The Place to Be

Professor Kristin Aavitsland has permitted me to share her impressions from a visit to Santa Maria della Pace in Rome last Friday: ‘It was the place to be on the first Friday of Lent, a week after the invasion of Ukraine, even if we’d turned up on a scholarly errand. A fervent, protracted rosary for prayer was going on, suitably enough in just this church. In a strange way it was as if the people praying, women almost all, were united to the saints who are depicted there so wonderfully. They too are predominantly women, women of prophecy and action, who by words, writings, and deeds stood up to tyrants, reproved the mighty, and risked their lives for the sake of justice and peace: Catherine of Siena and her namesake from Alexandria, Birgitta of Sweden. Within the spatial whole of the church they enter into a kind of dialogue with Raphael’s sibyls, likewise prophetic presences. At the heart of it all, of course, is Our Lady of peace. Above the entrance to the choir there’s an inscription: In terra pax. All this, the inscription invoking peace, the frescoes, the intense prayer for Mary’s help, brought the choir together in a single tonality. It was beautiful and soul-stirring. I think the students of the history of art were also touched. God help us for what is going on in Ukraine.’

The Pity of War

Following news from Ukraine, one can feel overwhelmed. It matters to root the tragedy in human particulars, as the BBC’s Jeremy Bowen did this morning, reporting from a railway station in Kyiv (from 11:35). ‘Fathers stood on the platforms waiting to see their families off. […] A man called Alexander sobbed as he waited for the train to leave. He’d put his wife and two small children on board. Alexander wouldn’t let go of a small toy ambulance his eight year-old son had given him as he put them on the train. He kept playing its siren. All the heartbreak of the war was on one man’s face. […] Many of the volunteers are young men, boys barely old enough to shave. […] They were dressed for a camping weekend or a festival, except they were carrying newly issued Kalashnikov assault rifles. One had brand new white trainers. Another had a yoga mat to sleep on. If they were scared, they didn’t show it. Like the other young men with them, they had the courage, patriotism, and sense of invincibility of all the other generations who have signed on to fight for their countries in Europe’s war. Their families will pray they will not have to learn the same brutal lessons. The older men looked much more apprehensive.’

Bishop’s Babble

I’ve been kindly invited by the association of Norway’s Catholic Youth to record brief reflections for Lent under the flattering title ‘Bishop’s Babble’.

There’ll be a weekly contribution (in Norwegian) every Friday until Easter. You can find the series here.

Prayer & Fasting

People often ask: How can I learn to pray? The obvious answer is: pray with the Church through the liturgy and sacraments.

However, a more intimate life of prayer is also called for. We long to pray in a way that expresses our deepest being. We long for the prayer of the heart.

I have found invaluable guidance in a slight volume published in French in 2001. Its title was, ‘The Prayer of the Heart’. Its author was designated as ‘A Carthusian’.

As an offering for Ash Wednesday, I would like to share a translation of this precious resource. You can find it here.

‘Lord, teach us to pray!’ (Luke 11:1).

The Way We Look

Still on the subject of the way we look at things, I’ve revisited Sam Mendes’s film from 1999, American Beauty. I was troubled and fascinated by it at the time, to the extent of presenting a paper on the movie to a theological society. I agree with what I said then about Mendes’s exploration of the boundary between the virtual and the real. The film ‘provides paradigmatic evocations of human beings frustratedly seeking the Other in each other, in the natural universe, and in God, wanting to transcend themselves in love, but repeatedly falling back on a painful, pitiless solitude in which ‘you can rely on no one except yourself’. Faced with such existential anguish, theologians have a duty to engage anew with essentials, telling again the story a God who does ‘look right at us’ and who does invite us to look back, not with a ‘demonic’ gaze set to dominate and possess, but in an ‘angelic’ serenity which freely admits the freedom of the Other, whose Beauty is boundless communion.’

You can find the full text here.

