St Bernard

In a sermon, St Bernard or Clairvaux likens the Christian’s life in this world to a man who carries a flickering flame through a long, stormy night. The wind blows, the rain lashes down. To keep his flame from going out, he cups it with both hands, focusing all his attention on keeping it safe as he makes slow progress towards the Father’s house. What keeps his courage up is the certainty that he will, as long as he is faithful, arrive there one day. ‘And in that house not made with hands’, Bernard says, ‘there is nothing to fear. No enemy enters that house. No friend leaves it.’ The last remark is characteristic. St Bernard had a life-long charism for friendship. He knew that, in order to serve God, we have need of one another, and that this fellowship of truth-seeking hearts is life’s sweetest gift.

Quixote in Odessa

In his latest dispatch from Ukraine, published today in Dag og Tid, Andrej Kurkov reports that Minkus’s Don Quixote was performed, this week, at the Odessa Opera to a full house. To stage a ballet in the midst of war is an act of defiance, upholding the attainments of the human spirit in the face of brute aggression. One could interpret the choice of repertoire as high sarcasm. For this enterprise is not ‘quixotic’; it is bound to prevail. The spirit always does, in the long term. Last week, Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk remarked, continuing his exceptional wartime catechesis: ‘the cornerstone of any society is respect for the dignity of the human person and the sanctity of human life, from conception to natural death. Because it is from the dignity of a person that all other rights and responsibilities of a person derive.’ To be determined to counter ugliness with beauty is to display what dignity is, and so to spread hope far abroad.

Grandeur of Time

A quarter-century ago I heard Olivier Clément speak unforgettably of the virtue of slowness. The world has speeded up a lot since then. We need to hear voices that remind us of the craziness of constant acceleration. Like that of Marie Noël, who in 1946 noted: ‘Here, each evening, there comes a splendid moment: the homecoming of the oxen with the great cartloads of sheaves towering over them […], they appear, slow and majestic, to come straight out of eternity. Maybe Boaz saw their like. And maybe that is the true rhythm of work, the one God devised for man, that noble gait, that powerful, unhasting tread. Perhaps our Cathedrals were conceived and built without hurry or fret, and with the steady calm of mind and hands and only the vigorous effort measured to the day’s need. Perhaps all human labour, be it of soul or body, requires for its beauty something of the grandeur of time.’ From a precious Essay in Meaning translated by Pauline Matarasso, p. 239.

