The Good’s Discretion

St Vincent de Paul, born in 1581, embodied the Tridentine movement. Deeply committed to the reform of the Church and clergy, he was reared on the spiritual doctrine of the Capuchin Benet Canfield, an Englishman who did much to form French Counter-Reformation spirituality. The work for the poor for which Vincent is best-known was part of an overall vision of Catholic renewal. He did not prettify corporate charity. He knew that poverty rarely ennobles people. He told a confrère: ‘The path will be long, the poor often ungrateful. The more uncouth and unjust they are, the more you must pour out your love on them. Only when they know you love them will the poor forgive you for your gifts of bread.’ This is insight born of experience, informed by a keen sense of human dignity. Many an NGO could do with taking a leaf out of Vincent’s book.

I also love this other phrase of his: ‘Noise does no good, and good makes no noise.’

Extreme Value

People sometimes speak of finding comfort in Scripture. Often enough, though, the Word of God is anything but reassuring. The beginning of the Book of Job is an example. It presents a man’s life as subject to an eternal wager, to testing that amounts to total loss. The Book of Job, let’s remember, is an extended parable, not reportage. Through exaggerated features it invites us to recognise a pattern of divine action and human response. It is not that God is cruel. He does not deal with Job the way we may, as children, have dealt with ants in an anthill, intoxicated by the disproportion between our felt omnipotence and the tiny animals’ powerlessness. The motivating factor behind the testing of Job is not sadism but the extreme value of the supernatural call addressed to man by way of an appeal to his freedom, a freedom that demands to be tested as gold is tested in the furnace.

