Not Ungiven

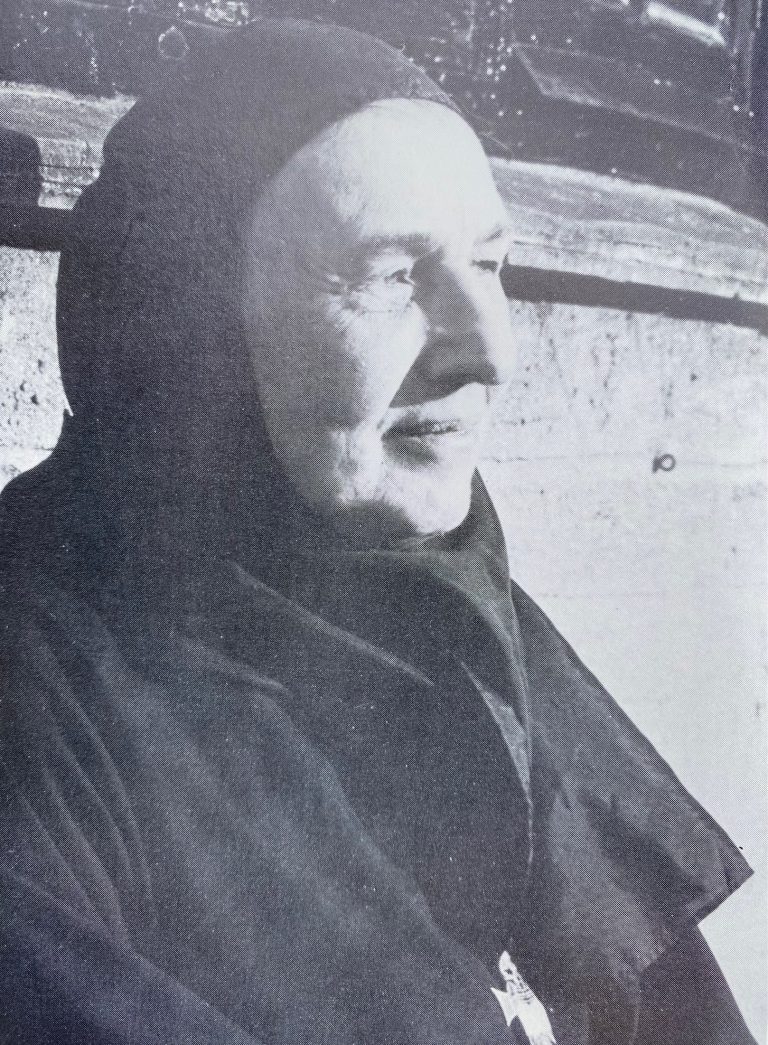

Anyone who has touched the mystery of Alzheimer’s whether personally or indirectly knows the mystery, often the sheer terror, it represents. Mother Agnes Day, for many years abbess of Wrentham, found a way of articulating this experience from within, beautifully. Rereading her poems, I am touched anew, not least by this text, which speaks of trial embraced as part of a total, unflinching, serenely trustful monastic oblation:

O Lord, here is my candle. Blow it out.

I am no better than my father in my fear.

I ask no more of words than YES.

But while I still have consciousness

I would not slip away ungiven!

Her sisters said of her: ‘It would be hard to describe how much Mother Agnes meant to our community or how good she was.’

