Example

Only in Hammerfest have I had the experience of seeing wild reindeer from an airport carpark. The Catholic parish in the town is the world’s northernmost. The climate is challenging; though much depends on your point of view. The locals say: ‘We’ve nine and a half months of winter, but apart from that it’s non-stop summer!’ The first Catholic Church was dedicated here in 1878, part of the extraordinary North-Pole Mission headed by Baron Étienne Djunkowski. What were its principles? They were various; but one can get a sense of which were most effective. The other day I met a nonagenarian, wonderfully youthful parishioner who is a fourth-generation Hammerfest Catholic. What, I asked, had caused her great-grandmother to convert at a time when Catholicism was held in suspicion and snowball fights erupted between Catholics and Laestadians? Her answer was clear: The example of the Sisters of St Elisabeth, who made this patch of land their own and loved it, who poured themselves out to help people during a time of famine while nurturing a deep life of prayer, maintaining the church as a place of beauty in a setting of harshness. The lesson is perennial.

Life & Calculation

Needed construction work in the cathedral complex in Tromsø has ground to a halt because a pair of black-legged kittiwakes (Rissae tridactylae) have built a nest in a corner of the yard. The kittiwakes are a protected species. The city authorities were clear: no human activity is permitted to disturb their habitat until the pair’s young have left the nest. It’s a nuisance from a practical point of view; I’d like to see the work completed. It is also something of a peril: the birds are protective of their territory, swoop low with menacing cries when one goes in and out, and practise precision bombing. At the same time there is something beautiful in this situation. The providence of two menaced, exposed birds have arrested the strategic planning of serial human agencies, leaving us all in anticipation of their freckled eggs hatching. The priority of life, be it fragile, wins out in an unequal combat with cool calculation. In this, may there be a parable.

