Recalibration

‘Man’s ability to see is in decline. Those who nowadays concern themselves with culture and education will experience this fact again and again. We do not mean here, of course, the physiological sensitivity of the human eye. We mean the spiritual capacity to perceive the visible reality as it truly is.’ Thus wrote Josef Pieper in the 1950s, in a passage cited this morning by Elizabeth R. Powell at a symposium held in Trondheim under the title, Seeing Nature. We’ve become a lot worse since Pieper.

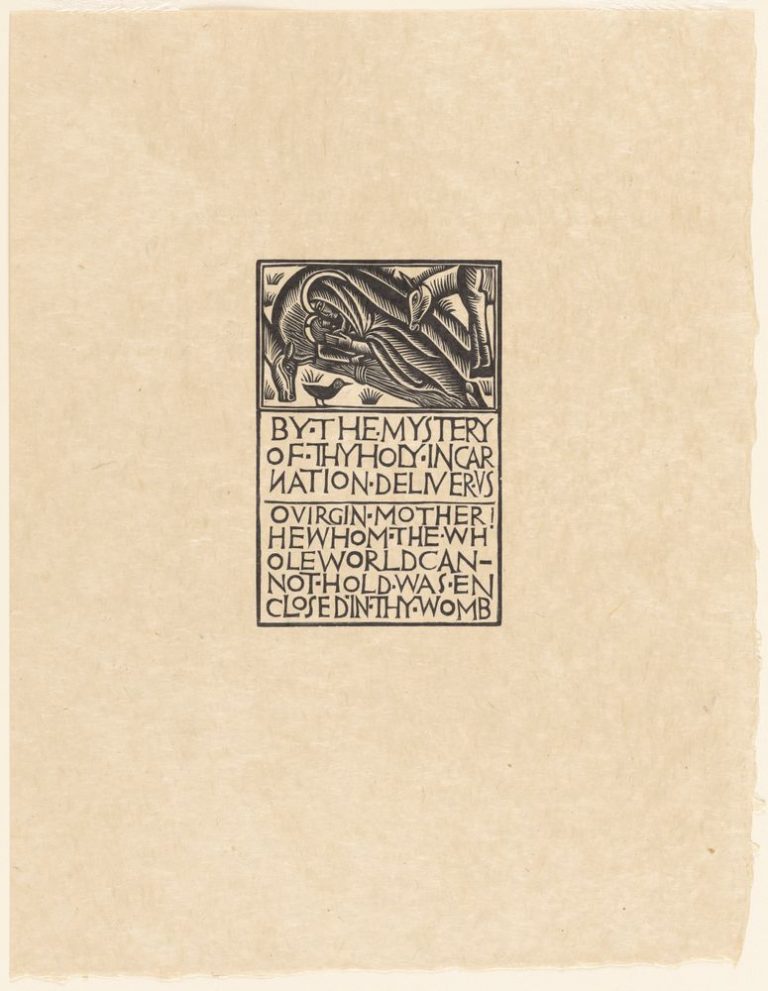

Powell went on to perform an exercise in seeing by means of close analysis of David Jones‘s engraving from 1924, The Nativity. Notice the middle ‘n’ in the word ‘incarnation’. The inversion, we were told, was probably a simple mistake (an engraver must carve his work as a mirror image), yet one rich in significance, for God’s becoming man is the source of ‘multiple inversions’. To relearn to see, we must ‘recalibrate our senses to the wonders of the small’. Then great discoveries, perhaps even revelations, await us.

Ars moriendi

‘Modern societies’, writes Emily Wilson, ‘are peculiar in the degree to which we segregate the dead from the living.’ Monks are in this respect blessedly countercultural. They live and die within an ancient wholeness. A monastic death is a community affair. The community watch with the dying brother, offering prayers and the comfort of friendship. When death occurs, the body is washed, then brought to the church with singing; there it remains, in the middle of choir, illumined by the paschal candle, always with a praying monk at its side, until it is carried out, again with song, to be buried in a grave dug by the brethren’s hands. A Cistercian is buried without a coffin, on a plank. It’s a way of honouring in death the simplicity that marks our life. It’s also a way of making explicit the symbolism of John 12:24: ‘Unless the grain of wheat…’ This tactile, familiar engagement with death is in no way morbid; on the contrary, it is reassuring and freeing, as those who attend a monastic funeral can testify and as many viewers of the film Outside the City have remarked. It is a way of healing the estrangement of what Wilson calls ‘our peculiar modern desire to mourn the dead without having to touch them.’

