Impertinence

The memoirs of Alice Habsburg have been put into my hands. This distinguished Swede, a woman of legendary beauty, married into the epicentre of Old-World European nobility and eventually operated valiantly as a member of the Polish resistance. Her fortitude may be gauged from an account of her visit early on in WWII to Galicia, where she hoped to pick up a few things from her mansion of Busk: ‘When I reached Lvov I had someone ask the Bolshevik chief of police who resided at Busk if he would mind my coming briefly to collect some letters and other possessions I had had sent there from Zywiec. His answer was: ‘She is welcome to come, but will not return to Lvov with her head still on her shoulders.’ Having received such an impertinent reply to my courteous request, I had no choice except to travel straight to Busk.’ Alice obtained what she wanted and brought her head safely back with her, to be reunited with her husband and children. Her eldest son, the revered Dominican Fr Joachim Badeni, fought alongside Norwegian troops in the Battle of Narvik.

Aglais io

Opened

it lay before me on the path:

earth’s lightest book —

it has but two pages.

Filled with wonder I read its magic signs.

Then it ascended into the air.

No apocalypse.

Only a couple of words from summer’s

secret revelation:

Aglais io, peacock butterfly.

Christine Busta (1915–1987)

Todos, todos, todos

In Lisbon, Pope Francis insisted that the Church is ‘para todos, todos, todos’. His words are illuminated by a passage in today’s breviary from a sermon by St Augustine on the martyrdom of St Lawrence. Having celebrated Lawrence’s path to sanctity, the bishop of Hippo reminds his hearers that it is not the only path. ‘The garden of the Lord, brethren, includes – yes, it truly includes – includes not only the roses of martyrs but also the lilies of virgins, and the ivy of married people, and the violets of widows. There is absolutely no kind of human beings, my dearly beloved, who will need to despair of their vocation; Christ suffered for all. It was truly written about him that he wishes all to be saved, and to come to acknowledge the truth.’ Note the same rhetorical device: the threefold ‘includes’ which renders the threefold ‘habet’ of Augustine’s Latin. So no kind of person is excluded; but all are called to transformation in truth. The Lord’s concern is to realise our God-given potential, to make us whole and holy; not to leave us in a state of fragmentation and self-satisfied mediocrity.

Unexpected Bach

Alice Babs, born in 1924, sang in nightclubs from her teenage years. She became that most unlikely thing, a Scandinavian jazz legend. Duke Ellington said of her that her voice contained ‘all the warmth, joy of life, rhythm and tragedy that make up the inner secret of jazz’. Alice and Duke worked closely together, not least in producing their joint Serenade to Sweden.

It is surprising to find this familiar voice in a totally different register, singing an aria by Bach. Yet when you hear her perform Jesu, Jesu, Du bist mein, one of Bach’s spiritual songs, her voice seems made for it, at once limpid and intense, sincere. One genre of music can illuminate another. I dare say the same holds for much discourse.