Voice to Word

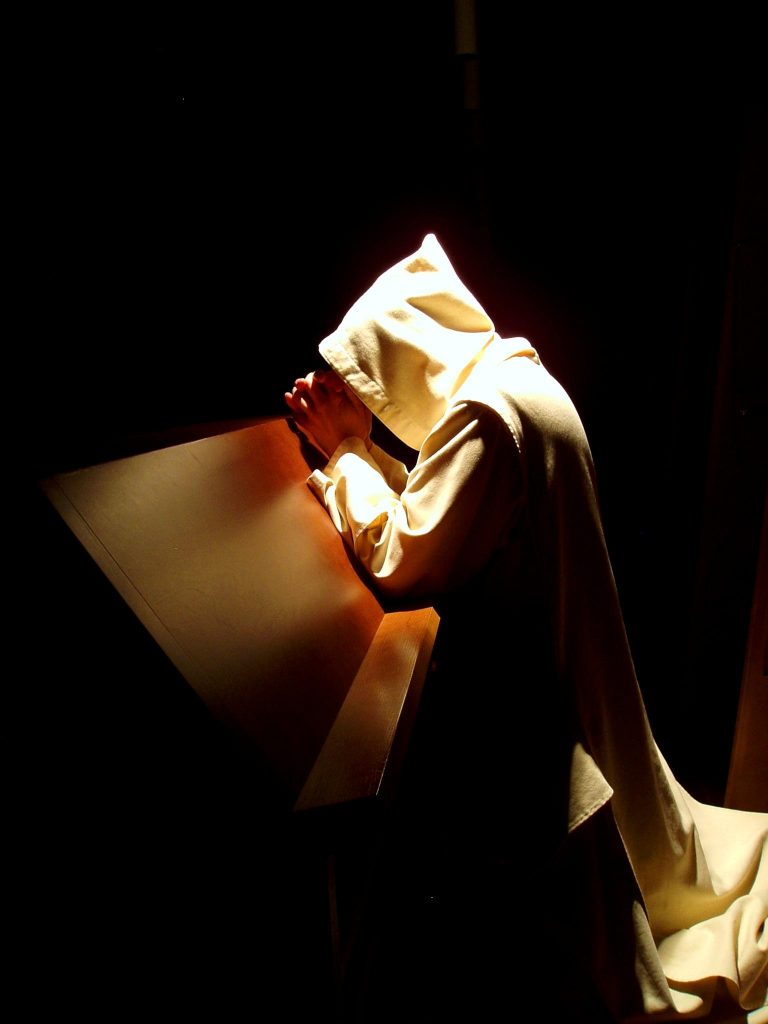

Though I have read them countless times, the Letters of St Ignatius of Antioch always reveal something new. For Vigils today, the Church gives us a passage in which Ignatius exhorts the Christians of Rome not to canvass for his release and instead to let him face martyrdom (Rom., II)): ‘I shall never have a better opportunity of reaching God, and you will never have the opportunity of performing a better act than now, by keeping silence. If you remain silent, I shall become the word of God [λόγος θεοῦ]; but if your love of my physical life makes you speak, I shall be nothing but a voice [φωνή]. Grant me nothing more than this: that I should be poured out to God, while an altar is still ready for me.’ Ultimately this is the trajectory we must all follow: from being a mere voice to becoming a substantial word, a process that will be accomplished by means of oblation.

Suffusion

Gathered with a group of friends for a seminar on Ida Görres, I am affirmed in my conviction: hers is a crucial voice for the present moment (see Notebook 1 February, 23 June and 17 September 2023). About the Church she writes: ‘The strangest creation of God, so unique in kind, so large, so contradictory, so colourful that no single person can take stock of her and figure her out, and certainly no outsider can ever take her all in, let alone understand her and judge her. Only she herself can do this, comprehending herself in faith, endlessly considering herself in her faithful theology, looking at herself through her mystics, loving herself in her children. Only the believer as the cell of this body, embedded, suffused with her life-process of knowledge, faith, love, participates also in her consciousness and in the spirit in which she understands herself.’ In terms of a contemporary register of terms, such suffusion would seem to be a sine qua non for synodality.

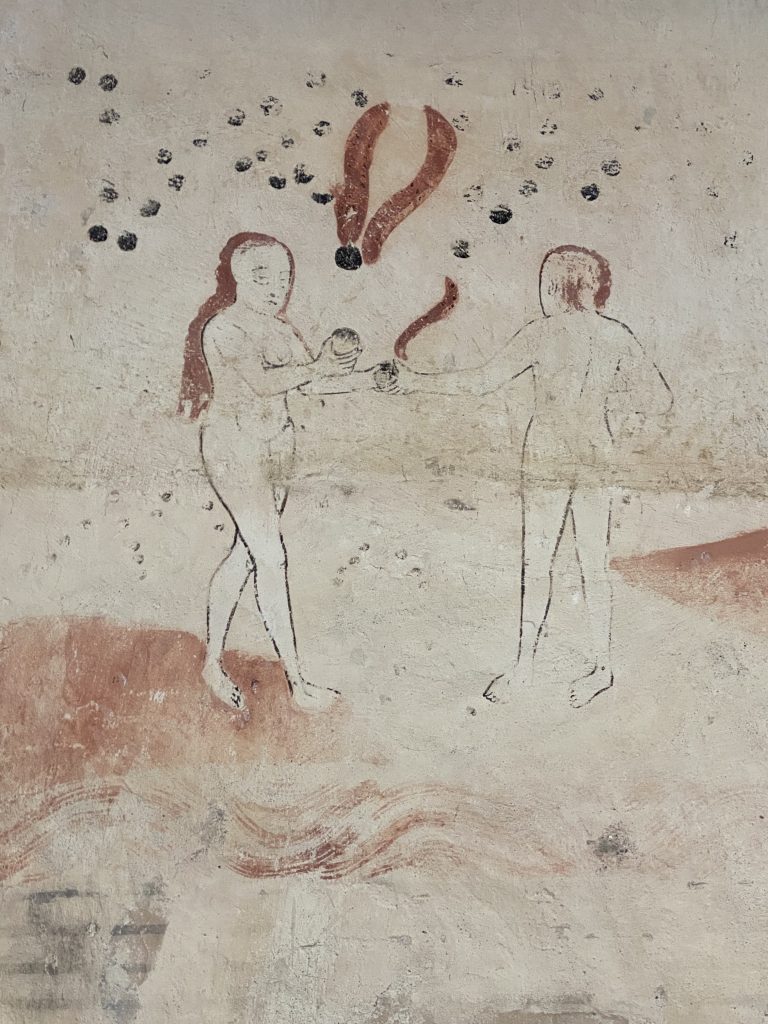

Aversion of the Gaze

This sixteenth-century mural in the twelfth-century church of Moster shows the drama of the fall. Man and woman, created to face one another fearlessly with love, can no longer look upon one another. Adam’s face is turned away, invisible. His betrayal has reduced him to something less than the prosopon as which he was created to subsist. Impressive is the energy of the serpent whose disturbing coils, for being interrupted by whitewash, testify to a determined purpose to undermine relationship.

