Mellifluity

‘The Doctor Mellifluus‘, wrote Pius XII of St Bernard, ‘was remarkable for such qualities of nature and of mind, and so enriched by God with heavenly gifts, that in the changing and often stormy times in which he lived, he seemed to dominate by his holiness, wisdom, and most prudent counsel.’ He was also an exceptional communicator, as his epithet suggests. In a marvellous text read at Vigils today, Bernard anticipates interactive media. He has all of humanity hanging on the Blessed Virgin’s lips as she ponders her response to the Angel Gabriel’s Annunciation. ‘Answer quickly’, he urges her: ‘this is no time for virginal simplicity to forget prudence!‘ There is rhetorical delight in this passage; there is also great seriousness. Bernard reminds us that Christmas concerns each one of us. The Virgin’s ‘Yes’ is the source of our hope. We are called to make it our own.

Systemic Change

Let’s start with an easy question: What is the Incarnation?

— Well, I’m not sure it is such an easy one. First of all, it is an impossible paradox, because it is the account of the union of two incommensurate entities: the uncreated being of God and our being of dust. The great Christian wonder is before that mysterious union. […] We need to remember that in becoming flesh, the Word didn’t simply occupy one human body as a guest for 33 years. Human nature as such — that is, flesh — was invested with a potential for divinity. And so being a human being in the wake of the Incarnation isn’t the same as being a human being before the Incarnation, whether or not one believes in Christ and whether one even knows that Christ ever walked on this Earth. We like to talk about things being ‘systemic’ these days, and something systemic happened to human flesh through the Incarnation that opened it to transcendence and to eternity.

Perspective

As a young Cartusian, Dom Jean-Baptiste Porion wrote to his sister: ‘I ascertain the riches contained in a single perspective, the outline of a mountain, say, with its pine trees in the golden glory of May, in the mists of October, or whenever. We must become the mirror of this beauty and its echo. It always reveals something new, yet every time it says it all. I wonder whether travel is worth the bother.’ In a quite different cultural environment, Zhu Xiao-Mei has written of her teacher Gabriel Chodos that he taught her this: ‘In order to really learn to play the piano, to really learn music, it is as well to penetrate to the depth of a single piece as to study many different pieces. Many great researchers know this: it is by scrutinising over time a specific, circumscribed subject that one makes the most important discoveries and thereby develops a method that will allow one to work on any subject.’ How desirable to have this degree of patience, perseverance, and contemplative flair.

Rorate

The liturgy of Advent is like a camera lens shifting from panorama to focus on minuscule detail. We set out from cosmic longing as we call on heaven and earth, the dew and the fruitful earth to bring forth the Saviour. Then our expectation is anchored in history unfolding linearly from creation to the call of Abraham; from the story of Israel to the Forerunner; from Mary’s Yes to the Child in the manager. Our faith is beautiful. But it is not reducible to poetic imagery. It is based on things that happened; and points towards things that will happen. Our Lord Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God, is the presence towards which all earthly light points. He himself is a source of uncreated Light shining so that the world might find salvation, hope, and joy. In our Rorate Mass a reflection of this Light embraces us comfortingly. When the Church through the liturgy lets us hear the Prophet’s words, ‘I will save you’, it is not by way of a generic statement. It illumines each one of us. Let us then become light.

Transition

Whoever wishes to live in Christ, wrote St John of the Cross, must dig deep, for Christ is ‘like a rich mine with many pockets containing treasures: however deep we dig we will never find their end or their limit. Indeed, in every pocket new seams of fresh riches are discovered on all sides. […] The soul cannot enter into these treasures, nor attain them, unless it first crosses into and enters the thicket of suffering, enduring interior and exterior labours.’ There’s no masochistic glorification of pain in this statement, simply the expression of an incontrovertible fact: the transition from our created nature wounded by sin to the uncreated, holy Light of God is so immense, so categorical that it will be painful. We must let go of much. To perform this transition, said St John, can feel like traversing a dark night. There we become acquainted with Christ’s Cross, which symbolically effects the intersection of our life’s horizontal and vertical axes. ‘The cross is the gate that gives entry into these riches of his wisdom; because it is a narrow gate, many seek the joys that can be gained through it, but few desire to pass through it.’ Do I? (Cant.Esp. B, str. 36-37)