A Heart Changed

How often are we not told, ‘Do as your heart dictates!’ In a symposium in Hildesheim today on what the Benedictine patrimony can contribute to the Church’s mission, Mother Christiana Reemts, abbess of Mariendonk, picked up this imperative and said, ‘I hold it to be quite false’. She explained what she meant by pointing out what we know from experience and what Jeremiah pointed out almost cruelly: ‘The human heart is deceitful above all things’ (17:9). Our heart is not an infallible compass; it is subject to many temptations, tensions, and trends. Before it can guide us reliably, it must be oriented and, when necessary, healed. The great Christian task which the monks or nun exemplifies, said the abbess, is ‘to let the heart be transformed by God’s Word — then to listen to this transformed heart’. How liberating to hear a voice speak such basic truths, truths that, once one has assimilated them, seem self-evident. There is more food for thought, in German, on the abbess’s blog.

German Renewal

When Gotthard, abbot of Niederaltaich heard of his appointment as bishop of Hildesheim in 1022, he is said to have said, ‘Lieber in Bayern ein Abt als droben ein Bischof’ (‘Rather abbot in Bavaria than bishop up there’). Yet up he went, beginning a ministry that was singularly fruitful. Gotthard was canonised in 1131, the foundation year of Tintern Abbey. Today, on his liturgical feast, the diocese of Hildesheim inaugurated a Godehardjahr, not only a year of commemoration, but of prospective mission. At the opening Mass, Gotthard’s successor, Mgr Heiner Wilmer, summoned the entire diocese to ‘Benedictine renewal’. In a rousing sermon he said: ‘For us in the diocese of Hildesheim, this is about inner change and transformation in Christ.’ Much is being written and said at the moment, not least in Germany, about the problems of the German Church. How marvellous, then, to witness such a life-giving initiative, bearing the hallmarks of unity, hope, and Benedictine humilitas, focused on and oriented towards Christ to whom, St Benedict insists, ‘nothing is to be preferred’.

Odysseus

One of the endlessly fascinating things about the early Church is the way in which the Fathers (and Mothers, too, though they left less evidence in writing) used classical culture as a way of illuminating Christian revelation. Many of them knew Homer by heart. The story of Odysseus’s return from Troy shaped their consciousness. The passage in which he had himself tied to the mast to resist the sirens’ call had special appeal. In it they saw an image of the Christian’s return to the Homeland in a voyage marked by ‘glorious risk’, καλὸς κίνδυνος. The sirens symbolised ‘the world’ as the New Testament writers understood the term: creation as opposed to God, endeavouring to draw us away from him. St Jerome wrote in his commentary on Isaiah (PL 24, 216B): ‘The sirens still repose in shrines of pleasure. By means of a sweet but death-inducing song, they pull souls into the depths.’ I dare say that peril is still to be reckoned with, but are we able, in this day and age, to recognise the sirens’ warbling for what it is?

Shepherding

In the rite of consecration of a bishop, the consecrator gives the newly ordained his staff and says: ‘Receive this staff, a sign of your calling to be a pastor. Watch over the flock which the Holy Spirit has appointed you to govern in the Church of God.’ My own staff, a gift from a faithful friend, was made in the workshop of the Hungarian master silversmith Kristóf Gelley. He has just released a video recording the process of creation. You can find it here — a testimony to craftsmanship of the highest order.

A pastoral staff is crooked as a means of catching hold of the hind legs of sheep in flight from the fold: that, too, is part of the shepherd’s task! The crook on mine, which recurs in my seal, is modelled on the seal of St Bernard of Clairvaux. The cross is Byzantine (you may refer to this exquisite example), a reminder of all I owe the rich tradition of the Eastern Church, which is nourishingly present, too, in the heritage of Nidaros.