Sight

Some words Jean-Louis Thiériot wrote for Le Figaro this weekend resound in my mind: ‘In Europe, war is back. Our seventy years of peace have been nothing but a happy parenthesis. Only simpletons will be astonished. The warning signs were clear to behold: ex-Yugoslavia, Georgia, Donbas, Nagorno-Karabach. Power and the sword reestablished themselves long ago as the world’s axis. The apostles of the end of history and of happy globalisation were not, however, disabused of their illusions. They had forgotten what Péguy once insightfully said: ‘We must always speak that which we see; above all, we must always, and this is more difficult, see that which we see.’ They had forgotten, too, that history is tragic and that the gordian knot is often cut in blood.’

‘Lord, that I may see!’ is a culminating prayer in the Gospel. Sight is, a lot of the time, neither comforting nor comfortable. But it’s by seeing that we establish ourselves in reality and, so, are able to address it.

Interaction

In the austere definitions of theology, it is sometimes said that the mystery of the Blessed Trinity can be expressed in terms of three subsistent relations. It is not, to put it crudely, about three Persons with relationships; relation is the foundation of Personhood. The idea that originating reality is relational seems dizzying at first. Gradually it liberates thought. It is susceptible of transposition into the realm of human experience and psychology. Quantum physics uses a related paradigm to explain the physical world. It is fascinating to read the following in a book by Carlo Rovelli: ‘[The equations of quantum mechanics] remain mysterious. They do not describe what happens to a physical system, but only how one physical system is perceived by another physical system. What does this mean? Does it mean that the essential reality of a system is indescribable? Does it simply mean that there’s a part of the story still missing? Or does it mean, as I think, that we must accept the idea that interaction is reality?’ In a 2017 interview, Rovelli specified that ‘objects are just the nodes of interactions. They’re not a primary thing; they’re a secondary thing, I think.’ To think like that is to re-think everything.

Autonomy = Freedom?

Romano Guardini was the subject of Pope Francis’s doctoral research. It has often been said that his influence on the pontificate is great. One listens attentively, then, when one of the finest living experts on Guardini, and his biographer, comments on trends in the Church. In a recent conference, Professor Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz offered a global perspective on the Synodal Path, in which she participates with vigour and intelligence. It unfolds, she observed, in a context that absolutises autonomy. Our sense of autonomy is now so strong ‘that whatever God (or the Church) puts before me in terms of commandments, counsels, or wishes is defined as heteronomous. Only when it accords with my own autonomy will I follow it.’ We say no to self-transcendence. We assume that freedom affirms itself against God, perceived as an Adversary — or simply refashioned in our image. Largely lost are light-charged, revealed notions of God and humanity. We’re surrendered to our own obscure longwindedness. Our time’s radical questioning, says Gerl-Falkovitz, is like a thermometer revealing an infection that has long, perhaps since the Enlightenment, been latent. It would seem that what we really need is not self-help, but a Physician.

Pray for Peace

On 29 September 1938, Francis Poulenc found an excerpt from a poem by Charles d’Orléans (1394–1465) reprinted in Le Figaro. The text, profoundly topical, moved him. He set it to exquisite music. This song has been ringing in my ears ever since, this morning, I read of Russia’s invasion of the Ukraine:

Pray for peace, sweet Virgin Mary,

Queen of heaven and mistress of this world.

Kindly cause to pray

the company of saints and direct your plea

towards your Son, beseeching his highness

to have gracious regard for his people,

which he was pleased to redeem by his blood,

by bringing an end to war, which destroys all things.

Tire not of praying:

pray for peace, pray for peace,

joy’s true treasure.

Ability to See

Gabriel Josipovici has been to see the exhibition Dürer’s Journeys at the National Gallery. He describes it so vividly I delude myself I’ve seen it, too. Dürer (1471-1528) was indefatigably interested in the world around him, capable at once of global vision and microscopic scrutiny. Speaking of the notebook in which Dürer recorded impressions from numerous journey, Josipovici writes: ‘it is amazing to be able to read, 500 years after they were written, the unguarded comments of a curious traveller whose ability to see had been honed by years of practice.’ The reminder is precious. We may live with eyes wide open, even look feverishly around, without in fact seeing anything. Seeing must be practised. It is an art and an ascesis. It can also be a way of exercising philanthropy. We all know what Josipovici means: ‘At moments, looking at his drawings in particular or reading his Diary, we are pierced with the sharp sense of recognition: “Yes! I know this!”‘ — only we don’t realise until a trained seer enables such epiphanies of self-evidence.