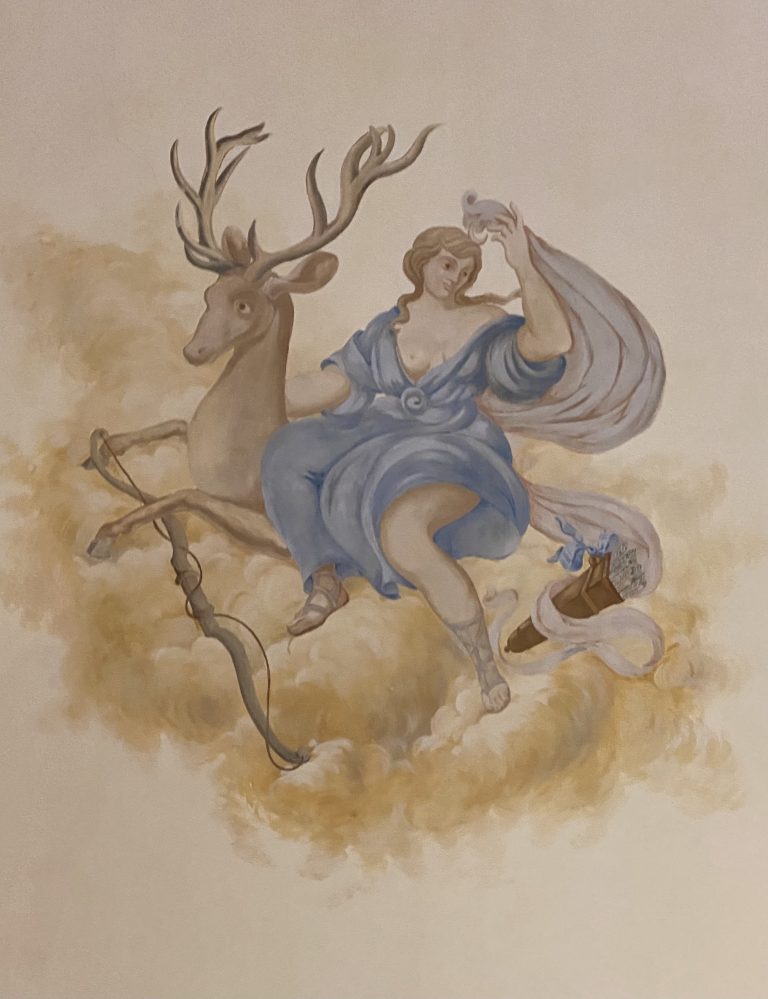

Chastity

Was it fear of nature that impelled me towards the supernatural? Such can the strength of conjecture be that it seems more real than reality. I aspired to live chastely, but regarded the endeavour as sheer mortification. It did not occur to me, I think, to see chastity as possessing an intrinsic, never mind life-giving attraction. I thought of it in negative terms, as not being, not doing what lay at the heart of the contemporary image of masculinity. Hence a further complex arose. In a culture glorifying sexual expression, was chastity not somehow unmanly?

If only I had thought of reading Cicero! He could have let me discover that, in the ancient world, the goddess of chastity, Diana, was known not only as lucifera, ‘light-bearing’, but as omnivaga, ‘roaming everywhere’, so sovereign and free.

From my forthcoming Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses

Resolution

A friend sends me this image. It sums up the experience of World Youth Day.

It needs no commentary. But a few verses from Psalm 51 come to mind:

But you delight in sincerity of heart, and in secret you teach me wisdom.

Let me hear the sound of joy and gladness, and the bones you have crushed will dance.

God, create in me a clean heart, renew within me a resolute spirit.

The message has been heard and acted upon. One can only give thanks.

Peaceful Effervescence

It is hard to describe what has been going on in Lisbon this week. I have never known anything like it. There have been people everywhere, almost all of them young, tending to gather in large clusters while waving national flags and loudly singing. Crowds have sometimes been overwhelming, filling tube trains and narrow streets. In a different setting one might have felt anxious, conscious of the risk of confrontation. Remarkable here has been the utter lack of aggressivity. Instead of closing in on themselves, groups have reached out to other groups, inviting encounter, exchanging little gifts. I had the sense that Lisbon had been turned into a sacrament of friendship, sweeping up the locals, too, in a peaceful effervescence. The experience, of course, has been brief and intense, not set to last. It does not pretend to manifest a political model of society. Yet what it confers is intensely real, authentic, leading one to ascertain that a world established on terms of fraternity is possible. To have seen this even in the twinkling of an eye is a blessing, a blessing that can alter lives. The fact that a million and a half young people choose to gather like this, for a purely idealistic purpose, without prizes to win, simply for the sake of sharing what is essential to them, is tremendous. It is news that should be on the front page of every paper.

Via Crucis

Tonight’s Stations of the Cross in the Parque Eduardo VII, led by Pope Francis, were an audacious spectacle. It is a risky business to plan liturgies audaciously. They can easily turn into mere display. That risk was averted. The ensemble was infused with creative intelligence, rooted in the mystery of Calvary and addressing the immense crowd of youth from (literally) every nation. The dancers enacted meditations on each station. They were remarkable, carried by strong choreography and beautiful music. They showed us that it is possible, without banal compromise, to represent and bear suffering with dignity, beautifully. It is a crucial lesson. For centuries Christians have communicated it through painting, sculpture, music. Many of these works are immortal. Yet it is wonderful to see the same message transmitted in a radically modern artistic idiom. Our world needs to hear it.

You can see the stations here, starting at ’45.

