Beyond Mimesis

‘We should take a major step in the direction of freedom were we to free our own emotions – and also our own thoughts – from those of others: if you like me, I’ll like you; if you’re unfriendly, I’ll be unfriendly. To hear, really hear what another says is a thing of capital value. The same goes for the attempt to respond to what one has heard. But my response must be more than just a repetition of what came at me. Jesus gave us an example, responding to hate with love.’ Thus wrote Mother Christiana Reemts, abbess of Mariendonk, a few days ago; and how right she is. All too often we react instead of responding to what happens, to what gets said. Thereby we let ourselves be caught in a mimetic game of mirrors. It’s a tedious game. What we are called to in fact is freely to reveal our countenance, our true name; thereby to call forth freedom hidden in others.

To Be Loved

We are told that when St Athanasius (circa 296-373) was a child, the bishop of Alexandria one day came upon him on the beach playing church with his friends. Athanasius, playing the part of priest, was performing a baptism so exactly that the bishop affirmed it to be valid. He took the Wunderkind under his wing and raised him to become the eminent theologian we admire. The story is charming. It also has depth. It shows the astonishing linearity that can mark a life viewed in the back mirror. We may have experienced it. One day we suddenly realise: I have shaped my life freely, through uncountable unplanned vicissitudes, and yet it has somehow assumed a straight integrity, like an oak that, bursting its seed, penetrates the dark earth and stretches towards the sun. In Christian vocabulary we think of this process as a vocation story. Do we realise how extraordinary it is? I can be 100% myself, live with utter freedom, and at the same time correspond to the plan another has made for me.

In this insight we realise what it means to be loved.

The Great in the Small

When Pope John Paul II stood before the image of the Comforter of the Afflicted at Kevelaer on 2 May 1987, the first thing he said was, ‘How tiny!’ It is a paradox – this great place of pilgrimage arose around what is effectively a paper postcard. Who would have thought that such a small, humble thing could help renew a continent exhausted by hopelessness and war? We think nowadays that to enable renewal we must produce spectacular gestures. But the spectacular rarely brings comfort. There is a whiff of mendacity in the spectacular – a show is a show. Comfort, meanwhile, is true, and personal. Even with slight means we can be carriers of comfort, builders of peace. The renewal of a weary world, of a Church showing signs of weariness, begins with the renewal of particular lives. No one, nothing, not even comprehensive restructuring, can renew my life on my behalf. To kneel before Our Lady of Kevelaer is to start to see existence in a new light. Our Saviour was born in a stable. But above it angels sang.

Magnified Action

Anyone who follows human affairs with application for more than a week or two will be struck by this: how quickly we get used to war. Who now remembers there’s a war going on in Syria? Even that in Ukraine has disappeared from our headlines, once again dominated by local, pragmatic and (frankly) often pernickety concerns. Yet the wars of our time continue devastatingly; real human destinies are determined, if not destroyed, by them. After a conversation with President Zelensky last year, Timothy Snyder remarked, ‘there are moments in the world where your actions are magnified’. This is obvious for a head of state. Stefan Zweig saw such a destiny in the life of Marie Antoinette. But moments like this could come to all of us. Think of Sophie Scholl. Do we prepare ourselves – our conscience, mind, and heart – to make essential choices if called upon to do so?

If you are baffled by the background to the war in Ukraine, consider watching Snyder’s Yale lectures, The Making of Modern Ukraine.

Noctium phantasmata

Jacques Lusseyran, blind from the age of eight, reflected throughout his life on the nature of seeing and not-seeing. I am struck by this passage from his Conversation amoureuse. ‘Those with eye-sight speak so poorly about the imagination. It is as if they did not know what it is. They speak as if they were sure that it replaces everything, especially the eyes. They do not see that in fact it generates thousands of figures, combining them in different ways for days on end, leaving you in an emptiness as vast as that of migraine. I have always affirmed that there is no such thing as the night of blindness. If it does exist, it takes the form of an invasion of images. For not all are good. There are those that tell you the opposite of reality; which speak to you only of your own reality. If you have the misfortune to look too much at these, it’s the end of love.’ Such reality-subverting, self-absorbed images are like the noctium phantasmata from which we pray at compline that our eyes, inward and outward, may be freed.

