Too Easy Gospel

Squalor characterises Roberto Abbado’s production of Madama Butterfly once we get into the second act – Butterfly and Suzuki go shabbily dressed and live on a building site. This jars at first. But the approach grew on me: it displays the ingloriousness of betrayal. In Act 1, the cavalier Pinkerton tells the consul in Nagasaki about his good fortune. He has acquired a lease on a house for 999 years, yet is free each month to cancel it; the bride he will put in it cost him a mere 100 yen. He sings a hymn to the man of enterprise: ‘His anchor boldly he casts at random, until a sudden squall upsets his ship, then up go sails and rigging. And life is not worth living if he can’t win the best and fairest’. The consul retorts, È un facile vangelo – ‘that gospel is too easy’. He tries to make Pinkerton see that for Butterfly the wedding is real. She gives herself to him heart and soul. Pinkerton nods pensively: he is not wicked, yet can’t conceive of anything but a provisional commitment. When he finally sees that Butterfly is a real human being, not a plaything, it is too late. The pathos of his outcry at the end is heartfelt, but shallow. The tragedy was predictable, and was his doing. Pinkerton is a type of the narcissistic lover. He comes across as startlingly contemporary. As for Butterfly, she is timeless in her patient, self-sacrificing waiting. This interpretation of the role remains unsurpassed.

Perduring Voices

It is hard to speak of the death of someone we have loved, even many years on. So it is balm to the soul to hear a voice that can – and may help us find our own voice with regard to private, hidden, perhaps still unarticulated griefs. In a recent essay Daniel Capó reflects with dignity and beauty on the anniversary of death of his younger brother: ‘When we die we begin to belong to others, to become others. Our voice perdures as a legacy in others’ souls. It is our responsibility to preserve an inheritance consigned to us from the very moment in which we knew love. Indeed, it is our duty to remain faithful to this light which we have received, to nurture it, and to protect it from the world’s miseries in order, thus, to pass it on to others. […] Our personal light presupposes the reflection of many other lights and of a love that, at times, in death can come to be terrible, yet whose mystery leaves within us a deeper, more indestructible truth.’

Mystery Undermined

A 2018 Festschrift to Fr Elmar Salmann described him as being ‘neither conservative nor liberal, but rather classical and liberating’. The source of the description is not given, but I wouldn’t be surprised if it comes from Fr Salmann himself, enunciated as an aspiration. He is a deeply aspirational man, ever in via. This comes across in a recent, readable interview with the Osservatore Romano. Among other things he says: ‘The Council led to a humanisation of the kerygma, spiritualising it in a Lucan key – we are living in the era of the third Gospel – a dramatic and extraordinary passage that has run its course in parallel to my own life. But this humanisation hasn’t made us more human. I mean, it has given no profile to the mystery. The Eucharist today is a ‘fraternal meal’, which is fair enough, but what have we done with the Mystery, the real presence, the making-present of Jesus’s passion? Tension has been pushed in the direction of making the Mystery comprehensible. As a result, we have lost it as such. Thus the humanised Christian undermines the framework of the mysteries and with them the role of the Church.’

Impact of Words

It is said of Dayan Chanoch Ehrentreu that he once prevented someone who declared disbelief in the Torah’s divine inspiration from being called upon to read the sacred text in the synagogue. In an inclusively-minded climate this might seem shocking. However, the Dayan’s reasoning was simple and sensible: had the reader ‘uttered the requisite blessing, “Our God … who gave us the Torah of truth …”, he would have committed the grave sin of giving false witness for something he did not believe. Ehrentreu always believed words had consequences.’ This belief is profoundly Biblical; indeed it encapsulates a chief dimension of Scriptural revelation. It is a perspective society urgently needs at a times when words are being devalued — and not just in secular contexts. Am I conscious of the force of the ‘Amen’ I repeatedly utter as part of liturgical prayer, of the commitment it entails?

