Nova & vetera

Time and again in salvation history, the impetus for conversion has come from fresh engagement with the past. An emblematic example is recounted in 2 Kings 22. In the reign of Josiah, Hilkiah the priest found the Law of God in the temple. The Law! No one had given it any thought for decades. Yet there is was, making demands at once sublime and shattering. Hilkiah gave it to Shaphan the secretary, who read it to the king. ‘When the king heard the words of the book of the law, he rent his clothes.’ Countless instances of fruitful conversion have begun in this way. The Cistercian movement of the twelfth century is one example, repeated in the seventeenth under Abbot de Rancé.

For more, pursue this link.

To Live a Little

At the beginning of the week I received a communication from a young Syrian, the friend of a friend, trying to find a way of getting his mother and sisters to safety. To explain the urgency, he wrote: ‘Many of my sisters’ peers have been jailed, tortured, raped and slaughtered simply because of their humanitarian work during this immoral and barbaric war.’

Yesterday I saw this heading in a Norwegian newspaper, regarding the lifting of restrictions that will enable sports events to receive more spectators and bars to stay open into the night: ‘Now we can again begin to live a little.’

The contrast between the two perspectives is dizzying. One of the things Covid has revealed is the myopia to which we are all prone. To it, those of us who live in privileged safety easily yield. A year ago, pundits across the globe predicted a new world order of solidarity and compassion. The trouble is, we do not have it in us to pursue such high goals for long. To stick to them, we need to be enflamed by an ideal that brings us out of ourselves.

Natura naturans

The Medievals coined the phrase ‘natura naturans’ to speak of nature’s doing, quite simply, what nature does. The phrase was developed sophisticatedly by Spinoza. Perhaps, though, we might just recover the notion of ‘acting according to nature’ as an active verb?

I am struck by this image of a young tree quietly growing its way through an old garden chair without ruining it. Sooner or later, of course, the manmade object will give way. The seat will erupt. But it will happen gradually, naturally. Even if the chair will have had it, the process will be, somehow, beautiful.

‘If you love a plant’, the Kentucky Shakers used to say, ‘take heed to what it likes.’ We should pay more attention to how nature natures and beware of artifice, not least when we look at ourselves.

Cîteaux

The Cistercian Order regards itself as having, not one founder, but three: Sts Robert, Alberic and Stephen (not St Bernard!). The Church celebrates the three of them today. On the face of it, the Cistercian project was conservative in scope, retrospective in motivation. Yet its protagonists made ground-breaking innovations. Several trends contributed to this process. One consisted in a systematic appeal to established authorities. Of these, the most obvious was the Rule of St Benedict. The Exordium Parvum provides a succinct account of the manner in which the community approached it. It gives the impression of seamen setting sail on a crisp, clear day, joyfully throwing overboard any ballast threatening to hamper speedy progress. The emphasis is not on grim-faced ‘strict observance’ but on the shedding of encumbrances. Furs, fine frocks and feather beds: let the current take them! Benefices and privileges went the same way.

For more, see here.

Maternity

Not long ago, I had occasion to remark that society increasingly lacks a conceptual framework for behaviour geared towards the supernatural. In Norway, during last year’s lockdown, it became apparent that the law had no way of categorising worship as a distinct form of human activity. It was classed alongside tango classes and bingo nights.

A recent article by Andrea Mrozek observes that the natural, too, is being phased out of public discourse. Referring to a report in The National Post, she notes that female athletes now risk finding pregnancy listed in their contracts under ‘injuries’. Her example comes from Canada. The trend it represents seems universal. Mrozek writes: ‘We don’t have a category for [women having children]. We struggle with how to make special arrangements around it, and frankly, whether to do so at all. Pregnancy and childbearing are confusing propositions today’, increasingly seen ‘as something that inhibits real life rather than contributes to it.’