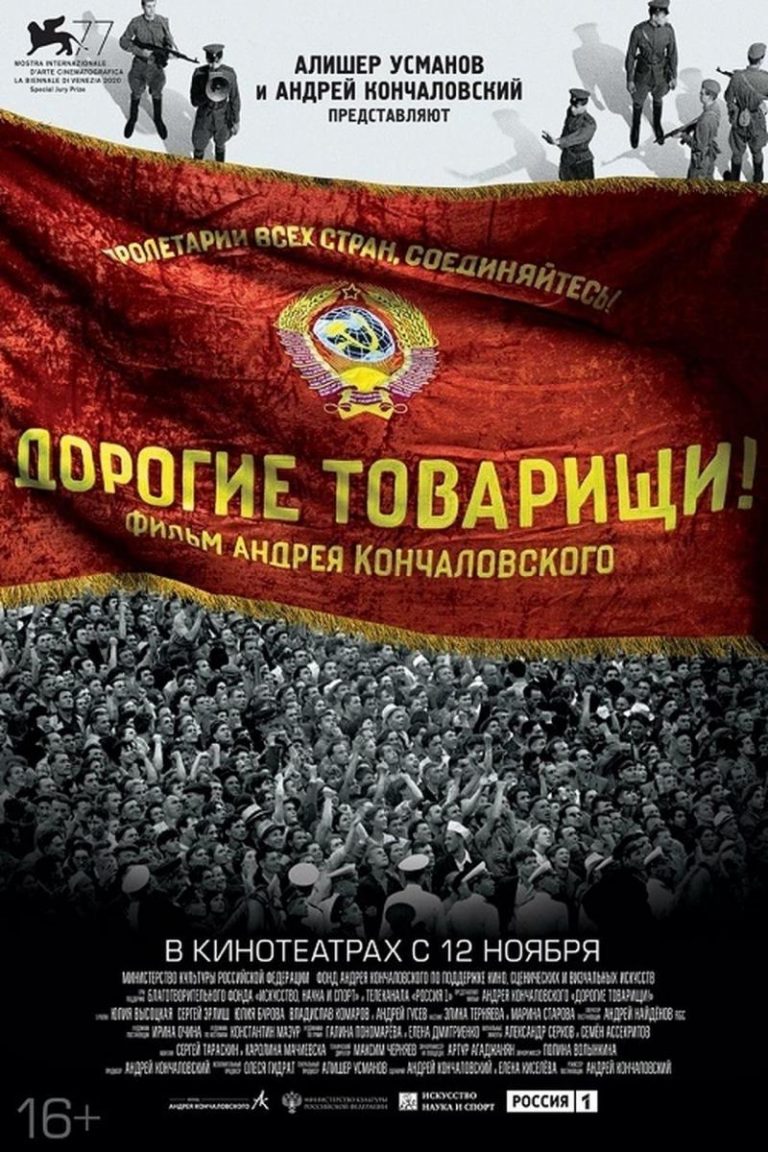

Dear Comrades

On Wednesday this week, the President of the Russian republic made a speech that began with the address, ‘Esteemed friends’, and ended with the phrase, ‘I believe in your support’. In between those statements lay a proposition of alternative reality. The stakes of absolutism, which Europeans thought was a superseded stage of societal development, are making themselves felt with force, not far away. This is a time to be mindful of where such tendencies lead. One way of doing so might be to watch Andrei Konchalovksy’s 2020 film Dear Comrades, a re-enactment of a massacre that took place in western Russia in 1962, when Red Army soldiers and KGB snipers opened fire on unarmed striking workers. As Peter Bradshaw wrote in his Guardian review last year, ‘Anger burns a hole through the screen in this stark monochrome picture’. What is our response, yours and mine, to the violent insult to righteousness being committed before our eyes?

Attention Demanded

Treasures can be found in unexpected places. One doesn’t normally look to the daily press for sapiential nourishment — but sometimes we find it there, to our delight and astonishment. An example is this essay by Katherine Rundell on John Donne (1572-1631) published in the New York Times a fortnight ago (it takes me a while to catch up). Rundell writes of Donne’s ease with extremes, of the way in which this supremely sensitive man could delight in life while looking on death fearlessly. From his practised capacity for tension sprang curiosity, sympathy, compassion, above all determined attention:

‘Wake, his writing tells us, over and over. Weep for this world and gasp for it. Wake, and pay attention to our mortality, to the precise ways in which beauty cuts through us. Pay attention to the softness of skin and the majesty of hands and feet. Attention — real, sustained, unflinching attention — is what this life, with its disasters and delights, demands of you.’

Rest

The notion of rest is important in ascetic vocabulary. The Greek Fathers designated it as hēsychia, a term rendered in Latin as pax. What the Fathers had in mind was not relaxation, but a state of inward balance in which the composite elements that make up human existence are gradually harmonised, attuned to the Logos, much as the members of an orchestra, before a performance, tune their instruments to the A intoned by the First Violin.

Often enough, we are conscious that this harmony and the beneficent balance it induces are absent from our lives. What to do then? An avenue is indicated by the poet Reiner Kunze, who once wrote that a poem is unrest come to rest: ‘Das gedicht ist zur ruhe gekommene unruhe‘. What if the fundamental human task were poetic, if the chief challenge before us were to make of our lives such a poem?

