Providence

Today we read in Hosea this oracle of God, ‘ I will be as the dew unto Israel: he shall grow as the lily, and cast forth his roots as Lebanon’ (14,5). The cedars of Lebanon, desired by Solomon for the building of the temple, are a symbol, in the Bible, of stability and majesty. Yet the humble lily represent a splendour Solomon in all his glory can only envy. The dew is more subtle still. Immeasurable it descends upon earth in the night, in profoundest silence, but from it springs the manna that for forty years nurtures Israel during its errancy, a tangible symbol of the mystical, super-substantial Bread. The Lord’s action cannot be limited to any particular sphere. It can be realised by any means, now spectacularly, now imperceptibly.

Let us live, then, with great attention, sharpening our sensible sight and that of our heart.

Caesar and I

It has ever been challenging for men and women of faith to position themselves within secular structures. What exactly should one, and should one not, render unto Caesar? Pinchas Goldschmidt, formerly chief rabbi of Russia, reflects on this matter in a penetrating essay written for Foreign Policy (and discussed here by Sandro Magister). He reflects on the role religion plays in Russia’s iniquitous war against Ukraine. And states with clarity how hard it is to maintain religious integrity within a totalitarian system. Some religious communities do well by the system. But what will happen if, when, the system falls? Goldschmidt makes a vital point: ‘All religious leaders should remember one fundamental principle: Their main asset is the people, not the cathedrals. And there is a heavy price to pay for a total merger with the state. Once the state and the church become one, one of them emerges as dangerously, ominously, superfluous.’ An insight worth pondering everywhere, also in the setting of an apparently liberal democracy.

Choose Light

In popular imagination, the devil’s footprint is the mark of a cloven foot. It is an appropriate image. The term ‘devil’ means ‘divider’; wherever the devil passes, it leaves division in its wake. Most of the time its action is unspectacular. Don’t think in terms of Max von Sydow’s Exorcist. Evil tends to insinuate itself. It is often sweet-talking. All the more reason, whenever we face division in ourselves or in our surroundings, to repeat our baptismal Abrenuntio, which features yearly at the Easter Vigil. It is well to affirm this profession in private peacefully but with firmness. The effort to combat evil will always be an effort in view of unity, integrity, and reconciliation in truth. The truth aspect is crucial. ‘Unite my heart to fear your name’, reads a wonderful verse in Psalm 86 (Ps 86.11 RSV). In Latin, ‘Simplex fac cor meum, ut timeat nomen tuum’. To make that prayer undistractedly is a powerful weapon against dark influence. It’s an option for the light.

Fratelli tutti

It is risky to seek a single hermeneutical key to a pontificate, which has many aspects. In Pope Francis’s case, though, there is a crucial statement in the exhortation Evangelii Gaudium published in 2013, shortly after his election. The text was a programme statement for his ministry as successor to the Apostle Peter. In his introduction he wrote: ‘The great danger in today’s world, pervaded as it is by consumerism, is the desolation and anguish born of a complacent yet covetous heart, the feverish pursuit of frivolous pleasures, and a blunted conscience [de la conciencia aislada]’ (EG, 2). The pope tirelessly calls us back to communion. He asks us to purge our faintheartedness and so to let the Spirit of Jesus transform us; to seek the nurturing joy that comes from forgetting oneself; to de-privatise our conscience in order to let be illumined by the Lord’s commandments, communicated through the Church. He stresses that fraternity is the only possible foundation for a humane society. Fraternity presupposes recognition of ourselves as children of our Father in heaven, who loves us, calls us, and renews our life. Let us, in gratitude for the Holy Father’s service these ten years, cast off self-centred desolation and learn to know the Joy of the Gospel as ours.

On Love

In Hannah Coulter, Wendell Berry lets the aged Hannah look back on the experience of losing her husband Virgil during World War II while pregnant with his child, then on her second marriage to Nathan. She is led to think deeply about the nature of love.