Integrity

I have come to know and appreciate the voice of Sibylle Lewitscharoff posthumously, intrigued by obituaries published after her death on 13 May this year. A writer of virtuosity, she was also a woman of wit – and a wonderful reader. In a terrific lecture given in Vienna in 2016, she considered the lasting impact of Dante by discussing not so much the merit as the fundamental options taken by various translators, to great effect. She remarked how Dante haunts Samuel Beckett and his ‘aesthetics of negativity’, representative of much modern fiction: ‘The essence of the modern novel is brokenness. That’s what it lives on. Happiness has become a subject for kitsch.’ Dante might teach us to dare to envisage happiness, to rediscover hope. Lewitscharoff gave this aspiration voice in her writing. It also informed her life. Diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2010 she knew hardship. Not long before her death, she said with a characteristic mixture of earnestness and irony: ‘In the next world I imagine a differently constituted spiritual-embodied, simultaneously glorious beauty. I hope for a new connection with the body – I’m not so keen on the old one.’

De venerabili

Mozart’s Litanies to the Blessed Sacrament of the Altar (K 243), a youthful work, are not much performed now. They were greatly loved in their day. On 20 November 1778, having rummaged through his piles of manuscripts, Mozart wrote agitatedly to his father, ‘Now all of them, and even my Lord Prelate, have been pestering me about giving them a Litany de venerabili. I said I do not have it with me. And I was not really sure. I searched, and did not find it. I said, write to my Papa. Now they are doing whatever they want.’ Leopold found the score and sent it off, enclosing a bill. He assured his son afterwards that the work had been performed ‘when the great procession takes place, with full applause’. This music remains a catechesis in sound. Listen out for the ‘Stupendum supra omnia miraculum’. The movement ‘Viaticum’ could draw even the most hard-hearted listener to his or her knees. You can find the text of the litanies here.

Manna

The Eucharist, let’s remember, is food for pilgrims. It is not a snack for sedentary holiday makers; it is manna for those who’ve a distance to cover each day, who strain forward to be worthy, at last, to enter the Father’s house, and to feel at home there, taught by the journey through exile what homecoming means.

The Eucharist gives both a pledge and a challenge. One of today’s liturgical texts puts it thus: ‘The bread of life will incorporate us into itself if we are transformed into his likeness through a pure mind, firm faith, and perfect charity.’ That is our roadmap. In the strength of the bread from heaven, we continue on our journey of transformation with zest, great love, and gratitude.

Priesthood

Throughout the Western world there are fewer seminarians. The average age of priests is rising. Parishes close. At the same time people ask, ‘But do we need priests – aren’t they a relic of a bygone patriarchal age?’ Part of the problem is that we’ve developed a view of priesthood that is almost exclusively functional, expressed in ‘pastoral’ terms, that is, in terms of being helpful and kind to others. One does not need to be ordained to be helpful and kind. So what is the priest’s consecration for? The New Testament is radical: ‘A good shepherd lays down his life for his sheep’ (John 10.11). In this view, the pastor is called to a sacrificial existence, to be, like his Master, both shepherd and lamb, his very being caught up in a sacerdotal dynamic. I have just watched again Robert Bresson’s version of Bernanos’s Diary of a Country Priest. The film is bleaker than the novel, but reaches the same depths. I reflect: there was a time when the life of a Catholic priest was popularly perceived – the film drew great audiences – as being an oblative drama, the embodiment of radical charity grounded in, an illumined by, the mystery of the cross, a sacramental existence. This perception was true. We must acquire the words and symbols needed to express it afresh.

On Anger

We easily accuse others of disturbing our peace of mind. But can another rob me of genuine peace? Consider the scenario put before us by Dorotheus of Gaza (I am conflating a passages from Discourse 13). A monk sits quietly, minding his own business, when a brother approaches him and says something unpleasant. The monk gets angry, and justifies himself: ‘If that brother had not approached him and said those words and upset him, he never would have sinned. This kind of thinking is ridiculous and has no rational basis. For the fact that he has said anything at all in this situation breaks the cover on the passionate anger within him. A brother comes up, utters a word and immediately all the venom and mire that lie hidden within him are spewed out. He should return thanks to this brother, who has proven an occasion of profit to him.’ Unacknowledged reserves of anger, usually grounded in experiences of hurt, are major obstacles to freedom and peace in many people’s lives. We should be glad when they are revealed to us; and get on with the unpleasant but necessary work of clearing out the septic tank.

