Grace to Receive

The ordination of deacons concludes with the traditio evangelii. The bishop hands the newly ordained a book of the Gospel, then addresses to him this exhortation:

Receive the Gospel of Christ, whose herald you have become. Take care that you believe what you read, that you teach what you believe, and that you fashion your life according to what you teach.

A causal chain is indicated here. It absolutely presupposes the first element: Reading the Gospel as it is given us, not as we might like to rewrite it.

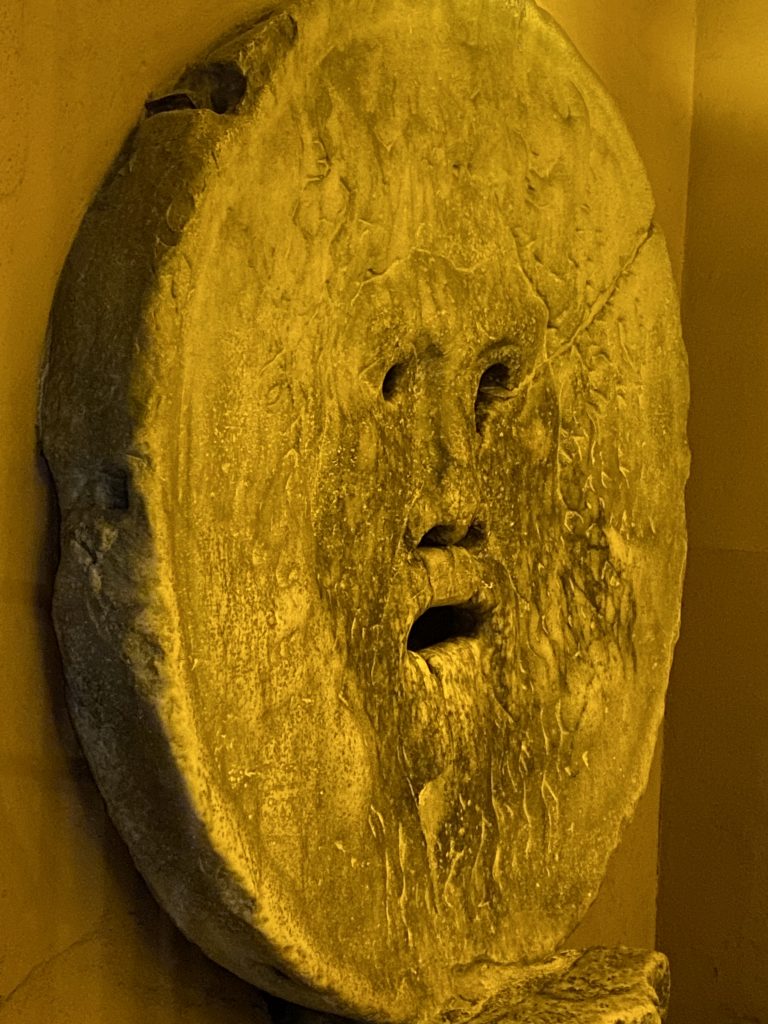

Mouth of Truth

The Bocca della verità outside Santa Maria in Cosmedin is one of Rome’s best known landmarks. It features significantly in that immortal film, Roman Holiday, but its history reaches back far beyond celluloid into the mists of history. The story goes that any liar who places a hand in its mouth will have it bitten off. In daylight, the round face looks pleasant enough. The legend attaching to it seems a bit of a joke. Illumined at night by a strange yellow light, the effect is different. The monument looks lunar, sinister, cruel. It makes me reflect that truth on its own, detached from virtue, can have an aspect that is vindictive and destructive. To be life-giving, truth must be suffused with humanitas, which to the ancients was a way of expressing ‘compassion’. The truth, said St Paul, must be enacted in love (Eph 4:15). Detached from love, it risk being marked by the the old titan’s features: an indiscreet, cold, incurious stare and a voracious mouth.

