Pleasure

Can one live for pleasure? That is the question examined in The Triumph of Time and Disillusion by Benedetto Pamphilij, for those were the days when cardinals wrote morality plays. Handel, who met Pamphilij in Rome in 1706 set the work to music the following year. The composer was then 22 years old, the cardinal was 53. How astonished they would both have been to find their work performed in Trondheim, virtually Ultima Thule, this evening — and excellently, too. The drama, comprising four characters, is straightforward: Beauty is torn between the allurements of Pleasure and the stern admonitions of Time, helped in discernment by Disillusion, a fine contralto part. Gradually Beauty comes to see that Pleasure just isn’t a reliable long-term partner. She decides that a hierarchy of values is required to construct a life that is prospective. Increasingly she awakens to the attractiveness of truth, a category that at the outset didn’t feature in her thinking. So not a daft plot, really.

Materialist Impoverishment

In one of her inexhaustible ‘letters’, published as essays, Ida Görres insists that God is beyond any notion of gender. ‘He is One in every respect; for he is is the fullness of being. In the earthly-human realm, though, this fullness is divided into poles of generative and receiving love, of the love that protectingly and caringly maintains and the love that bears, gives birth, and nurses. God is the Father from whom all fatherhood on earth is named; and God is the maternal God ‘in whom we live and move’. Inscrutably rich and deep is the symbolism and sacred sign-value of the sexes. Devout paganism knew a lot about this (only now – at the end of modernity – have we reduced it to a matter of pure materialism). Christians ought to know more about it still. The great and venerable spiritual tradition of the Church is rich in hidden treasures, which we should once again make our own.’ This text was published in 1949, in Von Ehe und von Einsamkeit. Görres could have no idea of the urgency her call would have three-quarters of a century later. Incidentally, who reads Ida Görres nowadays? She, too, represents a treasure we should again make our own.

Faithfulness

In his eulogy at Ida Görres’s funeral, on 19 May 1971, Fr Dr Joseph Ratzinger cited a cry of pain from one of her essays. ‘What if the rebels really were to own the future? What if this process, which seems to us like destruction and betrayal, were actually God’s will and to resist it were impious and an act of petty faith? What if—an agonizing thought in the midnight hours—what if I were tied to a great but inexorably dying body, through just emotionally stirring, but ultimately subjective, unreasonable inhibitions, habits, prejudices, antiquated piety, wrongly grounded loyalty? . . . Are we living on a leaky ship sinking inch by inch, from which not only the rats but also the sensible, sober people jump off just in time?’

‘But all this questioning’, Ratzinger added, ‘is offset by a great, indestructible confidence. It is expressed in the simple yet likewise great affirmation: “I believe in God’s faithfulness”.’ Here is a perennial lesson, a source of balance and quiet joy.

Empoignement

‘I love Viktoria’, said Yehudi Menuhin about Viktoria Postnikova: ‘Such empoignement! Such power, and such wonderful commitment, strength, passion. There’s no gap between what she plays and the music. She’s off in full command.’

The remarks were made in conversation with Bruno Monsaingeon as the two listened to a recording of Bartok’s First Sonata. One can quite see what he meant here, too, where we find her playing Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto no. 1 with the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Gennady Rozhdestvensky, her husband, live at the Proms on 31 August 1979.

Though I find her musicianship even more supremely expressed in this recording, made much later in life. As an encore in Budapest she plays Schubert’s Impromptu no. 3, Opus 90 in G Flat Major. She really is one with that piano, without the slightest need to perform histrionic gestures.