Redressing Loss

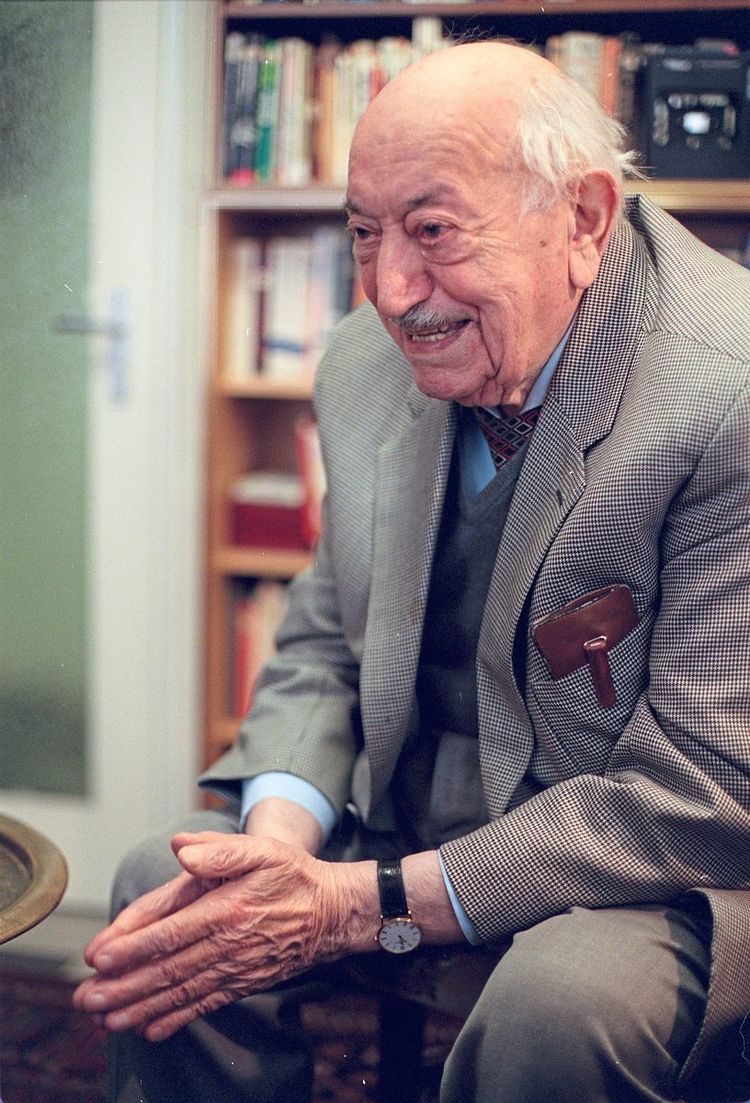

Ever since I first read Simon Wiesenthal’s book Recht, nicht Rache (Justice, not Revenge), the legacy of this nobly tireless yet unbitter maintainer of remembrance has marked me deeply. In a documentary now a few years old, Sir Ben Kingsley, who played Wiesenthal in the feature Murderers Among Us, speaks about his first encounter with a man he had to get to know, so to speak, from within. What struck him above all — ‘it has never left me’ — was the way in which Wiesenthal would spontaneously draw his hand across his face in a gesture of contained despair: ‘I have never seen anyone else physically embody a whole generation of grief in one gesture. He manages to tap into the collective grief and the understanding of grief in all of us, whatever our history. This I think is tremendously healing. Because if you cannot grieve over loss, you cannot begin to redress that loss and repair the damage done.’ Kingsley stresses, though, that there was more to Wiesenthal than the incarnation of grief: ‘As well as weeping all of his tears, he was a man capable of laughing all of his laughter.’