Brittleness

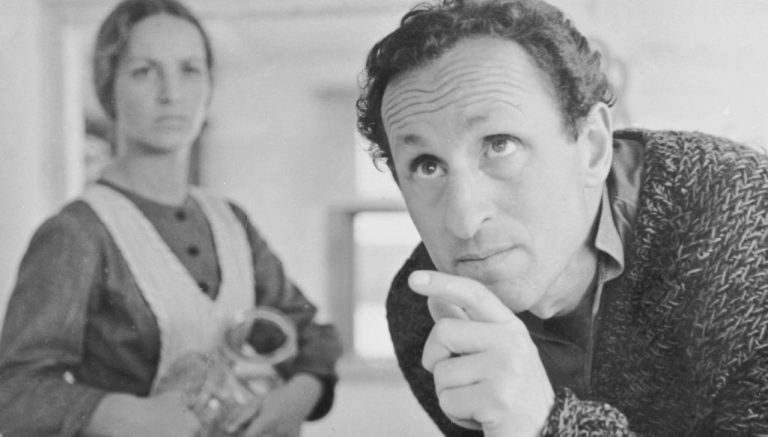

When an international readership thinks of Norwegian literature, the names that impose themselves will be Ibsen, Undset, Hamsun – and now Jon Fosse. Not many people these days read Tarjei Vesaas. He is, however, a giant, long recognised as such. From the end of the Second World War he was serially nominated for the Nobel Prize. Friends alerted me long ago to Witold Leszczyński’s 1968 adaptation for the screen of Vesaas’s The Birds under the title Żywot Mateusza. Only last week did I watch it. It is an extraordinary movie, at once realistic and poetic, exquisitely filmed, with a remarkable performance by Franciszek Pieczka. Vesaas had a rare ability to render the brittleness of life as being not menacing but beautiful. Leszczyński communicates this insight reverently, filling his work with tenderness notwithstanding the tragic ending. Corelli’s Concerto Grosso op. 6 no. 8 punctuates the scenes. It gives one a jolt at first, but the choice is inspired. You can watch Żywot Mateusza with English subtitles here.

Keep Jogging?

In an early account of the life of St Jane Frances de Chantal, we find her speaking to her sisters of the Visitation about the love of God. God, she assures them, yearns to pour it out on us. But we, in order to receive it, must be ready. This requires on our part an ‘unconditional consent’ to God’s design, a complete and irrevocable surrender of self ‘from the moment we give ourselves up wholeheartedly to God until the moment we die’, a sacrifice quite as real as that of the martyrs. She commented: ‘But this goes for generous hearts and people who keep faith with love and don’t take back their offering; our Lord doesn’t take the trouble to make martyrs of feeble hearts and people who have little love and not much constancy; he just lets them jog along in their own little way in case they give up and slip from his hands altogether; he never forces our free will.’ This prospect faces me with an immense choice to be made each moment: will I spend my Christian life just pottering along with a divided heart, a divided love, making forays into the woods of self-will, or will I wholeheartedly follow the One who calls, really desiring to be with him where he is?

Monastic Schools

Over the years I have encountered many graduates of the Cistercian Preparatory School in Dallas. Without exception they speak of their school, even decades after leaving it, with deep affection and gratitude. That is not the case with every school. Visiting Dallas this week, I experience the genius loci that inspires the life of the vibrant monastic community and their educational apostolate, springing from the charism and call of their Hungarian mother house. A précis of their history can be found in this brief film about Dom Denis Farkasfalvy, longtime headmaster and abbot (cf. Notebook entry for 15 February 2023). I am heartened to see the brethren’s commitment to their heritage as well as their generous, intelligent investment in their work. At the moment, in Europe, most monastic schools are shutting down. For this there are several reasons, some deeply tragic. Yet I cannot help thinking: in the light of a general breakdown in schooling, considering parents’ and children’s mistrust of conventional schools, in response to the growing thirst for a new Christian humanism, this monastic apostolate does not only have a venerable past, but an exacting and potentially promising future.

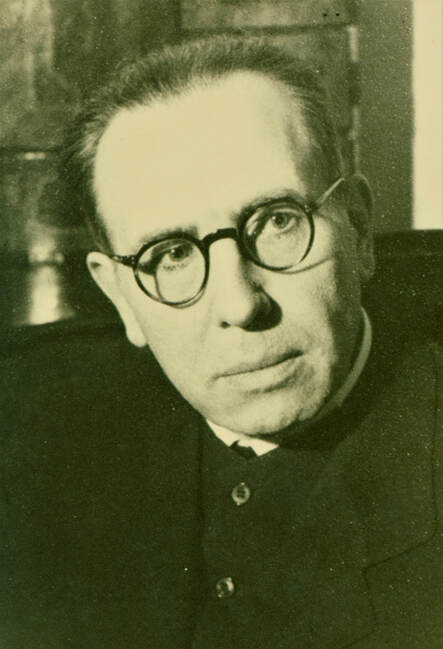

A Confessor

Dom Wendelin Endrédy, abbot of Zirc, is one of our century’s great confessors of the faith, imprisoned and tortured by Hungary’s communist dictatorship for over six years. His memoirs are an exceptional Christian testimony. They end thus: ‘My thoughts repeatedly return to the prison; I relive each of its scenes time and again. I cannot help it. The prison transforms a human being in some fundamental way. The first thing I tell myself in retrospect is that for no earthly treasure would I give away the sufferings of these six years. I was given an immense amount of gifts. I finished an education, graduated and now I hold a diploma on which it stands written: an improved human being. I would have been a bad student of physics if I had not seen in my prison-life a basic law of modern atomic physics proven: “All matter is ultimately light.” […] The second conclusion I come to is this: every bit of rubbish, no matter how riff-raff and valueless it is, can become light, eternal light, if God’s Sun shines on it and releases it from the burden of the horror of evil. This is why I am unable to feel hatred toward those who have hurt me, those who tormented me. I hate none of these evil men. I like to pray for them from the bottom of my heart, asking that they may convert and become good human beings.’