Who We Are

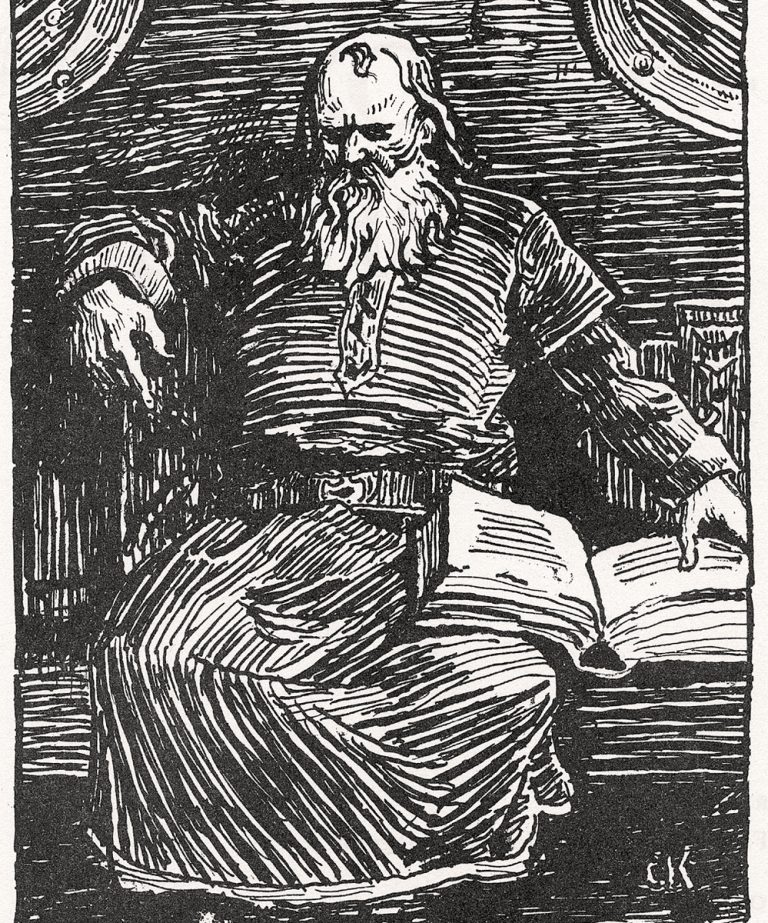

An artefact on display in a fine exhibition in Hildesheim’s Dommuseum is a candlestick made in the Meuse Delta around 1180. It represents the three continents known at that time – Europe, Africa, and Asia – as female figures. How interesting to note the attributes ascribed to them.

Asia holds a filled vessel and bears the inscription DIVITIE (wealth). Europe, bearing sword and shield, is characterised by the word BELLUM (war). Africa, meanwhile, is portrayed contemplatively, holding an open book on which is inscribed the word SCIENTIA (knowledge).

We find, here, a correction of perspective useful in the context of claims made in the European sphere, in a certain kind of political discourse, to perennial cultural supremacy, as if such a thing belonged to our continent by some sort of monopoly.

Restoration

What is the relationships between an original and a copy? In the light of Genesis 1,27, ‘God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him’, this problem is urgently relevant to every Christian. Athanasius, in his treatise On the Incarnation of the Word, developed it explicitly in terms of an artist’s work to restore a painting: ‘For as, when the likeness painted on a panel has been effaced by stains from without, he whose likeness it is must come once more to enable the portrait to be renewed on the same wood: for, for the sake of his picture, even the mere wood on which it is painted is not thrown away, but the outline is renewed upon it’. This enthralling documentary on the restoration of the Mona Lisa of the Prado is of more than just art-historical interest. It provides a parable of an existential pursuit of authenticity. It shows that a true copy is not a dead re-production, but a creation in its own right, possessing integrity. This applies to the works of a painter of genius. How much more must it apply to the works of the Author of Beauty?

Consultancy

Consultancy is a key function in our society. Enterprises large and small invest huge sums in it. The advisability of counsel is evident. St Benedict affirms, in chapter 3, ‘Do everything with counsel and having so done you will not repent’. Anyone who has exercised government knows what he means. There are times, though, when consultancy – weighing up options – is no good, when we have to abide by principles. We commemorate the martyrdom of Cyprian of Carthage. When arrested in 258, he was urged to perform the civic ritual the emperor required: a brief visit to the city hall, a little bit of incense strategically placed, and that would be that. Cyprian said no: to obey would, to his way of thinking, be blasphemy. The imperial proconsul was shocked. Taking Cyprian aside, he said, Consule tibi – that is, ‘Exercise consultancy’. Cyprian retorted: ‘In a matter so just, there is no consultancy to be had’, In re tam iusta nulla est consultatio. Sometimes there’s a limit to what consultancy can achieve. What matters then is simply to tell truth from falsehood, and to opt for truth.

Compassion

The requests put on our lips by the liturgy today, on the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows, are enormous. In the collect, ‘grant that your Church, participating with the Virgin Mary in the Passion of Christ, may merit a share in his Resurrection’; in the prayer after communion, ‘we humbly ask, O Lord, that […] we may complete in ourselves for the Church’s sake what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ’. These aren’t just words. They are pointers to the core of the Christian condition, where to be ‘passive’ is not to be inactive; on the contrary, incorporation into the Passion is the highest form of action, the presupposition for meaningful, effective Christian agency. We contemplate this truth in the ineffable compassion of Mary. Concepts fail to render its intensity. Music can hint at it, nowhere perhaps less inadequately than in Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. This version with Mirella Freni and Teresa Berganza is to my mind unsurpassed. Both singers are at the peak of their powers. But there is more than just virtuosity at work. Their mature voices enable the maternal mystery to be voiced with singular power.

Chrysostom

John Chrysostom is not a universally lovable saint like Polycarp or Francis of Sales. He was a preacher and teacher of genius; his fortitude was proverbial. Each year I am struck by the reference, in today’s collect, to ‘his astounding eloquence and his forbearance in persecution’. At the same time, Chrysostom had many rough edges. Some of his utterances can to this day startle us with their force, even violence.