Saudade

In A Poet’s Glossary, saudade is defined as a ‘Portuguese and Galician term that suggests a profoundly bittersweet nostalgia. Aubrey F. G. Bell described saudade as a “vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present, a turning towards the past or towards the future”. It is not just a nostalgia for something that was lost; it can also be a yearning for something that might have been.’

I had the privilege of discussing the sense and implications of this term, denoting a loneliness waiting to be shattered, in a recent conversation in Lisbon with António de Castro Caeiro, translator of Pindar and Aristotle. For me a privileged encounter! If you like, you can watch our exchange here, in English with simultaneous translation into Portuguese.

What’s a Good Man?

In the opening scene of Eugene Onegin, Madame Larina, Tatiana’s mother, reflects wistfully on her youth and exclaims: ‘Ah, how I loved Richardson! Ah, Grandison! Not that I ever read it.’ The fact that Tchaikovsky could expect a Petersburg audience in 1877 to pick up the reference, shows the status of Samuel Richardson’s famously long-winded novel Sir Richard Grandison, now out in a brand new 3000 pp. (!) edition. In a spirited review, Norma Clarke admits that the work is full of ‘interminable stupor-inducing exchanges’, yet insists that it has abiding worth. Jane Austen loved it and assimilated it, which is something. But what really strikes one is Clarke’s account of Richardson’s purpose in writing: ‘Was it possible to interest readers in a man who embodied Christian virtue? What would a good man be like?’ These questions are fundamental to the fiction of, say, Marilynne Robinson and Wendell Berry. One can only hope they will continue to draw forth literary creativity in an age for which the prolixity of Grandison is just too much.

Post-Secularism

In a column in this morning’s Aftenposten, the Swedish scholar Joel Halldorf asks why Swedes connect more readily than Norwegians with the spiritual dimension of contemporary literature. He writes: ‘We [Swedes] were long considered the world’s most secularised country. Over some years, however, there has been a steady movement towards faith and religiosity, especially in the world of culture. The trend has often been remarked on in the media. It indicates that we have passed from a stage of secular rupture to a post-secular stage. This doesn’t mean that all Swedes are about to return to Christianity; but materialistic atheism is not longer regarded as the obvious final stop on humanity’s religious journey. Atheism is no longer the norm; the norm is openness to a many-faceted religious search.’

This is well observed. Materialistic atheism does come across, now, as rather moth-eaten and old-fashioned. But we Norwegians tend to lag behind a little.

Wrath

Today’s gospel confronts us with God’s wrath, a theme we’d rather not think about. God is love, and if he is loving, surely he must be nice? Note, though, that the wrath in question is not the opposite of love. It does not stand for passionate anger on God’s part, but for self-enclosure on ours. Wrath as Jesus expounds it (‘he who refuses to believe in the Son will not see life; God’s wrath rests upon him’, Jn 3,36) is the opposite of life. Wrath is a state in which we confine ourselves when we refuse to receive life from a source that transcends us. To live under wrath is to feed on our own substance. Wrath finds expression in dark sadness. Life in wrath unfolds within a dank cloud of hopelessness. God’s gift to us in Christ, by the Holy Spirit, is not just survival, but life by which to flourish and bear fruit, overflowing life. Are we open to life on these terms? Or do we wrap ourselves up, be it unconsciously, in introspective, fruitless wrath?

