Subversion

Professor Ritchie Robertson recently wrote about Willa and Edwin Muir: ‘The religion with which the Muirs were most familiar was Scottish Calvinism, and they roundly rejected it. Edwin tells in his autobiography of seeing, in a Glasgow slum street, a young man repeatedly hitting another for no apparent reason. To remonstrances, the aggressor replied, “I ken he hasna hurt me, but I’m gaun tae hurt him!”. In retrospect at least, Muir found this an image of Calvin’s predestination: God has decided before the beginning of the world who will be saved and who damned, and mercilessly inflicts a punishment which its victims have done nothing to deserve. Muir explored Calvinism further in his hostile biography of John Knox (1929) and in a remarkable essay, “Bolshevism and Calvinism” (1934). The Calvinist and Bolshevist elect, he argues, both consider themselves saved and anticipate with satisfaction the damnation or extinction of sinners and bourgeois.’ The aptitude human beings have for institutionalising, then rationalising their subversion of high ideals is fascinating and redoubtable.

Subversion

I keep thinking of something Professor Ritchie Robertson recently wrote about Willa and Edwin Muir: ‘The religion with which the Muirs were most familiar was Scottish Calvinism, and they roundly rejected it. Edwin tells in his autobiography of seeing, in a Glasgow slum street, a young man repeatedly hitting another for no apparent reason. To remonstrances, the aggressor replied, “I ken he hasna hurt me, but I’m gaun tae hurt him!”. In retrospect at least, Muir found this an image of Calvin’s predestination: God has decided before the beginning of the world who will be saved and who damned, and mercilessly inflicts a punishment which its victims have done nothing to deserve. Muir explored Calvinism further in his hostile biography of John Knox (1929) and in a remarkable essay, “Bolshevism and Calvinism” (1934). The Calvinist and Bolshevist elect, he argues, both consider themselves saved and anticipate with satisfaction the damnation or extinction of sinners and bourgeois.’ The aptitude human beings have for institutionalising, then rationalising their subversion of high ideals is fascinating and redoubtable.

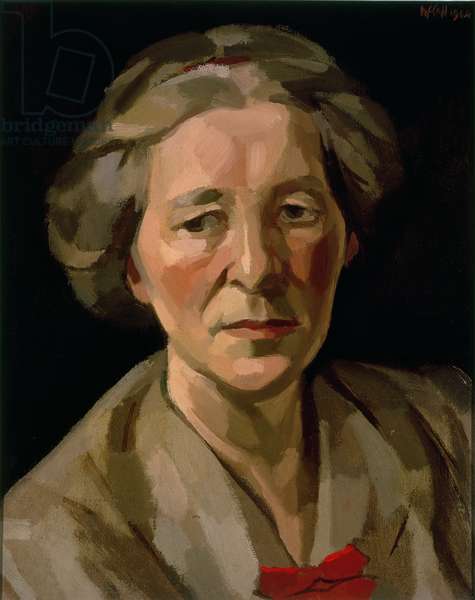

Lejeune

Is there any person in recent times who strikes you as embodying the full meaning of chastity?

For the full meaning of chastity we must look towards the Word made flesh. But yes, I can think of individuals who incarnate this quality in signal ways. The first who comes to mind is Jérôme Lejeune, the discoverer of Trisomy 21, a husband and father. I have read some of Lejeune’s letters to his Danish wife Birthe, which reveal the depth of their relationship, marked by deep affection and respect; but I also think he represents chastity more broadly, in his way of dealing with patients (in a marvellous documentary you can hear the mother of a child with Downs say something like, ‘Seeing Dr Lejeune hold my son taught me to receive him as my child, not a problem’) and in the moral courage with which, to stay true to his convictions, he relinquished his career.