Purity of Heart

Great purity can exist in the midst of ugliness. Darkness can help us perceive the brilliance of light, be it small and placed at a distance. It impresses me that the Major Archbishop of Kyiv, Mgr Sviatoslav Shevchuk, should choose to reflect on purity of heart today, even as we may be tempted to avert our gaze from atrocities committed in Ukraine. His words, which I’ve compressed very slightly, are an inspiration:

‘To be pure in heart means to see God present in my heart; to build a pure relationship with him, not a selfish one, not using God as a means to achieve my own goals or satisfy my own lusts and passions. To see God in your heart means to share in his resurrection. The Lord God gives man this gift of resurrection in the sacrament of baptism. The fullness of God’s presence must be manifest in our relationship with God and neighbour. May the Lord God show his face in Ukraine. May he bless Ukraine through pure-hearted people who, even in the circumstances of a brutal war, know how to maintain their purity. People who look into the face of God, then see his image in every person, then try to serve God present in a specific other. Such people are already blessed. Such people rejoice in the purity of their hearts, and they see God.’

Musical Preaching

At a time when the cult of Stalin is enjoying a perverse revival in the east and we may even be witnessing a stab at reincarnation, it is good to recall those who resisted the dictator with resolve, at great cost. One such was Maria Yudina, among the greatest pianists ever to have lived. Gloriously eccentric, she slept in a bathtub and routinely gave away her concert fees to members of her audience. She was unflinching in her Christian confession. Do watch this noble documentary. When Stalin, who admired her, sent Yudina a gift of money, she replied, ‘I will pray for you day and night and ask the Lord to forgive your great sins before the people and the country.’ As for the money, she added, she had given it away. She was serially ousted from public life and lived in penury. Shostakovich knew and revered her. After her death caused by an error in medication, he said, ‘She always played as though she was giving a sermon’. You will get a sense of what he meant if you listen to this recording of Beethoven’s 4th Concerto.

Ah, if only more preachers preached as if they were playing Beethoven!

Yom HaShoah

How I miss the voice of Jonathan Sacks (1948-2020)! Fortunately it still speaks to us in his writing, as in an address for Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2020 — a remembrance crucial to us all, kept by Jewish communities on this day.

‘The Holocaust has become more than a Jewish tragedy. It has become, for the West, a defining symbol of man’s inhumanity to man. […] We remember whole communities of Jews from Sweden in the north to Greece in the south, from France in the west to Russia in the east – people who were no conceivable threat to anyone – who vanished into the black hole in the heart of Europe. Among them were families who had lived in certain lands for almost a thousand years and yet they found they were still regarded as strangers without the most basic of human rights, the right to life. […] Those who hate need no reason to hate. Jews were attacked because they were rich and because they were poor. They were condemned as capitalists and as communists. Voltaire accused them of being primitive and superstitious; others called them rootless cosmopolitans. Antisemitism was protean and logic-defying. It exists in countries where there are no Jews. That is why Holocaust remembrance must not be confined to Jews alone. The victim cannot cure the crime. That demands the rule of law, a respect for justice, and a constant effort of education.’

Judgement

This fragment of ‘The Last Judgement’ by a follower of Hieronymus Bosch was painted some 200 years after Dante wrote his Divine Comedy. It is striking that both artists, evoking the reality of hell, as a matter of course put several mitred prelates in it – indeed, there is even a cardinal’s hat in evidence here in this picture. I don’t think such representation necessarily suggests that high clerics were or are more hellishly inclined than others (although in some cases this may be the case); it is rather an uncompromising reminder of the principle, ‘Every one to whom much is given, of him will much be required’ (Luke 12:48). If one happens to be a bishop photographing this painting, able subsequently to espy, albeit faintly, one’s own reflection in the glass, there among the reprobates, one prays spontaneously for mercy and the gift of fidelity, recalling with gratitude another line of Scripture: ‘The one who calls you is faithful, and he will do it’ (1 Thessalonians 5:24).