Latin for Fun

In certain circles Latin is considered an ancient affliction like the measles, against which the wonders of progress have happily inoculated us. To be an anti-vaxxer in this regard is to set oneself up to be publicly shamed. How refreshing, then, to read a vintage essay by Joseph Epstein singing Latin’s praise. Epstein picked it up at 81, for the fun of it and because ‘I found not knowing Latin a deficiency, especially in a person of my rather extravagant intellectual and cultural pretensions’. His complex soon yielded to delight. Latin, he stresses, is a language of beauty, at once precise and subtle, gorgeously architectural. The study of Latin is a school in clear thinking, of which we’re in dire need. The Roman Catholic Church is heir to a vast intellectual and cultural heritage composed in Latin. To access it only in translation is to miss out on treasures. Who would doubt the necessity of learning German to savour and analyse Goethe? Vatican II confirmed the status of Latin as a living language. Among other things, it laid down that ‘the Latin language is to be retained by clerics in the divine office‘, for which purpose they must learn it well. Whatever happened to that conciliar counsel for renewal?

Not Numerous

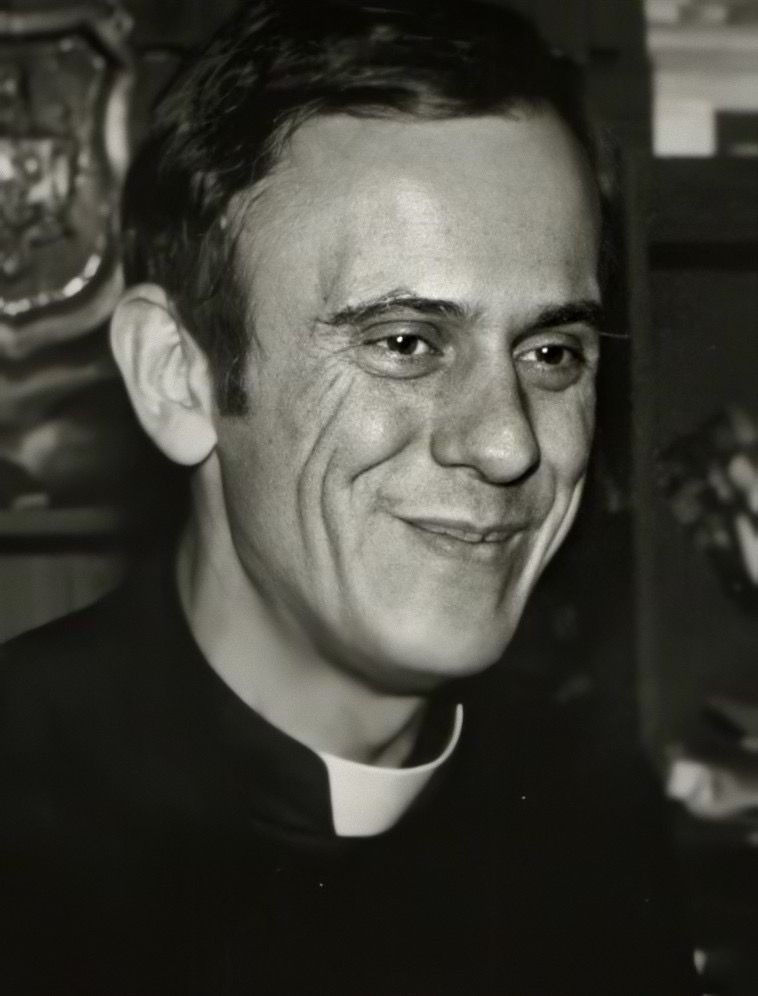

For Easter I received a letter citing something Fr Jerzy Popiełuszko once wrote. The words arose from his ministry under a totalitarian regime, but have universal relevance. ‘Truth contains within itself the ability to resist and to blossom in the light of day, even if [truth’s opponents] try very diligently and carefully to hide it. Those who proclaim the truth do not need to be numerous. Falsehood is what requires a lot of people, because it always needs to be renewed and fed. Our duty as Christians is to abide in the truth, even if it costs us dearly.’ What especially strikes me is the true observation that falsehood cannot stand on its own. It requires bands of flunkies. This gives it a ridiculous aspect it is important to remember. We mustn’t trifle with falsehood; but it is good to recognise its absurdity. What we can laugh at heartily has no power over us.