Dilatatio cordis

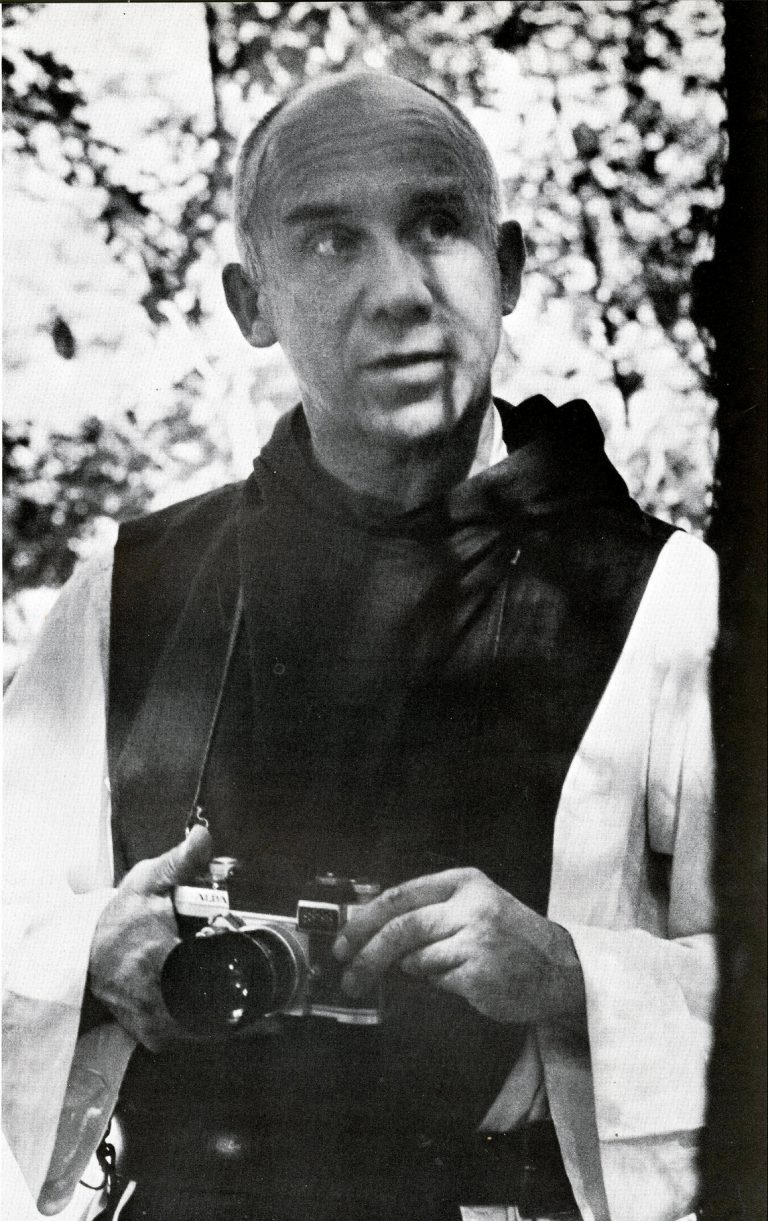

The following observation from Merton’s Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander (1968) is well-known. It is still worth recalling on this last day of the octave of prayer for Christian unity:

‘If I can unite in myself the thought and devotion of Eastern and Western Christendom, the Greek and the Latin Fathers, the Russian and the Spanish mystics, I can prepare in myself the reunion of divided Christians. From the secret and unspoken unity in myself can eventually come a visible and manifest unity of all Christians. If we want to bring together what is divided, we can not do so by imposing one division upon the other or absorbing one division into the other. But if we do this, the union is not Christian. It is political, and doomed to further conflict. We must contain all divided worlds in ourselves and transcend them in Christ.’

One aspect of what St Benedict in his Rule calls the ‘broadening of the heart’, a blessed, painful, joyful business.

R.I.P.

There is nothing to distinguish Thomas (Fr Louis) Merton’s grave from that of scores of other monks buried in the monastic cemetery at Gethsemani except a small accumulation of mementos left by admirers. The white scarf attached to his cross lends his resting place a faintly hippie aspect, which I think he would have enjoyed. Humour is an essential component in Merton’s writings, I see that more and more. He possessed that most precious quality: an ability to laugh at himself – a characteristic shared by most people who take life really seriously.