As a Child

At first sight, this angel seated in the cemetery outside the Münster of Frauenwörth seems a charming, innocent example of Bavarian Baroque. Only on closer inspection does one notice that he rests his left elbow cavalierly on a skull. Is this a sinister manifestation of the principle, ‘Et in Arcadia ego’? An example of Christians’ obsession with mortality? A superficial observer might think so. I don’t. No, the monument makes me mindful of this lovely reflection by Dom Porion (in Écoles de silence):

‘If instead of being frightened of God we really trusted him, we should fear neither the world nor the flesh nor pain, neither the past nor the future, neither others nor ourselves. We should consider this world as a child considers a ball in his toybox, and a ball of bad quality at that, a ha’penny ball; and we should play with death as with an elderly nursemaid. As long as we trust in God we are agile and strong. The day we lose our trust in God we languish, even if no real danger is in sight.’

Hope

Easter stands for the rebirth of hope. When, as Christians, we say to someone who has lived through terrible things, ‘Don’t lose hope!’, the statement is no vague moral boost, but a pointer to something, someone substantial. To hope for myself is also to have hope for others. Benedict XVI stated this magisterially at the end (§48) of Spe salvi, affirming that ‘no man is an island, entire of itself. Our lives are involved with one another, through innumerable interactions they are linked together. No one lives alone. No one sins alone. No one is saved alone. The lives of others continually spill over into mine: in what I think, say, do and achieve. And conversely, my life spills over into that of others: for better and for worse. So my prayer for another is not something extraneous to that person, something external, not even after death. […] Our hope is always essentially also hope for others; only thus is it truly hope for me too. As Christians we should never limit ourselves to asking: how can I save myself? We should also ask: what can I do in order that others may be saved and that for them too the star of hope may rise?’ This is profound and beautiful theology. It is also (should also be) the foundation of Christian politics.

Mysterium Magnum

When I recently discovered Hugo Rahner’s great work about the Symbols of the Church (with which I once spent much time) in a secondhand bookshop, I rejoiced as if I’d met an old friend. I spontaneously felt like taking the book out to lunch.

Published in 1964, full of hope for the realisation in the present of ancient plenitude, it is a book to re-read now. Its very first sentence is apposite:

‘Since Paul in Ephesians 5:32 wrote the inspired word about the mysterium magnum which obtains between Christ and the Church, we can ever again, in the course of the history of dogma, deduce the Christian integrity and intellectual profundity of a theological system from the way in which, within the construction of the whole, the chapter on the Church is integrated.’

Rising

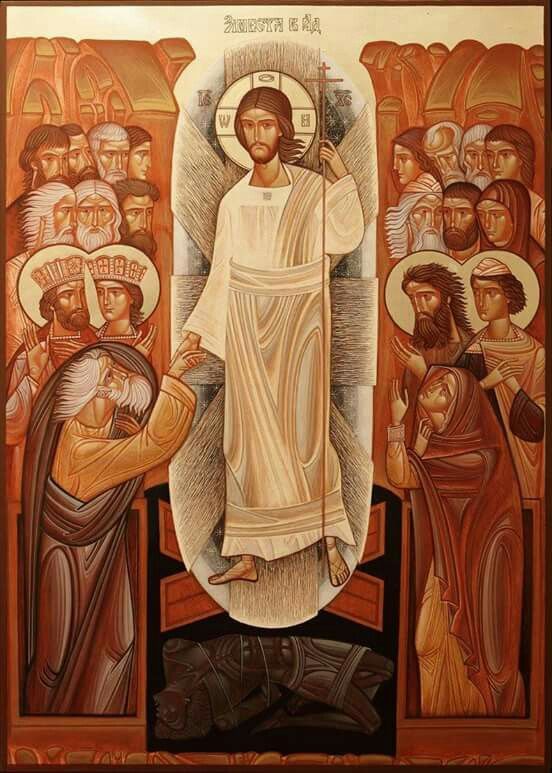

This icon by the Ukrainian iconographer Lyuba Yatskiv renders with grace the message of a Kanon for Easter Sunday composed by Cosmas of Maiouma (floruit ca. 730).

‘You came down to the depths of the earth to accomplish all your glory; my presence in Adam was not hidden from you; through your burial, compassionate Lord, you have brought new life to me when I was dead. You have opened your arms and joined together what before was parted. You released those who were held fettered in linen shrouds and under gravestones, and they cried out: There is no one holy but you, O Lord!’