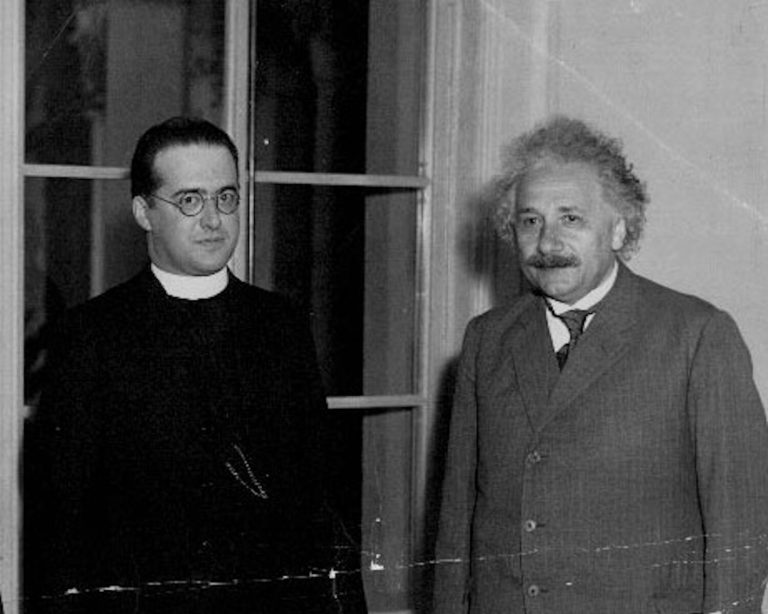

Tohu va-Vohu

‘In the beginning’, we read in Genesis 1, ‘the earth was without form and void’. What that might have been like is beyond the ken of most of us. We get tantalising impulses, however, in a recently recovered interview from 1964 with Fr Georges Lemaître. The priest-physicist, one of the first to formulate a theory of the ‘Big Bang’, insists that ‘the beginning is so unimaginable, so different from the present state of the world’ that we must first of all abstract from the image of the world as (we think) we know it: ‘there is a beginning […] in multiplicity which can be described in the form of the disintegration of all existing matter into an atom. What will be the first result of this disintegration, as far as we can follow the theory, is in fact to have a universe, an expanding space filled by a plasma, by very energetic rays going in all directions. Something which does not look at all like a homogeneous gas. Then by a process that we can vaguely imagine, unfortunately we cannot follow that in very many details, gases had to form locally; gas clouds moving with great speeds…’

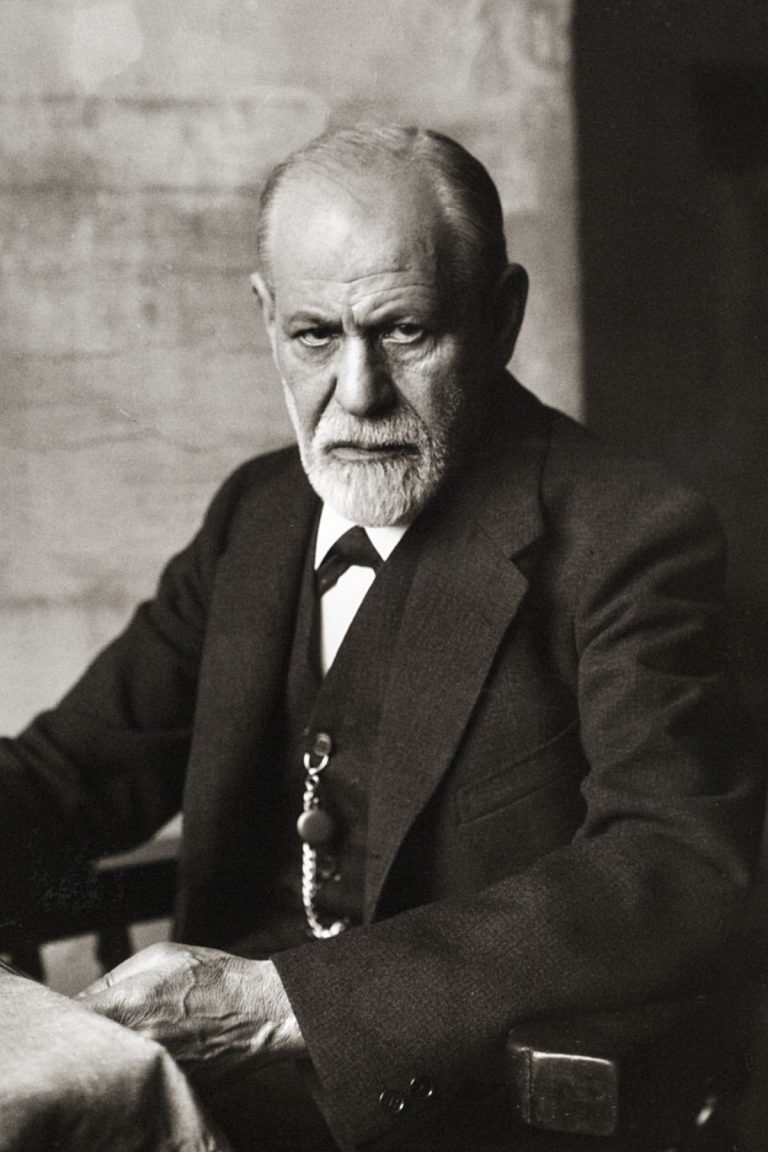

Free Before Power

A review article by Josh Cohen mentions an incident from Freud’s life that was unknown to me. It occurred when Freud, subject to keen attention from the Nazis since the Anschluss, was at last persuaded to leave Vienna on the Orient Express in June 1938.