Synodos

It is endlessly fascinating to see how the word of Scripture illuminates specific situations in unexpected ways. Today’s Mass readings follow a cycle established decades ago; they are not specifically intended for the first retreat day of the Church’s synod; yet their message to this assembly called to ‘walk together’ in the Spirit is inspiring. The Church is challenged: ‘You say, ‘The way of the Lord is not just.’ Hear now, O house of Israel: Is my way not just? Is it not your ways that are not just?’ (Ezekiel 18:25). In the words of the Psalm we respond: ‘Lord, make me know your ways. Lord, teach me your paths. Make me walk in your truth, and teach me’ (Psalm 25:4f.). In the Gospel Jesus says to the chief priests and the elders: ‘John came to you in the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him’ (Matthew 21:32). St Paul meanwhile summons us to ‘put on the mind of Christ’ (Philippians 2:5). It is an arduous proposition, bidding us read whatever signs our times suggest in the fiery, purifying light of him who is the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End, the same today, yesterday, always.

Prerogatives

Gregory the Great, bishop of Rome 590-604, speaks directly to our times. There are good historical reasons for this — in many respects, mutatis mutandis, the circumstances of his times resemble ours. This is in itself a useful insight for us, convinced as we are of our exceptionalism in every area. In a text given us today in the office of readings, Gregory writes of Michael the Archangel: he is sent ‘so that by his action and name [meaning ‘Who is Like God?’] it may be given us to see that no one can do that which it is God’s prerogative to do’. That is precisely what we now fail to acknowledge. We are determined to be demiurges, claiming the right to create our own reality, then to demand, increasingly by means of litigation (here‘s a current example), that others affirm our self-proclaimed reality as really real, enabling the triumph of subjective perception over what is objectively given. We are increasingly up against an epistemological battle. The old prayer to Who is Like God has lost none of its pertinence: defende nos in proelio.

Good King Wenceslaus

Not to answer violence with violence; to keep our hearts open towards those in need; to pray deeply in times of persecution; to be prepared for sacrifice: we know these imperatives well. Nonetheless, to find them embodied in a specific existence, be it one that unfolded 1100 years ago, is at once unnerving and thrilling. It shows us that it is possible to follow the commandments, even in apparently impossible conditions.

The standard set by the Gospel cannot be relativised. It reveals its potential only when lived out without half measures, when, for the sake of gaining it, we lose ourselves. Thereby we see that our poor lives can, by grace, bear fruit for the kingdom. Such fruit never decays. Even after several centuries it is a source of life, joy, strength. It is radiant and unfading.

Death of Stalin

The rehabilitation of Stalin has for years been a fixture of Russian public life. I thought it time to watch at last Armando Iannucci’s The Death of Stalin from 2018. Quite how one might make of this subject a comedy had defied my imagination, but Iannucci did somehow manage. The cast is exceptional. Made up largely of theatrical actors, it confers on the film something of the dignity and intensity of a play performed on stage, which in turn justifies liberties taken with historical details and sequence. We are given to observe the dissection of a body politic reduced to a corpse. The only ligament left holding it together is fear. ‘The humor’, wrote Anthony Lane in The New Yorker, ‘is so black that it might have been pumped out of the ground. To defend the film as accurate would be fruitless. Yet the compression of time is allowable, because the panic and the fawning dread […] ring all too true. Here is a society on the verge of a nervous breakdown.’ Unsettling light is thrown on things going on right now.

Enjoyment

In Marilynne Robinson’s Jack the eponymous hero, persuaded of his dissoluteness, ever expecting the worst, is told by a preacher: ‘Mr Ames, if the Lord thinks you need punishing, you can trust Him to see to it. He knows where to find you. If He’s showing you a little grace in the meantime, He probably won’t mind if you enjoy it.’ I thought of this while watching a decent documentary about Mahalia Jackson. Thomas Dorsey said: ‘The key to Mahalia was very simple: she enjoyed her religion.’ Having grown up with Jackson’s voice (my mother had LPs), still feeling immensely comforted by it, I wonder if this is not what I’ve always sensed, somehow, without articulating it. Mahalia, a key player in the civil rights movement, had known hardship; she had few illusions about life; yet the visceral vocal power of this woman, who ‘took the beat from the nightclubs back to the church’ is charged with joyful zest. Coming to think of it, most of us could probably risk enjoying our religion a little more.

No Walk in the Woods

The Prelature of Trondheim now has an Episcopal Vicar for Synodality. What is that supposed to mean?

