Tromsø in Advent

EWTN’s Colm Flynn has paid a pre-Christmas visit to Tromsø, producing a lovely reportage broadcast today. You can find it here. The strong invocations of the final days of Advent, ‘Let your light shine upon us!’, ‘Come, do not delay!’, resound with special force in the Polar Night, which can occasionally reveal displays of spectacular colour. Holy Writ speaks of a playfulness embedded in the structure of creation: ‘When he fixed the foundations of earth, then was I beside him as artisan; I was his delight day by day, playing before him all the while, playing over the whole of his earth’. Sometimes, it takes the darkness of night to awaken to this, to learn anticipation – and rejoicing.

Utopias

It is fascinating and uncanny to re-read an essay Joseph Needham wrote for Scrutiny in 1932. It begins like this: ‘‘Utopias’ writes Prof. Berdiaev, in a passage which Mr. Huxley chooses for his motto ‘appear to be much more realisable than we used to think. We are finding ourselves face to face with a far more awful question, how can we avoid their actualisation? For they can be made actual. Life is marching towards them. And perhaps a new period is beginning, a period when intelligent men will be wondering how they can avoid these utopias, and return to a society non-utopian, less perfect, but more free.’ Mr. Huxley’s book is indeed a brilliant commentary on this dismally true remark. It is as if a number of passages from Mr. Bertrand Russell’s recent book The Scientific Outlook had burst into flower, and had rearranged themselves in patches of shining colour like man-eating orchids in a tropical forest. Paul planted, Apollos watered, but who gave the increase in this case, we may well ask, for a more diabolical picture of society (as some would say) can never have been painted.’

Conclave

So I did go to see Conclave. As a cultural phenomenon it shows, like Nanni Moretti’s Habemus Papam from 2011 (a much cleverer film), the fascination exercised by Catholic rituals and processes on a world professing indifference to religion. The photography is good. The script is flat. The characters lack depth. The allegiance to stereotypes is heroic. I didn’t find the film offensive; it isn’t interesting enough to offend. If I left the cinema feeling dejected, it was for another reason: Edward Berger’s effort shows how sterile talk of religion becomes when faith is absent from it. Dan Hitchens has suggested, in a thoughtful review, that Conclave points beyond itself. I fear my response is more hopeless. I found the film leaden, with no intimation of flight. It is an implicit exposé of the third commandment, for what happens when the name of the Lord is taken in vain is not necessarily blasphemy but pointlessness.

Holy Globalism

In the curious mishmash that makes up the York Art Gallery, where some very fine pieces hang among some very indifferent pieces, I came upon this portrayal of St Birgitta, one panel of a diptych in which she is flanked by, of all people, St Anthony the Great. The ensemble was produced by Maso di San Friano about 1565 for a church near Florence. A fourteenth-century Swede in the company of a fourth-century Egyptian, removed from Renaissance Italy to post-industrial York. Just behind the Art Gallery stands St Olav’s church, dedicated in 1055. Just 25 years after Olav’s death, his cult had spread to the north of England. The communion of saints presupposes and nurtures a global view of history, and of mankind, that lets us draw lines and see connections across the pedantic boundaries we draw to enclose ourselves reassuringly in too narrow categories of belonging. We need this broader perspective now, when in many places portcullises are lowered, bridges burnt.

Tenderness

I was sitting on the airport shuttle early this morning when I read the second reading of vigils, astounded by the immediacy of words written nearly a thousand years ago by that great man and monk, Anselm of Canterbury. How tenderness carries across the centuries! The vocative diminutive ‘homuncio’ and twice repeated ‘aliquantulum’ are eloquently encouraging. ‘Come, little fellow, rise up! Flee your preoccupations for a little while. Hide yourself for a time from your turbulent thoughts. Cast aside, now, your heavy responsibilities. Put off your burdensome business. Make a little space free for God; and rest for a little time in him. Enter the inner chamber of your mind; shut out all thoughts. Keep only thought of God, and thoughts that can aid you in seeking him. Close your door and seek him. Speak now, my whole heart! Speak now to God, saying, I seek your face; your face, Lord, will I seek. And come you now, O Lord my God, teach my heart where and how it may seek you, where and how it may find you.’