‘Sometimes too I could see that love is a great room with a lot of doors, where we are invited to knock and come in. Though it contains all the world, the sun, the moon, and stars, it is so small as to be also in our hearts. It is in the hearts of those who choose to come in. Some do not come in. Some may stay out forever. Some come in together and leave separately. Some come in and stay, until they die, and after. I was in it a long time with Nathan. I am still in it with him. And what about Virgil? Once, we too went in and were together in that room. And now in my tenderness of remembering it all again, I think I am still there with him too. I am there with all the others, most of them gone but some who are still there, who gave me love and called forth love from me. When I number them over, I am surprised how many there are.’

Call to Holiness

What is for you the most important aspect of the missionary dimension to which we are called?

It’s sort of fashionable these days to want to sum up the Second Vatican Council in a catchword – various attempts have been made and not all of them convince me. The question I often ask myself is this: whatever happened to the Council’s strong emphasis on the universal call to holiness? Hardly anyone talks about it. Yet we are called to be transformed in a way that corresponds to God’s original creative intention, which is a glorious intention.

From a conversation with Luca Fiore for Tracce, available here.

No Such Thing

‘There is no such thing as a casual, non-significant sexual act; everyone knows this. Contrast sex with eating – you’re strolling along a lane, you see a mushroom on a bank as you pass by, you know about mushrooms, you pick it and eat it quite casually – sex is never like that. That’s why virtue in connection with eating is basically a matter only of the pattern of one’s eating habits. But virtue in sex – chastity – is not only a matter of such a pattern, that is of its role in a pair of lives.’

Thus wrote Elizabeth Anscombe in her essay Contraception and Chastity, an immensely readable text marked by humanity, humour, and razor-sharp intelligence. To read it is to be reminded how muddled much of public discourse is on these subjects, and how we need lucidity and faith-based reason. Have a look, too, at my Notebook entry for 12 January 2023.

Humble & Strong

In these synodal times, when everyone’s voice is to be heard, we must listen not least to the voices of the saints. What have they to say to us? Cardinal Anders Arborelius asked this question last night at Vadstena, in a Mass celebrated as part of the Nordic Bishops’ Conference. Vadstena is the city of the indomitable St Birgitta. When she made instructions for the abbey church in Vadstena, a remarkable example of theological architecture, full of mystical measures, she insisted that it should be ‘humble and strong’. The Church of our time lives in a state of humiliation; this fact summons us to conversion and renewal. But what about her strength? Often she seems to be embarrassed to display it. All the more important, then, to remember that the strength in question is not hers, but the Lord’s. There is inward work, here, to be done. We shall do it on the right terms if we remember the phrase St Birgitta adopted as her motto: ‘Amor meus crucifixus est’ – ‘Mine is a crucified love’. Are we grounded in this truth?

Christian Odyssey

If you visit the abbey church of Corvey, where St Ansgar was a monk, and climb up to the ninth-century choir of the west front, you make a fascinating discovery. On the north wall is a mural painted more than 1,000 years old portraying Odysseus battling Scylla. What’s he doing there? An example of medieval syncretism? A watering-down of the Gospel in terms of classical literature? No. In the ancient Church, Odysseus was widely seen as a type not only of the Christian journey (see Notebook 5 May 2022), but of Christ. Our ancestors in the faith were convinced that Christ was the answer to the ideals and noblest dreams of all peoples and periods, the recapitulator of culture. Their conviction was well-founded. We could do with reappropriating it, should we have lost it. One of the chief Christian tasks here and now is surely to demonstrate that Christ alone corresponds to the deepest longings and best aspirations of our own age, however confusedly they may be expressed.

Of Our Word

What sets man apart from animals is not least the fact that he can talk. An animal can be faithful – any dogowner knows that – but only man can promise to be faithful. To this day, there is solemnity in the air when someone gives his or her word. Our word commits us. It also liberates us. A promise ennobles the one who pronounces it. Fidelity provides soil in which we may grow, mature, and bear fruit. When the Lord gives us his prayer – ‘Our Father, who art in heaven’ – it is not to be repeated as pious babble. The prayer provides the foundation of a binding pact. When we pray, ‘Forgive us our trespasses’, we commit ourselves to forgive. The daily bread we pray for is given us to be shared. Do we let the Lord’s name be hallowed in us? ‘My word’, says the Lord, ‘does not return to me empty’. It can, however, sink into a black hole in our consciousness and seemingly vanish. May that not happen! Let us be receptive to God’s word, then show ourselves men and women of our word.