Anger

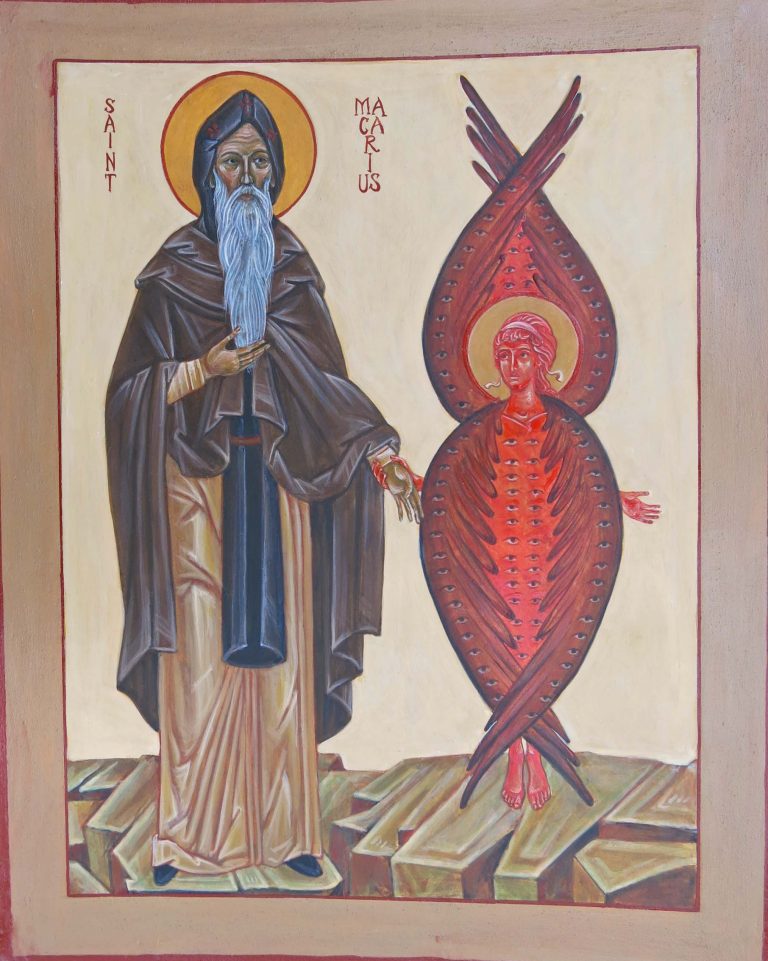

Friday’s terrible shooting in Oslo is yet another indication — as if we needed more — of the breakdown of conversation in our society. Culturally, the West is pulled in different directions. With certain tendencies we may be in deep disagreement. Yet to seek to annihilate difference, to point a gun (be it rhetorical) at those who embody difference, is perverse. It is time to recover the use of logos, reasoned speech. It is time to be on our guard against discourse sprung from anger. Macarius the Great said: ‘If while correcting another you are carried away by anger, you are feeding your own passion. Yet you mustn’t destroy yourself to save another.’ Today’s Gospel is relevant. Faced with the insult of a Samaritan village that refused to let Jesus in, James and John proposed to ‘call down fire from heaven to burn them up’. The Lord ‘turned and rebuked them’. An ancient Gospel manuscript adds the content of his rebuke: ‘You do not know what manner of spirit you are of; for the Son of Man came not to destroy men’s lives but to save them’ (Luke 9:51-5)

Pardon

No contribution to the World Meeting of Families has received more attention in the secular press (here, for instance) than that of Daniel and Leila Abdallah, a Maronite Australian couple. Their talk called forth a strong response in the aula, too. We all, thousands of us, rose to our feet in tribute to their testimony. The two spoke of pardon. They know more about its cost than most, having lost four children in a terrible accident caused by a drunk, drugged driver on 1 February 2020. The Abdallahs’ Christian response to their loss has had a massive impact in Australia, resulting in the institution of a National Day of Forgiveness. The work of grace in the couple’s life is palpable. Yet they insisted that pardon first of all requires a will to forgive. ‘Forgiveness’, said Leila, ‘is a choice you make’. Daniel added: ‘I had to forgive so that my family would not be imprisoned in the trauma of that night.’ It is precious to be reminded with such simplicity, such authority that no interior prison sentence needs to be final.