‘Freud’s late and deeply ambivalent recruitment to the plan of escape often inspires a joint sense of frustration and respect. How, for example, could he have been so reckless as to ask the Nazi official awaiting his forced signature (on the document attesting to the “respect and consideration” shown him by the Gestapo) “whether he could add one sentence: ‘I can heartily recommend the Gestapo to anyone’”? The quip risked instant sabotage of the plan; witnesses attest to the fury on the face of the officer. Still, it is hard to hear this snatch of sharp gallows humour without feeling a wave of admiration.’

May the admiration one feels grow into fortitude.

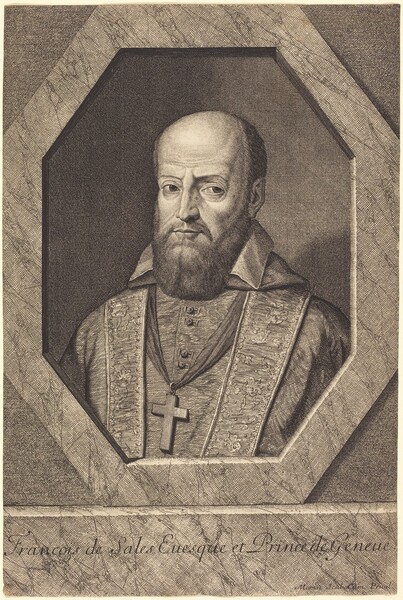

Learned Levites

I happen to own a life of St Francis de Sales published in 1928 by Eugène Julien, bishop of Arras. It carries the epigraph, ‘A mes prêtres, ce beau visage de Prêtre’, ‘To my priests I propose this beautiful type of a Priest’. How we need beautiful examples of people whose holy lives we desire to emulate! For a bishop to put forward such an example is a truly pastoral initiative. When King Henry IV offered Francis de Sales preferment that would take him from Geneva to a wealthier see, he replied: ‘Sire, I pray Your Majesty to forgive me, but I cannot accept his offer. I am a married man. I have married a poor woman, and I cannot leave her for one who is richer.’ Herein lies a whole theology of episcopal ministry. To his priests St Francis said: ‘It is not enough for clerics to strive to be holy; they must also become learned in the science of their state. In priests, ignorance is more to be feared even than sin, for by ignorance one does not merely lose oneself, one dishonours, disgraces the priesthood. […] In a priest, learning is the eighth sacrament of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. The greatest misfortunes of the Church have come when the ark of learning has been found in other hands than those of the Levites.’ Certain Levites now seem to disagree. All the more wholesome, then, is the saint’s admonition.