He reminds us that genuine communion must be a function of truth, and that truth, more often than not, is something that has to be striven for.

The foundation of our oneness in Christ in the Church is radical authenticity. This requires us to be ready to denounce whatever in and around us is inauthentic, an obstacle rather than a help to the pursuit of genuine discipleship.

Like the Ore of Bells

There’s a tendency abroad to deprive the Church of her definite article, her capital letter, her personhood. What’s left, the task of ‘constructing church’ is a bit like ‘studying maths’, an exercise in human ingenuity. What a contrast in Gertrud von Le Fort’s Hymns to the Church: ‘Your servants bear ageless ornaments, your language is like bell-metal ore. /Your prayers resemble millennial oaks, your Psalms have the breath of the seas. /Your teaching is like a fastness on unassailable hills. /When you receive vows, they resound to the end of time; when you bless, you build mansions in heaven. /Your consecrations are like great signs of fire on human foreheads, no one can put them out. /The measure of your faithfulness is not the faith of men, the measure of your years encompasses no autumn. /You are like enduring fire above whirling ash! /You are like a tower in the midst of tearing waters! /That is why your silence is deep when days are loud; at eventime they will nonetheless fall upon your mercy. /You are the one who prays upon every tomb! /Where today gardens bloom there’ll be a wilderness tomorrow; where a people dwells at dawn, there is ruin at night. /You are the sole sign on earth of what is eternal; all that is not remoulded by you, is transmuted by death.’

Faithfulness

Queen Elizabeth II lived a life admirable in so many ways that the encomia pouring out on her death yesterday, on the feast of Mary’s Nativity, are inexhaustible. What strikes me especially, though, is this: one person’s radical fidelity to her task and station lent stability to the lives of countless others. Fidelity can take many forms. Who knows what awaits us? Important is the heart’s stability, translated into embodied living. I recently came upon this noble prayer formulated by John Paul II on his 65th birthday: ‘If one day illness touches my mind and clouds it, I do surrender to You even now, with [a] devotion that will later be continued in silent adoration. If one day I were to lie down and remain unconscious for long, it is my desire that every hour I am given to experience this be an uninterrupted thanksgiving, and that my ultimate breath be also a breath of love. Then, at such a moment, my soul, guided by the hand of Mary, will face you in order to sing your glory forever. Amen.’