Talking Up

I’m not on the whole a great watcher of cartoons, but the Cartŵn Cymru series from 1996, Testament: The Bible in Animation, equipped with a sourcebook from the UK Bible Society, has enchanted me. The imagery is beautiful. The stories are intelligently retold. I am intrigued to find the source book suggesting taking children further into the narratives by having them listen to great music (Haydn, Britten) and read poetry. There is poetry in the films. In the one about Moses, Israel’s future liberator, seated at night in Jethro’s tent engaged in confidential exchange, says: ‘I was conceived in slavery, and born in the stink of death. Our tribes have multiplied. Rameses saw mutiny striding towards him and subtracted the space between birth and death. One swift harvest rid him of our lastborn sons and his fear. And who was I, after all this dark arithmetic, to be the remainder? A cuckoo floating into Egypt’s nest. […] I was loved, but it came a difficult way. […] I came by my life dishonestly. I am looking for another.’ What a joy to find a catechetical resource aimed at children that does not talk down to them. Moses sounds like a Welsh bard. I intend that as the highest compliment to the script writer.

Some Inkling

Jesus’ parting words to his disciples are a commission to spread the communion of divine life as widely as possible: ‘Go, make disciples of all nations; baptise them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teach them to observe all the commands I gave you.’ If we have some inkling of God’s love, we will be drawn to draw others into it. If we feel jealous of our faith; if we hoard graces received; if we want to keep others out of our private sanctuary: well, then we do not know God, Father, Son and Spirit. Then we are worshipping an idol. Our triune God shares himself infinitely while remaining undiminished. That is the mystery of the Trinity. The desire of God, Father, Son and Spirit, is to attract all mankind into their current of divine love, which is the source of all life, the foundation of all things, visible and invisible.

Womanhood

Matt Walsh’s film, What Is a Woman?, is clocking up millions of views on the internet. The question raised in it is real. It generates perplexity in our day, sometimes in unexpected fora. A year or so ago, Professor Hanna Barbara Gerl Falkowitz spoke (at 37.45) of a recent vote in the assembly of Germany’s Synodaler Weg. A call had been made for this vote to be taken by women only, something the assembly’s constitutions allowed. So far, so good. Yet when the procedure was about to begin, someone asked, ‘What, then, is a woman?’ No one could come up with an acceptable answer. A solution was found. Those members were allowed to vote who were ‘not men’. Gerl Falkowitz calls this option ‘incredibly interesting’, adding: ‘Here we are back before Simone de Beauvoir, before feminism’, with womanhood described in terms of negation, no positive definition being speakable. Intellectually, this is a deadlock. Intellectual deadlocks tend to be short-lived. Minds, men’s and women’s, do have an innate appetite for sense and an impatience with nonsense.

Polyphony

The human ear is constituted in such a way that it can hear several voices at once and perceive them as united. The history of western music is the story of development from the sublime but austere monody of Gregorian chant to ever more complex polyphony. Our minds, too, are equipped for polyphonic perception, but this faculty must be practised and refined. We seem, alas, inclined more and more to underuse it. The following remarks by Micah Mattix make me thoughtful: ‘Education, which used to be understood as an induction into the conversation that is civilization, now understands itself primarily as a problem-solving and knowledge-acquiring enterprise. It trains students in the use of a single voice. Such an education is barbaric, no matter how developed it may be. An increasingly monopolized discourse, Oakeshott writes, ‘will not only make it difficult for another voice to be heard, but it will also make it seem proper that it should not be heard.”

Entirely

A quarter of a century ago, in Paris, I went to see Corneille’s Polyeucte, the story of an early Roman martyr, performed in a small theatre. I’d read the play, but it’s a different thing to hear lines spoken aloud. I was unprepared for the force of Polyeucte’s serene confession, ‘I am a Christian, and I am one entirely’. I came out of the theatre thinking, ‘Am I?’ I thought of the experience this morning, re-reading the martyrdom of Justin and his companions. Justin was decapitated in 165, under the reign of Marcus Aurelius. Terrible things can happen in the state’s name even under an enlightened king. Asked to renege, Justin simply answered, ‘I am a Christian’. Justin was a learned man. He’d thought his way to faith and was not prepared to give up on truth: ‘No right-thinking person falls away from piety to impiety.’ Doing so would be stupid, and stupidity is unworthy of a human being. There was more to it, though. Justin could surely have made the same confession as his friend Hierax, ‘Christ is our true father, and faith in him is our mother’. Of that union I am the fruit. And would be so entirely.