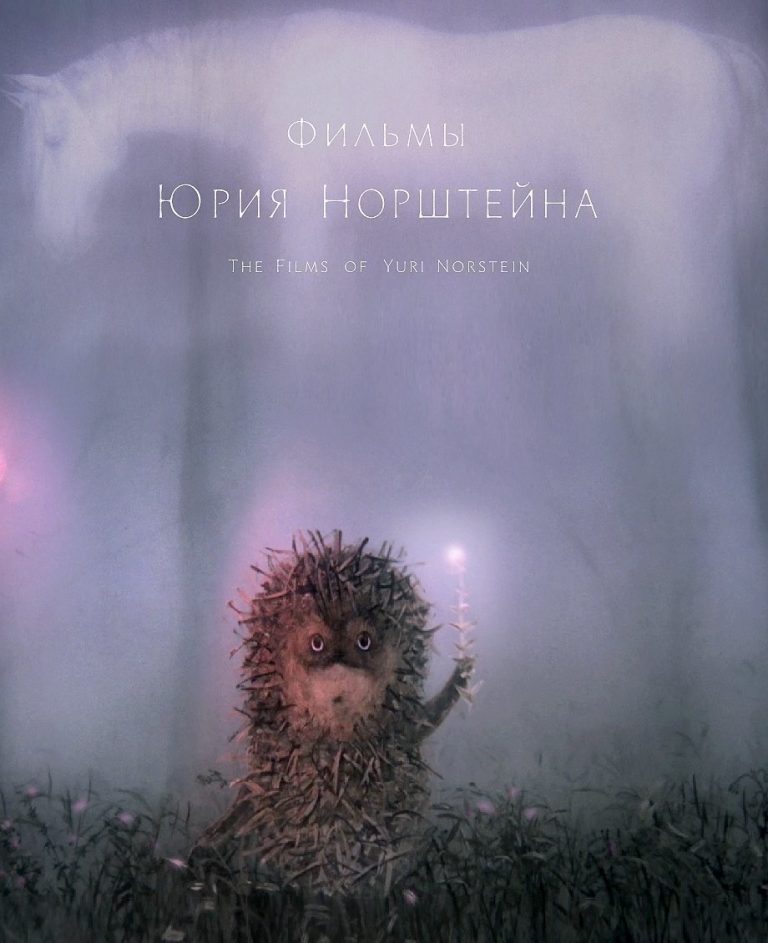

Through Fog

At a time when much about Russia inspires fear, indignation, and rage, it is important to remember that other Russia of deep humanity and openness. It does me good to revisit Yuri Norstein‘s exquisite animation Hedgehog in the Fog, a parable that does not admit straightforward interpretation. It is multi-layered and complex, yet utterly simple. It speaks to us of anxiety, of genuine peril, of unexpected allies, of the joy of reunion in friendship, and of the fidelity and affection that can be held by a jar of raspberry jam. We all go through periods when we can’t understand where we’re going; when we seemingly can’t even see our own feet on the path. Norstein said of this film: ‘Each day, Hedgehog goes to see Bear, but once he walks into the fog and comes out of it changed. This is a story about how, under the influence of circumstances beyond our conscious ken, our habitual state can suddenly turn into a catastrophe.’

Yet the catastrophe is not final. Do the stars not, at then end, shine even more brightly for what Hedgehog has been through?

The Sense of It All

Admirably, His Beatitude Sviatoslav Shevchuk continues his daily addresses to the faithful of Ukraine and to people of good will everywhere. Yesterday he uttered this cry: ‘We want to be heard in different corners of the globe, for people to hear that Ukraine is suffering, Ukraine is crying, and we are in pain.’ Yet he does not permit himself, or us, to get stuck in introspective fascination with pain. His overarching concern is to ‘discover the meaning of our Christian existence’ in the light of Christ’s mystery and on the basis of historical reality. Contemplating the sacrament of baptism, Shevchuk cites Chrysostom: ‘Let us imagine a golden cup that was damaged. No matter how it is repaired, it will always be visible that it was damaged. What must be done to remove any sign of past defects from that cup? It must be remelted, put into the fire again, remelted again, given the shape of the same cup, but it will now be new. It will have the same piece of gold, the same shape of the cup, but it will be taken out of the fire as new, it will experience a new creation and a new birth.’ To this re-making we are called. Our world needs to be made new in Christ. With the Major Archbishop we can pray: ‘Heavenly Father, grant us Christians of the third millennium to discover our deep divine sonship.’ Thus, only thus, shall we find the lasting source of justice, of peace.

Newness

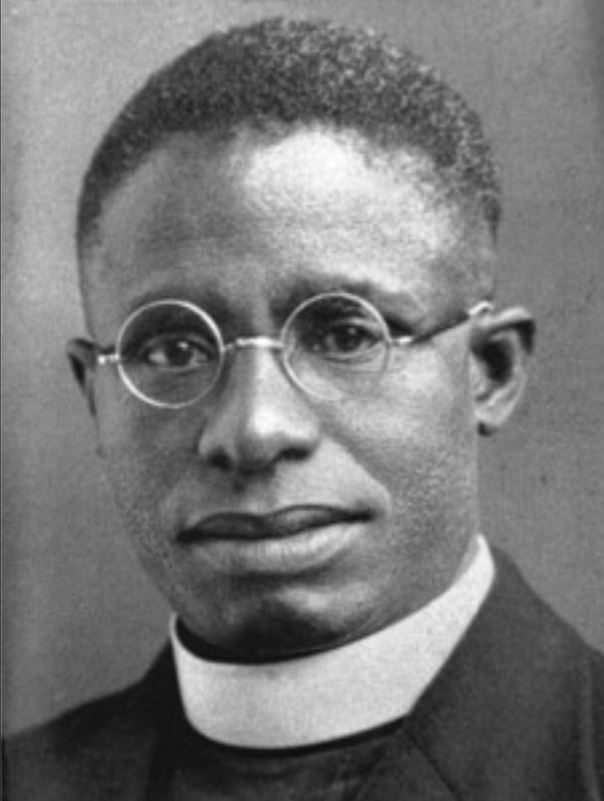

Blessed Cyprian had a keen sense of the newness of the Christian condition. It was motivated by the attraction of the Catholic faith, liturgy, and patrimony. It was also informed by awareness of what a world without Christ can look like. In 1929, when Fr Cyprian was newly ordained, working in Onitsha, a smallpox epidemic broke out in his native village. The local people attributed the spread of the disease to evil spirits. A witch hunt began. Among those singled out was Fr Cyprian’s mother Ejikwevi. She was sequestered and forced to drink poison. We can only imagine the wound left by her cruel death in the heart of her son. It is all the more striking that Fr Cyprian’s faith was marked by determined trust in providence.