Gaudia paschalia! May Christ’s holy Resurrection bring healing and peace to our weeping world!

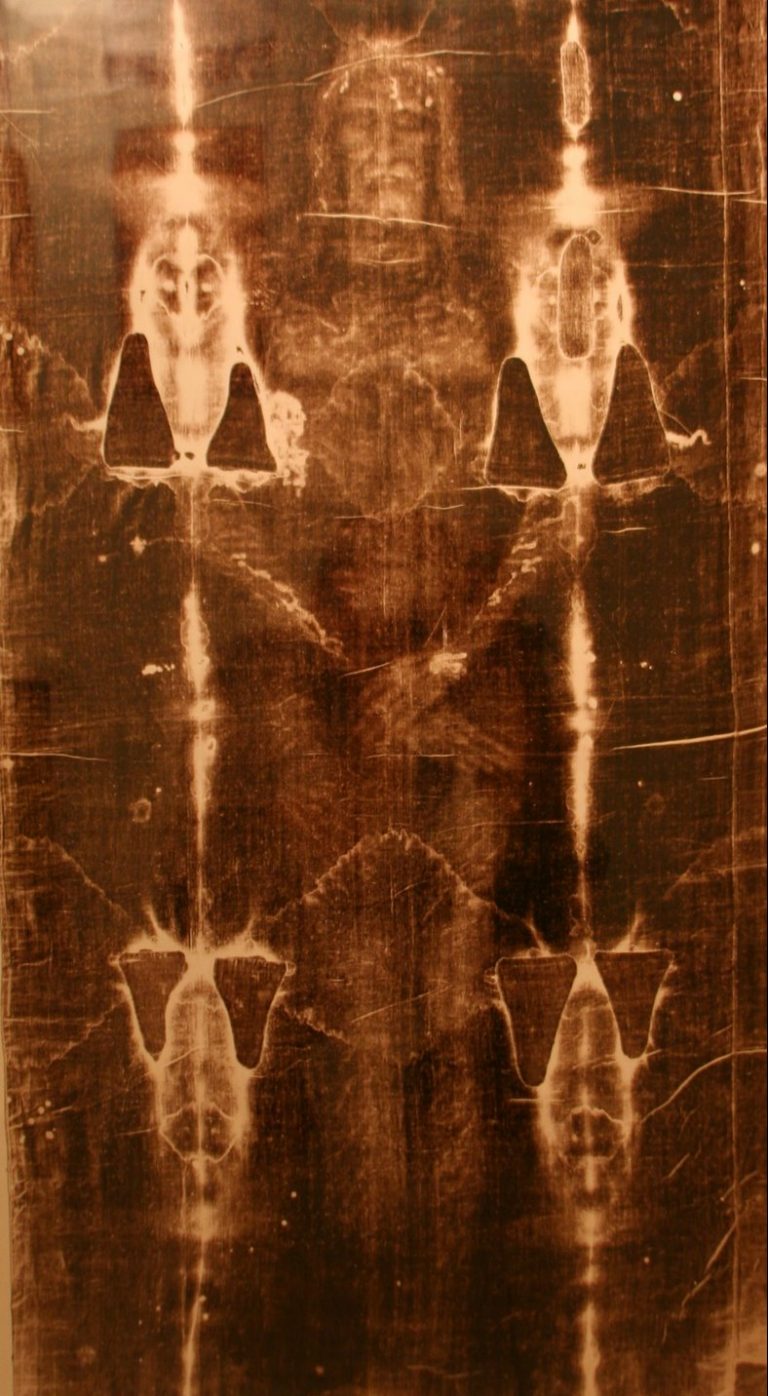

Rest

The passage from the Letter to the Hebrews which the Church gives us today in the Office of Readings speaks of God’s rest, which evokes the whole atmosphere of Holy Saturday. The profundity of the rest may be gauged from the fierceness of the battle that preceded it. In this interview, Patrick Pullicino – a priest and professor of neurology – proposes a physiological reflection on Christ’s Passion inspired by a careful examination of the Shroud of Turin. There is rich material, here, for mediation in awe and silence. There is also a prompt to make our own the tender, grateful prayer of the final chorus of Bach’s St John Passion, Ruht wohl, ihr heiligen Gebeine, ‘Rest in peace, you sacred limbs; and bring me also to rest.’