Awful Grace of God

The status of Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way as a civilisation marker is well documented. In Indianapolis on 4 April 1968, facing crowds distraught and enraged at the murder of Martin Luther King, Robert F Kennedy cited from memory, ‘In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God’. This is Aeschylus in Hamilton’s version, not a very accurate one, as classicists will tell you. To read the book today is to be aware of the author’s schoolmistress-like demeanour. Yet her fundamental proposition remains fascinating: ‘Very different conditions of life confronted [the ancient Greeks] from those we face, but it is ever to be borne in mind that though the outside of human life changes much, the inside changes little, and the lesson-book we cannot graduate from is human experience.’ The Ancient Greek account of such experience remains phenomenal. Hamilton’s knowledge of that account, while imperfect, was profound, and she wrote it up beautifully.

Renew the Earth

At Pentecost we pray, ‘Come, Holy Spirit, renew the face of the earth.’ Powerful words in our present circumstances.

With so much awry in the world, we can feel powerless. It is important to resist this feeling; to realise that we can all do something to aid renewal, to prepare the ground for fraternity, friendship, justice.

This Pentecost, all principal Masses in all the Catholic churches of the Nordic countries will be offered for just peace in Ukraine. All collection will go towards the work of Caritas in Ukraine, to provide food and hygiene packages.

You can find videos presenting this initiative in English here, in Norwegian here.

Perspective

‘In a celebrated marble relief, the monumental Pazzi Madonna, the half-length Virgin and Child are set within a sharply perspectival window embrasure that both locks them in place and puts them on stage. They enact the most intense of clinches, noses and foreheads touching, eyes drilling into each other’s face. The mighty Virgin’s Roman nose overlaps her son’s in an unprecedented partial eclipse of Christ’s head; the fingers on her hands reach out to clutch him. She seems to want to shield him from the outside world – and from his preordained future.’

From James Hall’s review of the ‘largely exhilarating’ Donatello exhibition currently on at the V&A, in a basement gallery ‘as cavernous, hi-tech and high-ceilinged as a Bond villain’s lair’.

The Art of Cleaning

For most of my adult life, it has been part to my job to clean public areas, so to clean up after others. I have the highest esteem for the cleaner’s profession. So it was with interest that I recently watched Maria Hedenius’s film from 2003, The Art of Cleaning.

It is a contemplative, intelligent portrait of Mrs Wally Pettersson, for whom cleaning was no demeaning task but a way of humanising society. One senses a metaphysical dimension to her work, for Mrs Pettersson was a person alert to ultimate realities: cleaning was for her a day-to-day participation in the great task of creating kosmos out of chaos. Remarkable throughout the film is the protagonist’s matter-of-course respect for other beings, humans and animals, and her sensibility to beauty. She says, ‘I like helping others. Isn’t that the purpose of life?’

Hedenius presents before our eyes a noble life, though this is nobility of a kind we might easily overlook.

Risk of Self-Deception

A seminarian soon to be ordained a priest recently sent me Jelly Roll’s Son of a Sinner, remarking that the artist sings about ‘regret, hope, the dangers of self-deception, and the tenuousness of sobriety’. In an interview with the NYT, Roll has said he wants to perform ‘real music for real people with real problems’. He is on to something. His songs are racking up millions of views. People hear something there they don’t hear elsewhere: an engagement with life as it is. They go to Jelly Rolls for it, not necessarily to church. Yet such engagement was what people heard when they first encountered Christ’s Gospel. It was what made them see the Lord as one speaking ‘with authority’, credibly. These days, the Church is in the throes of a credibility crisis. She is perceived as eschewing accounts of things as they are, as being phoney. Such perception is sometimes biased and malicious. But not always. There are reasons for it. So preachers might take a leaf out of Jelly Roll’s book and seek to give voice to the biblical New Song (cf. Ps 96.1) as ‘real music for real people with real problems’. Deep calls out too deep (Ps 42.7).