Light Struggle

Gigi De Palo and Anna Chiara Gambini spoke today of discovering, four years ago, that their newborn son, Giorgio Maria, had Down’s. There and then, in hospital, they looked at each other, said Gigi, ‘with complicity’, exchanging a glance in which the whole history of their love was contained. And embraced with joy the child given them. They spoke unsentimentally about the struggle it involves to raise a child gifted in this way, but it is, Anna Chiara insisted, a light struggle – ‘Una fatica leggera’. In objective terms it has weight, yet the heaviness is lifted by the love circulating between parents and child, and drawn forth in others. We were told about Giorgio Maria’s singular ability to enable others to respond to him with love. The presentation amounted to an empirical validation of Christ’s saying, ‘my yoke is easy and my burden is light’. The yokes and burdens we carry can seem overwhelmingly our own, yet they can become his, so eased and lightened, if we call his loving presence into them.

Reconciliation

This evening the World Meeting of Families began in Rome. What impressed me most was the testimony of Paul and Germaine Balenza, a couple from Congo, married since 1995. Twenty-six years into marriage, Germaine discovered that her husband, a public figure, had been unfaithful. ‘I felt’, she said, ‘that power had gone to his head, that he was no longer interested in me.’ She left him, and set about publicly shaming him on social media. It was a miserable time for both. With the help of a Catholic couple, Paul began to do serious work on himself. Germaine was drawn into the process. ‘We were able’, she says, ‘to tell each other hard truths, to empty our hearts of hatred and anger.’ Gradually, they resolved, in Christ’s name, to be reconciled. They assembled their families and asked forgiveness of their children; then, in church, they renewed their marriage vows. We sometimes place the ideal of a Christian family on such a pedestal that it seems to be unreachable – or even to vanish into the realm of fiction. Here, meanwhile, is a story that fits into a Biblical paradigm, where families as a norm are dysfunctional and for that reason display the work of grace palpably and credibly. Paul and Germaine remind us with authority that the world can begin anew even when all seems lost.