Have you seen Rafał Wieczyński’s film?

Short Pause

Gaudia Paschalia!

CoramFratribus will take a break for a few days.

I wish all readers a joyful Easter Octave.

+fr Erik Varden

Hope for the Body

The good news of the body’s significance and of the realisable, death-defying scope for human wholeness was entrusted to a ragged dozen people in a collective state of post-traumatic stress, not especially brilliant humanly speaking, but shorn by stark humiliation of presumption, so freed to proclaim a message that surpassed them. Through their unlikely mediation, this message renewed a civilisation in crepuscular decline. It revitalised the body politic. It restored hope, enabled prospect.

It might do such a thing again.

From today’s column in ABC’s La Tercera.

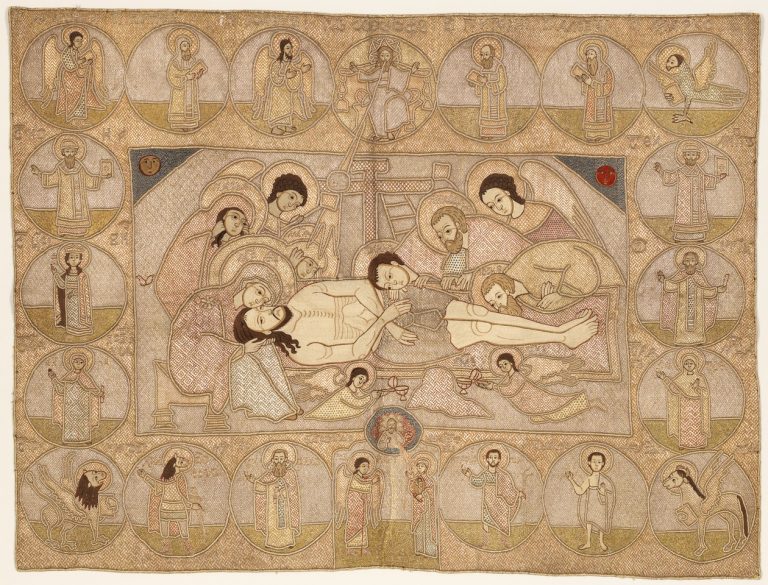

Epitaphios

In an anonymous fifteenth-century Greek poem, we find this meditation on the entombment of Christ. It speaks the ineffable.

‘The most pure Virgin saw you, Word of God, lying supine, and lamented in words befitting a Mother: ‘O my sweet springtime, my sweetest child, where has your beauty set?’ Your immaculate mother, Word of God, began a lamentation when death came over you. Women came with myrrh, my Christ, to anoint you, you, the sacred Myrrh. Death through death you destroyed, my God, with your godly power. The deceiver of men was deceived, the deceived set free from error, my God, by your wisdom.’

Philanthropy

It’s about time the Netherlands Bach Society was awarded an international prize for services rendered to mankind. What they have produced – and made available for free – these past few years is astonishing, truly an enterprise of philanthropy. I have watched and listened to Jos van Veldhoven’s production of the St John Passion with keen attention. It touches perfection, not just for its musical excellence, but for its dramatic intelligence. Raphael Höhn is a compelling evangelist. He really knows how to tell a story. And I am not sure I’ve ever heard Ach, mein Sinn, the lament following Peter’s betrayal, sung with greater intensity than that displayed here by Gwilym Bowen. By deliberate casting, almost all performers are under 35, which serves not merely to energise the performance but to make it topical. Because we’re so used, now, to thinking Christianity old and the Church tired, we risk forgetting how young most of the drama’s protagonists were. This performance has helped me to rethink many things and to experience essentials afresh.

New Reality

There’s a scene in Sigrid Undset’s conversion novel The Wild Orchid I think of often. It describes the book’s protagonist, Paul Selmer, entering St. Olav’s cathedral in Oslo very late one night, after an evening ill spent. He considers himself an agnostic but is informed about Catholic beliefs, being the lodger of a Catholic family.