Maybe

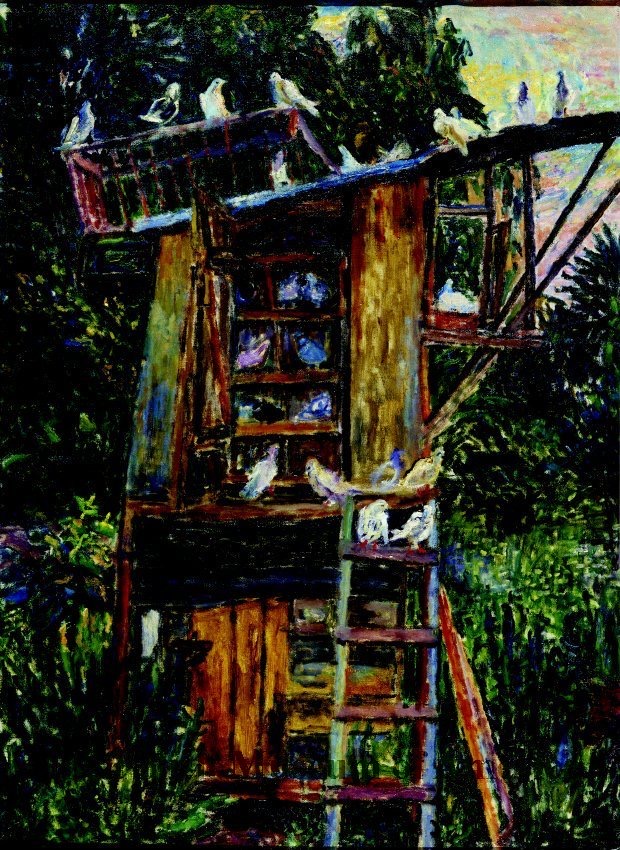

In 1949, 53 years old, having recorded his account of a war during which he’d endured and witnessed terrible things, faced now with the suffocation of Poland, Józef Czapski asked himself if it was still possible to paint. Should he paint, a new form of expression was called for — but was the pursuit of art even moral? He wrote to Hering: ‘All I want to do now is to disconnect myself from other painters, from the Louvre, from the methods, and to use all my passions to gnaw their way into some painting of mine. Maybe a painting of an old Jewish woman in a train or standing at the Otwock station is closer to my heart today than the most scrumptious Parisian ideas. My painting really seems to have no use for Paris. I have one good friend here who continues to blast me harshly for not painting. Even though I tell him, “But the sky is falling, and you want me to sit and paint?” And he says, “Maybe the sky is falling because you and the others have stopped painting.”‘ (In Karpeles, p. 268).

Age-Old Battle

At the end of 1938, Edith Stein was moved from her monastery in Cologne to the Carmel of Echt in Holland. Her superiors hoped that, there, she would be less exposed to Nazi persecution. She had, however, as a Jew, to report in person to the occupying forces. Turning up at HQ in Maastricht, she was struck by its ordinariness. It was just a busy office like any other busy office, full of girls with typewriters, their minds half on the work in hand, half on their evening engagement. How deceptively innocuous is the bureaucracy of evil! Edith’s discomfort grew while she waited. It reached its pitch when she was summoned to appear before officers of the Gestapo, whose standard greeting was, ‘Heil Hitler!’ Edith promptly declared, ‘Praised be Jesus Christ!’ She later told her prioress she knew this response could be perceived as an outright provocation, but she could do nothing else. Then and there, she said, she was intensely conscious of being caught up in the age-old battle between Jesus and Lucifer. Each day’s task is to acquire wisdom to recognise the terms of this battle, courage to step forward when we are called, grace to let Jesus work his victory through us. His strength is made perfect in our weakness if only we place that weakness unreservedly at his disposal.

Beyond the Trivial

In an insightful review of a book I think I’m unlikely to read, Rowan William provides a throw-away, elegant definition of poetry. ‘Poetry’, he says, ‘is language so constructed that it lets us see beyond the trivial, exploitative, weaponized uses of words that are deafeningly present around us.’

The word ‘weaponised’ is unexpected, but it is spot on. It recalls me to this morning’s Vigils reading from the Book of Hosea: ‘Provide yourself with words and come back to the Lord’ (14:2).

It is a great and urgent civilising task to redeem words that have been taken hostage for violent purposes, to liberate them and enable them to metamorphose into praise, the highest, noblest form of free expression.

Wooing Humanity

‘The faith of God in us makes, every now and then, one of us come true. And then a heart is rhymed to the very beat of God, a mind to truth, and a mouth to gospel, wooing the matter of humanity to God.’ I find these lines, written by Fr Simon Tugwell, printed as an epigraph to a fine new edition of the Dominican Libellus Precum published by the English Province of the Order last year. Fr Tugwell continues: ‘Such a man was Dominic, messenger of God’s love, a carrier of his infinite pain and hope, a hurricane and a haven, hurling torrents of peace through the civilised corridors of comfortable half-truths, of plump correctness and wizened zeal; to dwellers in ancient darkness long familiar, a disturbing possibility of day.’

May it please God to raise up men and women of such stature also now.

Rilke on Joy

‘These things have I spoken unto you’, says Christ in the Gospel, ‘that my joy might remain in you, and that your joy might be full’ (Jn 15:11). Joy, like peace, is a criterion of authenticity in spiritual discernment. It matters, then, to distinguish it clearly. On 31.01.1914 Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to Ilse Erdmann: ‘The reality of any joy in the world is indescribable; only in joy does creation take place (happiness, on the contrary, is only a promising, intelligible constellation of things already there); joy is a marvellous increasing of what exists, a pure addition out of nothingness. How superficially must happiness engage us, after all, if it can leave us time to think and worry about how long it will last. Joy is a moment, free of obligation, timeless from the beginning, not to be held but also not to be truly lost again, since under its impact our being is changed chemically, so to speak, and does not only, as may be the case with happiness, savour and enjoy itself in a new mixture.’