Fear Proved Wrong

‘On the night I was born’, says the indomitable Heidi Crowter, ‘my mum cried to my dad, saying “She will never get married or be a bridesmaid” — which’, she adds, ‘I proved wrong.’ The fears an expectant mother can feel on learning, like Heidi’s, that her child has Down’s are legion and readily understandable. What is terrible is that our society largely just confirms them, to the point of making such a mother feel it would be cruel to give life to such a child. An alternative account is needed, like the one presented a few years ago in this luminous video. It declares with great authority: ‘Your Child can be happy!’ The film was produced for World Down Syndrome Day, 21 March, which happens to be, too, the feast of St Benedict. His great question was and remains, ‘Who is the man that wishes for life?’ (RB Prologue). We might add: Which is the world that does? Jérôme Lejeune, discoverer of Trisomy 21, wrote, ‘The quality of a civilisation is gauged from the respect it shows its weakest members.’

St Lucy

In early Norwegian Christianity, churches were sometimes built on sites used for pagan sacrifice. Thus traces left by heathen contamination were cleansed; thus, too, one showed that faith in Christ brought obscure presentiments of battles between good and evil to luminous fulfilment. Something similar happened to the tradition of St Lucy. Lussi-Night was an established notion in medieval Scandinavia. A female demon named Lussi was thought to haunt the world on this, the year’s longest night, an outburst of evil on the threshold of Christmas. This nocturnal witch found her match in Lucy, whose name means ‘light’. The historical Lucy was born, we are told, in Sicily in 283. Enchanted by the beauty of the Gospel, she consecrated herself to Christ. Her resolve met incomprehension, but she kept it. She preferred death to being robbed of freedom to be faithful. Lucy was a young girl. But she prevailed, in her outward fragility, over dark violence by enlightened Christian fidelity. In this our Norse ancestors found a source of hope. So may we.

Ascesis of Joy

Do we think it hypocritical to perform an action not in tune with our spontaneous emotion? If so, let us remember that feelings are to a large extent formed by actions we freely decide to perform or not to perform. Resolve is a key quality in our moral and spiritual life. Think of sport. Not many of us are ready, just like that, to run a marathon. We need to get into shape over time. We live at a time, in a country, in which there is a gym at every street-corner. We know how effective regular physical exercise can be. Should we take our spiritual exercise less seriously? That would be irresponsible and unwise.

From my Pastoral Letter for Advent

Precociousness

The legendary Beethoven interpreter Rudolf Buchbinder declared, ‘From my fifth year, one thing was crystal clear to me: I wanted to be a pianist’. He admits he had a moment of doubt at eight or nine, when he thought of becoming a conductor (‘perhaps I dreamt I’d then have to practise less’), but this faithlessness was of short duration. He stuck to his first inspiration and seems not, 60 years on, to have regretted it. We’re wary, now, of letting children make momentous decisions too early. They must see the world! There is wisdom in this. But I wonder: do we take sufficiently seriously the clarity children often have about what matters in their lives, what doesn’t? Thérèse of Lisieux, a doctor of the Latin Church knew from a very early age that she had to be a nun, and fought to realise that aspiration. What would she have been told today? To get a degree in management consultancy first, to acquire a taste of ‘real life’? Or at least to take a gap year travelling round the Far East? Perhaps the Holy Spirit would not raise up a Thérèse of Lisieux now. But what if he did?

Finding Balance

Some lives are so rich in experiences, contradictions, tensions, sufferings and joys that they do not seem to fit into a single biography. Such is the life of Zhu Xiao-Mei. Her autobiography, patterned on the Goldberg Variations, tells the story of an exceptional musical talent crushed by China’s cultural revolution, yet not extinguished. The account of how, in the re-education camp of Zhangjiako, she found an accordion used for a propagandist show, then managed to draw from it (and from the recesses of memory) Chopin’s Second Etude, opus 10, is proof of the human spirit’s resilience. From that moment, she who seemed to have lost everything, even her sense of self, was again ‘haunted by music’, especially that of Bach, which displayed to her the possible integration of opposites in harmony, balance, beauty. ‘If one has much to say, in life as in music’, writes Zhu Xiao-Mei, ‘one must take the time to say it.’ Thank God, she does. If you have not heard her Goldberg Variations, do listen. And hear her speak about them in Michel Mollard’s The Return is the Movement of Tao.