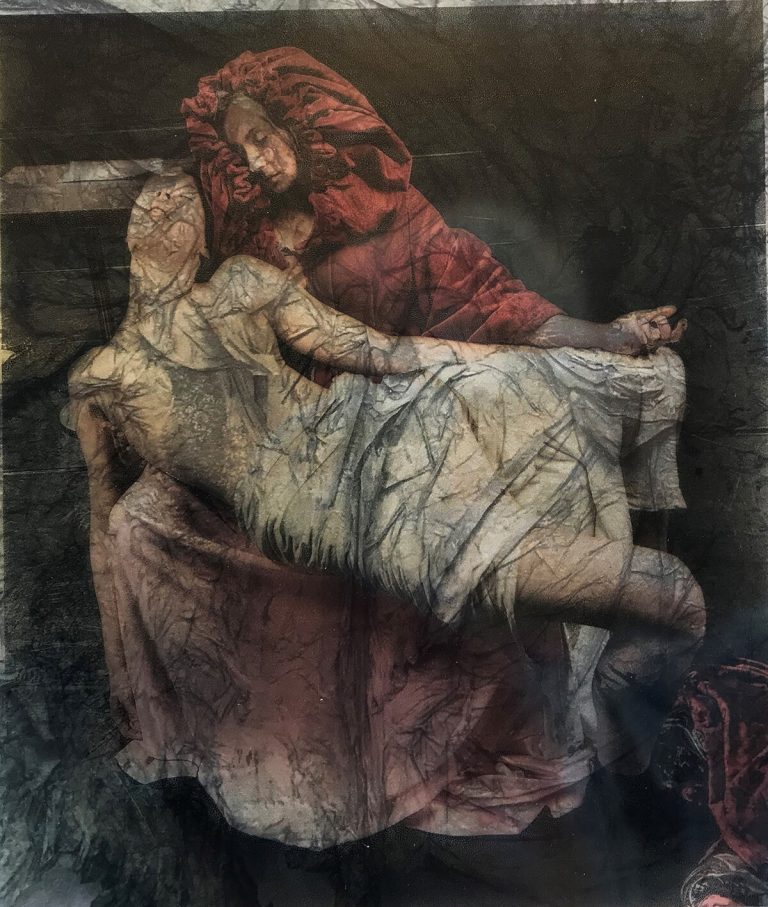

Never Confuse

I recently happened on a letter Mother Thekla (Sharf), nun of Whitby, wrote to an imaginary convert to Orthodoxy. It probes the self-seeking that can lie hidden in religious aspirations — and indicates remedies. ‘I have not been told why you are about to convert, but I assure you there is no point whatsoever if it is for negative reasons. Are you expecting a kind of earthly paradise with plenty of incense and the right kind of music? Do you expect to go straight to heaven if you cross yourself slowly, pompously and in the correct form from the right side? OR….. Have you faced Christ crucified?’ This, Mother Thekla insisted, is the crunch. It’s about resolving to believe, whatever happens, that Christ’s redemptive work makes sense. And to act on it. ‘That does not mean passive endurance, but it means constant vigilance, listening for what is demanded; and above all, love. Poor, old, sick, to our last breath, we can love. Not sentimental nonsense so often confused with love, but the love of sacrifice – inner crucifixion of greed, envy, pride. And never confuse love with sentimentality. And never confuse worship with affectation.’

The Rose

How can I see the world that surrounds me? Anyone who has considered the question knows the answer isn’t obvious. More than analyses, sometimes, we need testimonies, such as Maud Sumner’s in this brief poem:

Till the midnight hours

I sat up with a rose

To watch the rose.

Other flowers

Drowse and close

But the midnight rose

Then chiefly shows

Its wine-red powers —

Perfume so deep from the heart of the flower,

Beauty so sweet, that zero hour

Stands still,

A frill

Torn from the robe of eternity,

Holding all silence — holding me.

The World’s Hope

The Fathers found a great Old Testament prophecy of the Eucharistic mystery in the bestowal of manna in the wilderness. They were drawn to God’s promise given through Moses in Exodus 16:12, ‘In the morning you will eat your fill of bread.’ Origen read the verse in the light of the image of Christ the Morning Star, expounded wonderfully in his sermons on Exodus. The 1947 edition of that text in the Sources Chrétiennes was done by P Henri de Lubac. He appended to Origen’s commentary a marvellous footnote of timeless relevance:

‘To Origen Christ restores to an ageing world perpetual youth. Thus is conveyed the considered sentiment of gladness that bore up the first Christian communities, conscious, at once, of being heirs to a most ancient tradition and yet of embodying a new world. It still depends on the Christian of today whether Christianity will appear to all as the world’s youth and its hope.’

Catholic Politics

Anne Applebaum’s 2020 volume Twilight of Democracy appears with two different subtitles. The first, apparently peculiar to the US is, ‘The Seductive Lure of Authoritarianism’; the second, British, reads, ‘The Failure of Politics and the Parting of Friends’. The autobiographical account of shattered friendships, judiciously interspersed into an otherwise analytical text, invests the argument with human credibility. Applebaum writes: ‘Authoritarianism appeals, simply, to people who cannot tolerate complexity; there is nothing intrinsically ‘left-wing’ or ‘right-wing’ about this instinct at all. […] It is a frame of mind, not a set of ideas.’ This is a helpful and, to my mind, persuasive point of view. It makes me think how urgent it is to revive a truly Catholic politics. As I have argued in a different context, ‘Part of what makes the Church catholic is its capacity to sustain tension, to wait for apparent antitheses to be resolved — by grace, in charity, not by compromise — in synthesis.’ This trait, presupposing clear orientation, is likewise a frame of mind. It is much needed in public life today, even requiring revival within the Church. This is not a time to be wasted on useless, simplifying squabbles. There is urgent, necessarily complex work to be done for the common good.

