Words on the Word

17. Sunday C

Genesis 18:20-32: Will the judge of the whole earth not administer justice?

Colossians 2:12-14: God has brought you too life with Christ.

Luke 11:1-13: Lord, teach us to pray.

The reading we have heard from Genesis, about the intercession of Abraham, belongs in a context. Permit me to remind you of it. Abram was called away from his homeland Haran, in what is now Iraq, at the age of 75. He was told to walk towards a land unknown to him, which God would give him as an inheritance. The Lord said: ‘I will make you into a great people. I will bless you and magnify your name.’ Abram set off with Sarai, his wife, and a large retinue.

The plan seemed obvious: God’s providence would give him a new homeland; his wife would bear him a host of children. It didn’t turn out that way. Abram was given to see the land by way of a promise, but was repeatedly driven out of it. When we meet him in today’s text, he still has no property to his name. He lives on others’ grace. He still has no legitimate heir. A quarter-century has passed. He is 100 years old. We can understand that he may have asked himself: Was the voice he had perceived as God’s call in fact delusion and wishful thinking?

The sense of being exposed to unfulfilled promises can embitter people’s lives. We may have have experienced it ourselves. When we’re not given what we think is promised to us, out tendency is to circle round ourselves and our disappointment. We keep reminding ourselves and others of what could have been but didn’t come about; of what we had deserved but were not given. A disappointed man or woman is easily imprisoned in an egocentric bubble. He or she forgets that other people exist and likewise have dreams, hopes, and needs. There’s a risk that bitterness turns into a chronic condition.

In Abraham’s case, the opposite happens. The longer he has to wait, the more spontaneous and energetic is his empathy for the world around him. When Abraham finds himself standing before Sodom, it is because he had been led there by three mystic persons — the Fathers saw them as a prophetic sign of the Blessed Trinity. The three had announced that the time of waiting was past: a son would be borne to him within a year. Sarah met their announcement with cynical laughter, which we can quite understand, naturally speaking. Abraham, in contrast, was open to the ostensibly impossible, quick in his response. The uncertainty he had lived with for so long had not hardened his heart. On the contrary, his heart had become soft, tender, and vulnerable, like God’s heart. The same disposition finds expression when he hears the Lord’s judgement upon Sodom and Gomorrah on account of their grievous sin.

Abraham knew what Sodom stood for. Already when he and Lot had returned to the land from exile in Egypt, it was clear that ‘the men of Sodom were evil and sinned terribly against God’ (Genesis 13:13). He had no illusions; he did not relativise the Sodomites’ sin. Still he could not endure the thought of their destruction. After all, there could be a single righteous man among them, a single subject with the will to follow grace! Surely a righteous God could not condemn them all en masse? ‘Do not think of it!’ exclaims Abraham. Only one who has put on the mind of God can pray thus.

When the disciples in the Gospel ask Christ, ‘Teach us to pray’, Abraham offers them a perfect exemplar. Abraham, for being a very old man, is a child of God. Therefore he spontaneously looks upon God as his Father. God’s holy name is glorified in him — he resembles an embodied tabernacle bearing God’s presence. Through Abraham God’s kingdom gains a foothold in the world. Even after waiting long for God’s word to be fulfilled, he knows he will receive what he truly needs, his daily bread. As a matter of course he confesses his nothingness and sin, praying insistently for the pardon of others’ sin. He looks away from himself and is therefore outside the tempter’s remit. His is not a prisoner of anything in this world. He is a free man.

The example of Abraham reminds us that prayer is not primarily something we do. It is the essential expression of something we are. What Paul asks of us when he exhorts us, ‘Pray without ceasing’ (1 These 5:17) is to let ourselves be transformed by God’s power in Christ Jesus.

If Christ is alive in us, our very respiration becomes a prayer to God, an expression of trust, thanksgiving and intercession, for our heart will long to see God’s mercy spread itself over all people, including the most hard-nosed sinners. To learn to pray in this way, patience is called for. Abraham wandered about for 25 years while the word of God gradually penetrated his consciousness. The parables of Jesus summon us to great perseverance. They tell us to carry on faithfully and not to give up. They assure us that we must affirm, even when engulfed in spiritual darkness, our conviction that God is good, that he loves us and wills what is best for us. That certainty is to become the foundation of our existence and of our relationships with other people.

It may seem that what is demanded of us is superhuman. Well, it is. But we are more than our nature. We are called to live supernaturally. ‘You who were dead have been brought to life with Christ’, says Paul. We also, brothers and sisters, have received a share in this new life. Let us then live it, live it in such a way that it shows, in order that God’s power through our weakness may accomplish its work of healing in our sick world. Amen.

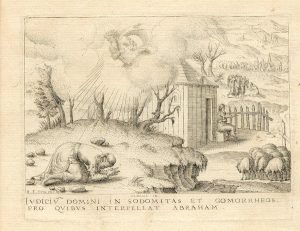

Etienne Delaune, Abraham ber Gud om å spare Sodoma og Gomorra.

Strasbourg: Cabinet des estampes et des dessins.