Merton was buried next to Dom James Fox, his long-time abbot, in some sense his nemesis, but also his brother and friend. If you would like to read my review of Roger Lipsey’s fine book about their complex relationship, you can find it here.

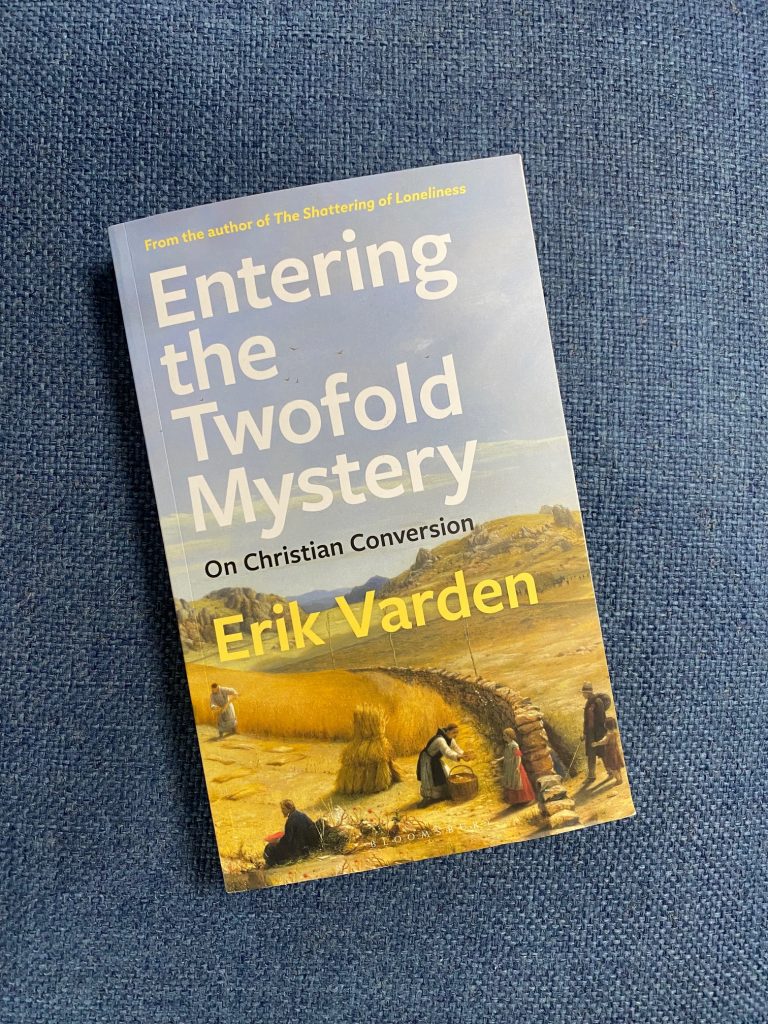

Book Launch

Alone the lover knows. If you love not, I pity you!

The myriad lives will seem to you then but common and cheap

Like the sacred Host to unconsecrated eyes.

Only the lover has eyes to see the splendours of the Other,

With access to the house of twofold mystery:

The mystery of sorrow and the mystery of joy.

Elsa Morante

Entering the Twofold Mystery is published today, the feast of Blessed Cyprian Tansi. If you would like to attend the launch event on 26 January, at which I shall discuss the book with Professor Sarah Coakley, you can sign up here.

Beyond the Subjunctive

‘A certainty dawned: ‘I had not to be nostalgic for what I had been or for what I might have become. Instead I had to love what I was and to seek what I ought to be.’ She abandoned a life’s project composed in the subjunctive mood for one in the indicative. She is emphatic: ‘It was a long journey. Nothing happened overnight. But this is the condition, at once, of redemption and of every battle. […] Forgiveness does not come about in the abstract; it calls for someone to whom it can be addressed, someone from whom it can be received.’