A Bird in the Air

The first time I heard the music of Dhafer Youssef, it brought tears to my eyes. It is unlike anything else, though one senses a kinship with Jan Garbarek. Youssef, who admires Arvo Pärt, has made recordings with Western ensembles of sacred music, such as Jaan-Eik Tulve’s Vox Clamantis (the performance begins at ‘5). When he was a child, in Tunisia, the sound of the chanting of sacred texts awakened his musicianship. He has said, ‘I’ve a relationship with the Qu’ran that is more musical than religious. Religion, for me, is music. With music, there are no barriers.’ That is why it is hard to speak about it, words being circumscribing: ‘You’ve the sense of talking of a bird in the air. Of something which isn’t there.’

You can hear Youssef’s powerful Elegy for my Mother, part of his Bird’s Requiem, here. It impresses me that a YouTube commentator calls it ‘a purely cathartic song’.

Adaptations

The Netflix series Stories of a Generation, prominently featuring Pope Francis, carries precious flashes of insight. As Aldo Grasso remarks, in a column in the Corriere della sera, events and experiences are gently uprooted from their context to become universal allegories.

I have been touched, and inspired, by Carlos and Cristina Solis, a Uruguayan couple who, after fifty years of marriage, decided to take up the tango. It has given their relationship a new dimension. It has helped make profound and life-giving dynamics explicit. ‘Love, as we have experienced it’, says Carlos, ‘is a succession of adaptations from one to the other’ — just like in the tango! He then cites a Snoopy cartoon. Charlie Brown muses philosophically: ‘Some day, we will all die!’ Snoopy answers: ‘True, but on all the other days we will not.’

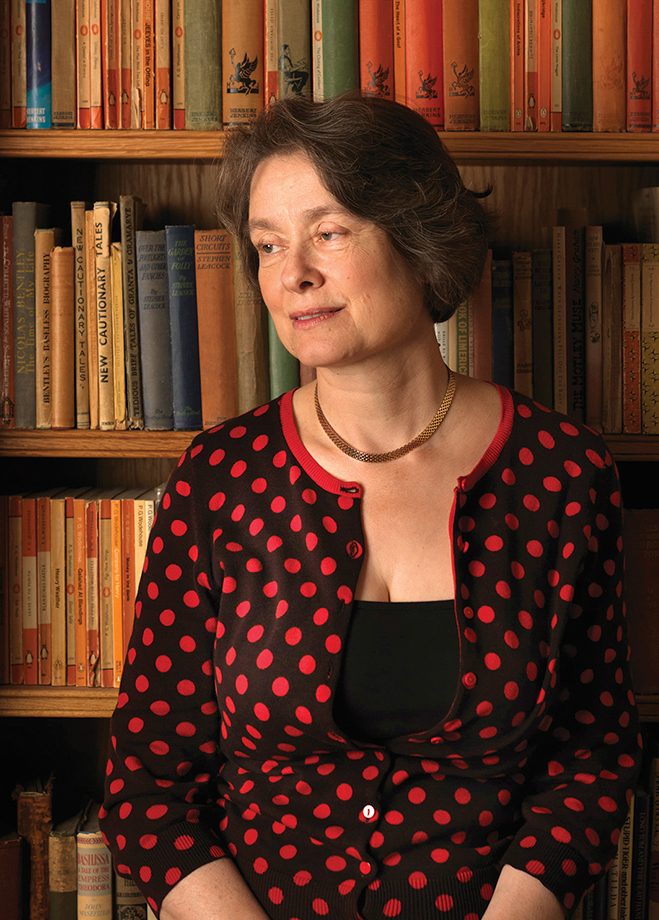

An Essay in Meaning

The voice of Marie Noël, once one is attuned to it, has a timbre quite its own, unmistakeable. Hers is a quiet voice, but one that speaks with authority, a voice that, by virtue of the depths it articulates, opens wide spaces in the reader and there resonates, an accompanying, comforting presence. She, who never left her native Auxerre, once wrote:

‘It was in these depths that the one great journey of my life took place, my descent into the abyss, my adventure, my face-to-face with danger. It was there that I had to go so that I might come back, burdened with the destiny of humankind, instead of staying for ever pure and fast asleep in my little garden with the Cross to keep me safe.’