Perfect Fit

People often ask: How can I pray? In a conversation with Lydia Chukovskaya on 27 September 1939 Anna Akhmatova provided an example of how not to do it. At a time of tension nationally and personally she recalled with amiable sarcasm, perhaps to distract herself, a scene from happier times: ‘Once, while waiting to try on a new dress designed by Schweitzer, the famous couturier, my cousin (who weighed more than a hundred kilos) kissed an icon of St Nicholas and said: Please, do make it fit!’

If we’re honest, don’t we often pray like that, insisting that God’s providence provide us with outfits that neither fit us nor display us to our best advantage? A prerequisite for prayer is humble, that is realistic, self-knowledge. Another is trust that God knows what is best for me, and will provide it if I am disposed to receive it. That entails willingness to let go of cherished ideas of what I want, even of what I think I really need.

Silence

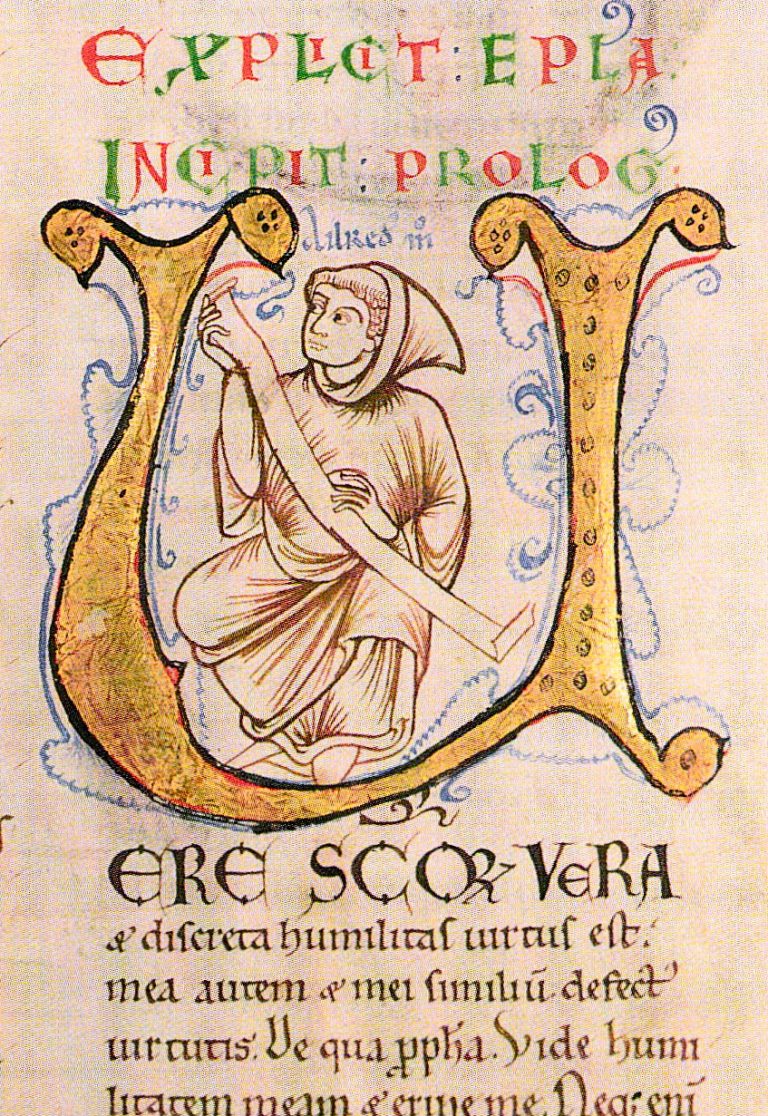

Today’s Office of Readings gives us a marvellous passage from Ignatius of Antioch’s Epistle to the Ephesians (§ 15).

‘It is better to be silent and to be real, than to talk and to be unreal. Teaching is good, if the teacher does what he says. There is then one teacher who ‘spoke and it came to pass’, and what he has done even in silence is worthy of the Father. He who has the word of Jesus for a true possession can also hear his silence, that he may be perfect, that he may act thought his speech, and understood through his silence.’

Ἄμεινόν ἐστιν σιωπᾶν καὶ εἶναι, ἢ λαλοῦντα μὴ εἶναι. Does my speech enhance being? Does it affirm reality or foster unreality?