Wisdom

‘Wisdom is vindicated by her deeds’ (Mt 11,19). What is that supposed to mean? Jesus’s words spring from perplexity regarding ‘this generation’. We ascertain that a Palestinian context 2,000 years ago has much in common with our own. Today, too, it is a risky business to predict the response of the masses and to wish to please. Good PR is important, but has its limitations. At the end of the day, sincerity is more effective. Our Lord impressed people by his ‘authority’, we are told. The term (ἐξουσία) could even be rendered, I’d say, as ‘integrity’. What Jesus said and his outward gestures were at one with his being, with who he was. Therefore people listened even when he said things that cut across their expectations. Good Christian communication is not primarily about publicity hypes. It is about trustworthiness. Wisdom speaks for herself, if only it finds expression in us, through us.

Immaculate

Formed as we are to a scientific mindset, we think of the way things happen in terms of cause and effect. You flick a switch and the light comes on. Interest rates rise, and consumer habits change. Factories in Newcastle send out noxious fumes, and Norwegian reindeer go bald. Our gadgets, our economy, our fragile ecosystem: all seem to obey this fundamental law of causation. It is easy to assume that it’s simply the way things are. Let’s be wary of that assumption, especially in matters of theology. Today’s feast, crucial to the unravelling of our redemption, rejoices in effects that precede their cause. The Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary is not some myth of romantic purity removing the Mother of God from humanity’s common run whose stains we know all too well. The message of this feast is not that Mary did not need to be redeemed. On the contrary, she is, we might say, more redeemed than anyone else, the recipient of a unique outpouring of grace.

From a homily for the Immaculate Conception

Time to Read

Ambrose of Milan — bishop, statesman, poet — was an exceptionally busy man. Yet he knew how to be still. I am always touched by Augustine’s description of him in Book VI of the Confessions. Augustine was no respecter of persons. Yet there is awe in his account of this man who so deeply influenced his life: ‘Often when I was present—for [Ambrose] did not close his door to anyone and it was customary to come in unannounced—I have seen him reading silently, never in fact otherwise. I would sit for a long time in silence, not daring to disturb someone so deep in thought, and then go on my way.’ This passage, often cited as a clue to the reading habits of Antiquity (reading aloud was clearly the norm), reminds anyone in leadership of how important it is to keep up determined, concentrated study in the midst of all other the claims on one’s attention. ‘Let no vain or unmeaning word issue out of your mouth’, wrote Ambrose to the newly appointed bishop Constantius. To heed that counsel, one must constantly re-ground oneself in intelligent statements of essentials, nurturing, forming and setting a standard for one’s own intellect.

Missed Opportunity

Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites is an opera based on a play by Bernanos based on a short story by Gertrud von Le Fort based on a true story. It must be the most thoroughly theological piece in the repertoire of grand opera. Anyone who comes fresh to Emma Dante’s production at the Opera di Roma would never guess. Why her Carmelites are dressed like low-cost Queens of the Night, obligatorily limp, and wear blue surgeon’s gloves, I’ve no idea. The singing is excellent. Michele Mariotti directs the orchestra masterfully. But what a trial for the musicians to perform this fine work in a largely imbecile production. Such Christian symbolism as occurs is used so nonsensically as to be rendered silly, as if one had staged Turandot in the style of Little Red Riding Hood, with the wolf in a kimono. It is a missed opportunity – and a reminder that it matters to acquire and intelligently pass on symbolic literacy. What a contrast with Riccardo Muti’s landmark production of 2004, not to mention Dervaux’s version with Poulenc’s original cast, available as an audio recording in the Internet Archive.