Růžičková

My main musical discovery this summer has been a recording released in 1972 of Zuzana Růžičková (1927-2017) and Josef Suk (1929-2011) playing Bach’s sonatas for harpsichord and violin. Suk and Růžičková introduce the listener into a wholly new, often surprising sonorous universe. Their interpretation is marked by intelligence, rigour, and (to use that unfashionable word) virility. Quiet passages resound with an almost unbearable tenderness free of appeal to superficial sentiment. The two communicate this music as an essential statement. They play Bach as if their lives depended on it.

When you read up a little about Růžičková, you find that hers literally did, in extreme circumstances. Her existence was deeply marked by Europe’s twentieth-century traumas, yet she seems to have been without bitterness. I recommend Peter Getzels’ cinematic portrait of this remarkable musician, available here – or on Medici.

Ashamed of our Face

In her fine 1997 series on the history of painting, Sister Wendy Beckett marvelled before the murals of Lascaux: ‘All these animals are beautiful. And centuries ago, when there was room on earth for all of us, how humankind must have yearned to be strong and beautiful, free, innocent — all the things that they were not, and we are not; and perhaps that’s why they made these images secretly in the earth, to honour the animals?’ Before the same murals, three decades earlier, Zbigniew Herbert had wondered at the comparatively inadequate, often disguised representation of man: ‘Man destroyed the order of nature by his thought and labour. He craved a new discipline through a sequence of self-imposed prohibitions. He was ashamed of his face, a visible sign of difference. He often wore masks, animal masks, as if trying to appease his own treason. When he wanted to appear graceful and strong, he became a beast. He returned to his origins lovingly submerged in the warm womb of nature.’ I wonder: are we not weirdly witnessing, now, a similar kind of retreat behind a similar kind of mask, inspired by a similar kind of shame?

Never More Bishop

What’s a bishop for? The list of answers is long. Ideally he should be all things to all people! Still, something basic is expressed in this account that features in Martin Mosebach’s important book, The 21.

‘In Wadi-Natrum, in one of the ancient monasteries which had grown into new greatness, it was announced to me that the very elderly Abbot, also a Bishop, would appear. A small door opened, and there was the old man, his gaze dreamingly absent. He stood up straight, but was visibly already resident in another world, with staff and cross in hand. Could he sense the lips that touched the back of his hand? His gestures of blessing were faint; still, he must have been conscious of the presence of the faithful. Never was he more a bishop than just then, nothing but the vessel of a more exalted will.’

Not Ready-Made

Sigrid Undset wrote of St Olav, patron saint of our diocese and country: ‘Saint Olav was the seed our Lord chose to sow in Norway’s earth because it was well suited to the weather here and to the quality of the soil.’ What makes his story so compelling is the fact that we can follow, step by step, the work of grace in his life. Olav was not a ready-made saint; he began adult life as a viking mercenary. Though through his encounter with Christ in the Church, through decisive sojourns in Rouen and Kyiv, then his final, dramatic return to Norway, where he died a martyr, supernatural light gradually took hold of him and suffused him, radiant in his body even after death. The feast of St Olav is kept on 29 July. Should you wish to follow our triduum of celebrations, beginning this evening, you can find access here. A good account of St Olav’s life is available here.

Prayer & Poetry

At vespers tonight, the feast of Sts Joachim and Anne, I was struck by the Magnificat antiphon. The text is familiar, but it was as if I read it for the first time: ‘Inclita stirps Iesse virgam produxit amoenam, de qua processit flos miro plenus odore’ (The glorious stem of Jesse brought forth a lovely shoot from which proceeded a flower replete with wondrous scent’). The repeated dactyls produce a pleasing rhythm moving towards the restful syllable ‘flos’, which is a way of conveying, without clunky commentary, that the feast is not primarily about the individuals named but about the fruit of their union, whose whole existence was oriented towards Christ. The noun ‘virga’ (‘shoot’) suggests ‘virgo’ (virgin). The image used to describe her Child indicates the important Pauline theme of Christ’s fragrance (2 Cor 2:15). More could be said about the choice of words. These riches are contained in a single, humble line. Why did it impress me so? Because it is so unlike many newer liturgical prayers, which read like announcements in morning assembly. Is one reason behind the trouble we have integrating our liturgical past a loss of poetry?