‘When Scripture speaks of the origin of sin, the first casualty is the natural, free relationship between the sexes. The fall lets Adam and Eve know what it means to be ‘cut off’. They no longer find themselves in one another. They hide. They are ashamed.’ From Chastity.

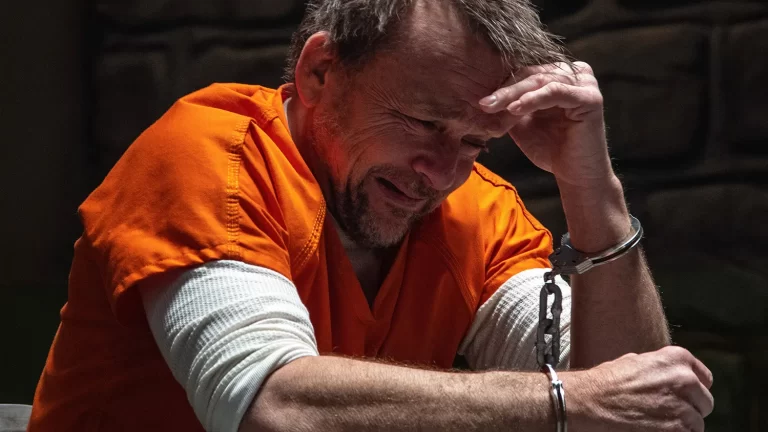

Nefarious

A seminary rector recommended Nefarious to me. I am glad he did — I probably shouldn’t have seen it otherwise, it being advertised as a ‘horror film’, a genre I stay clear of. That label, though, is misleading. Nefarious is subtle. It offers a study in motivation, an exploration of freedom (what does it take to be a responsible agent?), a critique of language subversion, and an engagement with the nature of evil. Sean Patrick Flanery delivers an exceptional performance as Edward Brady, a death-row prisoner apparently possessed by a demon. When the other main character, a well-meaning psychiatrist, dismisses this hypothesis as irrational, the demon retorts: ‘I am the most rational creature you will ever know.’ A thoughtful line that has equivalents in the writings of the Fathers. Kevin Turley reflects on the critical establishment’s booing of the film, which is what one would expect, for ‘to say Nefarious is countercultural is an understatement’: ‘It reminds anyone who will listen that there is only one battle — and that we are all enlisted in it, whether we realise that or not.’ We may prefer to close our eyes and pretend the battle isn’t real. This is not an easy movie to watch. It couldn’t be. But it is worth seeing.

Polyamory?

‘Surely one of the pleasures of monogamy’, writes Miranda France in a bracing review of three recent books about sexual liberation (?), ‘is knowing that your partner isn’t having amazing sex in a boutique hotel while you’re taking out the bins.’ I’d call that a definition of happiness by minimal criteria. Still, her frank emphasis on pleasure is rather a relief in the context of these putative accounts of desire in the twenty-first century, which seem to be marked by joylessness. The trend they chronicle isn’t catching on among the young: ‘More and more young people are opting for sexit. Where centuries of prohibition failed, society has finally found the way to dampen teenage appetite: sexual saturation.’ France’s reading, basically sympathetic, certainly not moralist, is thought-provoking. It shines a torchlight up what is evidently a cul-de-sac, indicating a cultural, social, anthropological and indeed theological task: that of rediscovering and showing what desire is for.

Trinity Sunday

‘It is customary on Trinity Sunday for bishops to issue a pastoral letter to be read in place of the homily. It is said that this is because bishops fear their priests will lapse into heresy if left to preach themselves. Many priests, true, have a dread of today’s feast, not because they do not believe that God is three-in-one, not because they do not love the trinitarian mystery, but because it is so hard to talk about it. This shouldn’t surprise us. God is by definition greater than anything we can think up or imagine. It is his nature to be transcendent. He reveals himself to us for love, but our minds are inadequate to grasp what is revealed. St Augustine, one of the acutest minds the Church has known, wrote at the end of his treatise on the Trinity: ‘Free me, Lord, from a multitude of words!’ Having written that immortal book, he looked back over it and thought: it would be better to say nothing than to speak so inadequately. We know how he felt. Yet we crave illumination. We wish to comprehend. We have to say something.’ From Entering the Twofold Mystery.