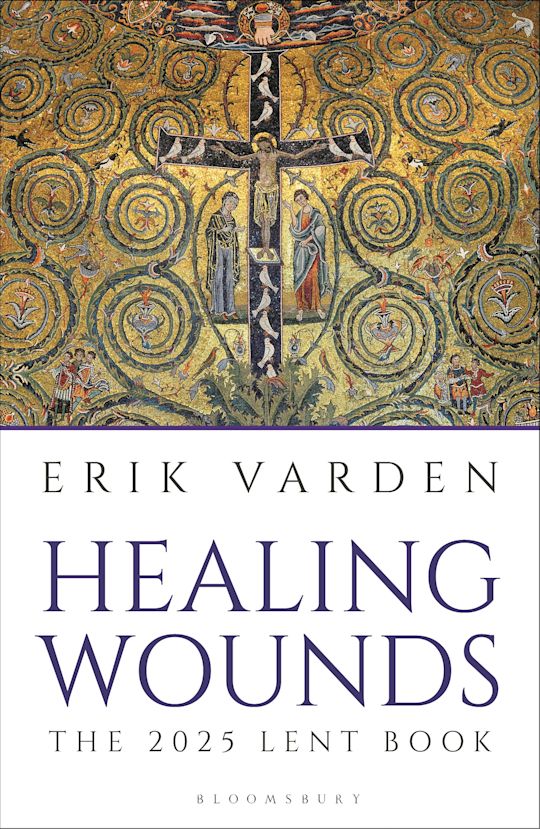

Healing Wounds

‘There is a tendency in Christian devotion to prettify, even to idealise, wounds. This tendency is perverse. Human nature, created in the image of God to be like God, is made for wholeness. Here and now we inhabit a world that is wounded, groaning in pangs of deliverance. We are wounded, subject to the anomaly which Scripture calls ‘sin’, an existential wasting-sickness. Sin leaves its mark on our spirit and on our body. It can paralyse our will or lead it astray. To be fully human is to own this state of affairs. It is to be reconciled to loss and the inevitability of death. But it is no less to remember that our woundedness is of time, and that time will pass. The Christian Gospel envisages the passage from a frank acknowledgement of wounds to the prospect of definitive healing. It proposes a vista of transformation, ‘a new heaven and a new earth’ where ‘death will be no more, mourning and crying and pain will be no more.’ There, the first things will have passed. The first things, though, must happen first.’ From Healing Wounds, published today.

Die Manns

The docudrama is a tricky genre. The dramatic component easily comes across as a series of ornamental vignettes jarring with or romanticising the documentary. Life is mostly duller than drama; so we are left feeling cheated, confronted with something that is neither quite real nor quite satisfying our thirst for fantasy. Heinrich Breloer’s Die Manns is an exception to this rule. True, Thomas Mann and his gifted entourage were not a ‘normal’ family: in their case realism was fantastic. There is at the same time a narrative rigour to the drama that presents a credible portrait, not only of a clan, but of a world before, during, and after World War II subject to cataclysmic change. It is an unsettling and appropriate film to watch again now, with so much coming undone. The serene commentary of Elisabeth Mann Borgese adds a note of paradoxical hopefulness. Marcel Reich-Ranicki called Die Manns a high point of German cinema. I’d say that is no exaggeration.

Iron Age Words

I recently learned that Fr Paul Mankowski would advise people to pray the Divine Office by giving them this recommendation: ‘It’s good to have Iron Age words in your mouth every day.’ His phrase has been ringing in my ears, echoing with truth. There’s something about the taste of substantial ancient utterance that trains one’s palate to appreciate excellence and identify bosh, an exercise which, practised daily, may actually train me to swallow the latter before I am tempted to articulate it. This morning at Lauds, I savoured the phrase: Ego et anima mea regi cæli lætationes dicimus. Literally: ‘My soul and I speak rejoicings to the king of heaven’ (Tobit 13.7). There’s no dualism here, but recognition that I’m often enough at odds with myself. Am I where my soul is? To let myself be challenged by that question is, I think, an excellent way to prepare for Christmas.

Oneself in a Word

I am charmed and inspired by the answer Einar Økland gives an interviewer in last week’s Dag og Tid:

– If you were to sum yourself up in a word, which would it be?

– Colon [:].

–???