School for Prayer

‘We do not need exhaustive experience of the human condition, or the spiritual life, to realise that we are held captive by an almost boundless world of disorder in the form of sins, affective imbalance, unhealed wounds, destructive habits, and so forth. All these things make up the impurities of our heart. We have just noted that our heart speaks through the emotions. Now, all the disorders I have listed lead to emotions in disarray. They express themselves almost without our noticing; they order us about; they tear us apart; they close us to God; and they tie us down in an automated kind of evil. All this from within our heart!’

From a letter on the prayer of the heart by the Carthusian Dom André Poisson. It is excellent Lenten reading, and you can find it right here.

Vocation

On the 365th day of Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine, Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk, chooses to speak about vocation. A significant choice on this tragic anniversary. It concerns all of us. Are we responsible stewards of God’s gift to us, resolved to carry out our task even in extremely adverse circumstances? The archbishop reminds us: ‘God calls. Man must respond. When a person responds to the call, God gives himself to that person.’ We can take God’s call for granted: ‘God never ceases to call man. If a man has already chosen his state of life by means of a definitive decision […], he must confirm that definitive decision in daily choices, daily decisions, and not change it. If that person closes in on himself and thinks of what he has received as his private property, his own treasure, he risks losing it. It sometimes happens that one who does not wish to keep listening daily to God, who calls him, can get lost and lose his direction on his journey towards daily growth. […] Then that person feels lost.’ Thus speaks one who remains steadfastly faithful, a beacon of hope for others, in the midst of war. It is only right that each of us should ask him or herself: ‘And I?’

Lenten Fast

Is there a difference between fasting and dieting?

Yes, there’s a categorical difference. Dieting has me as agent and focus, and my desire to emerge from the diet and be able to put on clothes I could put on three years ago. Fasting has its object outside myself. I deprive myself of food or some kind of enjoyment, whatever it is.

But fasting is an ecstatic practice in the strict sense of that word: it helps me to step outside myself and toward the other, and to grow in attentiveness. Dieting, I think, can sometimes be doing the opposite and make us excessively focused on ourselves.

Thin Coat

In a beautiful essay in Mentsch Magazine, Knut Ødegård writes about ‘The Playful Rolf Jacobsen‘. He speaks of Jacobsen’s enthusiasm, his onomatopoetic exuberance, his sense of the absurd; yet all this coexisted with great seriousness. Perhaps only one who takes life seriously can truly laugh (and not just snigger) at it? There was ‘something fond and vulnerable’ in Jacobsen. It found expression not least when his wife Petra died. I have rarely read a more piercing love poem than the one he wrote on that occasion. Petra’s hands had been ‘like a home’ for him, the husband and poet: ‘They said/Move in here./No rain, no frost, no fear./In that house I have lived/without rain, without frost, without fear/until time came and pulled it down./Now I am back out on the street./My coat is thin. It is about/to snow.’ Yet even in loss Jacobsen detected meaning, though he could not grasp it. ‘Indeed, he was a performer, playful — and devout.’ ‘His broad heart was home to a Chaplin-like humour, he found ‘passages everywhere and traces in people’s hearts/and paths illumined by quiet light.’