Prospective memory

We think of the eighth century as a dark age. Out of this supposed darkness shines the Venerable Bede. Notker of St Gallen, who lived 200 years later, likened Bede to a new sun God had caused to rise, not in the East, but in the West, to illuminate the world. Bede was not an ambulant preacher with a great propaganda machinery. He was a monk who lived in peaceful stability in his Northumbrian monastery, where he was deeply content. How did he help England’s Church to find a way into the future? By engaging with the past. Bede was a careful historian, analytic in his reading of source. At the same time he read the chronicle of mankind in a supernatural, Biblical perspective. He knew that God reveals himself and acts through history; therefore history is a branch of theology. Our time is strangely historyless. What concerns us are the signs of our time. We keep assuming that some categorical rupture frees us from past experience, that the past is an encumbrance. Is that not a mark of presumption? Are not we the ones tumbling into a new Dark Age without clear points of reference? Bede offers us an alternative model of life and thought, far fresher and livelier than our weary, unanchored, hopeless postmodernism.

At One with the Task

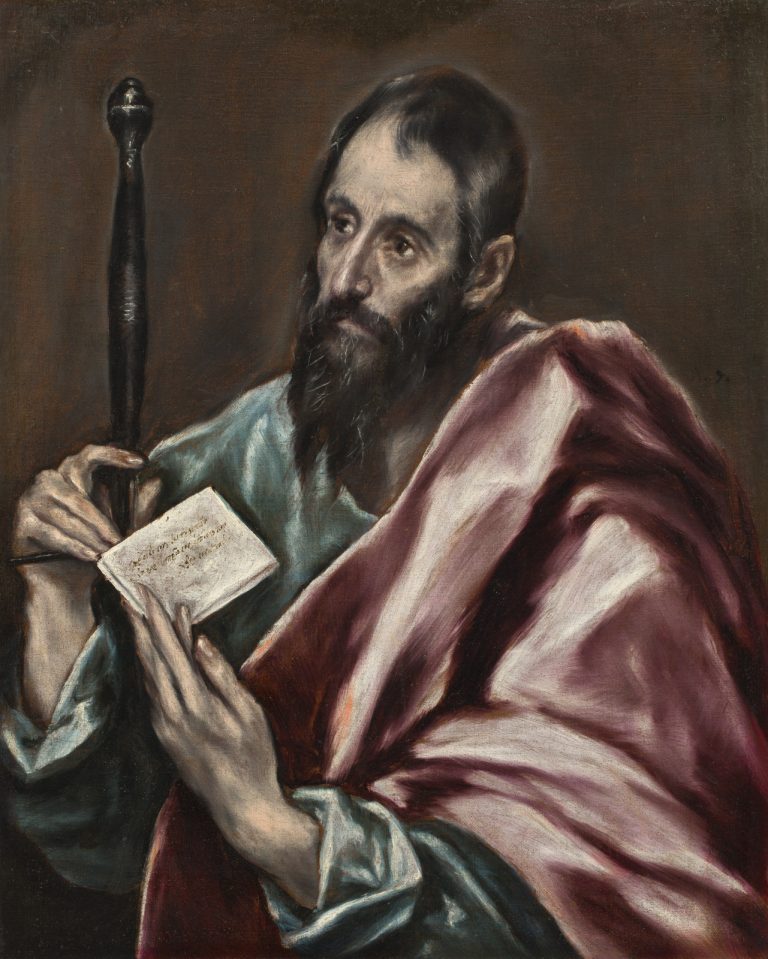

A departure gives us a chance to say things we wouldn’t otherwise say, especially when it is final. Paul’s speech in Miletus is moving. Elsewhere, too, we have heard him speak of his experiences. Think of the tirade in 2 Corinthians (‘thrice whipped, once stoned, thrice shipwrecked’); or of his correction of the Galatians (‘Let no one trouble me, I bear in my body the marks of Jesus’). At Miletus the tone is different. There is tenderness in Paul’s voice. His words testify to acceptance. He, who has preached kenosis and crucifixion to the world, shows us what the Christian condition consists in. It is as if he no longer has eyes for himself. The only thing of consequence is to complete the mission received: ‘to testify to the gospel of the grace of God’. We can sometimes perceive discipleship as a burden, not least when the world is against us. We kick against the goad, complain, and cry, ‘Usquequo? How long, O Lord?’ In the mature Paul we see a Christian fully at one with his task who finds freedom and fulfilment in it, even when he knows that ‘imprisonment and afflictions’ await him. We glimpse what it means for the glory of Jesus to be alive in a person. Then everything else recedes into the shadow, even things that normally, humanly speaking, would scare us witless.

