Words on the Word

22. Sunday C

Sirach 3.17-20, 28-29: There is no cure for the proud man’s malady.

Hebrews 12.18-19, 22-24: You have come to God himself.

Luke 14.1, 7-14: When someone invites you to a wedding feast.

On the face of it, today’s readings are all about humility. The first tells us: ‘Behave humbly’. The second exhorts us to own our littleness before God’s majesty. The Gospel proclaims: ‘Whoever humbles himself will be exalted’. We need such reminders, but they may leave us cold, for it is hard to conceive of humility as a positive virtue. It seems to lack contours. It stands for the absence of pride, OK. But what might be a desirable image of humility? How might we think of it, not just in terms of shedding the bad, but of acquiring the good?

As it happens, the answer is given in the texts we have heard. If we dig a bit deeper, we find a second theme interwoven with the leitmotif of humility. It is the theme of hospitality. To be humble is tied up with knowing how to receive guests, and with knowing how to be a guest.

Christ, in the Gospel, tells two stories to bring this point home. The first is about being invited to a wedding. Let’s note this: to receive an invitation at all is an honour. We have all had the experience of drawing up guest lists for special occasions. We know the constraints imposed by space, catering, expense. We can’t invite everyone we would have liked to be present. To be on the list is to be favoured. Such favour requires a gracious response. To organise a wedding is a complex operation. It involves the encounter of two families, two sets of friends, two different lives henceforth welded into one.

As a guest I must enter into my hosts’ choreography. I must give myself over to it fully, resolved to give my best; then to receive, and be gratefully surprised by, what others have to give. If, instead, I turn up as if I were a paying customer, claiming a special seat or companion (preferring the known to the unknown); if I think the feast is about me, about confirming me in my sense of status. I’ll have lost the plot. I’ll be something much worse than a mere party-pooper: I’ll have reduced an occasion of grace to one of consumption. Called to have a share in the construction of joy, I’ll instead have brought sadness. Usurping a place that was someone else’s, I’ll have missed the place that was uniquely mine. I shan’t be where the bridegroom looks for me. I’ll have forfeited his mark of generous friendship.

This story, then, is about being able to receive; about abandoning calculation; about nurturing the trust that the place assigned to me by a host who desires my presence is the right, the most blessed, and thus, in fact, the most honourable place. The other story Jesus tells is also a summons to ditch transactional thinking. When it’s your turn to be host, he tells us, don’t invite people of means in order to obtain a distinguished invitation in return; don’t let social ambition come between you and the pleasure of having guests for their own sake. Savour the blessedness of giving, of enjoying others’ joy, which will be all the greater for being unexpected, undeserved, entirely gracious.

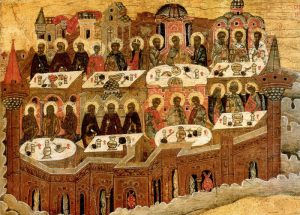

That’s how God gives, you see. He would have us learn to be like him, that, one day, we may be at ease around his table. For the backdrop, naturally, is the marriage of the Lamb on Holy Zion, where angels are gathered in festal throng. Of that celebration each Eucharist is a sacrament. Each Mass is a trial run of the heavenly banquet. And when we look at ourselves in truth, who could say (s)he merits to be here, to be called by Christ to move up higher, to the point of receiving from his hand, through the hand of a priest who, for being unworthy, is ordained to represent him, the Bread of life, the Cup of salvation? The poor, the maimed, the blind: that’s you and me. Thank God our Host has a soft spot for the likes of us!

To enter into this logic of hospitality is to learn to be humble. Seen in this light, humility is both attractive and delightful. To keep this insight alive is vital in a world that increasingly sacrifices truth to illusion, practising ever more ghastly, systematic selections of candidates for any guest list, assuming the divine Host’s prerogatives.

Does this sound a bit cryptic? I may best illustrate what I mean if I share a personal memory.

Some years ago, I had the privilege of singing in a production of Handel’s Messiah. An alto in the choir had a son with Down’s, called Felix. Felix came to every rehearsal. Standing behind the conductor, he co-conducted vigorously. When the music was sad, he wept. When it was joyful, he was radiant. After the performance, he gave a noble speech to the choir, whom he addressed as his friends. I dare say each of us thereby felt ennobled.

I got to know Felix only slightly. Still I can say: he impressed me, taught me important lessons. The thought of Felix (whose name means ‘happy’) gives me joy. There are countries now, in the Western world, that no longer register any births of children with Down’s. This is presented as scientific progress. The Felixes of this world are unwanted, deemed encumbrances. Euthanasia, likewise, is spreading from country to country, advertised as a human right. Yet wherever euthanasia is available as choice, involuntary euthanasia is soon being practised. Underneath a surface of what can seem like impenetrable bureaucratic discourse, an existential combat is taking place.

Faced with such sinister developments, we have work to do. The pursuit of humility is not just a matter of devotion; it is about upholding the dignity of all human life, recognising ourselves among the weak and outcast, standing up for table fellowship. To be humble on these terms is not to be meek and mild; it requires courage, strength, and perseverance in the face of hostile opposition. We are to rise to this summons, strengthened by the food of immortality. May we not be found unworthy of Christ’s example and sacrifice.