Not in Numbers

We worry, and hear others worry, about the falling number of people going to church, requesting the sacraments, pursuing a vocation, and so forth. It is right that we should be concerned. At the same time, we require more than a merely human perspective. What is at stake, after all, is a supernatural matter. Do we believe that God is God, or not? Do we acknowledge, and own a need for, strength beyond our own? The story of Gideon’s battle against Midian (Judges 7) is instructive. Called to be an instrument of Israel’s freeing, Gideon turned up before the Lord with 32,000 men. The Lord said, ‘The people with you are too many for me to give the Midianites into their hand, lest Israel vaunt themselves against me, saying, My own hand has delivered me.’ By various procedures, the Israelite army was reduced to just 300. It seemed an absurdly inadequate number; yet the Midianites were routed. Israel was awakened to a truth it had forgotten: God is a living God, a God who saves. This week’s collect contains the confession, ‘we are weak and can do nothing without you’. That is surely part of what, in present circumstances, we are called to take on board, recognising ourselves as we are, God as he is. When this happens, new life is released.

Blame

To say, ‘I did it, it’s my fault’, requires a great deal of maturity. It presupposes readiness to take responsibility, and that is hard at a time when so many influences push us in the opposite direction, nurturing a litigious mentality that always looks to charge what goes wrong to someone else’s account. Brené Brown expounds the dynamics of blaming in this smart little video, lasting no more than three minutes. It is a help to self-examination. Brown remarks that blame is simply a discharging of discomfort and pain. It has an inverse relationship with accountability. Accountability is by definition a vulnerable process. Blaming meanwhile is lodged in anger. It shuts us off from others instead of opening us to them. And so it is one of the chief reasons why ‘we miss our opportunities for empathy’.

European Ukraine?

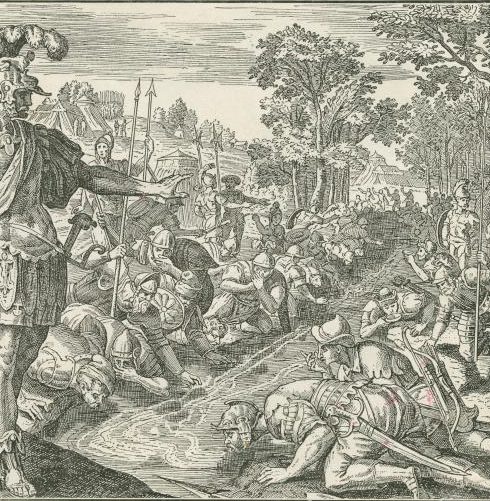

Does Ukraine naturally belong as part of Europe — or not? The Russian aggressor tries to persuade the world that the answer is no. This rhetoric is met with counter-rhetoric, as it must be. Scholars at Harvard’s Ukrainian Research Institute, meanwhile, propose a response based on careful historical research, amassing evidence with which it is impossible to quarrel. They state their purpose modestly as being the creation of ‘a picture of the medieval European world that fits the evidence from the primary sources’. They carry it out by mapping the dynastic connections made between the ruling family of Kyivan Rus’ and the rest of medieval European royalty in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The map needs no commentary. You can access it here. This project makes a particular impression on me as a Norwegian, gratefully remembering that our national patron, St Olav, arrived in 1030 at the battle of Stiklestad, traditionally marking the Christianisation of our country, straight from Kyiv, where he had enjoyed the protection and hospitality of his friend, Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and his Swedish queen Ingegjerd.