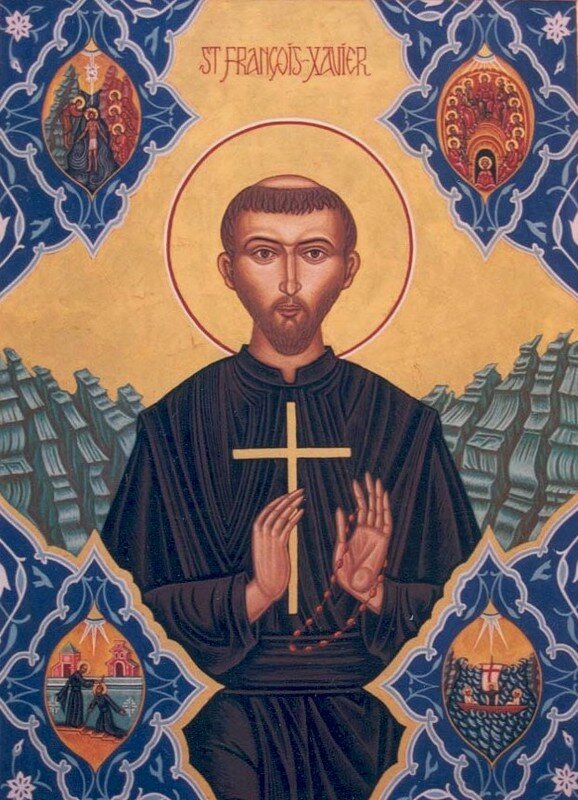

Mission

Francis Xavier’s ministry was not one of constant success. A telling incident occurred in 1551. After several months’ effort in Yamaguchi without making a single convert, Francis’s companion Fernandez was teaching in public one day when a man came up and spat in his face. Fernandez calmly wiped his face, and continued preaching. Faced with this spectacle, one of the Jesuits’ bitterest enemies converted to the faith and asked for baptism. Within a few weeks the local Church counted many converts. We’re given to complaining, today, that society does not want to hear the Christian message. What is it, though, that niggles us? Is it that Christ is unknown? Or is it our sense that no one appreciates us and our once-prestigious institutions? Often our motives are mixed. Therefore it is important to examine them. We are called to cast fire upon the earth. Let’s make sure our hearts are set on doing just that, not on restoring tatty Christmas lights to adorn our own houses. If the world spits on us, our response may reveal the face of Christ more effectively than any preaching. The Lord exhorts us, ‘You received without charge, give without charge’. So that is what we must do. (From Entering the Twofold Mystery).

Blindness & Sight

Blindness is a leitmotif in Scripture. It can result from illness, as in the case of Bartimaeus. In such cases intervention from without is required for healing. Isaiah presents us with blindness of a different kind, resulting from immersion in shadow and darkness (29:18). Those smitten with it must step out of the murk first; otherwise no one can help them. Even healthy eyes are blind in a closed, lightless place. There’s a risk that we get used to such blindness, which does have its comfortable aspect. What I cannot see or choose not to see (in myself or around me) cannot require a response; by closing my eyes I protect myself from needing to exercise my freedom. The Gospel would make of us seeing women and men, that is, realists without illusions yet on fire with invincible hope. When we raise our eyes and meet the gaze of God, which sees us everywhere, we discover the one perspective that renders this world intelligible: we see the universe embraced by immense charity made up, at once, of justice and mercy. Ubi amor, ibi oculus. For our eyes to see clearly, our heart must be freed, widened, enabled to love.

Our Lady of the Snows

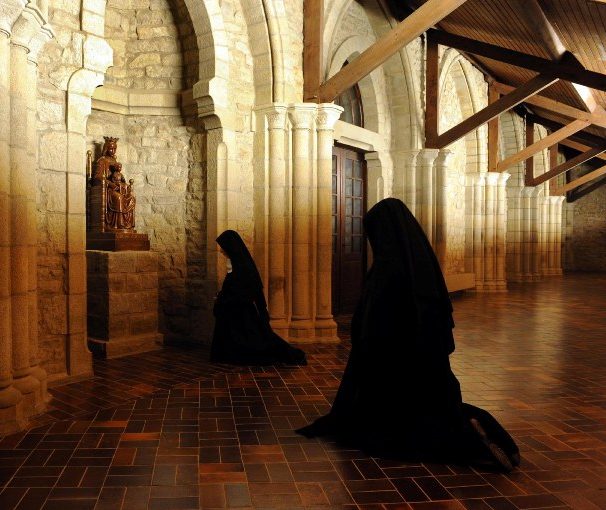

‘I have rarely approached anything with more unaffected terror’, wrote Robert Louis Stevenson in Travels with a Donkey in the Cévennes, ‘than the monastery of Our Lady of the Snows.’ Such is the effect a house of God can have. Yet on closer acquaintance this Trappist abbey, where Charles de Foucauld would later begin monastic life, appeared to him full, not only of eccentrically lovable people, but of intrinsic attractiveness. Stevenson went on his way, he records, ‘with unfeigned regret’. Today something remarkable happened in Our Lady of the Snows. Having been home to Trappist monks for 172 years, it changed hands and was taken over by Cistercian nuns from the thriving abbey of Boulaur in the Gers. Sending the foundresses off yesterday, Mother Abbess said: ‘May they attract numerous vocations so as to found in their turn’. It may seem over-daring to charge a not-yet-founded community with the task of founding – but no, such is the logic of being fully alive: we receive the gift of life, natural and supernatural, to pass it on; our task is not only to flourish, but to bear fruit. Were we more alert to this fact, much in the Church (and indeed in the world) would look different.