A passage from The Shattering of Loneliness on the testimony of Maïti Girtanner. Here you can find my introduction to a new Italian translation of Maïti’s book-long conversation with Guillaume Tabard, published today.

Not About Seeing Quickly

There’s uncanny prescience in Marguerite Duras’s reflections, recorded in 1985, on life in the 21st century. And she didn’t even know about the internet!

‘I think man will literally drown in constant information about his body, about his physical becoming, about his health, his family life, his salary, his leisure. It is not far from a nightmare. No one will read anymore. They’ll watch TV. There will be televisions everywhere: in the kitchen, in the bathrooms, in offices and streets. No one will travel anymore. It won’t be worth the bother. When you can tour the world in eight days or fifteen days, why do it? In travel, there’s the time of travel. It isn’t about seeing quickly. It’s about seeing and living at the same time. It will no longer be possible to draw life from travel. Still, there’ll be the sea, the oceans — and then reading. People will rediscover that. One day, a man will read. And everything will begin again.’

Unstunted

In a review of The Letters of John McGahern, Emer Nolan, Professor of English at Maynooth, touches on the novelist’s sometimes fraught relationship with Seamus Heaney. Of Heaney she writes, ‘there is little sense in his work of having been stunted or damaged by Catholicism’ – as if this were exceptional. The remark is not malicious, simply bemused. That it should be thus says a lot about Irish Catholicism, indeed Catholicism in general, anno 2022. Examples of dysfunction and destructiveness in the Church are legion, alas; still, to present or tacitly (with guilt-induced breast-beating) to accept them as a norm is irresponsible and false. Over the past few days I have encountered two people who, independently of one another, spoke to me of the ‘explosion of life’ they have found as members of the Church and of the ways in which this explosion bears fruit in joy. I could understand what they were saying. I have known something similar, for which I remain profoundly grateful. It is important to share such experience, to talk about it. ‘Encourage one another!’ (1 Thess 5:11): A fundamental aspect of charity. ‘He who believes in me’, says Christ, ‘out of his heart will flow rivers of living water’ (Jn 7:38). Let the rivers overflow. Share the water generously.