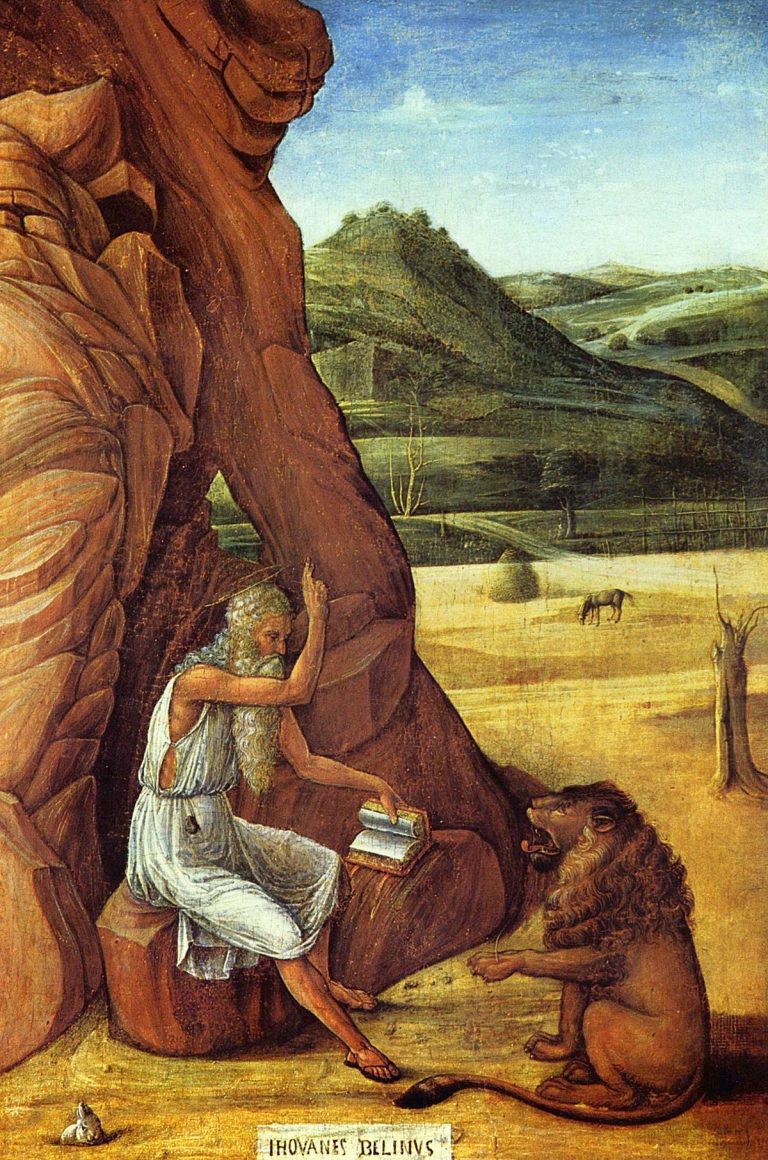

Man and Beast

When Anthony the Great, in the final stage of his long life, retired to the Inner Mountain, he was bothered by beasts that dug up his vegetable patch. He addressed them graciously (χαριέντως), saying, ‘Why are you doing me harm, since I do no harm to you?’ From then on, he and they lived together in peace. The restoration of harmony with the animal kingdom is a Leitmotif in ascetic literature, a sign of return to graced innocence, an indication of holiness. We are, as a generation, at the opposite end of the spectrum. A review of recent literature provides statistics that show how far our exploitation of animals has gone: ‘Spain’s porkers, nearly as numerous as its people, provide enough manure annually to fill the Barcelona football stadium 23 times over’; ‘We raise 66 billion chickens a year, eight for every human, almost all of them in terrible conditions’. The cinema is mobilised to open our eyes. I have been touched by Gunda and Cow. Both are beautiful. Neither is sentimental. Effectively these films reveal the otherness of animals, reminding us that the antiseptic, plastic-wrapped meat in supermarket fridges was once alive – and that all life deserves to be regarded with reverence.

Stepping out of Fear

In Scripture, a consequence of sin – which is a state of disorientation – is the experience of fearing where there is no fear (cf. Ps 53:5). The process of conversion involves the shedding of irrational anxiety. Sometimes, though, we’ve objective reasons to fear. This was the case with Judah in Jeremiah’s day, lending force to the Lord’s oracle, spoken through the prophet: ‘Do not fear the king of Babylon, of whom you are afraid; do not fear him, says the Lord’ (42:11). God does not tell the people their fear is groundless. He asks them to acknowledge it at a natural level, then to go beyond it in a spirit of faith. We often feel guilty about fear, trying either to suppress or dissimilate it. So it gains a deeper foothold. To say instead, ‘This is frightening, I am frightened’, can confer unexpected freedom. It grounds us in the real. To opt for the real is to aspire to truth. The truth, even when hard, liberates, opening us to the grace of courage.

אַל־תִּֽירְא֗וּ מִפְּנֵי֙ מֶ֣לֶךְ בָּבֶ֔ל אֲשֶׁר־אַתֶּ֥ם יְרֵאִ֖ים מִפָּנָ֑יו אַל־תִּֽירְא֤וּ מִמֶּ֙נּוּ֙ נְאֻם־יְהֹוָ֔ה כִּֽי־אִתְּכֶ֣ם אָ֔נִי לְהוֹשִׁ֧יעַ אֶתְכֶ֛ם וּלְהַצִּ֥יל אֶתְכֶ֖ם מִיָּדֽוֹ

Metaphysical scandal

It is often assumed that what puts the Church at odds with contemporary society is its ethical teaching. Many cry out for change in this area. Quite apart from the merit of considering what might be a Catholic response to particular, perhaps new problems in ethics (something each age is called upon to do), I consider the assumption false. I do not think the principal skandalon is ethical. I think it is metaphysical.

The holiness of God! The splendour of his glory, made manifest in Christ through infinitely gracious condescension! These core realities, which to the founders of Cîteaux were axiomatic, seem strange to an age whose outlook is wholly horizontal. We are children of that age. Of this we must ever be aware.

From a Letter to the Order.