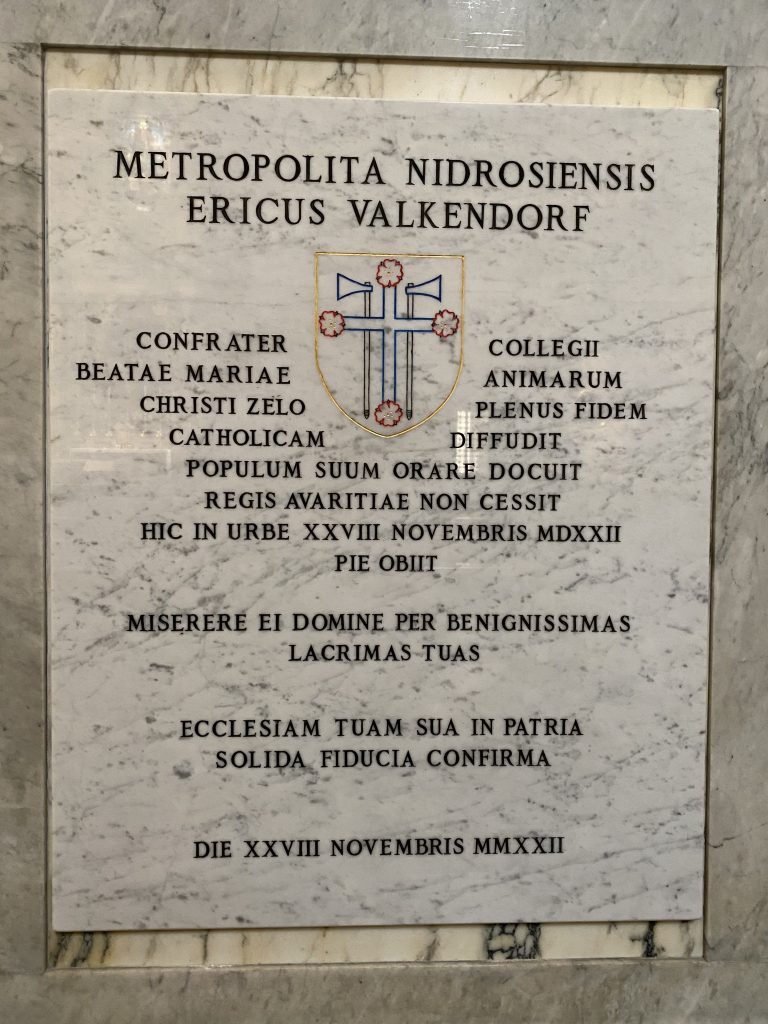

A Valiant Bishop

500 years ago, on 28 November 1522, the Metropolitan Erik Valkendorf died in Rome. He had come to seek the support of the Holy See against the pretensions of King Christian II. This penultimate archbishop of Nidaros, whose destiny strikingly resembles that of Thomas Becket, had commissioned the Missale nidrosiense (1519) for use throughout his province, which embraced, not only all of Norway, but Greenland, Iceland, the Orkneys, and the Isle of Man. He prescribed this prayer for recitation by all his priests before the celebration of the Sacred Mysteries: ‘Grant me, Lord, inward tears with strength to cleanse the stains of my sins and fill my soul with heavenly gladness always. I pray you, Jesus, by your own most kind tears: grant me the grace of tears which, apart from your gift, is beyond me. Grant me a fountain of tears that will not dry up, that my tears may be my bread by day and by night. Prepare this table for your servant in your sight that it may strengthen me. I desire to eat my fill of it daily.’ This evening’s Vespers at the Collegio dell’Anima, of which Valkendorf was a member, can be found here, a brief video-summary here.

Awake the Dawn

If we are privileged to pray the Divine Office according to the order prescribed by St Benedict, Vigils of Saturday present a tremendous panorama. The set Psalms take us on a tour from the creation of the world through the history of Israel to a glimpse of the world to come: ‘I shall awake the dawn’.

It is good to be reminded that history moves towards a goal.

As Sr Elisabeth Paule Labat once wrote: to the extent that man grows in wisdom he ‘will perceive the history of this world in whose battle he is still engaged as an immense symphony resolving one dissonance by another until the intonation of the perfect major chord of the final cadence at the end of time.’ Advent invites this year, as every year, to attune our hearing, to establish ourselves in inward silence. Thus we may perceive the perplexing modulations formed about us now as stages in an ongoing melodic development whose climax will be glorious.