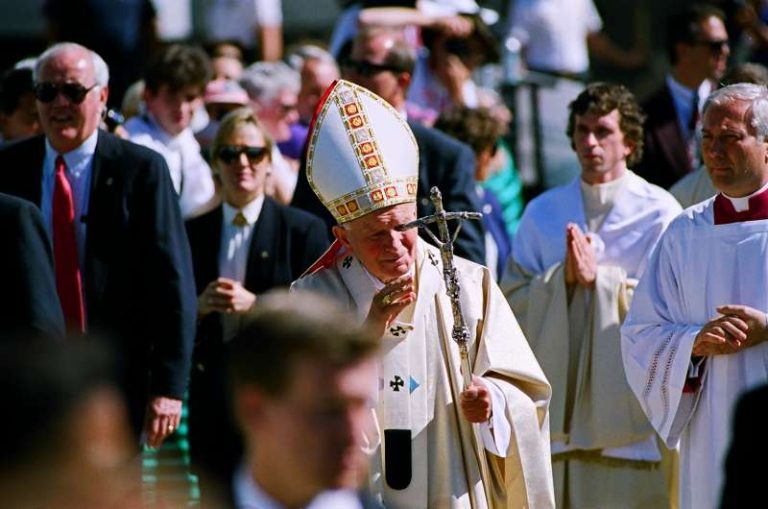

Something Great

World Youth Day, that most wonderfully improbable of gatherings, is upon us. At the Night Vigil that closed the meeting in the jubilee year 2000, Pope John Paul II, whose initiative gave birth to WYD told the world’s Catholic youth: ‘It is Jesus you seek when you dream of happiness; he is waiting for you when nothing else you find satisfies you; he is the beauty to which you are so attracted; it is he who provokes you with that thirst for fullness that will not let you settle for compromise; it is he who urges you to shed the masks of a false life; it is he who reads in your hearts your most genuine choices, the choices that others try to stifle. It is Jesus who stirs in you the desire to do something great with your lives, the will to follow an ideal, the refusal to allow yourselves to be ground down by mediocrity, the courage to commit yourselves humbly and patiently to improving yourselves and society, making the world more human and more fraternal.’

Beyond Amazon

Weltanschauung

On his 70th birthday, Romano Guardini acknowledged a debt to Max Scheler. The philosopher had once told him: ‘You must do what is intrinsic to the word Weltanschauung [consideration of the world], that is you must look at things, people, the world, but do so as a responsible Christian with a view to articulating scientifically what it is you see.’ This, said Guardini, was exactly what he had ended up spending his life doing, methodically considering ‘the encounter of faith with the world. And not just the world in a generic sense, the way theologians approach it in various modes of questioning, but the world in the particular: culture and its forms of expression, history, societal life, etc.’ After several decades of such enterprise, he poignantly concluded (in 1955, only eleven years after the end of World War II), he had come to ‘appreciate how important this work is, and what happens when it is not carried out.’ Words worth pondering.

Life in Depth

In ancient Greek a city state, the basic civilisational unit, was known as a polis. To be a ‘political being’ is to see that man, in order to thrive, must be part of a context that exceeds him. Other beings too lead an organised existence. Think of a beehive. Yet we take it for granted, not without reason, that human beings are more essentially political than bees.

I suspect that spiritual superficiality, conceptual impoverishment, and a shrinking vocabulary pose problems for public health in our time. Our lives touch great depths; we experience and feel deeply. That is simply the way we are. But ever fewer among us have words to name the depths we intuit, feel, and experience. We are vulnerable therefore to simplifying categorisations and to offers of relabelling. To live – indeed to survive – we must practise the art of living at a certain depth, there to encounter ourselves and others, to interpret the meaning of our pains and joys.

From my book Seeking Togetherness: Political Impulses launched this week.

Lasting Terror

As a story within a story dealing with modalities of artistic creation, Stefan Andres imagines the context that brought – and enabled – El Greco to paint his View of Toledo in 1599/1600. It began late one evening, writes the novelist, in which distant thunder could be heard to pass through the night ‘like a retained yawn of the night’, leaving the air heavy and thick. A new crash of thunder ‘rolled like an anchor’s chain’ out of night’s darkness. ‘[The painter] soaked the weather up like a sponge soaks up water, saturated, thoroughly shaken by bluish lights. Each rod of lightning went down his spine like a shudder of frost; the thunder resounded on his skin as much as in his ear. Then, out of his pores colours drizzled and slid onto the canvas, and there, a little later, stood Toledo on the hill in a storm, frighteningly bright in a ghostly present, leaving one to fear that the next moment would spell perpetual darkness, although only painted lightning remains, perpetuating terror.’ The account is imaginary. Yes when you look at the picture – doesn’t it ring true?