A selection of Marie Noël’s texts is at last available in English in a marvellous volume presented and introduced by Pauline Matarasso, published today.

Universality

Today is the feast, not just of St Valentine, but of Sts Cyril (826/7-869) and Methodius (ca. 815-885). The two were blood brothers. Their extraordinary career certainly warrants them the title of Patrons of Europe. Alexis Vlasto, citing Zdenek R. Dittrich, calls Methodius ‘the last great figure of the universal church.’ He explains: ‘There had been schisms before; irrevocable schism was still more than two centuries ahead. Yet from the end of the ninth and particularly in the tenth century […], it was scarcely possible any longer to belong indifferently to both East and West. This was due not merely to the gradual estrangement between the churches on matters that touched their doctrine, ritual, customs, and all other aspects, but also, more obviously, to political factors in a Europe that was undergoing a rapid process of crystallisation.’ Right now, political tensions between East and West are crystallised terrifyingly in Europe. All the more reason to strive to restore fractured bonds within our own hearts and between the Churches.

Unravelling

Professor Thomas Fischer, a German judge, has a sharp mind and a pen to match it. He is not one to brush things under a carpet, and no Catholic apologist. I am struck by remarks with which he concludes an essay published in Der Spiegel last week, on the ways in which we, as a society, engage with the legacy of abuse: ‘The Church is subject to the same processes as other structures of external management and power-charged unassailability, which have melted away through globalisation. Communities cease; left are individuals. Responsibility gives way to self-optimisation. External management gives way to loss of direction. The community of God-fearers morphed at first into cosy group therapy, then into provision of customised wellness on demand. One can view this unravelling as the end of the story — or not. But it is unintelligent to surrender, simply, to baffled indignation. Of course the phantom pain is intense. But what holds a promise of healing is not a retroactive balance sheet with regard to enemies long since vanquished, but earnest efforts to create new structures and institutions of trust.’ Certainly the past must be viewed and integrated lucidly; but with a view to restoring community through whole-hearted, prospective conversion, to translate Fischer into Biblical terms.

Satiation

People ask, ‘Where is God?’ They often put the question, it must be said, cavalierly, as if God ought to be a divinity ‘on demand’. This morning’s Vigils reading puts matters in perspective. God’s Wisdom, it tells us, ‘calls aloud in the streets’. God desires to be known – but we do not answer, and instead construct our lives, our world, as if he did not exist, regardless of him. The text from Proverbs 1 goes on: ‘Then they will call upon me, but I will not answer; they will seek me diligently but will not find me. Because they hated knowledge and did not choose the fear of the Lord, would have none of my counsel, and despised all my reproof, therefore they shall eat the fruit of their way and be sated with their own devices.’ When we look at the world as we’ve made it, which makes us so afraid, is this not what we feel: satiation with our own devices?