Cannibalism

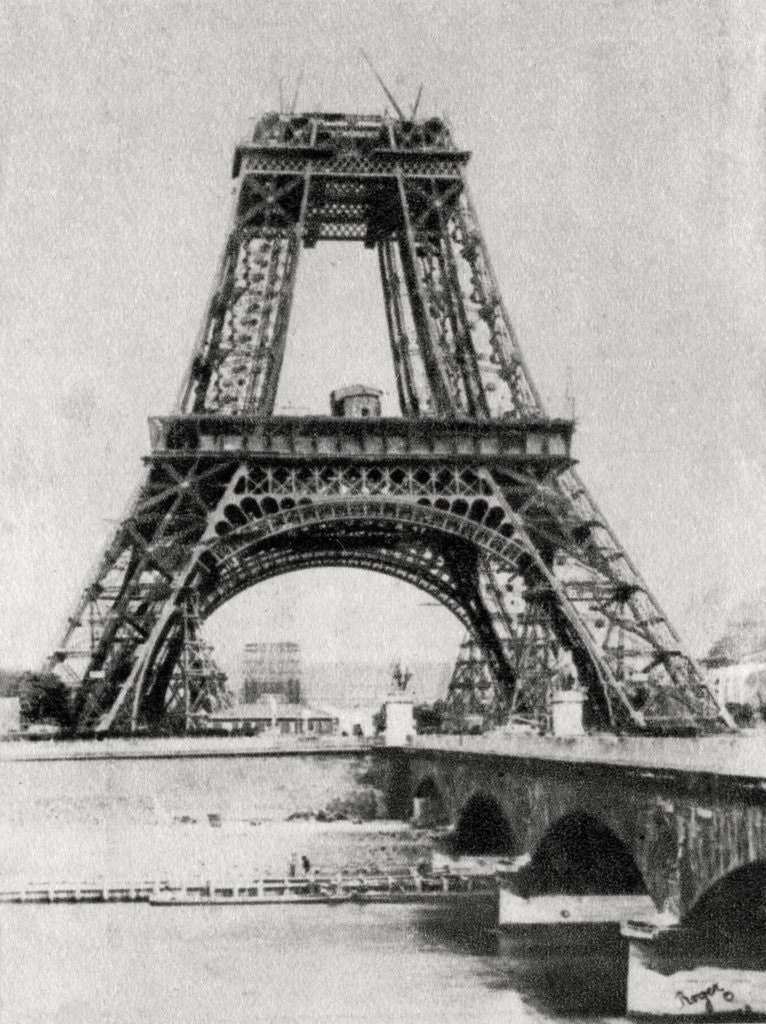

In a piece in America today, the feast of the Transfiguration, the Jesuit Anthony R Lusvardi comments incisively on the Olympic opening ceremony. Going beyond hurt exasperation (he admits that his first response to the most offensive scene was a yawn) he invites us to set out from what we have seen to reflect on the society we live in, which require a creative, deliberate response from us. He concludes: ‘Years ago, when visiting Paris — as beautiful as its reputation is — I remember going to the Eiffel Tower and, when I got up close, thinking, “It’s impressive from a distance, but up close it’s just a lot of steel girders and empty space.” What the organisers of the Paris Olympics put on display was their empty space — the vacuousness of the secular cultural project. In the end, that vacuousness is what makes the mockery of Christianity at the Paris Olympics so dull. Even with all the resources at their disposal — mounds of corporate funds and French tax euros — all they could do was cannibalise Christian forms.’

Old and New

Nini Roll Anker’s affectionate book My Friend Sigrid Undset (1946) contains the famous quip from 1915, to the effect that ‘at least the Roman Church has form; it does not appear insulting to one’s intelligence.’ ‘Poured out of the form of the Roman Church’, Undset told her friend, ‘all of Christianity seems to me like a failed, burst omelette.’