Following Jesus

An existential question in the middle of urban traffic.

Sorrow and Joy

The liturgy honours St Mary Magdalene, first witness to the resurrection, with the title Apostle to the Apostles. What equipped her for this? The perseverance and courage that enabled her, at a point when all her hopes were shattered, she who had so often been let down, just to remain, wait, and weep. She did not run away from grief. She did not seek distraction from it. Nor did she lock herself within it, indulgently. She touched its core, simply and deeply, and was thus prepared to recognise the presence she sought not in front of her (where she had expected it) but behind her, where she could have sworn it must be someone else’s.

It is hard to sustain sorrow. But sometimes there is no other way to encounter joy.

Communion

In a beautiful, elegiac tract, Yoshida Kenkō (c.1283-c.1352) reflects on the transience of earthly things, counselling detachment. He take delight, though, in encounters. ‘What happiness to sit in intimate conversation with someone of like mind, warmed by candid discussion of the amusing and fleeting ways of this world … but such a friend is hard to find, and instead you sit there doing your best to fit in with whatever the other is saying, feeling deeply alone.’

Even in such cases there is a remedy within everyone’s reach: ‘It is a most wonderful comfort to sit alone beneath a lamp, book spread before you, and commune with someone from the past whom you have never met’ — yet nonetheless do meet somehow through the medium of the book.

Children

With characteristic lucidity, Eivor Oftestad analyses a recent documentary on surrogate parenthood. We assume we know what the parental-filial social contract consists in. She helpfully highlights the extent to which it is conditioned by changing circumstances:

‘Our understanding of what a child is cannot be taken for granted. It reflects, at any time, conditions and notions prevalent in cultural paradigms. An agrarian society understood the begetting of children as generation. The industrial society was inclined to regard it as production. Today, in a consumerist society that hardly permits experiences of deferred need, it is increasingly seen in terms of acquisition – and everything, as we know, can be acquired if we pay for it.’

Do we think in terms of being given children or of getting them? The question really matters.

Two Ways

In today’s Vigils reading, St Ignatius of Antioch (ad Magn. 1-5) develops a motif typical of early Christian writings. It is the image, rooted in Deuteronomy 30:19, of the two ways between which each human being must choose. ‘All things have an end, and two things, life and death, are side by side set before us, and each man will go to his own place. Just as there are two coinages, one of God and the other of the world, each with its own image, so unbelievers bear the image of this world, and those who have faith with love bear the image of God the Father through Jesus Christ. Unless we are ready through his power to die in the likeness of his passion, his life is not in us.’

Living as we are in a world of endlessly blurred boundaries, this perspective challenges us. It is a salutary challenge. We need the testimony of brave women and men who choose life. It isn’t an easy option; it will, as Ignatius says, bear the mark of Christ’s passion. But it will be a function of truth, and the truth sets us free.