Distinctive Voices

The Bible, writes Marilynne Robinson, displays ‘an interest in the human that has no parallel in ancient literature’. Her Reading Genesis is so thrilling because she understands this interest and shares it. Take Rebekah, who ‘alone in Scripture laments the discomfort of her pregnancy’. Did she feel let down by life? ‘Did Abraham send his servant to find a wife for Isaac, and forbid him to take Isaac with him, because Isaac himself was unprepossessing? […] Would the bride have been pleased to be brought to Sarah’s tent, and to comfort Isaac for the death of his mother?’ The more Robinson engages with Rebekah, the more she brings out her ‘very distinctive voice’ marked by ‘expectations she cannot bear to have disappointed, though I speculate, they have been disappointed since she first saw Isaac walking in that field. Disappointment is a very familiar turn in human affairs, therefore always relevant to the larger question of divine providence at work in it.’

Not Simply Itself

Early this morning, having listened to the BBC World Service‘s updated account of anguished realities in Ukraine and Gaza, of the forthcoming election in Great Britain taking place ‘against a pretty sour backdrop’ with voters not liking ‘any of the politicians or any of the political parties’, being citizens of a country ‘that senses it is on the wrong track and that life is getting worse’, I found myself reading an essay by Alice Albinia about a recent book, The Rising Down. It chronicles ‘the human experience of land and describes with acuity how the places we know are often linked through our experiences, thoughts and memories to other lands.’ The book’s author, Alexandra Harris, describes this as ‘the very common, complicated, unpredictable habit humans have of making places from other places, so that nowhere is simply itself.’ When this is acknowledged, Albinia writes, even patches of territory will be found to ‘sing’. It seems to me that political rhetoric worldwide moves in the opposite direction; and that that accounts in part for serial political, cultural and religious deadlocks.

View of China

One discovery leads to another. I’m interested in the linguist Ross Perlin’s work. He writes: ‘At the current unprecedented rate of language shift, a significant portion of the world’s cultural and linguistic diversity will disappear over the next century.’ As codirector of the Endangered Language Alliance, he documents languages at risk and supports linguistic diversity. Reviewing his recent book Language City in the New York Times, Deirdre Mask praises it as ‘a gorgeous new narrative of New York’. She throws in this aside: ‘I invite you, too, to binge-watch Perlin’s fascinating YouTube dispatches from China.’ The invitation was irresistible. That is, I haven’t binged, but have watched one now and again. In a series of ten-minute features filmed by his fiancée some 15 years ago, edited by a couple of mates, Perlin takes us on a journey to visit synagogues in Shanghai, shamans in the uplands, old people walking pet birds before settling down to mah-jong, roadside cooks. He converses fluently with natives in Chinese dialects while presenting a humane, witty, philanthropic account for his viewers – in Yiddish. This series is a phenomenon, heart-warming and enlightening. Take a look at A New York Jew in China.

Maturity

Ina Weisse’s film The Audition wasn’t a box office success, as far as I know; perhaps it couldn’t have been. The story of an ambitious violin teacher pushing a student over the brink is too marginal to engage the mainstream. There are cinematographic imperfections – excessive longueurs. Yet it is a powerful film, credibly displaying a Cain-and-Abel rivalry and, at the same time, a delicate and difficult motif present in art since Antiquity: that of a mother devouring her children. It is wholesome, albeit unpleasant to be reminded that the pursuit of beauty – of perfection in beauty – can be terribly compromised; and of how imbalance in our own lives can make us make impossible demands of others. There’s an exchange that will remain with me. At one point Anna Bronsky, the teacher, hears a recording of herself playing the violin. At first she cannot recognise her own sound. Then she remarks to her husband (whom she cheats): ‘It’s rather immature.’ He replies: ‘That’s what’s beautiful about it.’ One realises: When ‘maturity’ comes to spell ‘iron control’ or even ‘loss of innocence’, it can be fatal.