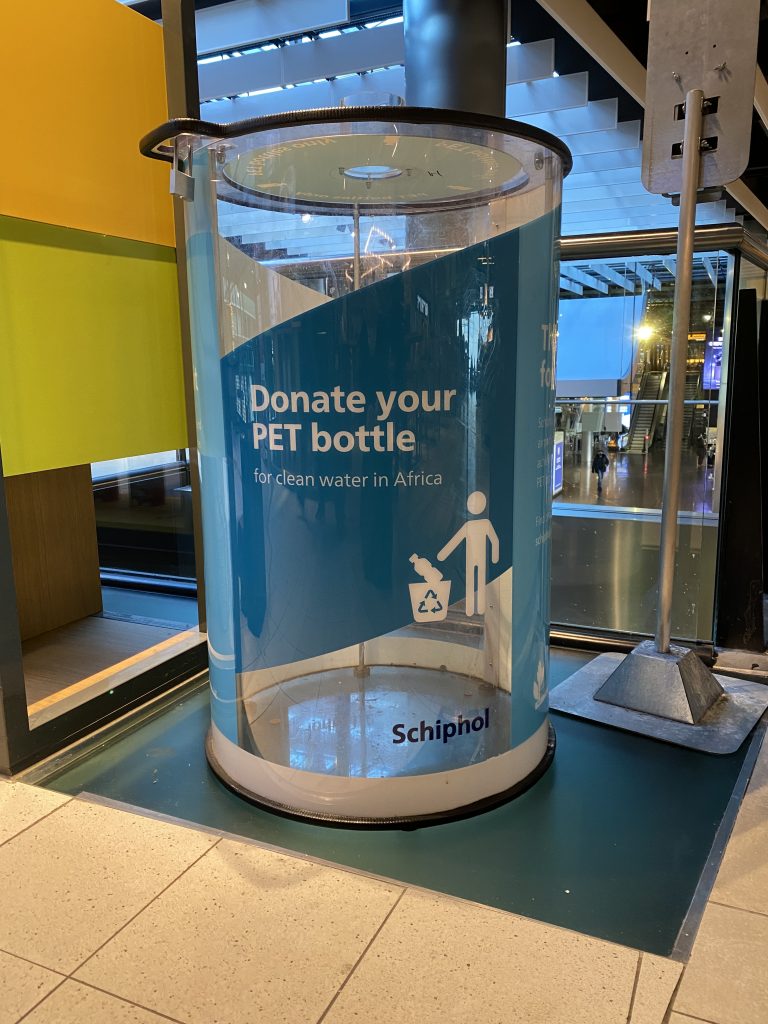

Saving the World

On Monday I stayed in an airport hotel. A note in the bathroom informed me that each re-used towel would help provide drinking-water in the developing world. On Tuesday I passed through Schiphol Airport. A tub invited contributions of PET bottles ‘for clean water in Africa’. I’ve just stepped off a Delta flight, during which the announcement was repeatedly made: ‘Flight by flight we can make a difference. You shouldn’t have to choose between seeing the world and saving it!’ A concern for global welfare is laudable. But surely there is something not right about statements suggesting that I, by chucking plastic into plastic or by taking trans-Atlantic flights, am saving the world? It seems to me a way of anaesthetising conscience, potentially of paralysing real constructive action. I think of a brilliant take on absurdities in self-satisfied aid rhetoric produced by the SAIH in 2012. If you haven’t already seen it, do watch RadiAid: Africa for Norway.

Lifegiving Letters

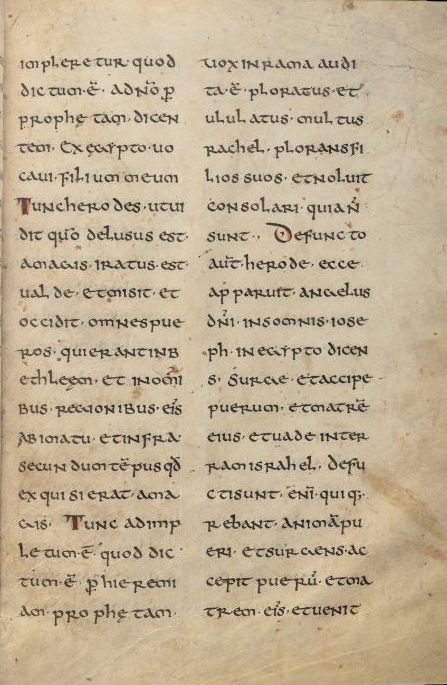

This page is from a manuscript of the Vetus Latina Bible written at the end of the eighth century, probably in Brittany. The text (from Matthew, telling the story of the Holy Family’s journey to Egypt) is eminently legible. What elegance in each letter!

The period from 500 to 800 is often referred to as Dark Ages. After the fall of the Roman Empire, new political and social infrastructure developed, necessarily with a degree of chaos. Much of it was pagan, alien, if not hostile, to the Christian patrimony. During such a time, this glorious artefact was produced to enable the proclamation of hope: ‘Go to the land of Israel! For those who sought the Child’s life are dead.’

What if we, now, were to hold on to the letter of the Gospel with equal reverence, concerned simply to let it speak?