Less well known is this remark from 1920: ‘I have the sense that I am seeking my sea legs all alone in a world full of currents, and I long for a fixed point of reference that doesn’t alter or slide eel-like away; I long for the old Church on the rock, which has never claimed that a thing is good because it is new or good because it is old, but which, on the contrary, takes for its sacrament wine, which is at its best old, and bread, best fresh.’

St Olav’s Way

This year’s pilgrimage to Trondheim for Olsok has caught the attention even of international media.

Here you can find an article by Bénédicte Cedergren for the National Catholic Register. She interviewed some of the youth who walked on foot to the sacred sites associated with the martyrdom of St Olav. One of them told her: ‘To be a Catholic is to not be alone.’ Fr Adan Pawlaszczyk wrote a fine piece about the celebrations in the Polish magazine Gość Niedzielny. Here is a slide show on the instagram page of Vatican News. The Italian site Il Timone picked up a story about the pilgrims’ Mass on Snøhetta. And here is an account of how an EWTN editor experienced these intense days of prayer and fellowship, of solemn liturgies and joyful meals, of gratitude for the gift of faith generously shared.

Unhistorical

With fascination I have read and re-read the inaugural lecture CS Lewis gave in 1954 on taking up the Chair of Mediaeval and Renaissance Literature at Cambridge. What he says about the descriptio temporum, the notional division of epochs, is intriguing. Essential, though, is his remark about historical knowledge itself: ‘I do not think you need fear that the study of a dead period, however prolonged and however sympathetic, need prove an indulgence in nostalgia or an enslavement to the past. In the individual life, as the psychologists have taught us, it is not the remembered but the forgotten past that enslaves us. I think the same is true of society. To study the past does indeed liberate us from the present, from the idols of our own market-place. But I think it liberates us from the past too. I think no class of men are less enslaved to the past than historians. The unhistorical are usually, without knowing it, enslaved to a fairly recent past.’ That insight provides a key to much that is going on, and not going on, at the moment – in the Church as in politics.

One Man Band

I do not normally use the Notebook for mere announcements. But I will make an exception to explain a circumstance that may forestall frustration. A number of readers have written to complain that they have not found translations of some recent texts. I apologise for this. The reason is simple: CoramFratribus is entirely a one man band; and since my days are, alas, no exception to the 24-hour norm, I am sometimes unable to keep up. I do endeavour to provide bilingual versions of all material, but it will sometimes take me a little time.

Thank you for your understanding! And thank you for your interest in the site.

+fr Erik Varden

Chimera

It’s been a long time since I last left the cinema feeling so transported I felt the need to hold on to something — an umbrella, a wall, a supporting hand, anything — on stepping out onto the pavement. In her much-hailed Chimera, Alice Rohrwacher creates a near-perfect illusion, fiendishly difficult to categorise. I suppose that’s in the nature of an illusion. The film is an exercise at once in realism and subversion. It made me think of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. Or perhaps it was just the response it evoked in me that called forth the association. On the face of it, Chimera is about crooks and buffoons. There is, however, an intensity of credible life in it that makes it enchanting. One emerges feeling intensely alive. There are plenty of jokes. Good ones. There is Sophoclesian seriousness. Performances are fantastic, some by amateurs, others by legends. Chimera is about so many things that to talk about a plot is impossible. Yet it is linear and coherent. It is at once italianissimo and universal. I loved this film without quite being able to say why. I can only recommend it.

It Takes a Poet

Eight decades ago, while the Second World War was raging in a state of frenzy, William Francis Jackson Knight wrote in his still very readable book, Roman Vergil:

‘The Romans were hard, cynical materialists. Bloodshed was what you saw and the news you heard. Shameless exploitation was accepted as normal. We could say the same of our time. But just occasionally, even to contemporaries, a window is opened on to the soul of an age. There are hard things, and there are soft things, which last and in the future have their command. These are the things which it takes a poet to see and say.’

Commensurate

Recently, during a long drive, I listened to Yo-Yo Ma being interviewed on Desert Island Discs. He speaks of growing up with a recording of Leon Fleisher playing Brahms’s First Piano Concerto. Anyone who has heard that recording will know what an impact it makes. Only upon watching Nathaniel Kahn’s fifteen-minute video portrait Leon Fleischer – Two Hands did I discover that the great pianist spent much of his life, on account of a subtle neurological condition, with a substantially incapacitated right hand. The drama that represents for a pianist is overwhelming; the lucidity and grace with which he dealt with it are inspiring. Fleisher remarks: ‘There was a lot of despair and misery and unhappiness. But there were commensurate ecstasies. And you can’t really expect to have one without the other.’ On the whole, he says, he wouldn’t have changed anything in the way his life turned out. In this there is a parable – worth watching, and thinking about.