Faith in the Real

Last week, having travelled back to Cracow from Kyiv, I saw an exhibition at the Wawel. It shows sculptures made by Johann Georg Pinsel for the church in Hodovytsya near Lviv. It was my first close encounter with Lviv Rococo. A style we normally associate with colourful excess, swooning damsels and mantelpiece ornaments is present in a quite different form: rigorous, ascetic, at once elegant and angular, as if to prove that the edges of existence can be brought into a flowing design. The theme is earnest — a Crucifixion flanked by two OT prophecies: Samson’s slaying the lion and the Sacrifice of Isaac. This may jar with us, keen as we are to stress the joy of faith. But doesn’t that mantra on its own often sound like a hollow gong? Seeing Pinsel’s work just after visiting Irpin, I thought: this is how life is. The joy of the Gospel is not infused intravenously. It is born of perseverance through perplexity and loss. In former times, Christians had courage to represent this mystery visually. They recalled that ‘The cross stands while the world revolves‘ and thus had a conceptual tool to make sense of their lives, not always bright, seeing the grandeur of suffering, which is not a question of idealising pain, but of making sense of it, building up strength to bear it. This aspect of faith needs, I think, to find new form in our time, often lost in superfluity. Cf. 1 Cor 1.17ff.

Recapitulation

Christ’s glorious Ascension restores the union of heaven and earth. But it does more, it inaugurates the recapitulation of history. Mother Elisabeth-Paule Labat has written with great perspicacity of the process in which we are caught up.

‘Growing in wisdom man will perceive the history of this world in whose battle he is still engaged as an immense symphony resolving one dissonance by another until the intonation of the perfect major chord of the final cadence at the end of time. Every being, every thing contributes to the unity of that intelligible composition, which can only be heard from within: sin, death, sorrow, repentance, innocence, prayer, the most discreet and the most exalted joys of faith, hope, and love; an infinity of themes, human and divine, meet, flee, and are intertwined before finally melting into one according to a master plan which is nothing other than the will of the Father, pursuing through all things the infallible realisation of its designs.’

Proximities

To stand under the cupola of Sancta Sophia in Kyiv is to be aligned to a chronological axis evidencing dizzying proximities. Work on this great shrine began in 1011. Olav Haraldsson, later Norway’s St Olav, buried in Trondheim, stayed in exile with Yaroslav the Wise, Great Duke of Kyiv, in 1028-29. Will he have stood within the complex of Santa Sophia? It is probable. With Yaroslav he will have discussed the significance of this church and its dedication to Christ as the Father’s incarnate Wisdom. The embodied reality of Christianity was very much part of Olav’s statesmanship and projects of legislation – a significant factor in arousing the antagonism that resulted in his death on 29 July 1030, at Stiklestad. Our modern world seems orphaned of Wisdom, often enough. Yaroslav’s Rus’ is subject to a mad attack. Olav’s Norway is susceptible to seduction by absurd irrationalities. It matters, then, to look up into the cupola and remember: the Sophia this holy place manifests is not just an optional package of life skills; it is the principle by which we, and the choices we make, will be judged.

What Endures

This icon of the Dormition was the one intact object left in a house in Lukhansk bombed to pieces by Russian occupying forces last year. It now hangs on the wall of the Greek Catholic Patriarchate in Kyiv. From the beginning of recorded time, wars have provoked existential questions: What is the point of suffering and destruction? Can there be meaning in it? It is difficult to formulate propositional answers; but one can sometimes see the contours of a response in transformed lives and gracious deeds. I am moved by the Ukrainian Catholic community’s commitment to humanitarian action. In the midst of war there is blossoming practical charity. The Gospel is enacted. Wounds are healed on the part of those who receive and on the part of those who give. Christian faith in the resurrection is personal and concrete, rooted in an historical, transformative event; but it also has symbolic, corporate power. It is not vain to speak of the resurrection of a society. One can see signs of it in Ukraine. Certain things cannot be destroyed; attempts to do so will simply manifest their indestructibility.