Sitting alone in the dark, he sees the sanctuary light flicker in the distance. It suddenly occurs to him: if this tiny flame tells the truth, that is, if God is truly present here, then life needs to be rethought entirely; then nothing is the way he’d previously thought it might be. Easter is what enables this perception.

From a conversation with Luke Coppen for The Pillar.

A Proposal

The first half of George Weigel’s fine book about the legacy of Vatican II is in fact about the time preceding the Council. This is helpful, enabling us to understand conciliar accomplishments within an ongoing history, an oriented history of salvation. Striking is his account of the sea-change wrought by Leo XIII, symbolised somehow in the pope’s funerary monument: ‘Leo, wearing the papal tiara, stands atop the marble coffin that contains his mortal remains. His right foot is thrust forward, and his right hand is raised in a gesture of invitation, as if to say to modernity, ‘We have something to talk about. We have a proposal to make.’ With Leo XIII, a new Catholic era opened: an era in which the Church would engage modernity in an effort to convert it – and perhaps, thereby, help the modern world realise some of its aspirations to freedom, justice, solidarity, and prosperity.’

Such engagement, such help are still called for.

Beyond Purposeful

In a recent interview, Navid Kermani speaks with characteristic lucidity about the loss of gratuity. We’ve created a society in which everything is done in view of utility, profit, or gain. How to counter the trend? Listen to Schubert, and pray.

‘As human beings we are more than every before trapped in a system of purposefulness. We wake up and clean our teeth in order that our teeth be clean. Even love, even human relations are woven through with purposes, and not just of today. The truly political and anti-capitalist element of music resides in its freedom from purpose. Why do 2,000 people gather in the Philharmonie? If you’ve time, go and visit the church of Groß St. Martin here in the old town [of Cologne]. There you’ll find a monastic community, right in the middle of the city, largely unnoticed. The brethren sing and pray four or five times a day – no one knows why – but it is wonderful. […] They settle in cities, in centres, in order to pray precisely where everything round about is governed by business. They say this has intrinsic value. I, too, think that is the case. I see it makes sense politically. To break the utilitarian model, ‘We make music because …’, proposes, beyond the music itself, an alternative to the world the way it is.’ See also the Notebook entry of 30 November 2021.

What Is Man?

It seems obvious that the central challenge of Christian proclamation today is anthropological. ‘What is man?’ This question, posed in the Psalms, occupies our times intensely. Discussion is focussed on the area of sexuality, which touches the human being at its most intimate. Strong emotions arise. It is crucial to take discourse beyond emotional rhetoric. It is crucial to consider the question of human — and consequently sexual — identity in the light of God’s creative and redemptive work in Christ. From a Christian point of view, anthropology divorced from christology is bound to walk blindly in circles. Our bishops’ conference has tried to indicate the finality of existence christocentrically, hoping to enrich, perhaps even liberate, a conversation about sexuality that has gone rather stale. We do so as the Church prepares to celebrate Easter. Christ is Alpha and Omega. This is more than a formulaic truth; it is the vibrant principle by which we are called, each of us, to understand and shape our lives.

From an exchange with Madoc Cairns, in The Tablet.

Good Taste

To watch András Schiff teach is like standing next to the little child who had the courage to shout, ‘The emperor is naked!’ While remaining unfailingly courteous and kind to his pupils, he is clear in his judgements. ‘Stop the snake-charming!’ What is the difference between sentiment and sentimentality? Sentiment is emotion, part and parcel of who we are; sentimentality is ‘fake art, bad taste’. ‘What good taste is’, admits Schiff, ‘I don’t know; I just know that our world today is full of bad taste, and many people don’t know the difference.’ To discern it, education in depth is needed, and depth of global culture, but that is what, most of the time, we don’t get. ‘It’s like in medicine: if you’re an eye doctor, you don’t know where the nose is.’ The man who says these things can say them without rancour because he has acquired, by genius and patient slog, mastery of a vast repertoire. He is able to reproduce from memory subtle details from works by Bach, Scarlatti or Beethoven as if he’d just come up with them himself. Do we realise that in order to create something truly original and new, we need to have assimilated what is classical?