Nostalgia

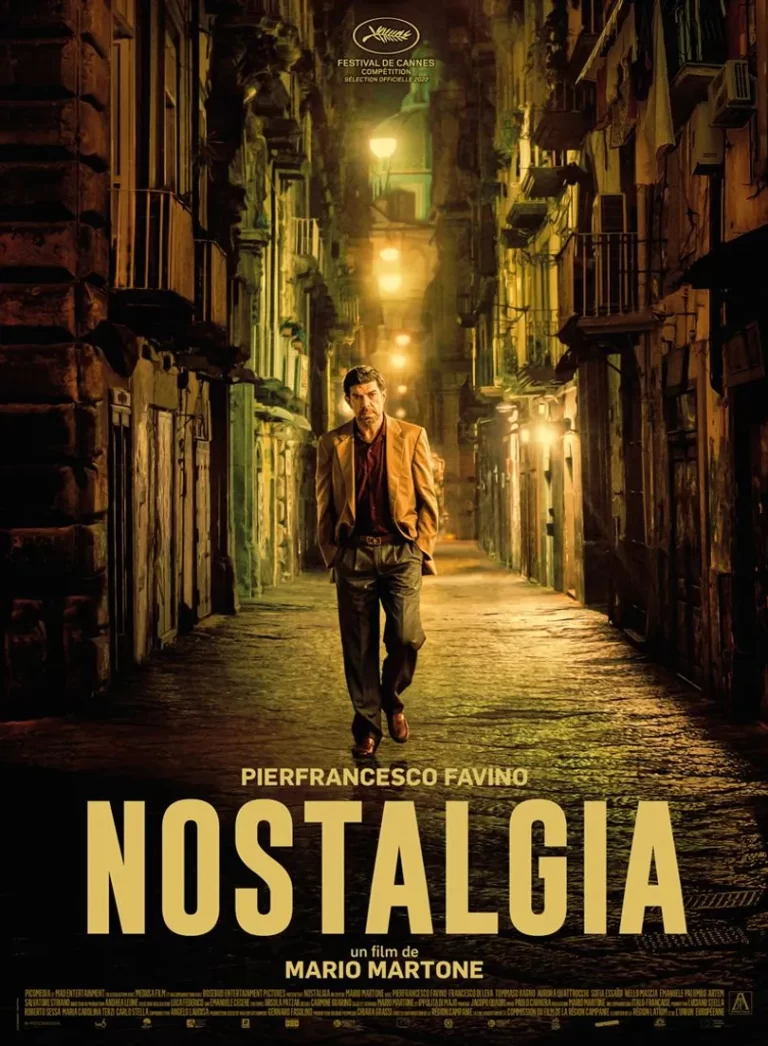

Mario Martone’s 2022 film Nostalgia is an impressive yet troubling account of a man’s resolve to come to terms with his own past. Drawn back to a place, a world, he had left hurriedly and anxiously forty years before, Felice rediscovers both its sweetness and its terror. The description of a society subdued by violence is subtle. We encounter ‘a world of danger boiled down to pregnant pauses and minute gestures’, wrote Teo Bugbee in the NYT. Yet in the midst of it, what tenderness. Felice’s reunion with his aged, frail mother is almost unbearably movingly portrayed. An idealistic young priest, a friend to the outcast, provides that rare thing: a representation in modern media of a Catholic priest who is at once credible, humane, and profoundly dedicated. As the film progresses and Felice reintegrates a part of himself he had amputated, he grows in stature and in freedom. How one would have wished such a film to end happily!

Forgiveness

Christianity preaches a high ideal of forgiveness; we are familiar with it. Yet to see it put into practice is always astonishing. At the New York Encounter, Diane Foley spoke of her experience of living through the agonising two years during which her son James, a war journalist, was held captive in Syria, and eventually murdered. She described her frustrated attempts to get the US government to intervene, or even acknowledge, her son’s abduction. At the same time she prayed. She told of how one day she knelt in church and prayed, ‘Lord, I surrender Jim to you’. Some weeks later, in the late summer 0f 2014, news of his death was certified. The Foleys’ decision then not to give into bitterness and to extend a hand of forgiveness, flabbergasted many. Mrs Foley said simply, ‘It’s what Jim would have wanted’. Speaking of her meeting with one of Jim’s captors in 2022, she told the BBC: ‘If I hate them, they have won. They will continue to hold me captive because I am not willing to be different to the way they were to my loved one. We have to pray for the courage to be the opposite.’

Patience

Scripture repeatedly presents restoration of health as recreation. In the story of Noah, the waters that, on the first day, receded from earth are drawn back over it to enable a new beginning. The image is of a world drowning (Genesis 8:6-22). Spiritual healing can pass through a stage of trauma. When an active collusion with death, addiction, or structural sin is washed away from a person’s life, he or she may feel rudderless and lost; passage into a state of grace may seem terrifying. Perseverance is required then, and solid accompaniment. The blind man in the Gospel likewise gains sight gradually. In a gesture that recalls the forming of Adam, Jesus moulds him, opening his eyes in stages until, eventually, he is able to take in reality as it is (Mark 8:22-26). To trust God is to believe that, as long as we commit ourselves into his hands, he will realise a blessed purpose even when what we presently experience is perplexity.

