Words on the Word

8. Sunday C

Ecclesiasticus 27:4-7: In a shaken sieve, the rubbish is left.

1. Corinthians 15:54-58: The sting of death is sin.

Luke 6:39-45: Why do you observe the splinter in your brothers eye?

There is a connection between the imagery of our first reading and that of the Gospel. It is made up by the notion of ‘rubbish’. From Sirach we heard that ‘In a shaken sieve, the rubbish is left’. In the Gospel the Lord asks, ‘Why do you observe the splinter in your brother’s eye?’ The word ‘splinter’ is specific. The Greek noun it translates is general. The dictionary defines it as ‘chaff, a chip of wood, bits of wool, such as birds make nests of’ — in other words, a fragment of rubbish. In the second act of Peer Gynt, when the protagonist encounters the Mountain King’s daughter, she explains that things on the whole are not, the ways trolls see them, the way they appear. Should Peer come with her to her father’s splendid castle, she explains, it might seem to him little but a ‘rude quarry’. Peer answers her forthwith:

It’s just the same with us!

The gold will seem to you rubbish and waste:

Perhaps you’ll even think that the sparkling widow panes

Are nothing but old stockings and rags.

Of course, that is what they are, if we don’t happen to have trollish eyes! But to recognise rubbish for what it is, is not such an easy task. We easily lose our sense of what is genuine, what isn’t. It’s not so hard to discern the distinction in others. As for ourselves, we rather tend to expose our rubbish in gold frames. Those ‘old stockings and rags’ seem to us a transparent, trustworthy window on the world.

Most of us are inclined to relate to the world as we imagine it to be. A beamed-up eye is to our advantage. We do not want to see what surrounds us. We prefer to gaze within, then imagine the reality out there on our terms. We can live like that, fairly undisturbed, for quite a while. But the real will at some point make its claims felt, if not before, then at the hour of our death. We risk being unprepared. What does glorified rubbish amount to face to face with the Real?

Jesus Ben Sirach’s remark about rubbish is part of an exposition on speech. His image is a telling one. Anyone who has ever baked will conjure up before his or her inner eye the vision of chaff remaining in a sieve. Out into the compost with it! In the same way, says Sirach, the defects of a man appear in his talk. What can he mean? The sieve is an image of human intercourse. In conversation, we do what we can to distribute pure flour: that’s how we would like to appear. The rubbishy chaff, however, remains. It is harder to get rid of than ordinary kitchen rubbish. The risk is that it just accumulates and so, ever more, weighs down and conditions our inner life. We end up with a great load of rubbish inside. And that whereof the heart is filled, will flow out of our mouth, at some point or other. It is a paradox of life that we in fact very often project outwards what we would most dearly like to keep concealed. ‘The test of a man is in his conversation’, whether we like it or not.

We’re facing the challenge of mental and spiritual hygiene. We must learn to empty our rubbish deposits regularly. The sacrament of reconciliation is a splendid way of going about it. When I make a sincere confession, I own the truth about myself. I renounce all attempts to pretend that a ‘rude quarry’ is a royal castle; I call the rubbish by name. When it is thus named within the framework of the sacrament, it is blown away by the ever-fresh breeze of absolution. I am left blessedly empty, clean, and open, ready to see the world as it is, and myself as I am, without illusions, laved by grace.

To let rubbish be blown away in this way, is to participate in Life’s victory over death, as we hear in our second reading. This gigantic battle is most often enacted in humdrum circumstances. A splinter, a fragment of rubbish, can seem like nothing. However, fragments pile up. Piled-up rubbish is heavy to carry. Such a load lets us sense what Paul describes as the ‘power’ of sin. It can end up constraining us to walk bent-over.

I speak metaphorically, but there is, here, also a literal truth. Sin can, in fact, settle in the body and express itself somatically. A splinter in a vital organ, be it the eye or the heart, will naturally provoke an infection. Let’s remember the connection the Lord is keen to make between health restored and freely received pardon. Thank God, each one of us can get rid of the rubbish we carry, even when the splinters in our eye have formed such a compact mass that they are to all intents and purposes a beam.

Do make use of, then, the Church’s sacraments! Receive the Lord’s healing gift in order to find new strength and joy for life. Don’t let the sting of death remain. Pluck it out.

We must all begin with ourselves. ‘Can one blind man guide another?’ It is unlikely to end well. To recognise my blind spots is a good in itself. We must tirelessly make ours the prayer of Bartimaeus: ‘Rabbuni! Let sight be restored to me!’, then be ready to rise and follow when the Lord calls. By expelling, ever again, darkness from my heart’s store, the light will shine there. It will also, without my realising it, spread around me. The human being is a whole. If illumined by the light of Jesus, it becomes light and walks about like a living, consoling proof of God’s existence.

God’s purpose, let’s remember, is to transfigure the world. We are all called to carry the fire he cast upon earth by becoming one of us, bestowing on our nature, by grace, the possibility of sanctification, of divinisation.

In the Sayings of the Desert Fathers, we read of the encounter of two venerable monks. Abba Lot asked Abba Joseph what the purpose is of ascesis, that is, of the daily battle to clear out darkening rubbish and to opt to receive the Lord’s light. The old man stood up ‘stretched his hand out to heaven, and his fingers became like ten burning torches. Then he said: If you want to, you can become fire entirely’ (XII.8).

We can all become fire, quite simply because it is the Lord’s will to share his glory with us. May Christ’s living flame, then, burn up whatever rubbish remains in us and make us ready to enter, enlightened and made light, into our Master’s joy.

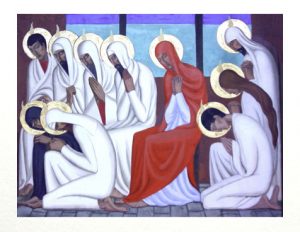

Abba Joseph’s claim, which can seem to us extravagant, is simply a confession of faith that what happened at Pentecost keeps happening in the Church, that the Spirit remains transformatively at work if we let Him. Mural by Dame Werburg Welch of Stanbrook Abbey.