Our Holy Father Pope Francis likes to point out that the synodal process in which he invites us to take part seeks to learn from the Oriental Church’s experience of synodality. A qualified representative of that Church, Bishop Manel Nin, reminds us that the ‘shared journey’ at stake is not a matter merely of a crowd of believers going together for a walk in the woods, as it were, but that the Church — the ecclesia or called assembly — must walk together with Christ. The chief task of an Episcopal Vicar for Synodality is thus to help the bishop ensure that everything that happens in the Prelature, in administration and pastoral care, is focused on the Lord Jesus Christ and his Gospel, our source of new life.

From my letter to the faithful.

Art & the Weather

I smiled when, on the escalator into the Arrivals lounge at Oslo’s airport, I saw this display. It was nice to be told that a pleasant evening was waiting outside; also to see that the supposedly congenitally dour existentialism of Norwegians is able to wink at itself. Munch’s Scream is one of the world’s best-known paintings, an emblem of fright. Yet how lovely the setting is. It was the beauty of an evening rich in contrasts that pierced Munch in Nice in 1892, causing him to record the experience both with colours and with words: ‘I walked along the road with two friends, then the sky all at once turned into blood, and I sensed a great scream sounding through nature.’ There is palpable terror; perhaps also hopeful anticipation. What Munch sensed could have been birth as well as death. In any case, his record enables us, 131 years down the line, to recognise within one man’s moment of crisis the loveliness of a Mediterranean sunset. And thereby to gain a perspective on our own inward moments of extreme agitation.

Building Material

Ida Görres wrote Bread Grows in Winter in 1970. She affirmed the ‘great and promising sowing’ that had taken place at the Second Vatican Council, yet was shaken by the amount of sheer deconstruction going on in the Church. In the middle of it all, and in her own perplexity, she determinedly looked out for those trying to build on the Council’s true foundations. ‘It is for them that we, the elderly, the ones bowing out, must preserve the ground plans and seeds that now have been all but forgotten. Who knows, we might see a generation after this that will be tired of their fathers’ delight in pulling down and will look for material with which to construct time-bridges between what has gone before and what will be their own today. Development does not happen in straight lines or on a single track, the way we would like; it zigzags and spirals. At the next great turning point, the old and the true must be at hand for those who seek it. It must not have been ground to smithereens in a waste truck.’ This task, said Görres, is entrusted to two groups above all: ‘the bishops and the little ones in the people of God’.