Cross

The image of the crucifixion is now so embedded in Christian consciousness — and in outsiders’ perception of Christianity — that we easily forget how long it took to emerge. This panel from the main door of Santa Sabina on the Aventine in Rome is the earliest known representation of Christ crucified made for a devotional purpose. It was produced in the first half of the fifth century. Cicero, voicing a classical Roman’s point of view, had written that ‘the very word cross should be far removed not only from the person of a Roman citizen, but from his thoughts, his eyes and his ears. For it is not only the actual occurrence of these things, but the very mention of them, that is unworthy of a Roman citizen and a free man’ (Rab.Perd. 16). This gives us an idea of the revolution in sensibility that issues from Good Friday. It gradually enabled Christians to perceive the cross as a manifestation of grace and to sing as in a Lauds antiphon this morning: Propter lignum venit gaudium in universo mundo — ‘throughout the world, joy has come through the wood [of the cross]’.

Feet

The Sacred Triduum displays the unfathomable mystery of God’s personal, unique love for each of us. To believe in the possibility of such love, we need to practise it and discern the face, the name, the soul of men and women who can easily seem featureless, obliterated by a fog of prejudice. Someone who practises this art of humanity, and bears witness to it, is Katja Oskamp, whose Marzahn, mon amour: Confessions of a Chiropodist (now available in English translation) is a wonderful book. Oskamp speaks of the vulnerability and shame people feel on revealing their feet to another: ‘Whether they’re labourers from a building site or vain fellows covered in tattoos, whether they’re pregnant or old ladies, spiritual low-flyers or academics, all apologise, the first time they remove socks and shoes, for their feet.’ Her observation sheds light on the significance of the foot washing in the Upper Room, which we enact liturgically, as if for the first time, each Maundy Thursday.

Membra Iesu nostri

As every year, I find myself on Palm Sunday struggling to look ahead. Rationally I know that within a week we shall have celebrated Easter, yet the prospect seems almost unreal given that, between now and then, we shall by means of the Paschal mystery have re-lived liturgically — that is, with high realism — the entire history of the world, seeing it through to fulfilment in the eschaton. In the Ambrosian rite, Holy Week is known as the Hebdomada authentica, the week that sets the measure of all other times. It is a helpful notion. It puts experience in perspective. Where words fail, music can help. I love Buxtehude’s Membra Iesu nostri, the setting of a text attributed (wrongly, probably) to St Bernard of Clairvaux. Through what is largely a mosaic of Scriptural passages, the cantata takes us to the heart of Christ’s sacrifice and the grace it confers. The video quality of this recording with René Jacobs shows its age, but the ensemble’s interpretation is possibly unsurpassed. The text can be found here.

The Cardinal

Otto Preminger’s 1963 picture, loosely based on the life of Cardinal Spellman, was a box office hit, though critics were snooty about it. Bosley Crowther, reviewing it for the New York Times, remarked of the protagonist: ‘The young priest, played by Tom Tryon, is no more than a callow cliché, a stick around which several fictions of a melodramatic nature are draped.’ To watch it again sixty years down the line is to be clementer. It is now so rare in cinema to find representations of Catholic clergy that even approach three-dimensional credibility that one spontaneously awards high marks for effort. The film represents an image of priesthood after which young people today supposedly hanker, though I suspect the situation is in fact more complex. What strikes one most is the fact that the Church (notwithstanding obvious failures of individuals throughout the film) could be portrayed in a mainstream medium back in ’63 as representing, at some deep level, moral authority, be it one against which people railed. This marks such a contrast with the present day that it really makes one sit up — to realise what a task we’ve on our hands.