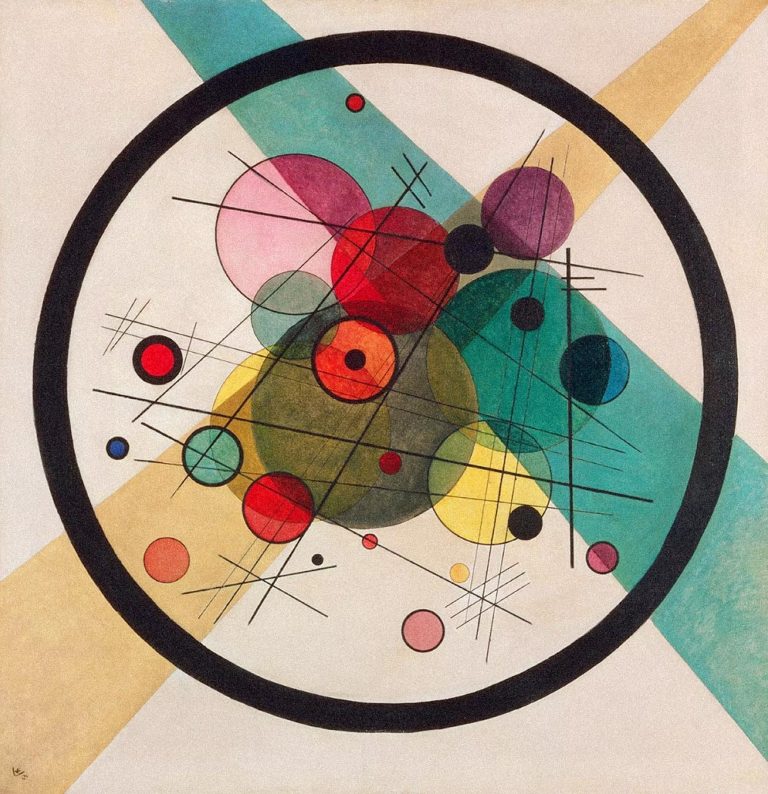

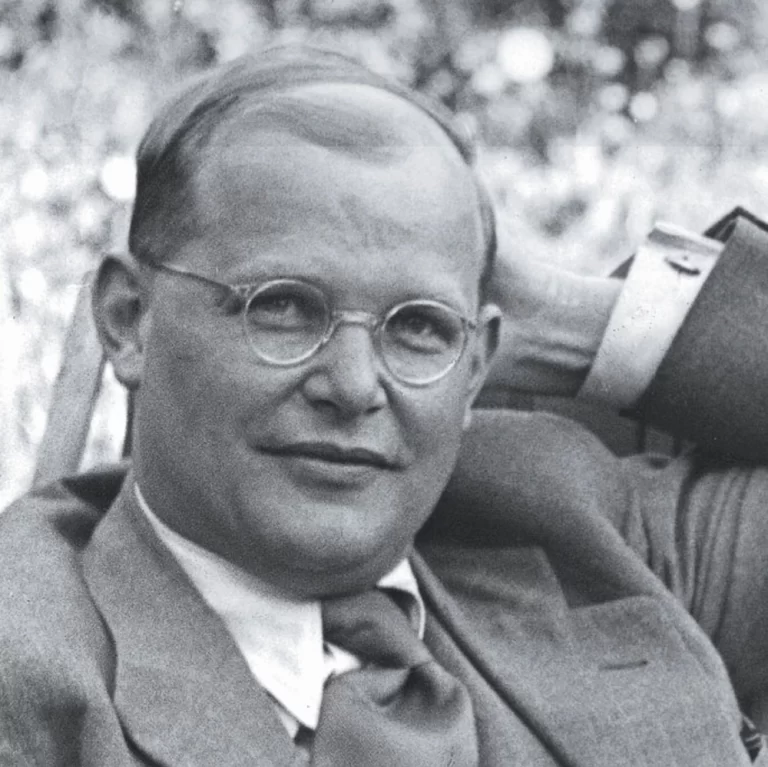

Stupidity

I have long pondered a statement made by Bonhoeffer in Resistance and Resignation. At first I thought it was rhetorical hyperbole; now I no longer think so. ‘Stupidity is a more dangerous foe to the good than wickedness. One can protest against evil. Evil can be exposed. It can even, in extremities, be fought against with violent means. Evil always carries the seed of its own decomposition and at any rate calls forth unease in human beings. Against stupidity we are defenceless. Here we can do nothing whether by protest or by force. Reasoning has no effect. Objective facts that go against the grain of one’s prejudice are dismissed – in such cases the stupid person reveals critical faculties. If the facts simply can’t be overlooked, they will be sidelined as singular cases void of consequence. In acting thus, the stupid – in contrast to the evil – person is wholly pleased with him or herself; indeed he or she becomes dangerous, easily provoked to attack. Greater care, then, is called for in confronting stupidity than in confronting wickedness.’

Of course, the stupidity Bonhoeffer speaks of is not incompatible with considerable intelligence. What’s lacking is prudence.

Usefulness

I know nothing of the surgeon Thomas Prickett beyond what is recorded on this plaque in a thirteenth-century church on the Isle of Wight. But what is stated there is enough.