Absurd Ideals

Catching up with things, I have just read the obituary of a monk of Dallas, Fr Roch András Kereszty, who died on 14 December 2022. It presents the faithful, fruitful life of this learned Hungarian who settled on what he had assumed would be just ‘a vast dry prairie, the wildest and least cultured place on the continent’, and there turned into a wellspring for others. ‘His students eventually began to perceive that, behind his rough exterior – the imposing presence, the deep, loud monotone of his voice, the face that turned to a scowl whenever he tried to smile – was a man deeply in love with all that was good in those around him, and whose hopes for you always exceeded your own, which is why he could freely be so tough on you.’ He, who had practised ‘the discipline to overcome fears’ was not afraid to ‘present us with the highest, even with absurd, ideals.’

No one forgets a good teacher.

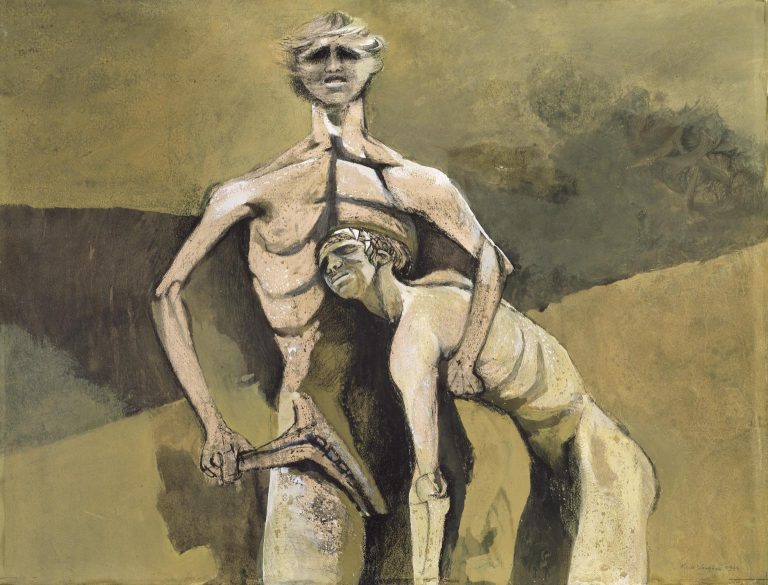

Between Brothers

‘Cain set on his brother Abel and killed him’ (Gen 4,8). The relationship between brothers — and, for that matter, between sisters — can be complicated. One is close, yet distant. It can be hard to see one another clearly. Sometimes brothers and sisters know too much about each other. A lot of prehistory feeds their relationship. Cain’s jealousy must be rooted in such prehistory. We know nothing about it, but can imagine it. He feels that Abel puts him in the shade; he can no longer look his brother in the face: ‘his eyes were downcast’. Let’s be on our guard in such instances, lest we be pulled, without noticing, into action motivated by blind anger. The question we should ask ourselves is the one God poses: ‘Why are you angry and downcast?’ Once we understand the motivation underlying a mood, we can do something about it. Something fabulous can happen. Even men’s rage, as Psalm 76 proclaims, can turn into praise, grounded in humility, marked by prayer for forgiveness, a source of new conversion.

From Aleppo

The world had largely forgotten about Syria. When we heard of the recent earthquake, eyes glazed over – we need to root such news in personal destinies. Here is a letter from an old man in Aleppo, cited on a site run by friends of my sisters in Azeir. ‘What can I say, Joseph? I’ve never seen anything like what happened, neither in war nor in other circumstances. A terrible thing! Despite all, we keep praising God. With our eyes we saw death, then again we saw life. I remained under the debris for two days, then I was saved, thanks be to God. Although my house is badly damaged, I’ve tried to make it more or less inhabitable, and I’ve once again slept at home. There are people who have slept in the streets for three days, and people who still sleep in the streets. The situation is very serious and indescribable. But let me tell you that today I am reborn to life and I thank God.’

Let us do what we can to help.