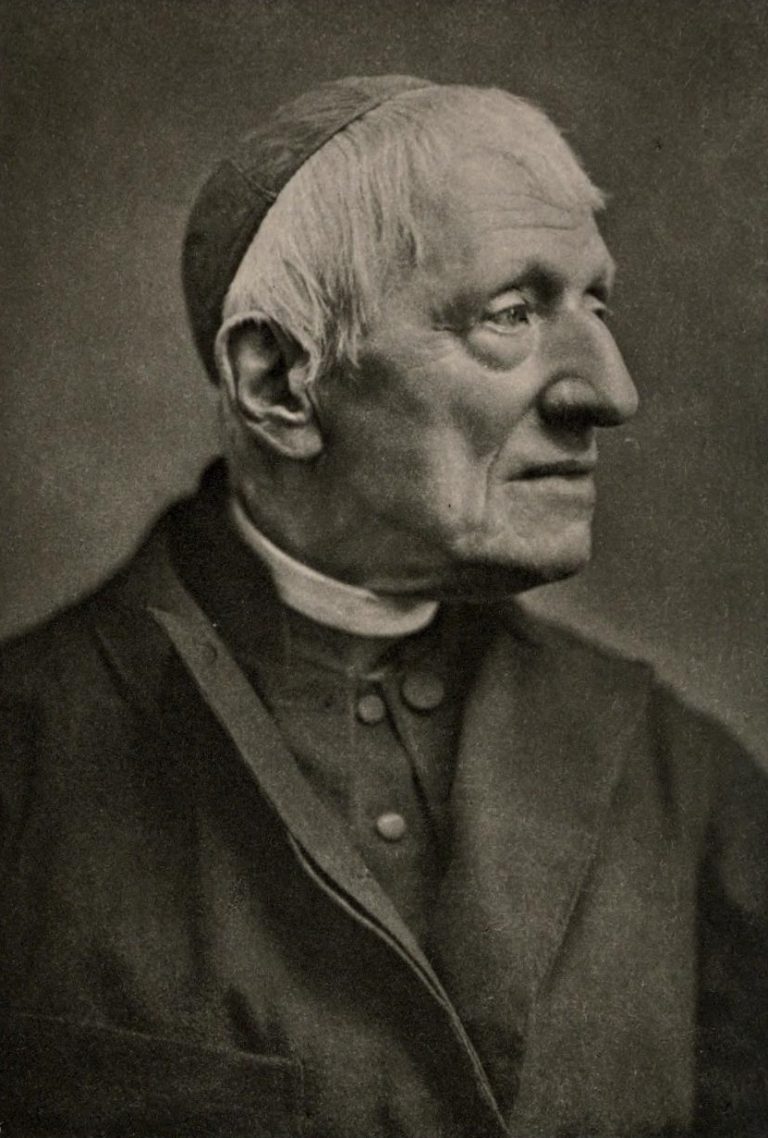

One Step

With elegance Daniel Capó draws an arc from the well-known line in Newman’s poem, ‘one step enough for me’, to the scene of an eleventh-century Iranian sheikh before a crowded audience in Tus, making the figure seem self-evident. What promise there is in a single step taken freely, benevolently towards another! It is a matter of caring and of accepting others’ care.

Capó notes: ‘We know we are fallible. We know no less that none of our faults — however grave they may seem — will define us forever. We are poor and weak, absolutely, but there is beauty concealed in this fragility of children. There is truth in it, too — in the image of a mother dandling her child on her knee; of a family tramping under the stars looking for a home. Love grants us this certainty. The one thing it asks in return is that we draw one step closer, from one heart to another, so to discover the substance and savour of humanity.’

Keeping Rubrics

I am reminded of a request one of my predecessors made to Rome a few years ago for a liturgical dispensation. It was not granted. Here is Gregory IX’s responsum to Archbishop Sigurd of Nidaros (medieval Trondheim) dated 8 July 1241:

‘Since we have learnt from your account that it sometimes happens in your country that children, for lack of water, are baptised in beer, we give you the following response: since according to evangelical doctrine it is needful to be born again of water and the Holy Spirit, those who are baptised in beer are not to be counted as rightly baptised [non debent reputari rite baptizati]’ (DH 829).

A marginal concern, but perhaps worthy of a footnote to Gestis verbisque?

Chastity Overseas

The last few months have seen many thoughtful responses to Chastity: Reconciliation of the Senses in the United States, where the book was published in January. I’d single out three. Nathanael Peters reviews the book in a contextual essay, stating a premise with which I am in full agreement, ‘I’ve come to see chastity as primarily a question of freedom’. He goes on to provide an illuminating juxtaposition with Maestro. Carl E. Olson is attentive to ‘a robust and self-aware anthropology’ and, a really important point, to the eschatological dimension of chastity. Jared Staudt engagingly writes of ‘the resurrection of chastity’ – and indeed there is much to suggest that it is not dead but, like Jairus’s daughter, ‘sleepeth’. He notes: ‘My largest takeaway from the book regards the way in which chastity fulfills our nature rather than diminish it’, and this delights me. It is a blessing for a writer to have careful readers. The book, already out in Spanish, is currently being translated into Italian, French, Portuguese, Swedish, Norwegian, and Greek.