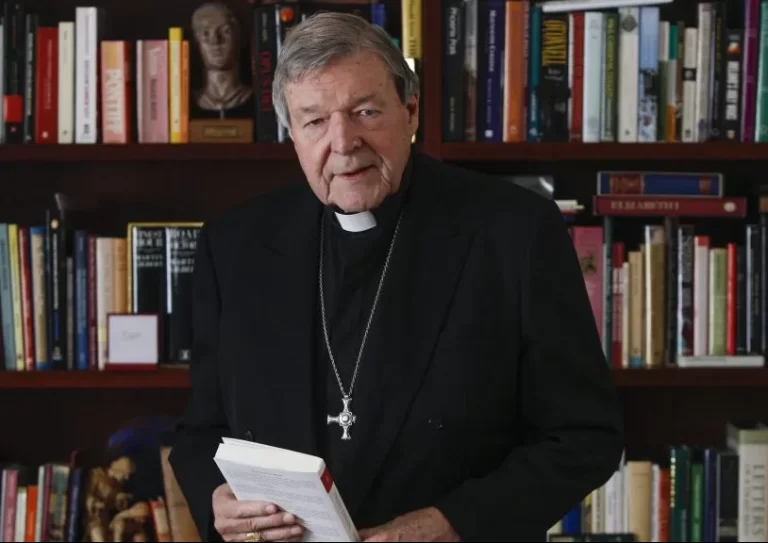

To be a Christian

Today George Cardinal Pell’s requiem is celebrated in Rome, with a final commendation given by Pope Francis. Much has been written about Pell in recent days. Matteo Mazuzzi, writing for Il Foglio, remarks that he was no natural diplomat. His outspokenness could be disconcerting – indeed disconcerts still. My remembrance of him is marked by a broadcast following his release from prison in April 2020, after months of incarceration for crimes he had not committed, after a process widely dismissed as a miscarriage of justice. What struck me was Pell’s complete lack of bitterness. With robust cheerfulness he accepted what had happened as one might accept a bad-weather day. He insisted he bore no grudge against his accusers. St Silouan used to say that heartfelt prayer for enemies is the criterion of Christian faith. In that respect Cardinal Pell has left a luminous testimony; in that light everything else he did and said must be read. In his last homily, a week ago, he urged his hearers to work for the Church’s unity, founded on charity in truth. That, too, is a lesson to remember.

Life with Reason

In a fine review article in First Things, Jennifer A Fray cites Elizabeth Anscombe‘s syllabus of errors from the mid-1980s. It is made up of ‘twenty theses, commonly held by her fellow analytic philosophers, that she deemed inimical to the Christian religion and that could, she insisted, be shown ‘false on purely philosophical grounds’.’ Nearly all these theses pit nature—conceived of as formless, and thus empty of objective meaning or purpose—against reason. I think of Chapman’s line in his Tragedy of Charles, Duke of Byron from 1608: ‘O of what contraries consists a man! Of what impossible mixtures!’ It is tragic, though (and, when you think of it, comical), that nature and reason, body and soul should be thought of in terms of contradiction. On the resolution of this quandary, the Church has crucial things to say. How we need, now, not rhetorical effusions of sentiment, but thinkers of Anscomb’s stature, integrity, and clarity apt to conduct metaphysical enquiry in the terms here outlined: ‘Metaphysics is not the project of constructing static systems of reality; rather, it is a lived praxis whose defining aim is wisdom.’

Against Inhumanity

At almost 100, Henry Kissinger remains a keen observer of world affairs. In a 2021 book he discussed the way in which the balance of power is rocked by the onset of Artificial Intelligence, which Niall Fergusson has proposed we might rename ‘Inhuman Intelligence’. Recently Kissinger applied this perspective to the war in Ukraine: ‘Auto-nomous weapons already exist, capable of defining, assessing and targeting their own perceived threats and thus in a position to start their own war. Once the line into this realm is crossed and hi-tech becomes standard weaponry – and computers become the principal executors of strategy – the world will find itself in a condition for which as yet it has no established concept. How can leaders exercise control when computers prescribe strategic instructions on a scale and in a manner that inherently limits and threatens human input? How can civilisation be preserved amid such a maelstrom of conflicting information, perceptions and destructive capabilities?’ The ascendancy of the inhuman points to the urgency of Christmas. Faith in the incarnation does not just vindicate humanity; it asserts that we depend on God to know what is, in fact, human. That assertion appears to be empirically demonstrated round about us.