Dennoch

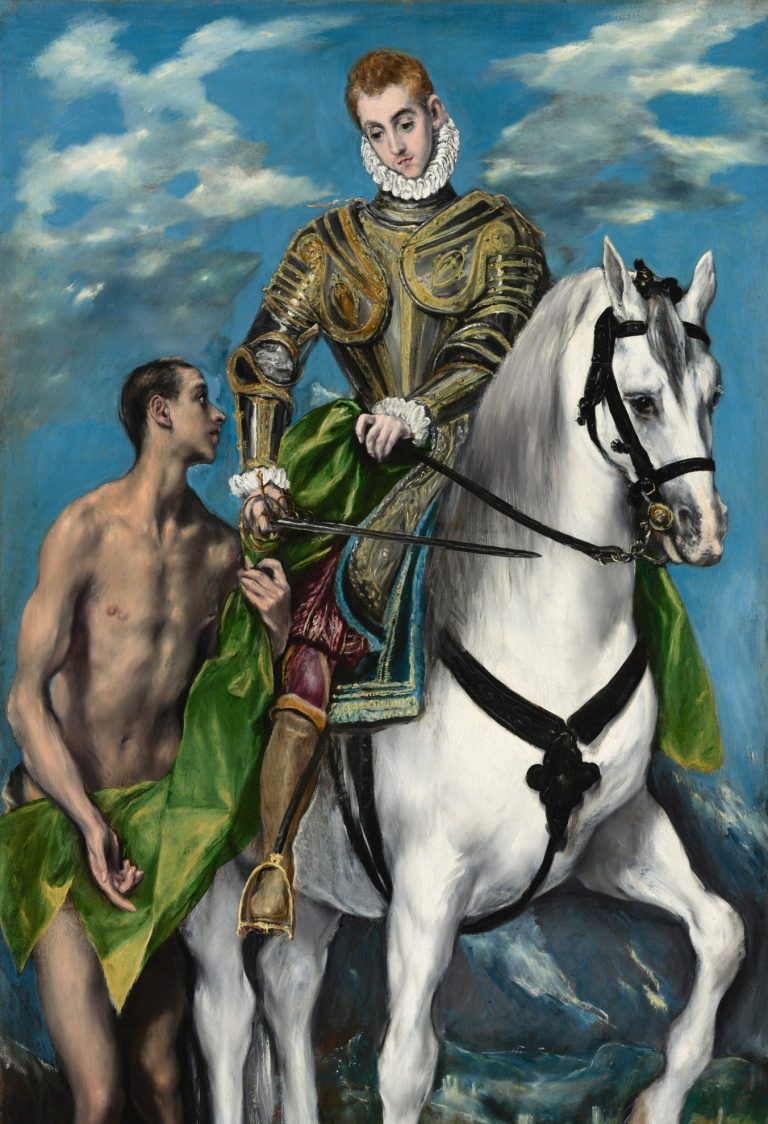

In yesterday’s keynote introduction to the Dennoch conference in Hannover – a collaborative undertaking – Dr Thomas Arnold addressed features of western modernity that pose challenges to the Church’s proclamation. Challenges are not necessarily obstacles. Though he pointed out that a rhetoric of deficit will not take us far. (I had occasion to reflect on this on my way home last night, when a man approached me on the tram and told me: ‘Religion is psychiatric illness!’) To go around proclaiming that contemporaries, for whom the question of the divine seems irrelevant, are missing out on something is unlikely to engage them. Furthermore, it plays into an attitude of condescension which the Holy Father often condemns. In Lisbon he reminded us: ‘the only valid reason I have for looking down on someone is if I am helping him or her up’. Christian evangelisation, today as in antiquity, must testify to a superabundance of life, to a plus ultra. This something is not of human making. It must stem from an encounter with God through the Church that results in a transformed life. Ultimately, the only thing that will truly impact on our self-sufficient world is the testimony of sanctity (Cf. Notebook of 11 October 2022). The illustration is El Greco’s Saint Martin and the Beggar (1597/99).

Celebrating Sorrow?

In a quirkily insightful and personal introduction to The Pillar’s weekly news summary on the Feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, Ed. Condon writes: ‘“Celebrating sorrow” is one of those quasi-oxymoronic formulations the practice of our faith can sometimes seem to throw up. But really I don’t think it’s so. Love is always, I think, bound up with a measure of sorrow […]. In many ways, at least this side of heaven, to love is to suffer, at least some of the time. But we celebrate in our sorrow, and celebrate the sorrowful love of Mary at the foot of the cross for Christ and for us, because our love is grounded in the sure hope in the resurrection.’ I agree. One of the magnificent things about Christianity is that it legitimises grief, for which secular society has no vocabulary. The only possible response to grief in a perspective void of the supernatural is outrage, easily morphed into bitterness. On 15 September each year, the Church proposes a conceptual framework for grief imbued with hope. Pergolesi set an essential text of the day’s liturgy to music. In my opinion, no interpretation of it surpasses this one.

Bronze Serpent

In one of the emblematic rebellions of Israel during the exodus from Egypt, the people were beset by serpents which bit and poisoned them. ‘And the Lord said to Moses, ‘Make a fiery serpent, and set it on a pole; and every one who is bitten, when he sees it, shall live.’ So Moses made a bronze serpent, and set it on a pole; and if a serpent bit any man, he would look at the bronze serpent and live’ (Num 21.8-9). The Church tells this story today, on the feast of the Exaltation of the Cross; for in Moses’s bronze serpents, the Fathers saw an image of Christ’s Passion. The story has an immediate, pragmatic meaning for each of us. What is wounding me, troubling me, perhaps robbing me of life? If I can name that thing and expose it to the light – set it on a pole – it will lose its power. This makes plain psychological sense. Within the mystery of faith, another dimension opens. On the cross, Christ brought light out of darkness, as at the beginning of creation; ‘and everything the light shines on becomes light’ (Eph 5.13). Even the darkness most intimate to me.