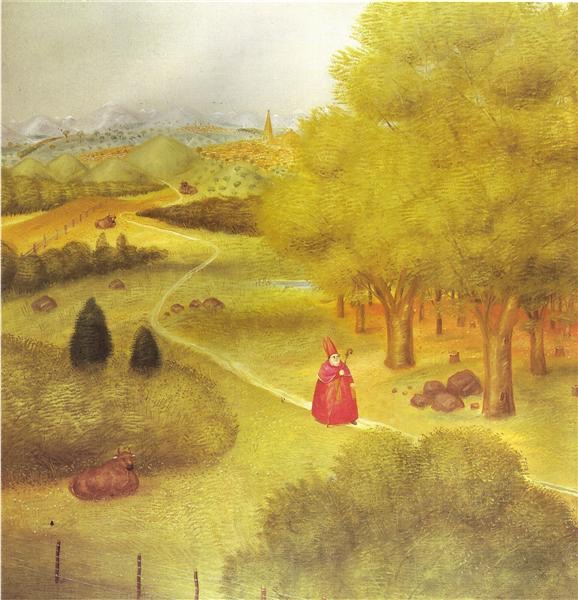

Numquam minus

The art of Fernando Botero can be provocative. It can also illuminate. I am charmed by this ‘Journey to the Ecumenical Council’ in the Vatican Museum. The travelling bishop has no qualms about being visible – that’s the least one can say. He advances with as much of a spring in his step as his girth will allow. His pastoral staff serves a purpose: not a status symbol but an aid to progress through uneven terrain. We may object that he is on his own. Should a pastor not be surrounded by sheep? Well, he is moving between folds: his cathedral’s steeple is seen in the background; the assembly of the council lies ahead. We mustn’t forget the solitude to which a bishop is also called. It is a prerequisite for his ministry of episcopacy, meaning ‘oversight’. His solitude will entail an element of suffering at times, but can also be joyful. One who is truly grounded in the Lord is, to cite Cicero’s phrase, ‘numquam minus solus quam cum solus’ – never less lonely than when alone.

The Fear of God

Right now, when not much works out the way one would expect, one may be forgiven for finding pleasing irony in the liturgical calendar’s announcement that we’re back in ‘Ordinary Time’. In any case, it is good to be given, as a guide to ordinariness, the beginning of Sirach to read:

‘The fear of the Lord is glory and pride, happiness and a crown of joyfulness. The fear of the Lord gladdens the heart, giving happiness, joy and long life.’

Who fears the Lord nowadays? It is an attitude rather out of fashion. This is a pity. What is more, it is a concession to shallowness. What is holy is of its nature fearful simply because it’s categorically different to the stuff of our ordinary lives. If we’ve lost the ability to fear God, we’ve lost the ability to know God as God. And so it is no wonder that people discard the spectre that remains as an irrelevance.

Freedom

In an important book, Dom Dysmas de Lassus, the current prior of La Grande Chartreuse, asks:

‘Isn’t this one of the most surprising aspects of the spiritual life: the ever fuller discovery of the extent to which God, for being our creator, is free in our regard from any desire to assume power and control?’

The extent of our freedom!

You can find a discussion of Dom Dysmas’s book, which analyses what may happen when freedom is put to bad use, here.

Beyond

Today’s collect speaks of salvation proceeding radiantly with a view to bringing about a sunrise in our hearts ‘ever to be renewed’ (ut nostris semper innovandis cordibus oriatur). Our heart’s craving for infinity, its insatiable hunger for super-substantial nourishment, is magisterially affirmed in Fides & Ratio, n. 17.

‘The desire of knowledge is so great and it works in such a way that the human heart, despite its experiences of insurmountable limitation, yearns for the infinite riches which lie beyond, knowing that there is to be found the satisfying answer to every question as yet unanswered.’

A sense of being darkly imprisoned in restraint can reveal itself blessed if I choose to seek freedom and light ‘beyond’. The trouble is, we easily begin to feel comfortable, and safe, in captivity, especially when we’ve designed the prison ourselves.

True Honour

While out on a long drive, I listened to a podcast of Melvyn Bragg’s In Our Time dedicated to Thomas Becket. None of the participants, specialists all, seemed to consider it possible that Becket’s mature recalcitrance may have been based on sincere conviction. The idea that faith might be, or become, the defining reality of a person’s life was not entertained. Such a priori scepticism on others’ behalf is bound to make for a shallow reading of history, and indeed of the present. Jean Anouilh, whose play inspired the 1964 movie Becket with Burton and O’Toole, was nearer the mark when he put this prayer into the newly consecrated archbishop’s mouth: ‘I gave my love, such as it was, elsewhere. […] Please, Lord, teach me now how to serve you with all my heart, to know at last what it really is to love, to adore, so that I may worthily administer your kingdom here on earth, and find my true honour in serving your divine will.’ As Henry II remarks with a mixture of disdain and awe later on, when Becket’s position is fixed: ‘Here he is, in spite of himself.’