To Be Decent

In a judicious essay in today’s Klassekampen, Carline Tromp reflects on Iris Murdoch’s novel Under the Net, which she inherited, apparently together with Murdoch’s complete oeuvre, from her mother. With regard to the protagonist she writes: ‘One feels like crying out: Everything isn’t about you – pull yourself together! Jake is as inconsistent as a snowflake, as brittle as a biscuit. Other people are extras, antagonists, at best little helpers. The reasons why Jake has turned out this way are complex. The war is just ten years back, one can only speculate. But Murdoch’s point, the way I read her, is that this is of no importance. No circumstance absolves you from the responsibility to make an effort to become a decent human being.’ This is well observed. I am less convinced when Tromp notes that Murdoch provides the help one needs ‘to find out alone what is right’ after having ‘thrown off God as a moral compass’. I hope that, one fine day, she will read and comment on Murdoch’s The Bell.

Mary Magdalene

After the burial of Jesus, his Apostles hid behind locked doors ‘for fear of the Jews’. What about Mary Magdalene? Was she not afraid? It would be odd if she wasn’t. As the known follower of a branded man, she was at real risk. She hurried to the tomb ‘on the first day’ not because she was fearless, but because she knew a desire that made fear seem insignificant. So intense was her longing to be with Jesus, to grieve by his side, that she cast caution to the wind. That energy of love qualified her to be the first witness to the resurrection. It made her, as the Greek liturgy has it, ‘Apostle to the Apostles’. From this we can draw a practical lesson. When we are fearful, the best remedy is not always to deal hands-on with our trouble, apt to entangle us in confusion and self-pity. We emerge victorious not by fighting darkness but by fostering our desire for light. And the light will kindle in us that love which casts out fear. Out of hopelessness we shall hear the voice of Jesus speaking our name. We shall know him to be alive and true to his promise: ‘See, I am with you always!’

Reaching the Young

In a recent gathering in Greece, my friend Father Theodosios Martzouchos, longtime protosynkellos to the great Bishop Meletios of Preveza and now parish priest in the city, reflected on the urgent challenge of passing on the faith to the young in today’s weird, fast-moving world. He spoke of faith and doubt: ‘Faith in God is a kind of struggle. Faith is not unprovable metaphysics, it is a constant overcoming of both reason and lack of reason. That is why it never becomes irrefutable certainty, it becomes irrefutable doubt. It is not a frenzy of self-convincing reason, but an awakening of reason’s doubt of itself. Doubt is the dawn of faith and the criterion of its value-quality.’ He remarked that the Church often tells the young they ‘are the Church of tomorrow, while in fact they are the Church of today! The Church wants to accompany them for what they will become; while they want to be taken into account for what they are now!’ I am grateful to Father Theodosios for sharing this insightful talk with us. You can read it here.

Guts Into It

I love this documentary portrait of Jini Fiennes, novelist, essayist, painter, photographer, so talented in so many ways, who nonetheless, whenever she had to fill in her profession on a form, always wrote just, ‘mother’. She would tell her seven children, in pursuit of some goal or other, that they’d ‘got to get their guts into it’. She herself lived viscerally, though at the same time with consummate intelligence. She turned a childhood marked by absences and an early breakdown into tasks to be fulfilled creatively, with precision and beauty. She demonstrated by her life a most important point: it is possible, by perseverance and grace, to pass on graciously to others what one has not received. In a poem she spoke of her freedom being ‘spilt and poured’ into others’ needs, though because the spilling and pouring were desired ends, her freedom was not ultimately compromised. It grew. It became love.

Bishops’ Sermons

I am made thoughtful by a remark of Christopher Isherwood’s cited by Zachary Leader in a review of Katherine Bucknell’s new life. It concern the turning of Isherwood, ‘an unlikely convert’, to Vedanta. He explained it thus: ‘My prejudices were largely semantic. I could only approach the subject of mystical religion with the aid of a brand-new vocabulary. Sanskrit supplied it. Here were a lot of new words, exact, antiseptic, uncontaminated by association with bishops’ sermons, schoolmasters’ lectures, politicians’ speeches.’ Isherwood, as Leader remarks, did not have much of a predisposition for the chastity and asceticism Vedanta presupposes; but that is by the by. His point is an important one, it seems to me. At the best of times, bishops’ sermons have been charged with the irreducible newness of the Gospel, a resonance audible, for example, in the Ambrosian texts the breviary has given us this week. When did they turn tedious? How to convey Christ’s perennial novelty today? The question is an essential one.