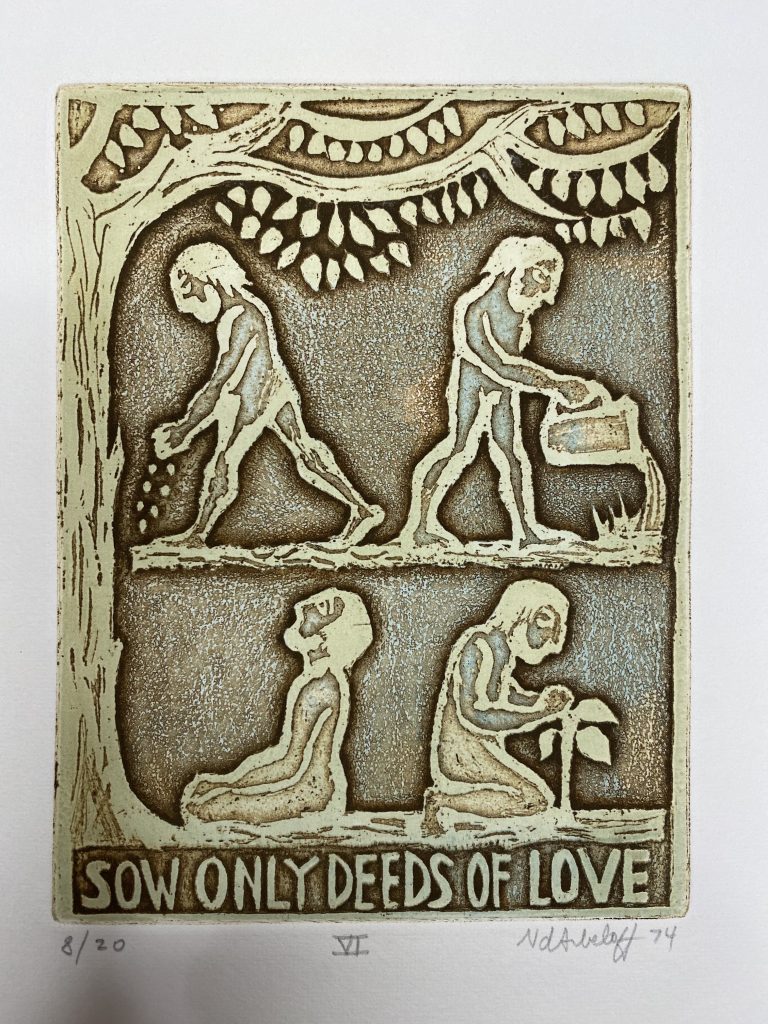

As If By Enchantment

Do not blame your brother for an unloving action. Try to cancel it by performing a loving action in its place. Do not preach moral principles: sow only deeds of love. From there, all the rest will follow as if by enchantment.

Seek no more when love is accomplished, for there is no more to seek. Go to another place where love is still imprisoned and deliver it to the holder of the key.

From The Word Accomplished by A.B. Christopher [Alexander d’Arbeloff]

Serene Statio

It is moving to observe the seemingly endless row of crosses in the cemetery of St Vincent’s Archabbey, Latrobe. More than 700 monks rest here. Some will have lived linear, crystalline, clearly focused lives; others’ lives will have been more contorted. But here, in death, they repose fraternally in peaceful order, lined up in serene statio, waiting for the heavenly liturgy. Whether their fidelity was spontaneous or hard-won, they kept it to the end. ‘Blessed are the dead which die in the Lord‘.

St Vincent’s was founded, as the first Benedictine monastery in the United States, in 1846 by Abbot Boniface Wimmer. He was a man of courage, vision, and more than a little tenacity. Tellingly, his motto was, ‘Forward, always forward’. This missionary monk impressed Pope Pius IX at an audience in 1865. The pontiff is said to have sent him off with the singular valediction: ‘Long live Abbot Wimmer and his magnificent beard.’

Where Have I Been?

Whitsun makes me think of a scene from the last act of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt in which Solveig, on the Eve of Pentecost, sits in her hut and sings. Her life has been one of waiting for the man she loves, who left her, promising to return. Years have passed, yet her confidence in him has not wavered. She sings: ‘If you have much to carry, give yourself time. I shall wait: I promised you that.’ As for Peer, he roams, having all but forgotten her. He is forced, however, to reflect on what has become of his life when a messenger of God confronts him, saying: ‘There’s nothing left of you, only unfulfilled promise.’ He challenges Peer to summon positive proof of personal integrity; else, he warns, he will be melted down and repurposed. He does not even have the mettle for damnation — there’s simply nothing there. That’s when Peer stumbles on Solveig’s hut. Meeting her again, he asks her, genuinely moved, and appalled by the threat of annihilation: ‘Can you tell me where I have been since last we met, where I have been myself, whole and true?’ She answers: ‘That riddle is easily answered. You have been in my faith, my hope, and my love.’ To bear one another’s burdens is not just about helping others; it is about holding their truth before God in love, even when they are lost to themselves. Such is life in the Spirit.