Nature

The tendency of our time is to idealize nature, with its impulses and appetites, not to transcend it. While anthropological discourse since antiquity has dwelt on what sets man apart from other species, there is a strange determination abroad, these days, to evidence that we are no more than animals. This does not mean, though, that our age is impervious to the Spirit. The claims of the soul are evident for being often expressed negatively, a function of pain. While moderns are loath to speak of God, they readily admit to feeling trapped in creaturely limitation. While giving no explicit credence to doctrines of the afterlife, they are consumed with a yearning for more. While determined to assume their incarnate humanity, they vaguely know that our body points beyond itself, since every apparent satisfaction is but achingly provisional.

From my forthcoming Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses

Letting Grief Go

Thanks to a good tip, I have discovered Rainer Kaufmann’s powerful film Running about tackling grief in terrible circumstances: an abyss of incomprehension in the wake of a suicide. Juliane has lost her partner Johann. She is caught in a web spun of different threads, some self-justifying, others self-condemning. At one level she is determined to be honest. At another, she surrenders to delusion. But when one’s world collapses, how can one know what is real? The film’s strength is its portrayal of Juliane’s gradual easing back into reality, enabled by determined friends prepared to comfort and hold, but also to speak a word of truth. At one point Juliane is told: ‘You are feeding your grief like a pet to make it stay next to you lazy and fat – for it’s the one thing still connecting you with what you have lost.’ One cannot live on loss indefinitely, even loss that seems to have taken a part of oneself away. (FAZ review here)

Baraniak

Visiting the cathedral in Poznań with the Nordic Bishops’ Conference, I paused before the tomb of Antoni Baraniak, archbishop of Poznań 1957-77. He was among the prominent Polish clerics sequestered by the Communist regime, submitted to solitary confinement, refined humiliations, and various forms of torture. The authorities’ concern was to cause a split in the Polish episcopate, mobilising Baraniak against the country’s primate, Cardinal Wyszyński. They failed. Braniak’s endurance was heroic. In the eulogy at his funeral, the cardinal spoke of the ‘remarkably strong bond’ that had formed between them, two churchmen of exceptional stature. One wonders how they would have regarded today’s ecclesiastical tussles.

You can find a Polish documentary about Baraniak here.

Weighing Up Options

The Office of Readings provides a passage (3,3) from Thomas à Kempis‘s Imitation, once upon a time a book countless Christians kept in their pocket. The challenge posed speaks powerfully right now:

‘Many listen more gladly to the world than to God; they follow more easily their physical appetite than the things that are pleasing to God. What the world offers is temporal and circumscribed, yet people serve it avidly; what I promise [says the Lord] is great and eternal, yet the hearts of mortals yield to numbness. Who serves and obeys me in all things with the sort of care that goes into service of this world and its masters?’ A little later we are told: ‘I tend to visit my elect in two ways: by temptation and by consolation.’ Is that a perspective we sufficiently consider, that our temptations might be customised, providential opportunities to grow in grace?

Irony

I’m not sufficiently a curmudgeon to miss the intended comedy of this scene from the centre of Oslo, within view of the royal palace: three public toilets painted blue, white, and red, named after the Republican virtues. At a certain level it is funny, not least because ‘Liberté’ carries a yellow notice saying ‘Not Working’.

At a deeper level, though, the scene leaves me thoughtful, sad. It seems representative of a cultural trend ever more in evidence betraying inability to relate to any exalted ideal except by means of irony. Is this because we’ve seen too much double-dealing, too little coherence in proponents of ideals? Perhaps. That’s no reason, though, to pull in the oars and let ourselves drift. No, we should take ourselves in hand, examine our lives, prepare to change them. A society – secular or sacred – without revered intelligent ideals does not just become uncreative and boring; it leaves itself open to bogusness.

The End?

Given the importance of the event we commemorate, we cannot fail to be struck by the squalor of its circumstances. We know King Herod from several passages in the Gospel, also from Josephus and other historians. We know him to be a weak ruler, conceited and unprincipled. How gladly he listened to John! How cavalierly he ignored what he heard! Over and beyond such spinelessness, today’s account presents him in a light that is positively lurid. Reclining at an executive luncheon, he is so enthralled by the suggestive charms of his stepdaughter that he promises to give her anything — well, almost anything — to show his appreciation. The gruesome request that followed shook him, yet Herod was bound by his word, his vain and presumptuous word. John was executed forthwith, with the guests still at table. A lecherous king, a jealous queen, a fickle child: should these bring the Old Testament to a close?