Presence

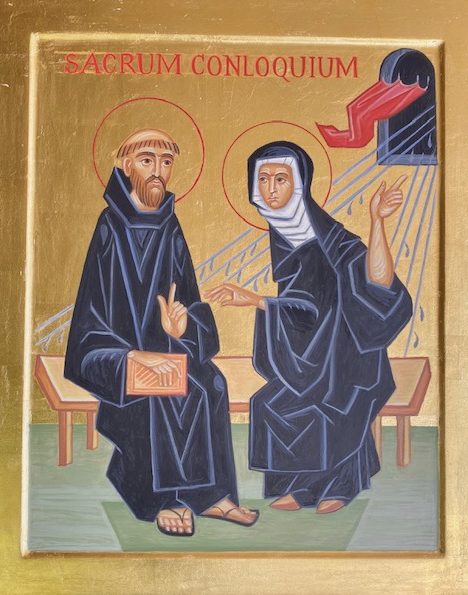

The story of Benedict’s and Scholastica’s final conversation at Monte Cassino shows that even the consummate saint may need a sister to put him in his place now and again. It also shows us the importance of meeting face to face. Scholastica took the evening bell seriously; she was a nun, after all. But she also knew that the two of them had essential things to say to each other, and that time was short. The Lord confirmed her priority by means of bad weather. So that, too, can be a sign of celestial benediction.

We whose pockets are filled with gadgets that beep, purr, flash, and stir are constantly pulled away from where we are. Scholastica reminds us of the importance of being present, of giving priority to encounters.

It was Scholastica’s ‘greater love’, we are told, that made her prayer well-pleasing. Am I someone who loves? Do I even know what love is? Or is the word to me an abstraction? These are questions we might ask ourselves today, on Scholastica’s feast day.

Someone Who Cares?

‘I yearn for someone who is not uncomfortable with my brokenness, put off by my failures, or embarrassed by my sadness. Someone who values my deeper questions, who is certain of the meaning of life and walks with me to meet it. Someone who knows me and, inexplicably, really cares for me.’

Can you recognise yourself in this statement? It resonates as the motivating intention behind a large-scale Encounter taking place over three days in New York next week. Among other things it will feature a public conversation on the theme ‘Someone with Me’, which you can follow either through the Encounter website or on www.ewtn.no.

Pope Benedict XVI insisted: ‘Each of us is willed. Each of us is loved. Each of us is necessary.’ Why do we find this so hard to believe?

Enslavement

Norway’s Bible Society has decided to use the word ‘slave’ more broadly in a translation to be published next year. The decision is pondered; indeed it has been the object of a clickable internet survey. It is fascinating that the Word of God can be interpreted, as it were, by census. But is not even the learned debate somewhat abstract? Dare we assume that our notions of slavery render the thought and practice that underlay Greek usage in the New Testament? A Norwegian thrall at the time of Olav Tryggvason is hardly comparable to a character from Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Is St Paul, who calls himself Christ’s doulos, aptly described as a ‘slave’ given the word’s contemporary resonance? Today the Catholic Church celebrates a Sudanese Saint, Josephine Bakhita, who spent twelve years as a slave. She was sold five times. She was subject to unconscionable abuse of body and soul. She was a non-human until she was declared free by a court decision in 1889. It enabled her to realise a deep desire: to be baptised and confirmed, then to join an order of sisters. In the Church she had learnt what freedom means. I wonder what Josephine had clicked, had she received an electronic questionnaire asking whether ‘enslavement’ is an adequate modern description of the Christian condition.

Becoming

The problem posed in today’s Gospel (Mark 7,1-13) is timeless. We, too, easily ‘put aside the commandments of God’, be it because we haven’t got strength to follow them, consider they’re past their sell-by date (like soured milk), or disagree with them in principle. By all means, we must use reason as we engage with divine revelation: it is a Christian imperative. But the real issue is deeper. Do I believe that God has expressed himself definitively in Christ Jesus? Do I believe that the Bible can meaningfully be called ‘Word of God’? Have I trust that God wants what is good for us, even when it is costly? We are children of an age that has made of the fitness centre an ultimate sanctuary. We energetically shape ourselves in an image that appeals to us. Have we still space, purely conceptually, for a God who may ask us to do or to become something we hadn’t thought of ourselves, who is able to realise what seems urealisable?