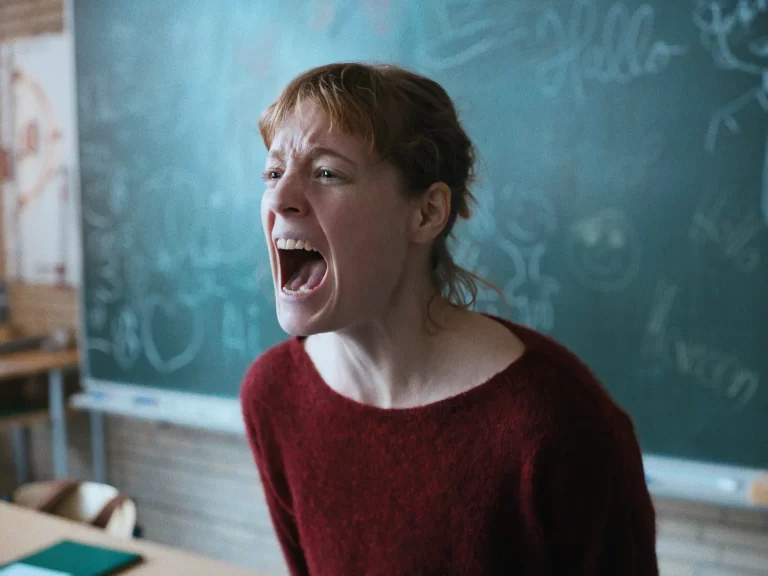

What Is Truth?

A spate of reviews convinced me I should go and see Ilker Çatak’s The Teachers’ Lounge, which premiered in Norway yesterday. I am glad I did, though I can’t say it was a fun night out at the cinema. The film is painful to watch as it places its finger deftly in one societal wound after another. It touches issues of racial prejudice, surveillance culture, subverting rhetoric, and the backfiring of good intentions. At one level it can be seen as a critique of liberalism gone dictatorial, driven by a mixture of self-righteousness and a furious desire to please. But there is more. Mathematics are a motif, pointing towards the question of what constitutes an objective burden of proof. Can truth ultimately be proven? This question suffuses the whole. I was unprepared for the burlesque of the ending, set to a rousing interpretation of the overture to Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Puck’s final monologue in the play might provide one interpretative paradigm. The Biblically minded might find another in Leviticus 19.14.

Bonum facere

The German Bonifatiuswerk has done a tremendous amount to assist the rebirth of Norwegian Catholicism, enabling strong bonds of assistance and friendship.

To celebrate the foundation’s 175th anniversary, EWTN Norway has made a small video to chronicle the activities of the Bonifatiuswerk in the prelature of Trondheim.

You can watch the video here.

Athanasius

From The Shattering of Loneliness: ‘Athanasius does not maintain that all sensual impulses lead to God. There is a distinction to be drawn between our heavenly, ‘logical’ longing and our earthbound, ‘illogical’ desire. Yet the fundamental principle holds: any authentic longing, any longing that, even implicitly, points towards eternity, is a possible path towards God. Dying, Christ declared a sentence of death on death. Death alone is dead. In Christ, we go beyond what is ‘natural’ so that our nature, one with the Word, is no longer what it used to be. The condition of newness, which corresponds to what at first we were, makes of us, too, possible epiphanies. ‘Our arguments’, says Athanasius, ‘are not composed merely of words, but have the proof of their truth in experience itself.’ On this basis he concludes by professing the principal result of the Word’s incarnation: ‘He became human that we might become divine.’’

The Church celebrates the feast of St Athanasius today, 2 May.

Akhmatova

From the Notebook of Anna Kamienska:

Akhmatova. A thick volume of her collected poems, as if they were written by one person. But after all there were so many — from youth to old age. The elegant, refined lady and the old peasant who roars in pain and beats her forehead against the church floor: “Lord!” The poet thronged by crowds of admirers and snobs, and the old woman: wise, comprehending, like the earth, like a peasant rocking her dead child in her arms. […]

Music teaches us the passing of time. It teaches the value of a moment by giving that moment value. And it passes. It’s not afraid to go. […]

The dangerous passion for absolute purity. To evaporate with the atom. Wake up!