Remembering Names

The initial wistfulness of Lea Ypi’s memoir of growing up in communist, then post-communist, Albania reveals itself a rhetorical device in the unfolding of a political parable. Ypi exegetes the perfidy of concepts. In her childhood, everything and everyone was labelled. By the criterion of loyalty to Uncle Enver, all things fell into place. Even hairstyles could be described as loyalist or imperialist. The revolution of 1990 caused order to unravel. Ypi, still a child, discovered that many people, including her family, ‘had simply mastered the slogans’ without believing in them. It caused her a trauma. ‘I believed. I knew nothing else. Now I had nothing left.’ The book is an account of her piecing together a sustainable account of society. It is seasoned with humour; but the tragic is never far away. No reader will quickly forget Ypi’s friend who, at fifteen, was trafficked overseas to work the streets of Milan. Or the image of her father, charged with the management of a seaport, manically rehearsing the names of hundreds of Roma workers whom he refused to lay off: ‘If I forget their names, I will forget about their lives.’ The Albanian revolution, writes Ypi, had been ‘a revolution of people against concepts.’ How hard this outlook is to maintain over time.

Existential War?

In today’s audience, the Holy Father firmly condemned the massacre of Bucha, calling again for peace. In the light of what has taken place in Ukraine in the past 48 hours, Sergey Karaganov’s recent conversation with Bruno Maçães, is even more preoccupying. Karaganov, a former adviser to Putin, affirms: ‘Russia cannot afford to ‘lose’, so we need a kind of a victory. And if there is a sense that we are losing the war, then I think there is a definite possibility of escalation. This war is a kind of proxy war between the West and the rest – Russia being, as it has been in history, the pinnacle of ‘the rest’ – for a future world order. The stakes of the Russian elite are very high – for them it is an existential war.’

I find myself thinking of a speech Otto von Habsburg made almost twenty years ago, in 2003, looking eastward and pointing presciently to Europe’s gullibility in taking its security for granted.