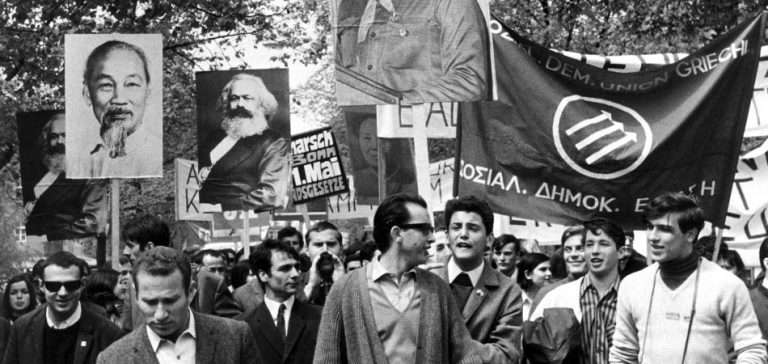

Unchannelled Energy

In an interview from 2018, Bettina Röhl, daughter of Ulrike Meinhof, has interesting things to say about the myth of 1968 as the context for her mother’s revolutionary terrorism. The key figures of the movement, she contends, had for the most part had a privileged youth and were not acting out of WW2-induced trauma: ‘I think this time was full of energy. The West saw an explosion of culture, in music, in fashion. In a misjudgement of what was happening in China, the generation of ’68 confused this remarkable development in the West with the genocidal Chinese culture revolution, envisaged as a model. […] Representatives of ’68 like Gerd Koenen and Götz Aly speak of an unbearable lightness of being. They filled this perceived emptiness with ideologies, with Marx and Mao. This is one point at which I’m inclined to attribute a certain guilt to the then BRD. There was such progress and upward movement, but clearly no spiritual and moral superstructure. Young people are on the search for sense. And so the Revolution became fashionable, and a phantasm.’ Insights to ponder.

Shrunk World

Recent exchanges with friends in Western Cameroon give further evidence of the misery in which the region is mired. In the press, we don’t hear anything about it. The Norwegian Refugee Council has for years listed the civil conflict in Cameroon among the ‘world’s most neglected crises‘. An independent think-tank found last year that reportage on Africa is at best haphazard in Norwegian media. Generally, it is absent. I dare say the following remark can be applied to other countries, too: ‘We observe that the world in many ways has shrunk in the plurality of Norwegian media, and that most resources used to cover international news are directed towards the Anglo-American sphere.’

No one can be constantly alert to all the world’s needs. Still, consistent neglect of certain areas is revelatory. It should cause us to ask questions — not least of ourselves: ‘And I? Am I willing to confront the prospect of a world unshrunk and the responsibility that comes with it?’

Silent Poetry

Lockdown has largely kept people out of museums. In a luminous brief essay, Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery, reflects on the experience of walking round eerily empty rooms listening to the paintings. He writes:

‘A classic early definition of painting is given by Plutarch: ‘Paining is silent poetry; and poetry is painting that speaks.’ He was quoting Simonides of Ceos, a Greek musician and lyric poet of the sixth century before Christ, who wrote verses rich in human empathy. Paintings may make no sound but they have a voice that is able to communicate emotion and meaning across time and space. That is one reason why painting is so important.’

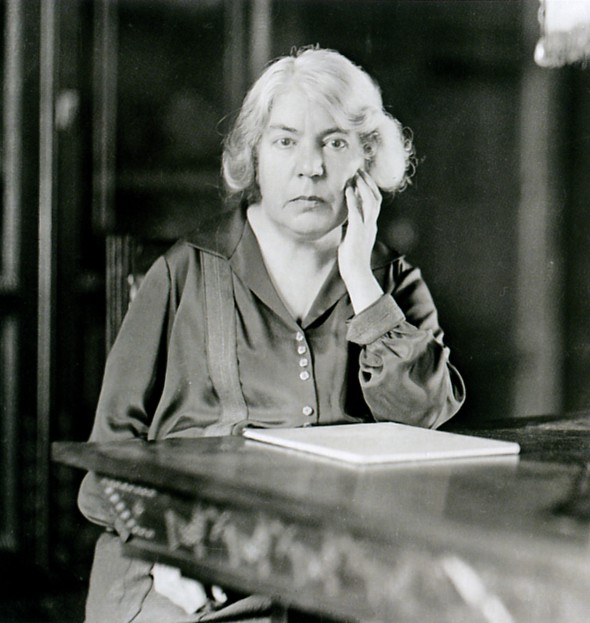

Deledda

I’m not sure why it’s taken me till now to discover Grazia Deledda, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1926, the second woman after Lagerlöf to be so distinguished. I have just read La Madre, which D.H. Lawrence, in a much re-printed preface, rather misunderstood, as far as I can see. ‘The interest in La Madre‘, he wrote, ‘lies in the presentation of sheer instinctive life.’ No, it doesn’t. The novel’s drama adheres in the point of intersection between instinctive and considered choices — which is not to idealise, or simplify, consideration; but to rehearse Deledda’s conviction that instinct calls for reasoned orientation. At the Nobel Banquet, Archbishop Söderblom addressed her: ‘Customs as well as civil and social institutions vary according to the times, the national character and history, faith and tradition, and should be respected religiously. […] But the human heart and its problems are everywhere the same. The author who knows how to describe human nature and its vicissitudes in the most vivid colours and, more important, who knows how to investigate and unveil the world of the heart – such an author is universal, even in his local confinement.’ In Deledda he recognised such an author. He was right.