–A colon has something on either side of it, open to what comes in and what goes out. But it is an articulation made in retrospect. One doesn’t know what one takes in until one releases it, until afterwards. An alternative answer could have been ‘full stop’. A full stop has no extension and can be both a beginning and an end.

Poetry

A contribution to the Books of the Year supplement in The Tablet of 30 November 2024:

There is something remarkable going on in the poetry of Father Paul Murray, a crystallisation progressing from one volume to the next, though without lessening his poems’ characteristic earthiness and intimacy. Light at the Torn Horizon contains many fine pieces in a register stretching from the playful (‘Canticle in Praise of Punctuation’) to the deeply serious (‘To a Friend Dying’). I have read it with reverence, attention, and gratitude.

A Good Man

Thinking of Mount Melleray, I recall with veneration a monk who served as prior there at a difficult time, a deeply good man whose funeral I was privileged to celebrate: ‘For anyone inclined to think that a monk’s dying to the world is a life-denying, fearful, glum affair, Brother Boniface provided a startling corrective. What a cheerful, warm-hearted, hospitable man he was! As Mount Melleray’s porter he exercised for decades a ministry of welcome. A brother who worked with him has told me he never saw Boniface turn away a person in need. That is a noble legacy. Brother Boniface received all comers kindly. He practised the asceticism of suspended judgement. Not that he was gullible. In fact, he was very shrewd. But he refused to condemn another. As a result, he was a vessel of comfort for many. He gave fresh heart to the hopeless, showed the way to the lost. Gifted with wonderful patience, he knew how to listen. Having listened, he would speak, but not much. His essential message was conveyed simply by his presence.’

No Abiding City

The news of the Cistercians’ departure from Mount Melleray has caused many reactions. The abbey has played a key role in Ireland’s Catholic – and secular – history. I have just re-read an elegiac essay John Waters wrote ten years ago after a visit to the place, conscious of witnessing something precious passing away: ‘It strikes me forcibly that, even if we are barely aware of their existences – even if we scorn their sacrifices – the silent prayerful presence of these men here is somehow vital to our very human continuance. I don’t mean just that they pray for us, but that the sense they give us of something to be believed in so unconditionally – that, even as we scoff, this somehow allows us to continue inhabiting what we think of as the ‘real’ world, in much the way that we once partied all night, knowing that our staid parents slept fitfully at home, hoping we would make it back safe with the dawn.’

Infant of Prague

It seemed eminently meaningful to find myself, in the evening of the feast of Christ the King, on my knees before the Infant of Prague. The aesthetics of the statue and its shrine will appear differently to different people, but that is beside the point: what the monument expresses is that God, to become man, became a child. Dom Porion has written: ‘God made himself a child to heal our useless fears and to inspire us with confidence; for fear, lack of trust, and timidity constitute an ancient and grave illness that affects us all to a greater or lesser extent.’ This is true. There is a further dimension to this image. Having been made in Spain it was brought to Prague in rough conditions: it lost its hands. A Carmelite praying before the statue seemed to hear it say: ‘Give me hands and I will give you peace.’ He promptly restored them. Countless people have since found peace in the statue’s presence. Of course, there is also a parable in the story: each of us is called to be Christ’s hands in this world, instruments for the good he wishes to accomplish. Caritas Christi urget nos.

Cecilia

‘Cecilia’s Christian witness caused scandal in a city still largely pagan. She was arrested, then condemned to suffocation in the baths. When the city’s prefect heard she was still alive after 24 hours, he ordered decapitation. The henchman struck thrice, unable to sever the head from the trunk. Roman law did not permit a fourth attempt. He left Cecilia bleeding, therefore. She lived on for three days. Then she died, and was buried by Pope Urban. This story, told in ancient chronicles, was confirmed by observation in the jubilee year of 1600. During restoration works at the abbey of Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, on the site where Cecilia’s family had held its titulus, the martyr’s remains were found. Not only were they in a state of incorruption. The twisted position of Cecilia’s head also corresponded exactly to the story of failed execution. The find was a sensation. Swiss guards had to be brought in to control the traffic of pilgrims wanting to pray in the physical presence of one of Rome’s most beloved saints.’ From Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses.