Epiphany

After worshipping the Son of God, the Magi returned to their homeland ‘by another way’. Their choice was pragmatically motivated: the angel had warned them of Herod’s plots. However, there is also deep symbolic truth in their new itinerary. An encounter with Jesus is transformative. One isn’t the same afterwards; it no long seems right to keep on walking the way one walked before. We yearn for something else on which we may struggle to put our finger.

To be a Christian is to live in this state of otherness, constantly looking for the right way. The Way, of course, has a name, a face. It reveals itself to us to us on Mary’s lap and here on this altar.

Marginality

‘Ratzinger’s double name — Joseph, at birth, Benedict, as pope — refers to an unlettered saint, a poor man of God who reminds us of the Russian yurodivy, those extravagant ‘fools for Christ’ who refused to abide by the rules of the world in order to expose the sins of humanity. Joseph Ratzinger did not break any laws — he was too German for that. However, he quickly understood that in a clearly post-Christian society the light of the Church naturally orients itself — eschatologically, one might say — towards the margins. He realised that the future of the Catholic faith depends on its ability to become a counterculture formed by small creative minorities that will be a leaven of salvation. This corresponds to Biblical experience, and to Christian experience as well. We recognise here the red thread that preserved classical culture after the fall of Rome […], that saved Eastern icons from iconoclastic fury, that challenged the seemingly unstoppable power of Arianism. It was also the experience of the Jewish people through a continuous diaspora that lasted for centuries and millennia. Ratzinger saw in this a sign of God’s will.’

From a perceptive essay by Daniel Capó Laisfeldt. Spanish original here.

Benedict XVI RIP

‘In the evening of our life’, wrote St John of the Cross, ‘we shall be judged on love alone.’ It is as if we now see this faithful servant of the Lord and his Church illumined by love — he who was such a strikingly courteous man.

‘Stand firm in the faith’, Benedict XVI urges us in his spiritual testament, ‘and do not let yourselves be confounded’. What is simply transitory — polemic, sin, empty hypotheses — will pass; what is essential remains. ‘Jesus Christ is the way, the truth and the life, ‘and the Church, with all her shortcomings, is in truth his body.’ This is the confession in which the text culminates. Let us make that confession our own.

From a brief tribute to Benedict XVI

Nativitas

I wish all readers every blessing of Christmas.

Coram Fratribus will take a short break, but will be back in the early new year.

+fr Erik

Rex gentium

Today, two days before Christmas Eve, we invoke Christ as Rex gentium: ‘King of the nations and the one for whom they long.’ We may think we live in a time that has lost interest in Christian preaching. But people’s longing remains: longing for a firm foundation on which to build our lives; longing that our contradictions may be reconciled, our vital energies united. The Church confesses Christ as the corner-stone, the one who makes separate things into one. He redeems us from our presumption, from our illusion of thinking we must manage on our own, from our sin. In Mary’s Magnificat, the Mother of God proclaims: ‘He has looked upon my lowliness.’ He will look upon ours, too, if we grant him access to it. Today we might ask ourselves: What in me needs to be reconciled? Where do I need the grace of the incarnation? In order to invoke the Lord’s grace where it is really needed. And in order to pray, with expectation and trust: ‘Come, Lord Jesus, do not delay.’