Pitiless Pietism

A trend much talked about in our time concerns what we might call secularist religion. People put forward very high ethical demands on the basis of a standard often recently acquired; at the same the threshold is low to thrown somebody out and say: ‘You are no longer allowed to have a voice in this assembly’. Is it a kind of pietism without grace?

Yes, and pietism shorn of grace becomes cruel.

From a conversation (in Norwegian) with the journalist Tore Hjalmar Sævik about the longing for God, human dignity, and brewing.

Ardent Shadow

I have just re-read Elisabeth de Miribel‘s life of Prince Vladimir Ghika, a remarkable man and priest, now beatified. He remained steadfast and true, ‘a teacher of hope’ as he liked to call himself, in the most diverse circumstances, from the salons of royalty to the squalid prison cell in which he died. Other, better studies have appeared since Miribel’s, yet it remains a valuable resource, not least for the extracts it contains of Ghika’s writings. This passage from one of his letters is alive within me, challenging me: ‘We suffer in proportion to our love. The capacity for suffering is within us the same as our capacity for love. It is in a way like its ardent and terrible shadow — a shadow of the same dimension, except when evening falls and shadows lengthen. A revelatory shadow that discloses us.’

Bridge-Building

‘A bishop’s ministry is ‘pontifical’. To be a pontifex is to build bridges. Given the amnesia to which the West has succumbed regarding its Christian patrimony, a chasm extends between ‘secular’ society and the Church’s sacred shore. When attempts are made to holler across, we risk misunderstanding: for even when the same words are used on either side, they have acquired different meanings. What poses as ‘dialogue’ easily ends up being a dialogue de sourds. Bridges are needed to enable encounter. Christians must present their faith integrally, without temporizing compromise; at the same time, they must express it in ways comprehensible to those ill-informed about formal dogma. They will often do this most effectively by appealing to universal experience, then trying to read such experience in the light of revelation.’

From my forthcoming book Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses

Conquered

Cinema can never have the immediacy of theatre, yet some performances are marked by such a grace of empathy that they leave the spectator with an awed sense of presence notwithstanding the screen’s mediation. To see Max von Sydow in Bille August’s Pelle the Conqueror is to see a humiliated father who has long since relinquished a sense of dignity for his own sake yet tries to maintain a semblance for the sake of his son. It makes you ache. Hal Hinson wrote: ‘This is a performance that comes from the joints and ligaments; it’s conceived in marrow. […] Von Sydow’s style has the essence of poetic compression’. Hinson is rather dismissive of the rest of the cast. I do not agree. I was stunned by this film when I first saw it 35 years ago. I find myself stunned now, having seen it again. For being an historic drama it speaks timelessly of degradation, of dreams nurtured and lost, of the complex relationship of fathers and sons, and of the startling tenderness that stirs in the human heart despite all.

Magnus

The CoramFratribus owl on a beer bottle? Indeed. The first official invitation I received qua bishop of Trondheim was to a private tour of the city’s flagship brewery, E.C. Dahl. The brewmaster had heard of my vague credentials in the world of brewing. A friendship evolved. It later extended to the brewmasters of Alstadberg and Tautra, leading to the idea of creating a new beer rooted in the rich history of our region. In the Middle Ages Trondheim (then called Nidaros) was truly a European city. The archbishopric was the centre of a vast ecclesiastical province extending to Iceland, Greenland, the Orkneys and Man. Cultural exchanges were frequent, carried by the waves of the see suggested on the beer’s label, with a red wave symbolising the legacy of the martyrs – Trondheim’s significance derived from the cult of St Olav. Inspiration, though, came also from abroad. We have named the beer after the patron of the Orkneys, a kinsman of Olav, St Magnus, who died a martyr’s death in 1117 (a story told in this hymn). It is said he visited Trondheim in 1098, the year Cîteaux was founded. The beer is to be enjoyed with moderation.