Desire

For Vigils today, on the feast of St Bonaventure, the Church gives us a passage from his Itinerarium mentis in Deum. A passage reads like this in the breviary: ‘For this passover [into life in Christ] to be perfect, we must suspend all the operations of the mind and we must transform the peak of our affections, directing them to God alone. This is a sacred mystical experience. It cannot be comprehended by anyone unless he surrenders himself to it; nor can he surrender himself to it unless he longs for it; nor can he long for it unless the Holy Spirit, whom Christ sent into the world, should come and inflame his innermost soul. Hence the Apostle says that this mystical wisdom is revealed by the Holy Spirit.’ That is already wonderful. But it becomes even more striking if you look up the original and realise that the word translated ‘innermost soul’ is medullitus, which means ‘in his marrow’, i.e. in his most physical interiority; and that Bonaventure’s word for ‘longing’ is desiderare. Why do we shy away from and paraphrase the Fathers’ (and Scripture’s) stress on the physical and affective dimension of the spiritual life?

On Priesthood

I recently met a priest who had attended February’s Roman conference on ongoing formation for the clergy. He said that by far the most valuable contribution, rapturously applauded, had been that of Mother Martha Driscoll. Having listened to Mother Martha’s talk, I can see why. She said among other things, having exhorted priests to become contemplatives: ‘Being contemplative doesn’t mean being a saint. Ordination does not automatically confer sanctity. In fact, contemplatives are more aware of themselves as sinners in constant need of mercy. The love of Jesus is light and so he shows us our darkness – our faults, limitations, selfishness, our inner divisions and pride. He leads us into self-knowledge so that we can be more and more emptied of self, more and more united to Him so that it is no longer I that live but Jesus who lives in me. […] Priests need the joy of deep understanding of their priesthood as the fulfilment of their heart’s desire. Christ came not only to reveal the Father but also to reveal us to ourselves. If they know their identity in Christ, they can help others to find theirs.’ This is an important talk. You can find it here, from ’47:50.

Sven Åge Varden RIP

Maybe there is only a strip

of shadow between their world

and ours? Maybe they are

as near to us now as the tall

handsome ferns in the garden

or as the sounding river

or as the light in the darkening sky

or as the balm of jasmin

in the air, or as those lifting

sparks, the tiny fires of

glow worms glimpsed, half-glimpsed

in the bonfire-smoky dusk?

Summer Break

I am taking a vacation.

CoramFratribus will have a break, too, but will be back in a couple of weeks.

Happy summer! And thank you for your interest in the site.

+fr Erik Varden

God’s Pleasure

Today’s Vigils reading from a treatise by St Cyprian tells us: ‘We should know and remember that when we call God our Father, we must behave as children of God, so that whatever pleasure we take in having God for our Father, he may take the same pleasure in us.’ I am brought to think of an observation the Reverend John Ames makes in Gilead: ‘Calvin says somewhere that each of us is an actor on a stage and God is the audience. That metaphor has always interested me, because it makes us artists of our behaviour, and the reaction of God to us might be thought of as aesthetic rather than morally judgemental in the ordinary sense. How well do we understand our role? With how much assurance do we perform it? […] I do like Calvin’s image, because it suggests how God might actually enjoy us.’ A wonderful perspective.

Vastness

Valerie Stivers on how Kristin Lavransdatter made her discover that Catholicism was something quite other than she had imagined: ‘Religious people, places, and traditions are not there to condemn Kristin for breaking the rules—though she has broken them. For her sins, she is mostly punished by life. The religious people, places, and traditions are there to meet her in the pain of her struggle and offer things: forgiveness, wisdom, tradition, community, advice, punishment when needed, endless fresh starts. I had always imagined the Church as a distant and cruel regulatory body, and suddenly I saw it as Undset did, as the place you turn with the whole unregulated mass of your life—as the only place large enough for it.’

Having Time

I am often helped by something Mother Maria Gysi wrote in a letter to Professor A.H. Armstrong more than fifty years ago:

‘I already begin to feel that I have time again. Time that I never had for six years. Time is so little connected with actual work. It is something quite different, I believe. It is the absence, or relative absence, of pressure on the mind.’

This rings true. The secret is to learn to resist the pressure, or to let it, I suppose, just pass through one.