I’d say one can be counted blessed who is remembered as having lived ‘a life of extensive usefulness’ to others. Indeed we could do with a revival, Europewide, of aspirations to public service. Mr Prickett not only lived well. He also died well, ‘with piety and resignation’. And this he learnt to do in no more than thirty years of existence.

He must have been a good man. May he rest in peace.

Vacation

Coram Fratribus will take a holiday for a couple of weeks.

Thank you for your interest in the site!

I wish you a pleasant summer.

+fr Erik

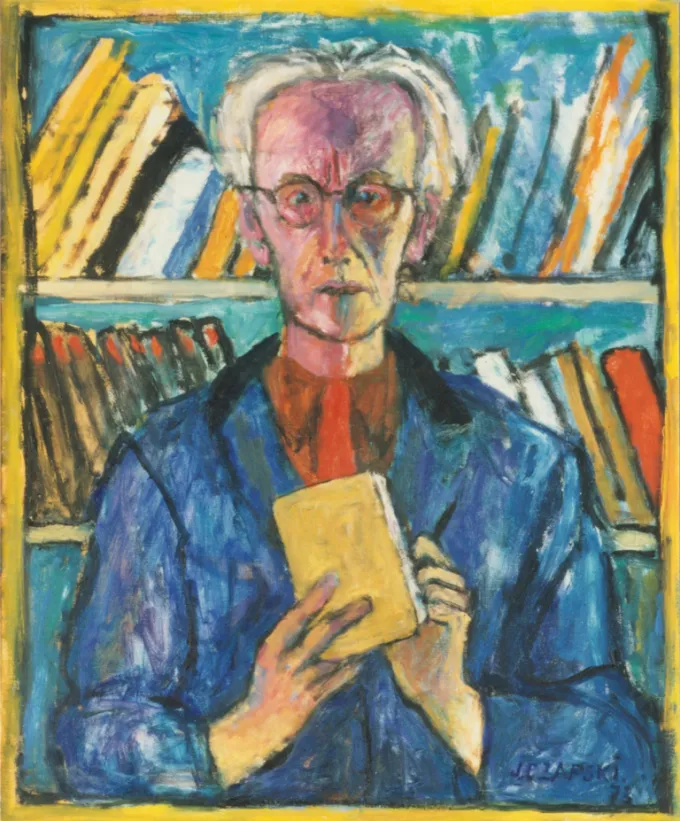

Czapski

Having visited the Józef Czapski Pavilion in Cracow last September, I was keen to learn more about this extraordinary writer and painter. Czapski’s little book on Proust, Lost Time, is a marvel: the text came into being as lectures given to fellow inmates in a Soviet prison camp. Eric Karpeles’ life of Czapski, Almost Nothing, is also highly readable. A fine portrait not only of a man, but of an age.

A contribution to The Tablet’s recommendations for Summer Reading.

Spirituality

Last week, Abbess Christiana Reemts offered this compact reflection:

‘Earlier, people would say, “I don’t believe in God” or, “I am an atheist”. Now we’re more likely to hear, “Spirituality matters a great deal to me.” What is intended is often the same.’

Transmission

It is a standing joke in Italy that many of the country’s structures don’t work. What does work is the effective transmission of culture. One stumbles across ancient remnants everywhere, of course. But that isn’t all. Italians remain conscious of being heirs to a great civilisation. This heritage is taught in school, discussed in the media, fostered in excellent museums. It isn’t just about looking back to a glorious past. It’s about positioning oneself in the present. When I walked past this newsagent’s window one day last week, a copy of Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War was on display. I enjoyed seeing it. When I went back the next day to photograph it, it was gone: someone had bought it. But a book about Athens and Sparta was there instead, in among the romantic novels and autobiographies of athletes. With Europe in a state of anxious transformation, really under threat, more of us could benefit from revisiting the foundations of our civilisation, reminding ourselves of the history and core meaning of notions like ‘freedom’, ‘democracy’, ‘tyranny’, etc. We need to galvanise our sense of what is worth defending, and why.