Beauty

It is good now and again to see oneself from the outside. Looking up a passage in Navid Kermani‘s fabulous Wonder Beyond Belief: On Christianity, I am struck by what he, a Shiah Muslim, says on the importance of maintaining the dimension of beauty in Christianity. He recognises that it is a battle against considerable odds: ‘I’ve only got to visit a standard Sunday Mass in Berlin to ascertain how badly today’s Christianity lacks beauty’. Much the same observation could be made throughout the world. I thought of these things recently, while visiting a fine exhibition on Urban VIII in the Palazzo Barberini. Urban was pope 1623-44, a period during which the Catholic Church, committed to the Council of Trent, saw a revolution in works for the poor, the sick, the needy. At the same time Urban VIII was a discerning patron of the arts, seeing that this dimension too is intrinsic, indeed essential, to true worship. As Kermani remarks, ‘Poverty alone makes no God great.’

Against Ease

Laure Adler is not a woman to mince words. She begins a long conversation with George Steiner: ‘There’s this thing, this arm, this deformity, this physical thing.’ Has Steiner’s withered arm made him suffer, she asks? He answers: ‘It has enabled me, I think, to understand certain conditions, certain kinds of anguish on the part of the sick that are difficult to grasp for the Apollos of this world, for those blessed to have a magnificent body and terrific health. What are the connections between physical and mental suffering and certain intellectual endeavours? That is something we still do not understand very well. Let’s never forget that Beethoven was deaf, that Nietzsche was subject to terrible migraines, that Socrates was very ugly. It is so interesting to try and see in others that which they may have had to conquer. When I meet someone I always aks myself: what has he or she lived through? What has been his or her victory — or signal failure?’

Unanswerable

The historian Zara Steiner died in 2020, ten days after her husband George, after 60 years of a marriage marked by complementarity. The two were introduced to one another by their Harvard professors who ‘bet each other that the two would get married if they ever met’. So it turned out. Zara Steiner produced massively learned work on international relations in Europe between the World Wars. Coming across The Guardian‘s obituary, I am struck by a remark regarding policies of appeasement in the 1930s: ‘Zara’s criticism of Chamberlain, Eden and Halifax, hopelessly out of their depth in the brutal world of the dictators, is unanswerable. In researching European international history between the wars, she remarked, she had encountered “few heroes, two evil Titans and an assortment of villains and knaves.”’ It is a useful point to bear in mind when reading the news now, hungry as we are for heroes and inclined ourselves to be blue-eyed about dictators. ‘In her final years’, writes David Reynolds, Zara Steiner ‘sensed that the lights were beginning to fail. Her hope was that this did not presage another triumph of the dark.’

Saving vs Serving

A young mother writes to me: ‘I have gained the trust and confidence of some priests, insight into their sufferings and dealings. In seeing their humanity, humbly, I am left with even more reverence for the priesthood, and more love, but ultimately a deeper sense of how many, even the best, have been wounded by the present climate and suffer some hopelessness where “I must save the Church” replaces “I must serve the Church”. We need shepherds and priests truly espoused to their mission, more apt to fall to their knees in hiddenness than storming through the world without a harness of humility.’

It is good to be reminded.

Tuning

I am gratefully discovering the work of Stefan Andres (1906-70), whose carefully codified fiction from the 30s and 40s evokes the experience of life under totalitarianism while carefully, but audibly, upholding an ideal of inalienable freedom. His complex novella from 1943, ‘We Are Utopia‘, recounts a scene from the Spanish Civil War. Two men from opposite sides meet during a decisive night of battle. One is a renegade priest; the other is an officer with a heavy conscience. The conversation between them is equilibrated with consummate skill, showing ability, and will, to go beyond stereotype. The ex-priest is alert to a deeper, more existential layer in the officer’s trouble. He asks: ‘Were you never happy?’ Andres describes the response: ‘”Happy?” Don Pedro spoke the word and listened to it the way a musician attends to the tone from a tuning fork.’

Many of us need to hear that tone afresh, to retune our aspirations by it.

Trauma of Loss

Fortunately, the Rabbi Sacks Foundation maintains its mailing list, enabling those of us on it to benefit still from Jonathan Sacks’ learning and insight. This week’s instalment lets an intimate experience of grief and failure shed light on a momentously mysterious passage from the Book of Numbers. Scripture lets us confront deep truths:

‘We are not always masters of our emotions. Nor does comforting others prepare you for your own experience of loss. […] We are embodied souls. We are flesh and blood. We grow old. We lose those we love. Outwardly we struggle to maintain our composure but inwardly we weep. Yet life goes on, and what we began, others will continue. Those we loved and lost live on in us, as we will live on in those we love. For love is as strong as death, and the good we do never dies.’

You can read the full text here.