Poison

One of the papers I look at each morning is the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, a good old-fashioned continental broadsheet with a deserved reputation for serious, well-researched journalism. Even here one senses a change of tonality these days. I have been struck to find, over little more than 48 hours, three front-page headlines that cry out: ‘Poison!’ The contexts were various, applying first to a political party (the AfD), then to the culture of victimisation, then to Platform X. The matters in hand are causes for concern, that is true. But what does it do to public discourse when bastions of measured analysis yield routinely to hyperbole? What does it say about journalism that such easy recourse is had to the semantic register of toxins? It goes beyond my competence to attempt the psychoanalysis of a newspaper. But it seems to me these questions are worth asking. The task of the press is surely to articulate problems so that these can be addressed, not just to cry wolf.

Creating Order

One of my favourite books by Thomas Merton is his Seeking Paradise: The Spirit of the Shakers. The Shaker village of Pleasant Hill is unfar from Gethsemani. Engaging with the history of the place and its deep motivation, he was struck by parallels with monastic life. He summed up his findings in this little book, illustrated with his own photographs. We are treated to a precious collection of Shaker apophthegmata, like this one: ‘We are not called to labour to excel, or to be like the world; but to excel them in order, union, peace, and in good works – works that are truly virtuous and useful to man in this life. All things ought to be made according to their order and use.’ What a revolution might ensue in a time in which ‘manufacture’ has become an all but meaningless term, if this principle were heeded here and there. The Shakers also liked to say: ‘If you love a plant, take heed to what it likes.’ That counsel is transferrable to many aspects of living and relating.

Wounded Lion

The story of St Jerome and the lion reached its canonical form in The Golden Legend. It must have circulated long before, but its textual origin is shrouded in mystery. In the medieval telling, a lion turned up at Jerome’s monastery in Bethlehem one might. The brethren were aghast, but Jerome saw that the beast needed help. Its paw was wounded, pierced by a thorn. The saint extracted it, and the lion was delighted. It ‘ran joyously throughout all the monastery and kneeled down to every brother and fawned them with his tail, like as he had demanded pardon of the trespass that he had done’. The motif has been amply reproduced in art. I recently saw this charming depiction on the Lübeck altarpiece in St Nicolaus’s church in Tallinn. St Jerome looks as crusty as by all accounts he was, yet what precision and gentleness in his surgery. The thorn has become a nail fit to run through a portcullis. The fierce lion stands before us like a cub. The lesson is clear: sometimes we are fearful of things that are in themselves innocent; at the same time, small stings can have disproportionate impact.

Discovery

In an interesting interview already ten years old, Tamara Rojo speaks of her first experience of ballet, at the age of five. She’d been brought into the school gymnasium out of the cold while waiting for her mother to pick her up. A dance lesson was going on: ‘There was this quietness and harmony, it felt perfect, like a world I’d never seen. I didn’t want to leave. When my mother finally came, I said: ‘But we need to stay and watch this to the end, whatever it is!’ Because I didn’t know what ballet was. I didn’t understand that ballet was a performance.’

The precocious, mysterious insight small children can have regarding their call, the way they must follow. It calls for reverence.

Perspective

One day it’s enough,

you feel, to view the world

through the common lens

of history, content

with no vision wider

than that of the obvious.

Next day, caught by

a tumult of longing, you search

among the straw and

chaff of things for the golden

corn of meaning.

From Fr Paul Murray’s Light at the Torn Horizon.

Down the Mountain

A rereading of Mann’s The Magic Mountain leads George Packer to a conclusion that seems to me exact: ‘In driving our democracy into hatred, chaos, and violence we […] grant death dominion over our thoughts. We succumb to the impulse to escape our humanness. That urge, ubiquitous today, thrives in the utopian schemes of technologists who want to upload our minds into computers; in the pessimism of radical environmentalists who want us to disappear from the Earth in order to save it; in the longing of apocalyptic believers for godly retribution and cleansing; in the daily sense of inadequacy, of shame and sin, that makes us disappear into our devices. The need for political reconstruction, in this country and around the world, is as obvious as it was in Thomas Mann’s time. But Mann also knew that, to withstand our attraction to death, a decent society has to be built on a foundation deeper than politics: the belief that, somewhere between matter and divinity, we human beings, made of water, protein, and love, share a common destiny.’