Poor Fit

In 1959, in Erasmus and the Humanist Experiment, Louis Bouyer wrote: ‘Many, indeed, consider that the Christians of the sixteenth century were unaware of what was required to christianise the immense fund of experiences and new realities that characterised their epoch, and that was why the new world broke from a Church whose representatives were incapable of emancipating themselves from their own set ways. This explanation is at once convenient and flattering for Christians today. It should cause no astonishment that many of them consider it all but axiomatic. They contend, in effect, that, were the modern world to pay them proper attention, their intelligent sympathy would quickly conquer it, and that this world remains alienated from the Church solely through the failure of its retrograde elements. Convincing though this thesis may at first sound, it is certain that such simplification fits in poorly with objective history.’

Blake

One is so accustomed to everything carrying a price-tag these days that it seems surreal to be offered something rich, instructive, and beautiful for free. But that is what happens if you go to the Fitzwilliam Museum to see William Blake’s Universe, on until 19 May. It is a fascinating show. I appreciated its endeavour of contextualisation, which goes beyond the obvious statement that Blake was a Romantic in a Romantic age. It stresses the conviction of several disconnected intellectuals around 1800 that Europe had gone spiritually bankrupt, that a new foundation must be laid. The very fact of such a collective conviction’s arising provides food for thought now. Apart from that, I largely agree with Jonathan Jones’s well-written critique, though I admit I am less enchanted than he is. Jones notes: ‘The point of Blake is the ebullient and unique totality of his vision, which you have to dive into and embrace.’ The totalitarianism of Blake has a suffocating aspect that this exhibition evidences, also in its juxtapositions. A morning’s dip was sufficient for me. Afterwards I was content to emerge into a sea of concrete daffodils.

Living Vastly

Today’s collect begins with a tripartite confession. It formally lists names of God. At the same time it defines the human condition: ‘Deus, vita fidelium, gloria humilium, beatitudo iustorum’. On this account, true life unfolds in response to fidelity and trust; glory, the conforming of our being to divine nature, is a function of illusionless self-knowledge, known in tradition as humility; beatitude, the durable perfection of happiness, correlates to just reasoning and action. We are recalled to a fundamental tension of the Christian condition: sublime aspiration presupposes realism and calls out for implementation in positive action. There are no short cuts in learning to sustain this tension. It calls for perseverance, creativity, and courage. It enacts a broadening of perception and of sensibility. To be a Christian is to learn to live vastly, to be drawn towards a horizon that forever broadens, though its coordinates correspond precisely to the intimate motions of our heart of hearts.

More Alive

With characteristic accents, Elizabeth Anscombe shares her remembrance of Ludwig Wittgenstein:

‘He had an extraordinary understanding of why people thought the things that they did think in philosophical argument, so that, when he undermined it, his undermining showed that he was getting at the nerve, the root: it was not a superficial refutation.

He also struck one as a great deal more alive than almost anybody else.

He also had an amazingly good judgement of what it was it was sensible to tell somebody to read, what was right for them.’

It is a wonderful tribute.

Learning to Pray

Before Mass this evening, I read this passage in Father Irénée Hausherr‘s Prière de vie, vie de prière, surely one of the most helpful books ever written:

‘There is talk of the “particular friendships” that are an obstacle to prayer. They are indeed. But it is above all “particular enmities” that render prayer impossible. Do not, then, do anything at all that would hinder you from giving yourself up, immediately afterwards, to peaceful silent prayer. For this to happen, “may God walk alongside you” [as Evagrius wrote]. That is to say: may no enterprise of yours be realised without prayer. The true path to contemplative prayer is life itself. It would be an illusion to dream of union with God by some means other than that practice which leads to contemplation.’

Undset in the East

Selma Ancira, distinguished translator of Russian literature into Spanish, shares an insight from ‘the book by Marina Tsvetaeva I’m in the middle of translating’. The great poet wrote to a friend:

‘And Sigrid Undset, have you read her? Kristin Lavransdatter. It’s a wonderful book. A Norwegian epic. The best thing that’s been written about the fate of woman. Faced with it Anna Karenina is a mere episode.’