Living Truly

While his nation bleeds, and his pastoral heart bleeds for the nation, Major Archbishop Sviatoslav Shevchuk of Kyiv reflects on essentials. He asks what love stands for. ‘Today the word “love” is so devalued […] that we sometimes do not understand what it means to love. Therefore, the virtue of love should be distinguished from the feeling of liking some wish of ours, a desire, something that we like, something that is dear to us, something that is the subject of our longing. Love, divine love, is complete self-sacrifice, complete self-giving for the sake of the one I love. This is the divine love with which God loves us all, and the fullest manifestation of the content of this divine love that leads to sacrifice are the words, once again of the Saviour Himself: “ For God so loved the world, that He gave His only begotten Son, that whosoever believes in Him should not perish, but have everlasting life” (Jn 3:16). Therefore, the revelation, the full revelation of our God in Whom we believe, is the God of sacrificial love we have on the Cross. When our Saviour dies, He gives His spirit into the hands of the Father and says, “It is finished!” […] It seems to us that when we sacrifice ourselves for another, we die. But the truth is that love is a life-giving force, a force that gives life. When we give ourselves, then we truly live, we live eternal life.’

At Peace with All

Nikolai Gogol’s Meditations on the Divine Liturgy begin with an account of how the priest must prepare himself to celebrate. He should ‘begin from the evening before to be abstinent in body and spirit, should be at peace with all, and should avoid harbouring displeasure towards anyone. From the evening on, after reading the prescribed prayers, he should dwell with his mind in the altar, […] so that even his very thoughts may be duly consecrated and filled with sweet fragrance. When the time comes, he goes to the church with the deacon; together they bow down before the Holy Doors and then kiss the icons of the Saviour and the Mother of God, after which they bow to all present, by this bow asking forgiveness of everyone.’

One doesn’t just stumble into prayer. Body, heart, and mind must be made ready. That takes time. And requires of one commissioned to celebrate the sacred mysteries utter dispossession. It is good to be reminded.

In the Same Boat

When you’re in Minnesota, Norway doesn’t seem too far away, somehow. The landscape is sometimes similar, but that is not all. Tens of thousands of Norwegians came to Minnesota between 1851 and 1920, making the Twin Cities the unofficial capital of Norwegian America. Many here speak fondly of a Great Grandpa Åsmund or a Great Aunt Bergljot. A local luminary like Garrison Keillor can make a statement like, ‘To Norwegians, the polka is a form of martial art’, and expect to draw a self-ironical grin from hearers. My favourite example of the Minnesotan-Norwegian connection is this commercial for Lutheran Airlines. It catches fundamental aspects of a mindset that is instantly recognisable.

‘You’re all in the same boat on Lutheran Air’.

Gratuity

At St John’s Abbey, Collegeville, I am privileged to live just opposite a room that houses a facsimile copy of the St John’s Bible. What an extraordinary creation! The brainchild of Welsh calligrapher Donald Jackson, it is a unique phenomenon in modern publishing: a hand-written, illuminated copy of the entire Old and New Testaments. I am struck by something Jackson says about the project: ‘The continuous process of remaining open and accepting of what may reveal itself through hand and heart on a crafted page is the closest I have ever come to God.’ At a time when most of us are so chained to keyboards that our hands start trembling as soon as we have to write more than just our signature with a pen, it is good to be reminded of the role handwriting can play in enabling understanding, even enlightenment. I am struck, too, by the sheer gratuity of this project, alive with delight. Delight is something most of us could do with more of in engaging with things that lend significance to our lives.