Stranezza

Ostensibly the account of a writer’s block endured and overcome, Roberto Andò’s film La Stranezza develops into a kind of parable. The intensely particular becomes an image of universals: the film is really about what it means to be human; what is more, it is a humanising film. I watched it during a transatlantic flight, in the kind of half-stupor such passage induces, and am astonished to find that a number of scenes and dialogues not only remain fresh in my mind but present themselves as carriers of happiness. The ‘strangeness’ to which Luigi Pirandello is subject (a circumstance well known from the author’s life, dramatised with imaginative freedom) is at once constricting and liberating, enabling insight and representation without precedent, born of cordial encounters. Life as theatre: this is what the story is ultimately about. Gently and companionably, Andò prompts a question, addressed to each of us: And you, are you really playing your part?

Religion of the Self

I think of an essay Vito Mancuso published on 13 June last year, a day after the death of Silvio Berlusconi. Mancuso reflected not so much on the man as on the phenomenon he embodied, il berlusconismo, instantiating a global tendency that puts ‘the primacy of personal success before any kind of outreach to others, establishes applause as the measure of anything’s value and transforms citizens into spectators.’ The piece goes on: ‘You see, in earlier times one could imagine the transcendent in various ways: in the classical sense of Catholicism and other religions; in the socialist and communist sense of a classless, finally just society; in the liberal, republican sense of an ethical state like the Prussian one lauded by Hegel; in the sense of right, incorruptible personal conscience as in Kant’s moral philosophy; and in many other ways besides. All of them, though, have this in common: the conviction that something exists that is more important than the self, before which the self must quieten itself and serve. From the beginning of mankind, the concept of God has stood, exactly, for the vital sense according to which there is something more important than my self, my power, my pleasure […]. The triumph of berlusconismo represents the breakdown of this spiritual and moral tension. In as much as it constitutes a religion of the self, it proclaims the opposite: nothing matters more than me.’ Where this tendency is prevalent, what chance has any meaningful notion of society or of the common good?

Fragile Unity

The vocation of Abraham, our father in faith, was synodal. Having heard God’s call, ‘he took his wife Sarai, his brother’s son Lot, the persons whom they had acquired in Haran’, and set forth to go to the land of Canaan. At first it went well enough. As long as the journey’s destination is remote, susceptible of idealisation, synodality does not pose major challenges; travellers envisage the nature of the trip as they please. When the journey’s end approaches, when questions arise of dividing territory, tensions arise. The possessions of Abram and Lot were such that ‘the land could not support both of them living together’ . They split. ‘Separate yourself from me’, said Abraham, ‘if you take the left hand, then I will take the right’. This story helps us relinquish simplistic notions of synodality. If one does not have the same finality in mind, the same image of a paradise to restore, a centrifugal force will make itself felt. Unity, ever vulnerable, will then be liable to break.

The Crow

A fresh encounter with a movement from Schubert’s Winterreise becomes for Daniel Capó an occasion to reflect on the underlying malaise of our time. He writes, ‘The question of art is, above all, one that probes each of us and opens the future to new paths. Schubert’s romanticism, with its burden of anguish, translates into our era with all the hallmarks of the twentieth century: mass destruction, totalitarianism, the indiscriminate use of propaganda, rock music… No society can emerge unscathed from these experiences, nor can any recreation we attempt of past or present. Like the wanderer who sings in Winterreise, we journey in search of an authentic home. Civilization thus springs from a simple gesture repeated through time: welcoming hands and recognizing eyes that preserve us from dissolution.’ You can read his essay in its entirety here.

Angelus

Early this morning, standing at the bus stop in the rain, I suddenly heard the Angelus from St Olav’s cathedral pour out over the cityscape in sonorous benediction. Little gives me as much comfort as the sound of the Angelus bell. It is a marker of civilisation, a proclamation at once discreet and majestic of life’s purpose and sense, direction and finality, spreading its beneficial reach to those, too, who have not the slightest idea of what it stands for. I think of a few lines by Jehan Le Povremoyne set to music by Vierne: ‘The Angelus sounds across my city still asleep; the Angelus of bells in honour of Mary. See how the night flees. How joyfully the Archangel’s greeting resounds upon my city still asleep. As the doe’s fawn behind the hill, the sun will leap forth.’