Enough to Say Yes

‘For me and for each one of you, when God called us to specific stations in life, He revealed very little: the basic call, the bare bones. His invitation didn’t include a biography and a script, and so it called for faith and trust, our hand in God’s. No rose garden, only that whatever the garden, Eden or Gethsemane, He would be there faithful through all our infidelities. It’s true of every vowed existence, husband and wife, priest or religious, the law, dance, music or medicine, commerce or the State house. It’s true of the powerful and the powerless. God tells us only enough for us to say yes.’

With these words the Assuptionist Fr Philip Bonvouloir (1929-2012) offered friends a retrospect of his own experience. In it I dare say many of us will recognise our own.

Ecology

To signpost what is effectively a rubbish dump as an ‘ecological isle’ requires some semantic acrobatics.

To sort waste is admirable, but is still just a way of storing it. The work of purification is a separate process, happening elsewhere, with an energy proper to it.

Really ecological would be the non-generation of junk, so as not to have to get rid of it.

The logic can be transferred, mutatis mutandis, to the inner life. There too we must beware of supposing that merely labelling and sorting amounts to cleansing.

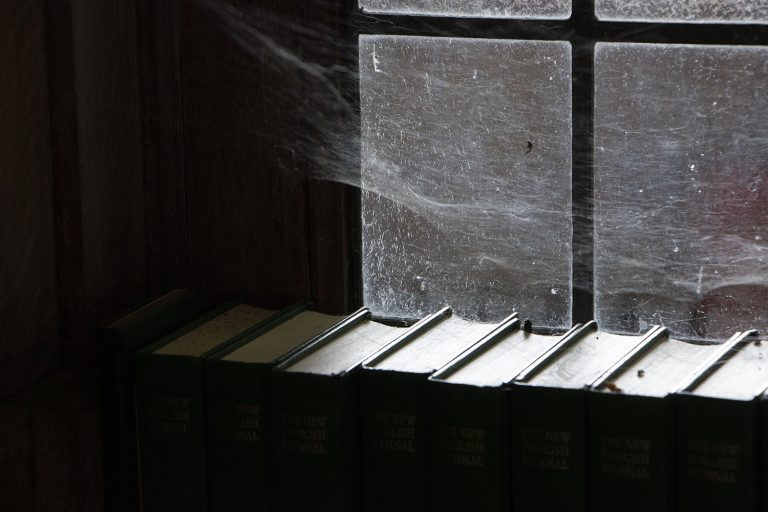

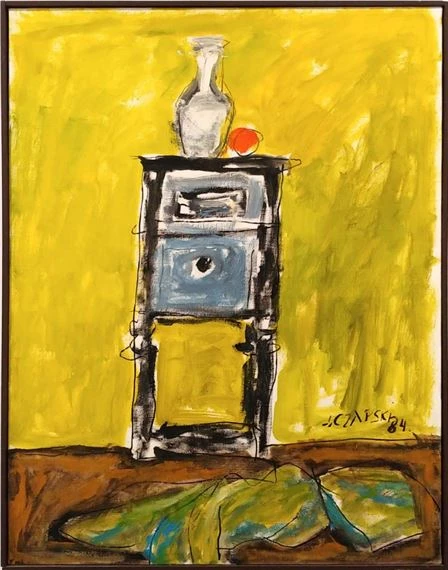

Practising Sight

Contemplative life is grounded in an ability to see. Contemplation is grace, of course, but grace, as ever, builds on nature, so we must exercise our faculty of sight. That’s something we all can do. In fact, if we fail to foster an ability to see and distinguish colour, the world around us increasingly appears monochrome. Czapski once noted:

‘Dusk already. Work once again, fresh and sure. Sure, in what way? In the way I control myself, objectify, expand the range of my sense of colour which, when I don’t work, is impoverished. The routine? Could you call this routine, this secular technique that opens a universe of happy, pictorial experiences before me? This slow pace couldn’t be called vision, it’s more like an apprenticeship of looking.’

Daybreak

Hans Ulrich Treichel’s novel Daybreak is effectively a pietà in prose. An elderly woman cradles her middle-aged son, dead after long illness, and at last feels free to express to herself – and to us – elements of the drama that has framed her life, which only in appearance has been ordinary (what is ordinary?) and banal.

How litte we know of one another! How limited is our notion of what others may be carrying, what heroism they may be called upon to exercise simply to rise in the morning!