Annunciation

As far as we know, Isaiah’s message to Ahaz remained without effect. Ahaz despised the softly-flowing waters of Shiloh; he rejected the strategic and metaphysical resources of the City of David. Within a few years, Israel was obliterated, Judah reduced to the status of a vassal. Ahaz’s reign was regarded as a disgrace.

We find ourselves confronted with a carrying motif in Biblical revelation, that is, the lack of automatism in God’s work of salvation. The Lord’s redemptive agency manifests itself again and again as an invitation, a call awaiting an answer, showing baffling respect for our freedom to turn away in a gesture of rejection. The relationship between God and men builds on a dialectical structure, on a conversation conducted with mature deliberation. That is why the Lord’s word remains alive, able to renew our lives to this day.

From Påsketro i pesttid

Lucy

Are you familiar with the story of Lucy, a thirteen year-old from Yorkshire who just won Channel 4’s The Piano? It is always fascinating to watch super-talented young musicians, but Lucy’s case is exceptional: she is developmentally delayed, so cannot hold a conversation, and has been blind from early childhood. What is amazing is not primarily that she is blind yet plays so well. There are other blind pianists. Zhu Xiao-Mei purposely keeps her eyes shut while performing. What is amazing is that music found a way into the mind and heart of a child largely locked up in herself, and released her. It taught her stillness. It opened her to encounters. A dormant, perhaps unexpected soul-depth within her awaited the discovery of beauty. A vulnerable youngster unable to communicate verbally acquired fluency of expression through Chopin and Debussy. To hear her teacher, Daniel Bath, speak of how he went about unlocking the universe of music for her is wonderful.

Unitary Vision

At a time when many Catholic communities diminish and die, it matters to remember that others thrive and continue to transmit a living wisdom. One example is the Trappist community of Vitorchiano, wonderfully alive. Mother Cristiana Piccardo, abbess of the house 1964-88 once wrote: ‘An anguishing phenomenon [of modern society] is the intense compartmentalisation we everywhere observe. In every sphere of our lives as individuals and as societies, procedures are marked by compartmentalised specialisation. To have an illness diagnosed, we must consult a dozen different specialists; to get it cured we must move in and out of rigorously structured sectors of help and treatment in clearly differentiated units. It is not specialisation as such that is the problem, but the loss of a unitary vision of life, of man, and of the world. We may obtain specific items of information, but we have lost the ability to integrate these into a wider picture of the mystery of personhood, into the unitary complexity of man, of life.’ The monastic life well lived witnesses to this unitary vision and helps us to recover it.

Ideological Sands

Professor Cordelia Fine’s TLS review of Hannah Barnes’ Time to Think – The inside story of the collapse of the Tavistock’s Gender Service for Children is crucial reading. While taking the phenomenon of experienced gender dysphoria seriously, it shows the extent to which public discourse on this topic is determined by ideology. The result is calamitous for vulnerable youngsters whom gender ‘science’ ostensibly sets out to serve. Fine records the manipulative quashing of dissent. The scandal we associate with the Tavistock Clinic sprang from ‘the construction of institutional ignorance’. Political pressure built up over years by activist groups had created a climate that ‘made it very difficult for people to have freedom of thought’. What was effectively medical experimentation was carried out on the scantest empirical basis. Hannah Barnes’s scrupulous research, says Fine, is ‘a painful, important reminder that clinical care that promotes the wellbeing of young people experiencing gender incongruence and distress, and that protects their autonomy, cannot be built on ideological sands of ignorance, forgetting and silencing.’ Care is called for, caution, and above all wisdom, a rare bird in current debate. See also here.