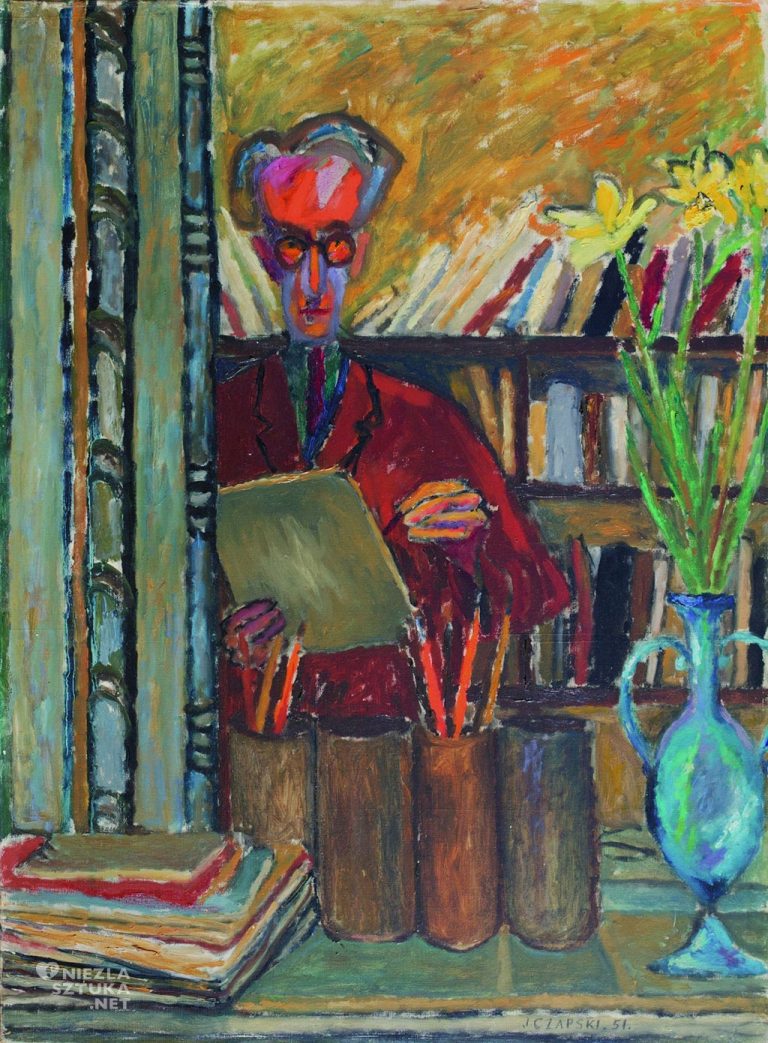

Contemporary

In an affectionate portrait of Józef Czapski, Wojciech Karpiński wrote, ‘After our first encounters, I often went back to his texts. There I recognised the sharp timbre of his voice, the way he had of emphasising certain words, printed in italics in the text, by gesture and intonation when he spoke. I recognised the same rapid and precise outlook, and the use of the present indicative to speak of Delacroix, Corot, Degas, Daniel Halévy – or of himself a few years or several decades earlier. For him, all truly important problems were contemporary.’ Czapski would equally have talked in the present tense of Aeschylus, of the Prophet Isaiah, of the birth of the Messiah in Bethlehem. How circumscribed and dull life becomes when we reduce our notion of the ‘contemporary’ to what happens to be going on just at the moment. A true perception of reality will point us towards a now that is ever-present.

Mellifluity

‘The Doctor Mellifluus‘, wrote Pius XII of St Bernard, ‘was remarkable for such qualities of nature and of mind, and so enriched by God with heavenly gifts, that in the changing and often stormy times in which he lived, he seemed to dominate by his holiness, wisdom, and most prudent counsel.’ He was also an exceptional communicator, as his epithet suggests. In a marvellous text read at Vigils today, Bernard anticipates interactive media. He has all of humanity hanging on the Blessed Virgin’s lips as she ponders her response to the Angel Gabriel’s Annunciation. ‘Answer quickly’, he urges her: ‘this is no time for virginal simplicity to forget prudence!‘ There is rhetorical delight in this passage; there is also great seriousness. Bernard reminds us that Christmas concerns each one of us. The Virgin’s ‘Yes’ is the source of our hope. We are called to make it our own.

Systemic Change

Let’s start with an easy question: What is the Incarnation?

— Well, I’m not sure it is such an easy one. First of all, it is an impossible paradox, because it is the account of the union of two incommensurate entities: the uncreated being of God and our being of dust. The great Christian wonder is before that mysterious union. […] We need to remember that in becoming flesh, the Word didn’t simply occupy one human body as a guest for 33 years. Human nature as such — that is, flesh — was invested with a potential for divinity. And so being a human being in the wake of the Incarnation isn’t the same as being a human being before the Incarnation, whether or not one believes in Christ and whether one even knows that Christ ever walked on this Earth. We like to talk about things being ‘systemic’ these days, and something systemic happened to human flesh through the Incarnation that opened it to transcendence and to eternity.

Perspective

As a young Cartusian, Dom Jean-Baptiste Porion wrote to his sister: ‘I ascertain the riches contained in a single perspective, the outline of a mountain, say, with its pine trees in the golden glory of May, in the mists of October, or whenever. We must become the mirror of this beauty and its echo. It always reveals something new, yet every time it says it all. I wonder whether travel is worth the bother.’ In a quite different cultural environment, Zhu Xiao-Mei has written of her teacher Gabriel Chodos that he taught her this: ‘In order to really learn to play the piano, to really learn music, it is as well to penetrate to the depth of a single piece as to study many different pieces. Many great researchers know this: it is by scrutinising over time a specific, circumscribed subject that one makes the most important discoveries and thereby develops a method that will allow one to work on any subject.’ How desirable to have this degree of patience, perseverance, and contemplative flair.