Duplicity

Asked by the TLS to name his book of the year, William Boyd plumps for James Hanning’s life of the super-spy Kim Philby. He remarks:

‘What continues to intrigue about Philby after all these decades is his astonishing ability to maintain his double-life with such devious aplomb for so long. It showed a true, virtuoso dedication to the the art of duplicity, if such a thing exists.’

I think it does. There’s no joy in it, and we all have it in us to practise it, even if not to the level of virtuosity. Hence the abiding force of the Biblical injunction to cultivate an undivided heart.

2022

I would have liked to invite all readers of the Notebook to a decent New Year’s lunch. Alas, the logistic challenge is too considerable. As an alternative solution, I offer you this recording, made at Verbier in 2002, of Bach’s Concerto for Four Pianos BWV 1065 interpreted by Argerich, Kissin, Levine, and Pletnev. A YouTube commentator has written: ‘If aliens were to stop on earth and ask what our civilisation is like, I would show them this concerto.’ Vox populi, vox Dei.

Thank you, known and unknown friends, for your interest and digital companionship. I wish you a blessed and happy year. As Dag Hammarskjöld wrote in his diary at the beginning of 1953:

‘Night is coming on.’

For all that has been – Thanks!

To all that shall be – Yes!

+fr Erik

Hope

Amid the excesses, and frequent banality, of seasonal decoration in our society of affluence, I was moved by this image from a youth prison in Northern Cameroon. The embellishments were overseen by a man serving a very long sentence, a man who once said: ‘You have to accept who you are. Once you do that, peace is possible. In prison I have become a man. My desire is to enable each of my comrades, too, to say with conviction, ‘I am a man’, to help them understand that they possess a freedom of self even in prison.’ One way of doing that is by creating something gratuitously lovely, the way God did when he created the world, and each of us. The friend who sent me the photograph remarked: ‘There is an irony in the paper ornaments becoming so many lights with the glow of the prison search lights beamed onto them. A confirmation that beauty can be retrieved wherever there is the faith to do so.’ Where there is beauty and faith, hope can be reborn. Blessed are those who kindle it.

Right & Wrong

I always try, on this day, to re-read Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral. As a student I had a walk-on part in an amateur production. The advantage of having seen – and heard – a play many times, is that salient phrases stick in one’s mind. Timeless is Thomas’s observation:

The last temptation is the greatest treason: / To do the right deed for the wrong reason.

More than ever, however, I am struck by the warning that follows:

Servant of God has chance of greater sin / And sorrow, than the man who serves a king. / For those who serve the greater cause / may make the cause serve them.

Which may God forbid.

Pelagianism

The term ‘pelagianism’ is bandied about quite a bit, often cryptically. A helpful application is one made by Benedict XVI when he spoke about ‘Bourgeois Pelagianism’. According to Tracey Rowland, commenting on it in a recent interview, it refers to ‘the mentality that Christ does not expect us to be saints. It is sufficient that we are decent types who recycle our rubbish, donate a few dollars to charity, and refrain from murdering and raping our neighbors or stealing their property. The mentality is that Christ was not really serious when he said that we must be perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect.’ She generalises the notion of the ‘bourgeois’ (broadly understood as ‘keen on upward social mobility’) by identifying a ‘bourgeois Christianity’, which ‘does not fight on sacramental ground. It does not fight at all. It simply goes in search of Christian-friendly elements of the Zeitgeist with which it might identify and market itself.’

And so one is presented with plenty of scope for new year’s resolutions.