By Being Happy

An interview with the Lithuanian poet Indrė Valantinaitė in this week’s Dag og Tid contains a marvellous exchange. Valantinaitė reflects on the fate of her grandmother, who died in traumatic circumstances.

— We all carry sadness as part of our family histories. The hope is that we can make peace with what is tragic. Then we help those others, too.

—Those who suffered the sadness? How?

—By being happy. By living life to the full. By the experience of freedom. By making peace with terrible happenings. You see what I mean. No, she isn’t here; but thanks to her, I am here. If I am happy, I believe she is helped.

‘I am a religious person’, says Valantinaitė, ‘a Catholic’. She adds: ‘A good poem doesn’t lie. I find strength in poetry. And in faith. Poetry and prayer heal.’

Hyperbole

I am on a journey. Before departure, an email from the airline warbled, ‘We look forward enormously to welcoming you onboard’. Enormously? The affirmation contrasted with the flight attendants’ weary gestures. The receipt from the airport hotel told me, ‘We hope you had an amazing stay’. Even a bottle of fruit juice in the departure lounge is rich in aspiration: ‘You are special! Treat yourself kindly!’ I find all this wearying.

Why do we revel in automatically generated assurances that we, like every one else who spends money in the furtherance of a particular enterprise, are uniquely wonderful? Why do we put up with this overwrought rhetoric? It is time to reaffirm the nobility of the ordinary. That, after all, is what life mostly consists of. It would be a shame to miss out on it.

A Future

Over the past few days, given the encirclement of Ukrainian forces in the region of Donetsk, there has been speculation in the media about whether negotiation with the aggressor will — should — ensue. It is useful to re-read Professor Timothy Snyder’s recent talk to the Kyiv Security Forum. It bore the title, Why Ukrainian victory is important for the world. Especially thought-provoking is Snyder’s tenth and final reason. It touches a tendency of retrospective myth-making whose influence is felt in other areas, too; indeed it shows signs of becoming culturally axiomatic. ‘Russian propaganda is all about the past, it’s all about how things are predetermined, it’s all about seeking some kind of moment at some point in history where we were right and everyone else was wrong. But that is not what we need. We need, everyone needs, a future. We need a politics of the future; we need an event that can break us out of our rut and which will point us towards a future.’ To opt, then, for prospect. This will mean assuming responsibility for life, nurturing a will to live, for others to have life.

Lifted Up

a child walks alone through the forest of grief

without being afraid

it is only the forest of grief, says the child,

I shall walk here awhile while I wait

a child walks alone through the forest of grief

it waits not, just walks slowly on

seeing all there is, touching it

I am because I am, says the child

a child walks alone through the forest of grief

only by walking alone can I find my way

I shall lose all I find

and all that I lose shall be mine forever

a child walks alone through the forest of grief

I hear best when all is quiet, says the child,

then I hear that I am not on my own

I walk alone and am lifted up to where I cannot reach

Tora Seljebø

Tragedy

The word ‘tragedy’ is much overused nowadays. This is a paradox, given that we’ve largely forgotten what it means. When we say ‘tragedy’ we tend to have in mind ‘a very sad occurrence’. To the ancients meanwhile it meant something more like ‘a great commotion or disturbance’, notably in the form of a public spectacle. If such disturbance or commotion awakens us inwardly, it can be beneficial without necessarily being pleasant. The force of tragedy was brought home to me afresh last week when, on account of a spot of Covid, I had leisure at last to read Oliver Taplin’s 2018 version of Aeschylus’s Oristeia. Compellingly readable, it is characterised at once by nobility and verve. One is spontaneously drawn to read it aloud. It is hard not to feel a twitch of nostalgia for days in which exposure to texts of such profundity was a prerequisite for public discourse, thereby held up to an exacting standard. We are reminded of the peril inherent in seeing things as they are in Cassandra’s outburst: ‘Again the piercing anguish/of foretelling true comes swirling up/and thrums me with discordant preludes.’