‘Have we not passed along a steep mountain pass?’ asks the narratrix towards the end of her story. Indeed she has. And she has enabled the reader to get a sense of the risks run at such altitude.

Hunting the Pluck

This Heaney poem makes me think of John 7:38. It is one thing to carry a spring of water, another to find it.

Cut from the green hedge a forked hazel stick

That he held tightly by the arms of the V:

Circling the terrain, hunting the pluck

Of water, nervous, but professionally

Unfussed. The pluck came sharp as a sting.

The rod jerked with precise convulsions,

Spring water suddenly broadcasting

Through a green hazel its secret stations.

The bystanders would ask to have a try.

He handed them the rod without a word.

It lay dead in their grasp till, nonchalantly,

He gripped expectant wrists. The hazel stirred.

Far and Wide

In 1900, five years before Norway regained sovereignty, parliament passed a motion to grant 12,000 kroner towards the publication of Heimskringla in both established forms of the Norwegian tongue, ‘so that the book might reach far and wide, being affordable’. The notion that a nation in search of corporate identity would gain from engaging with its founding narratives was taken for granted and subsidised.

This provides food for thought in a cultural context marked by wilful amnesia. We readily live and speak as if the past were mere overweight, prospect all that mattered. And we’re surprised that we’ve trouble coming up with a sharable account of who we are, what we’re about? Never, perhaps, has there been a time in which the practice of careful remembrance was more necessary, indeed a civic (and ecclesial) duty.

Thanks

It was once common for votive plaques to be fitted in churches in thanksgiving for graces received. An object might take the place of a plaque: a crutch showing that the owner had no further use for it, a photograph of a long-awaited child.

An essential passage in the Gospel is the one in which Jesus, between Samaria and Galilee, asks the cleansed leper come to thank him: ‘Were not ten cleansed? Where are the nine?’ (Lk 17:17).

I love this unpretentious ensemble. Loud gestures are not always needed to give thanks. Sometimes a pine cone says it all.

What matters is the consciousness of having been graced, then the capacity to respond graciously.

Wind-Whirls

This morning I stood at a window holding a bowl of hot tea while watching a swallow circling a pond into which, every third round or so, it shot like a bullet. The window was shut, I couldn’t hear the swallow. But I could see its jubilation.

This afternoon I saw a paraglider under a billowing, bright yellow sail perform gracious wind-whirls, all the lovelier for being wholly gratuitous.

It struck me that the two were doing the same thing: making being explicit and delighting in it. What a splendid urge all creatures have to enact that line in Hopkins’s poem, almost a confession: ‘What I do is me, for that I came’. Yet how much distracts us from it. How easily we surrender to unselving and so accumulate, instead of joy, dispiriting sadness.

Ave Crux

The saint we honour as Rose of Lima was born in Peru, to Spanish parents, in 1586, 23 years after the closure of the Council of Trent, which energised global Catholicism. In Rose’s life, this energy was manifest in strong dedication to care for the poor, which brings her close to the aspiration of contemporary Christianity. We may, by contrast, feel estranged by her life of mortification. For Rose, the Passion of Christ was not a subject for meditation. It was the vital atmosphere within which her existence unfolded. Her attachment to the Cross was radical. This is an aspect of the Christian condition that, today, we tend to forget somewhat. God, says St Paul in today’s Mass reading, calls us ‘to share the glory of our Lord Jesus Christ’. Now, that glory was supremely manifest on Calvary. To recognise this fact is not to yield to a morbid religiosity. It is to read the Gospel honestly, recognising our need for redemption and affirming the effective truth of the refrain the Church sings on Good Friday: ‘By the wood of the Cross joy entered the whole world.’ Thereby, not otherwise.

St Bernard

In a sermon, St Bernard or Clairvaux likens the Christian’s life in this world to a man who carries a flickering flame through a long, stormy night. The wind blows, the rain lashes down. To keep his flame from going out, he cups it with both hands, focusing all his attention on keeping it safe as he makes slow progress towards the Father’s house. What keeps his courage up is the certainty that he will, as long as he is faithful, arrive there one day. ‘And in that house not made with hands’, Bernard says, ‘there is nothing to fear. No enemy enters that house. No friend leaves it.’ The last remark is characteristic. St Bernard had a life-long charism for friendship. He knew that, in order to serve God, we have need of one another, and that this fellowship of truth-seeking hearts is life’s sweetest gift.