You can find a decent (Italian) documentary film here.

Agonies

‘Perhaps I can ask you now to reflect on some slightly trickier elements in the book, relating to agonies that come up today about sexuality, gender, abuse, and so on. You are not afraid of tackling them. But the way you’re tackling them is different, I think, from the way they’re often tackled, even by public theologians, because of your monastic perspective. To take issues of gender, first. We know from reading early monastics and ascetics that their lives were often freed up in extraordinary ways from gender presumptions of life in the city or life in the married condition. I think you imply, as I have also in my writing, that this may be a source of fertility, if I may put it like that, for contemporary thinking. Could you say a bit more?’

Thus asked Professor Sarah Coakley in a conversation we conducted recently. You can find the rest of it here.

Brevity

In The Splendid and the Vile, Erik Larson cites Churchill’s famous memo on brevity addressed to Cabinet 0n 9 August 1940. It contains observations one hopes might go viral.

‘To do our work, we all have to read a mass of papers. Nearly all of them are far too long. This wastes time, while energy has to be spent in looking for the essential points.’ Four excellent counsels follow. Then the conclusion: ‘Reports drawn up on the lines I propose may at first seem rough as compared with the flat surface of officialese jargon. But the saving in time will be great, while the discipline of setting out the real points concisely will prove an aid to clearer thinking.’

In October that same year, Churchill wrote to the Secretary of State: ‘The number and length of messages sent by a diplomatist are no measure of his efficiency.’

Nova & vetera

Time and again in salvation history, the impetus for conversion has come from fresh engagement with the past. An emblematic example is recounted in 2 Kings 22. In the reign of Josiah, Hilkiah the priest found the Law of God in the temple. The Law! No one had given it any thought for decades. Yet there is was, making demands at once sublime and shattering. Hilkiah gave it to Shaphan the secretary, who read it to the king. ‘When the king heard the words of the book of the law, he rent his clothes.’ Countless instances of fruitful conversion have begun in this way. The Cistercian movement of the twelfth century is one example, repeated in the seventeenth under Abbot de Rancé.

For more, pursue this link.

To Live a Little

At the beginning of the week I received a communication from a young Syrian, the friend of a friend, trying to find a way of getting his mother and sisters to safety. To explain the urgency, he wrote: ‘Many of my sisters’ peers have been jailed, tortured, raped and slaughtered simply because of their humanitarian work during this immoral and barbaric war.’

Yesterday I saw this heading in a Norwegian newspaper, regarding the lifting of restrictions that will enable sports events to receive more spectators and bars to stay open into the night: ‘Now we can again begin to live a little.’

The contrast between the two perspectives is dizzying. One of the things Covid has revealed is the myopia to which we are all prone. To it, those of us who live in privileged safety easily yield. A year ago, pundits across the globe predicted a new world order of solidarity and compassion. The trouble is, we do not have it in us to pursue such high goals for long. To stick to them, we need to be enflamed by an ideal that brings us out of ourselves.

Natura naturans

The Medievals coined the phrase ‘natura naturans’ to speak of nature’s doing, quite simply, what nature does. The phrase was developed sophisticatedly by Spinoza. Perhaps, though, we might just recover the notion of ‘acting according to nature’ as an active verb?

I am struck by this image of a young tree quietly growing its way through an old garden chair without ruining it. Sooner or later, of course, the manmade object will give way. The seat will erupt. But it will happen gradually, naturally. Even if the chair will have had it, the process will be, somehow, beautiful.

‘If you love a plant’, the Kentucky Shakers used to say, ‘take heed to what it likes.’ We should pay more attention to how nature natures and beware of artifice, not least when we look at ourselves.