Words on the Word

Good Friday

Isaiah 52:13-53:12: See, my servant will rise to great heights.

Hebrews 4:14-16; 5:7-9: Let us be confident that we shall have mercy from him.

John 18:1-19:42: Pilate wrote out a notice and had it fixed to the Cross.

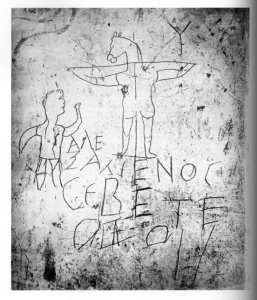

The earliest representation of the crucifixion known to us is an inscription carved in plaster near the Palatine Hill in Rome. Its precise date is uncertain, but it may have been made as early as the early second century, when there were Christians about in the City who had heard the Gospel preached by Peter and Paul. The inscription portrays a crucified human body with a donkey’s head. In a corner, there is what seems like a Y-shaped tau cross, so dear to Francis of Assisi. To the left stands a man dressed like a solider with one hand raised in homage. A caption announces in barely literate Greek: ‘Alexamenos worships god.’ The graffito is a caricature. It intends to ridicule the worshipper. The joke is timeless. ‘Does he worship a crucified man? You can’t be serious. What an ass!’

It is sometimes said that, to appreciate the symbolic charge of a crucifix in antiquity, we moderns should think of a hangman’s noose or an electric chair. I think this insufficient. The gallows and chair were thought up as humane means of execution. The cross, meanwhile, was designed to cause a maximum of drawn-out anguish. Also, death by crucifixion is messy and humiliating. Alexamenos is presented, in the drawing, not just as a fool, but as an indecent man.

Today you and I stand by Alexamenos’s side. We bow low before the Cross. We are not blind to the disgrace it represents; but we see through it. We glimpse a larger truth. ‘No one has greater love than he who lays down his life for his friends’ (John 15.13). The Cross is the emblem of such love. We are the friends.

In the Passion, we hear people cry, ‘Crucify him!’ They want to get rid of him. They’ve had their fill. It was pleasant enough to hear him for a while. He said very pretty things; he had charisma. Yet he required such investment without any promise of tangible gain. ‘Give us instead Barabbas!’ — the revolutionary with a strategic plan, a vision for a restructured society with greater individual freedom, lower taxes, pledges that make sense! This other fellow, — David’s son, God’s son, what does it matter — just make him go away, reduce him to silence at last.

Silently he suffered, endured, and died. Silently we contemplate him now. But this silence is not a mute silence. It speaks, it cries out! It bears the message of a love that has conquered the world and overcome death. This love is unstoppable. It is definitive, manifestly absolute. For yes, indeed: here on this Cross we worship God. Even face to face with his humiliation we hold our head high. What today seems like the end is the beginning of everything. Sheol trembles. Death unravels. In the East, we recognise the gentle shimmer of dawn.

By the Lord’s death, by his accomplished sacrifice, deathless hope is given us. A hope that carries.