Being Faced

When last week I saw this marble head, carved in the late second or early third century, the time of Caracalla, in the Archaeological Museum of Nicopolis, I was moved and puzzled. Having admired it, I walked on; but I found myself compelled to return. It was as if the lady was trying to say something to me. I could have sworn I’d seen her that same morning in downtown Preveza coming out of a hairdresser’s, her perm carefully reset. It is extraordinary how a skilled artist can convey personal presence in such a way that it arrests us still after the passage of millennia. Though to have a presence that carries, and so a gift of communion to share, I must first discover and consolidate it. Gregory the Great wrote of St Benedict that he spent a crucial time of his life ‘living alone with himself in God’s sight‘, thus preparing himself for decisive encounters. The order is taller than it may at first seem. A lot of the time, we tend rather to run away from ourselves.

Mission

When Bishop Meletios Kalamaras of blessed memory was consecrated metropolitan of Preveza on 28 March 1980, stepping into a troubled situation marked by scandals, he said: ‘The bishop, and every priest, must be a messenger of peace, a source of calm for souls which are troubled, for whatever reason. In order to be so, he must not seek honours, but must imitate Christ who, when He was reviled, did not revile in return; when He suffered, He did not threaten. And he must always be prepared to say from the depths of his heart: ‘To those who hate us and wrong us, Lord, give pardon; and grant them your bountiful mercy and your Kingdom.’ Yet for the mission of the priest, that is not enough. The chief mission of our Lord Jesus Christ was to give His soul, His whole self, to save the world. Initiating His disciples into this, the Lord taught them, saying: ‘My friends, see that no fear separates you from me. For though I suffer, yet it is for the sake of the world. If then you are my friends, imitate me.” If we truly seek remedies for clericalism, surely they are found in this mindset, this state of soul.

Orientale Lumen

St Benedict, Patron of Europe, was keenly aware of being heir to an Eastern tradition. He saw it as intrinsic to the treasure from which, in his Rule, he asked abbots to bring forth things old and new. In Orientale Lumen, Pope John Paul II submitted that ‘members of the Catholic Church of the Latin tradition must be fully acquainted with this treasure’. Drawing on the metaphor of Vyacheslav Ivanov, he insisted that the Church needs to breathe with both lungs, Eastern and Western, so to be rescued from asphyxiating provincialism and imprisonment in the immediate: ‘Today we often feel ourselves prisoners of the present. It is as though man had lost his perception of belonging to a history which precedes and follows him. This effort to situate oneself between the past and the future, with a grateful heart for the benefits received and for those expected, is offered by the Eastern Churches in particular, with a clearcut sense of continuity which takes the name of Tradition and of eschatological expectation.’ Are we now, in the Latin Church, breathing to capacity?

Summer Break

CoramFratribus will take a holiday for a couple of weeks.

I thank you for your interest in the site.

May you have a happy, restful summer – like the one sung about here.

+fr Erik Varden OCSO

Conscience

I have long valued Jennifer Bryson’s work in spreading knowledge about Ida Görres, whose insights speak clearly to the present moment. Only this week, thanks to a reference in Luke Coppen’s indispensable Starting Seven, did I learn something of Bryson’s biography and work in Guantanamo Bay. What she says about her experience there is worth reading. I was struck by her remarks on conscience. Conscience, she reminds us, is not some kind of faultless software we carry from birth; it needs formatting: ‘I didn’t know anything about conscience formation when I went to Guantanamo. And I’d been a Catholic at that point for almost 13 years. […] What I realized in Guantanamo is, first of all, that formation really needs to happen before the difficult challenges come. And because we can’t predict when those come, the time for conscience formation is right now.’ This is a theme at the heart of Görres’s work, too. ‘Understanding that there is a cosmic level of justice and that each of us, as human beings, will meet our Maker’, Bryson adds, ‘does provide a broader perspective’ on present choices.

Teleology

In an intelligent review of Matt Walsh’s What is a Woman (Notebook 3 June), Abigail Favale writes: ‘Contraception has reshaped our cultural imagination about what it means to be a man or a woman. There has been a collective forgetting about what sex is for, that it has a clear teleology around which our bodies are organized. When gender is no longer linked to generation, it becomes merely an aesthetic, a signifier without a signified. And when the signifier bears the full weight of meaning-making, the external signals of gender become intensely important—too important. We must perform and express our gender because that is all gender is now: a performative expression. These gendered signals, moreover, are increasingly shaped by the soulless forces of consumerism and pornography. We are what we watch, buy, wear, and click. Femininity and masculinity have become products, costumes, commodities.’ If one re-reads Humanae vitae in this key, one is impressed by its prescience.