse of Lamech, ‘If Cain is avenged sevenfold, truly Lamech seventy-sevenfold’ (Genesis 4.24): a spiral of vengeance with no end. Men must choose to end it, led by the voice of God, one of whose Biblical names can be read to mean, ‘He who says: Enough!’

Fosse

On a visit to Lisbon in Eastertide this year, I was touched to see the poster on the right. There he was, Jon Fosse, whose voice seems to me so quintessentially Norwegian I wouldn’t know how to begin to translate him, quite as a matter of course, seemingly at ease, on a billboard in Portugal, unselfconsciously cosmopolitan. Reading the press this week, I’ve been struck by the repeated stress on the universal aspect of Fosse’s work. He is, of course, deeply rooted in a global culture. It is wonderful to have a distinguished poet who is himself a translator, used to grappling with sense, noting that his version of Kafka’s The Trial aspires to the utmost accuracy, ‘each and every word’ having been weighed, who can say about the Greek playwrights, ‘they have very distinct voices, Aeschylus, Euripides, and Sophocles. It’s very easy for me to hear and to write that voice in the way I write, in my language, in this time’. The universal in the particular, the particular in the universal: a perennial give-and-take that can be a cliché, but which in cases like this Nobel Laureate’s is electrifying because the creative act of writing is such a serious, essential business for him. Wisdom is born thereby, and beauty, a song like no other song.