Freethinking

At the age of 92, George Bernard Shaw pronounced this considered judgement upon his friend, the formidable (and admirable) Abbess Laurentia McLachlan of Stanbrook: ‘though you are an enclosed nun you have not an enclosed mind’. Twenty-four years earlier, in 1925, when Shaw had contended that the Catholic Church has not space for Freethinkers, Dame Laurentia objected: ‘I said that to my mind no thinker was free as a Catholic – the limitations being in the direction of good sense and ensuring right thinking; it is not freedom to be able to think contrary to objective truth.’

About to make profession, at nineteen years of age, Dame Laurentia and her novice companion received a note from Dom Laurence Shepherd, a monk who had done much to affirm the community’s contemplative vocation: ‘Tell them they must be saints. They must be grand Benedictines of the seventh century.’ A call heeded.

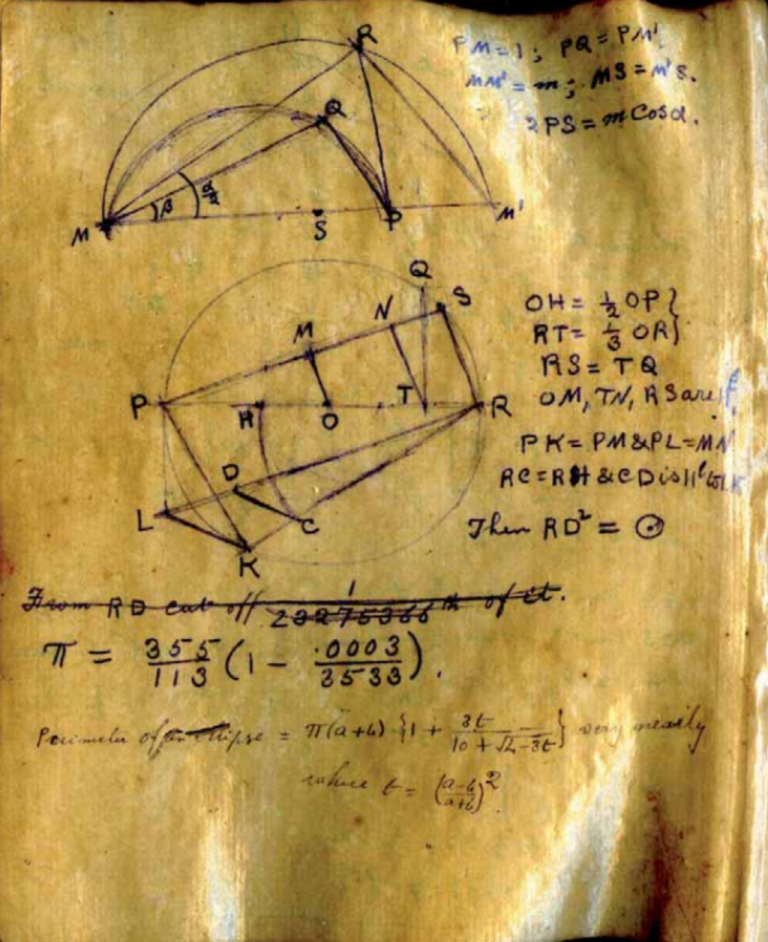

Ramanujan

Matt Brown’s 2015 film about the great mathematician, ‘based on true events’, is based on a fair amount of imagination, too. The result is a picturesque but somewhat unsatisfactory yarn full of facile stereotypes, with more than a passing resemblance to Slumdog Millionaire. There are good lines in it, though, as when Hardy says, in an early encounter, ‘You, just as Mozart could hear an entire symphony in his head – you dance with numbers to infinity’; then, later, while promoting Ramanujan’s candidature as a Fellow of the Royal Society: ‘We are merely explorers of infinity in pursuit of absolute perfection: we do not invent these formulae; they already exist and lie in wait.’

And, of course, there are Ramanujan’s own words of certified authenticity: ‘An equation for me has no meaning unless it expresses a thought of God.’