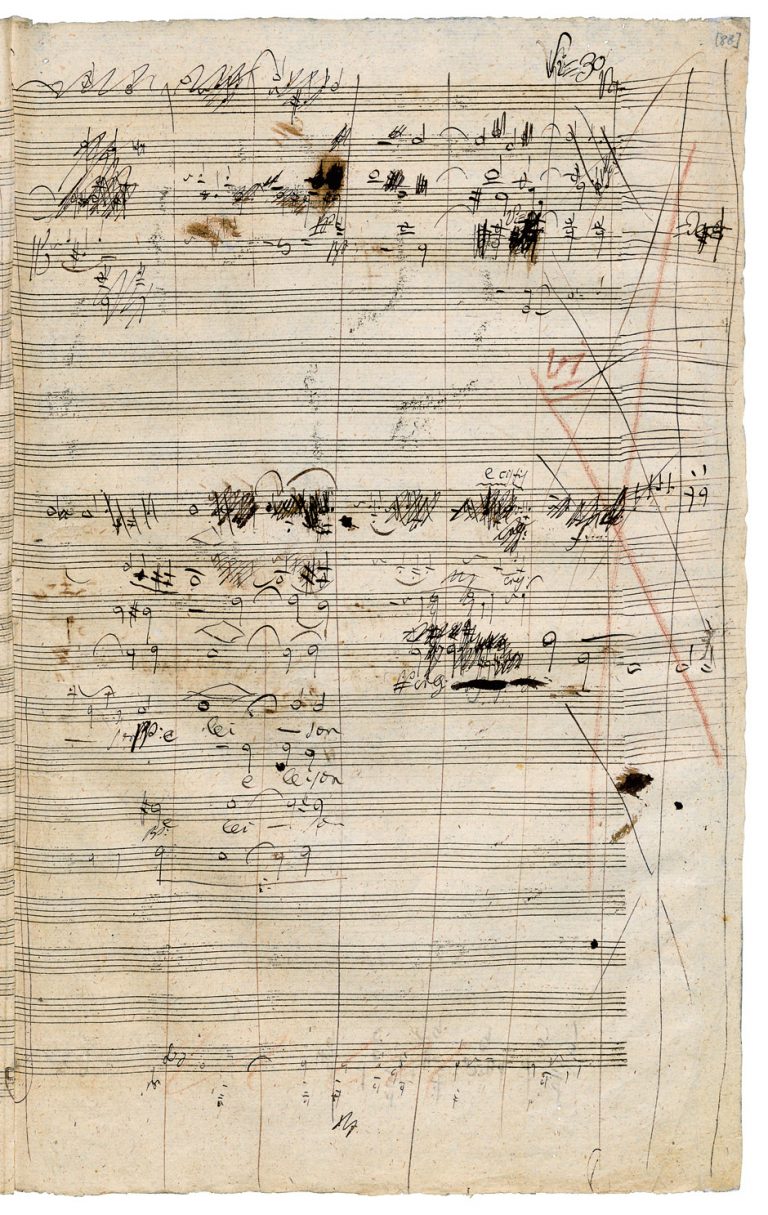

To the Heart

In a beautiful brief essay on Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis, Fr Robert Imbelli cites James MacMillan’s claim that it is ‘one of the most deeply Catholic works ever written’. It is also, he adds, ‘a magnificent affirmation of Catholic humanism, accenting at its midpoint the good news, both scandalous and salvific, that God became man.’ Imbelli says it took him a long time to discover this work from within. I had the same experience. For years it seemed to me too bombastic, too full of contrasts, too little like an act of worship. The interpretation that to me unlocked its mystery was Thielemann’s 2010 performance at the Semperoper in Dresden, commemorating the city’s destruction during World War 2. There is a quality of earnest attention in both performers and audience (which includes Mikhail Gorbachov) that is moving and contagious. The soloists proclaim their parts as if they were evangelists. At the end, everyone stands, in perfect silence. Beethoven inscribed the score with the words: ‘From the heart—may it go to the heart.’ And there, suddenly it entered mine.

Lost in Thought

How one wishes that every architect of public policy would read Zena Hitz’s Lost in Thought, part testimony, part manifesto. It’s not only a highly interesting book; it’s an important one. Hitz puts her finger on a sore point in modern Western society: the fizzling out of the meaningful transmission of culture with a resulting loss of sharable criteria for community-building. Among the causes identified is this: ‘Colleges and universities once held central a practice whose success was evident and that therefore provided an endless source of confidence. That practice is called teaching, and it consists in the person-to-person transmission of the habits of mind that underlie all serious thinking, reflection, and discovery.’ Instead, she contends (rightly, I think), university campuses increasingly turn into playgrounds, the distance between staff and students widens, the quality of education becomes less serious, while disconnected prestige academics churn out reams of research ‘completely disconnected from any recognisable human question’. If you wonder what can be done about it, read the book, which is anything but gloomy. Indeed, it explicitly dissuades from ‘the deliberate choice of a miserable existence’.

Only a Little

We’re acutely conscious right now of the role propaganda plays in war. The deployment of information — or misinformation — can be tantamount to taking up arms. Christian Krönes’s portrait of Brunhilde Pomsel, Ein deutsches Leben, released in 2016, when the protagonist was 105 years old, makes for timely, challenging viewing. For having been Goebbels’s secretary from 1942 until April 1945, Pomsel regarded herself, after a lifetime’s pondering, as having been purely incidental to the drama of war. She owned no responsibility. ‘There is no justice’, she remarked, still indignant at having been interned by the Russians in 1945: ‘After all, I’d done nothing except type for Herr Goebbels. Of what lay behind it all, I knew nothing — or only very little. No, I would not see myself as culpable.’ Her long monologue, shot in black and white, shows (by way of counter-witness) what courage it takes to stand aside from the crowd. Only exceptional individuals are naturally courageous. For most of us, courage requires cultivation. On such cultivation the notion of the ‘free world’ depends. Pomsel said: ‘For my part, I am one of the cowards.’

Ubi caritas

In a Lent homily preached more than 1,400 years ago, Pope St Leo the Great said something stirring. Commenting on St John’s assertion, ‘God is love’, he placed the accent emphatically on ‘is’. He exhorted his hearers: ‘Let the minds of the faithful examine themselves. Let them, by truthful enquiry, evaluate the intimate stirrings of their hearts. Then, should they find in their consciences some repository of love, let them not doubt that God is present in them. Let them be ever more expansive in works of persevering mercy in order to be ever better able to put up such a guest.’

To be on the look-out for this effective presence of a personal, divine love in oneself and in others is to awaken to the sacramental nature of existence. It is also to be gradually relieved of the tendency, common to most of us, to mistake means for ends.