Words on the Word

Good Friday

Isaiah 52:13-53:12: Ours were the sufferings he bore.

Hebrews 4:14-16, 5:7-9: Jesus, the Son of God, has gone through to the highest heaven.

John 18:1-19:42: There they crucified him.

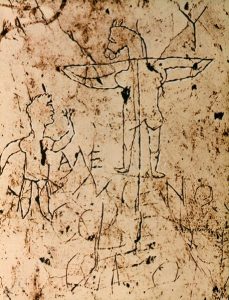

The earliest image of Christ’s crucifixion known to us is a graffito from the Palatine Hill in Rome. It is not exactly datable, but seems to originate in the early second century, when there were still Christians in Rome who had heard Peter preach. The drawing shows a human body with a donkey’s head, nailed to a cross. To the left of the cross is a man dressed like a soldier whose right hand is raised in a salute. A caption draw in clumsy, childish letters, and in approximate Greek, mocks him: ‘Alexamenos worships god.’ The drawing is a caricature. Its purpose is to ridicule Alexamenos. We can easily imagine the context. The inscription was found in a building that was once the emperor’s residence and a garrison for his troops. Among Caesar’s soldiers there will have been one who put his trust in the cross of Jesus. He would have seemed to his fellows perfectly absurd. The joke works to this day: ‘Does Alexamenos really worship a crucified man? You can’t be serious! What an ass!’

Following John’s careful account, we have accompanied Jesus step by step on his way to be crucified. We have seen the Son of God slapped, humiliated, paraded as a clown. We have heard him say, ‘I have come into the world to bear witness to the truth’ only to be met with the exclamation: ‘Crucify! Crucify!’ Pilate was minded to let the case drop. The will of the crowd was done nonetheless, a reminder that majority decisions are not necessarily just; that we, when we’re absorbed by an anonymous assembly, are exposed to mass enthusiasms that can turn into hysteria with a purely destructive goal.

Following John’s careful account, we have accompanied Jesus step by step on his way to be crucified. We have seen the Son of God slapped, humiliated, paraded as a clown. We have heard him say, ‘I have come into the world to bear witness to the truth’ only to be met with the exclamation: ‘Crucify! Crucify!’ Pilate was minded to let the case drop. The will of the crowd was done nonetheless, a reminder that majority decisions are not necessarily just; that we, when we’re absorbed by an anonymous assembly, are exposed to mass enthusiasms that can turn into hysteria with a purely destructive goal.

Crucifixion was the most demeaning form of execution at the empire’s disposal. It was used by way of advertisement and warning, reserved for criminals without citizenship. Many of us will have seen Stanley Kubricks blockbuster movie from 1960, Spartacus. When the rebellion which Spartacus had captained was put down in the year 71 BC, some 6000 slaves were crucified along the Via Appia leading into Rome. The nearest we get, perhaps, to imagining the symbolic charge of crucifixion at that time is the thought of the burning crosses erected by Klan men in the Southern States, still in the decade that followed World War II. Today we contemplate our Saviour crucified. We must not avert our gaze from the terrifying realism of the scene.

Neither must we think that realism is all. We must learn to look upon the cross with faith. In that respect the Church, our Mother, shows herself today a splendid pedagogue. Having reminded us that the suffering of God’s Anointed was predicted in Scripture, as in the passage read to us from Isaiah; having let us hear the Letter to the Hebrews say that Jesus, on the cross, offered himself as High Priest; having led us, in Christ’s footsteps, to Calvary, there to see blood and water flow freely from his side, sealing the new and everlasting covenant — the Church give us, now, a moment’s respite to find our bearings, to take in the full extent of what has gone on. The Lord’s sacrifice is accomplished. His body hangs lifeless, heavily on the tree of shame.

Then, we are led onwards. In a moment I will invite you to join me in the universal intercessions. In solemn cadences we pray with an outreach that spreads gradually, like the circles on the water of a calm forest lake into which you have cast a pebble. When Israel had left Egypt and reached Marah, the water there was bitter. The people cried out to the Lord. The Lord showed Moses a tree. Moses threw it into the water, ‘and it became sweet’ (Exodus 15:25). Today the cross is cast into the chaos-waters of our world, and behold: the water is calmed and filled with blessing.

With the whole Church we pray for ourselves, for our Holy Father, for the Church’s ministers, and for the catechumens; then for other Christians, for the people of the First Covenant, and for those who do not believe in Christ; finally for secular leaders and for all in need. There is no one, today, who is excluded from the range of intercession. Thus we ascertain that the water from Jesus’s side has cleansed and renewed the world, the way the Flood did in Noah’s days. By taking upon himself our sin, God has cancelled it. No impurity remains outside the reach of the flow of his salvation, provided we ourselves do not build locks.

After the intercessions, something wonderful happens. The cross, which a while ago represented utter shame, is carried in in triumph as we sing: ‘By the wood of the cross, joy entered the whole world.’ A transformation takes place; we see the cross at one and the same time as something in itself evil and as the sign of God’s vanquishing evil. The Crucified, we sing, is not just ‘Jesus of Nazareth’, as Pilate wrote. He is our ‘holy God, holy and strong, holy and immortal.’ He let himself be brought low to raise us up; by his wounds we are healed.

While we proceed to worship the cross, or rather, to worship him who, on the cross, redeemed us, the choir sings some very daring words: Dulce lignum, dulce clavo, dulce pondus sustinens. In English: ‘Sweet is the tree, sweet the nail, which carried so sweet a load!’ What was bitter has become sweet. Death has revealed itself a source of life. Thus the cross stands before us, not only as a mark of victory, but as something loveable and dear.

In the cross of Jesus we find the strength we need to behold the world, and our own lives, lucidly, yet with deep and fully realistic hope. The task entrusted to us is to carry this cruciform hope into our lives as a torch, holding it high. It may cause us to be mocked like Alexamenos of yore; that shouldn’t bother us. We know, by Scripture’s testimony, the teaching of the Church, and our experience that the cross is the key to the enigma of both life and death. We honour it with reverence and say, ‘Hail, Cross, our only hope’ — Ave Crux, spes unica. Amen.