Try Proust

In a recent video Fabrice Hadjadj reflects on visual media. With panache and economy of means he lists strategies intended to keep us hooked. He speaks of what has become a near-universal anxiety: the fear of missing out. We are vulnerable to algorithms designed to seduce us by means of a perfect mixture of stimulus, suspense, and reward. What does it do to our general outlook on life to watch quantities of little videos with only highlights and no dramatic development to speak of? ‘Over-excitement anaesthetises you. Your attention span is in pieces. Bombarded with news items, you are better informed, no doubt, but you’ve lost your ability to think. A sentence by Proust becomes unreadable to you. A dialogue by Plato seems to you too long.’ What to do then? ‘Disconnect!’

It may be advisable to read a page of Proust from time to time to verify if the time has come to follow this counsel.

Forward & Upward

In his account from 1768 of A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy, Laurence Sterne evokes an encounter with a Franciscan begging for alms. Sterne disapproved of the exercise. He was firmly resolved ‘not to give him a single sous‘. Yet he was intrigued by the man, above all by his eyes ‘and that sort of fire which was in them’. The friar’s head, he wrote, ‘was one of those heads which Guido has often painted,—mild, pale—penetrating, free from all commonplace ideas of fat contented ignorance looking downwards upon the earth;—it look’d forwards; but look’d as if it look’d at something beyond this world.—How one of his order came by it, heaven above, who let it fall upon a monk’s shoulders best knows: but it would have suited a Bramin, and had I met it upon the plains of Indostan, I had reverenced it.’ The notion of ‘fat contented ignorance looking downwards upon the earth’ is dispiriting. We need to meet people who direct our gaze forward and upward. Perhaps, by God’s grace, we may even be such to others.

Listen to Your Heart

‘You should only listen to your heart!’ This is the message of Cristina Scuccia, until recently the world’s best-known religious sister, now a waitress in Spain, as one can read in the report, Italy’s singing nun casts off her veil. ‘You should only listen to your heart!’ It sounds great; but is in reality an ambiguous counsel. What if my heart tells me one thing today, another tomorrow? Anyone who has lived more than a half-conscious life knows that Jeremiah, when he wrote, ‘the heart is deceitful above all things’ (17:9), wasn’t just engaging in prophetic hyperbole. The heart isn’t spontaneously faithful. It pulls us in different directions, susceptible to ephemeral charms. St Cecilia, whose feast it is today, prayed: ‘Let my heart be immaculate, lest I be confounded’. That is a wholly different approach. It involves the ascesis of letting my heart be cleansed before I trust its inspirations. Living in this way taught Cecilia steadfastness to the point of martyrdom. It made her a saint.

Christ the King

Do I so fully live in the Spirit that I can say, with regard to every aspect of my life, ‘Jesus is Lord’? Do I acknowledge Christ’s lordship over my instincts and appetites? Or do I keep pockets sewed up for private use, indulging desires, dreams, and imaginings I have formally renounced? Is Jesus Lord over my passions? Or do I sublet areas to myself, breathing on embers of resentment, enjoying the bitter draught of anger? Is Jesus Christ—the same yesterday, today, and forever—Lord of my past and future? Or do I hug achievements, experiences, pleasures and hurts of distant years, while making plans for a tomorrow not my own?

Literature & Life

Ours is a time of loneliness. A year or so before I left the UK, the government appointed a Minister of Loneliness. A state department was called for. We’re aware of great needs in mental health, not least among the young. I shan’t attempt to formulate a universal diagnosis. God save us from clerical psycho-quackery! That said, it’s part of a bishop’s job to interpret societal crises from a spiritual point of view. I maintain, after all, that the spiritual life stands for something real and substantial, carefully aligned to, but not to be confounded with, psychological life. I dare to say this: I think existential superficiality, conceptual impoverishment, and a loss of words are a risk to public health in our time. We live at a great depth; we experience and feel deeply: that’s the way we are. But fewer and fewer have words with which to designate the depths that, by virtue of existing, they touch. So they are vulnerable to offers of simplifying labels, even of re-labelling. In order to live — to survive — we must reach a certain depth of consciousness, there to encounter ourselves and others, to make sense of joy and pain.

From a talk in Norwegian, here, on ‘The Power of Words’.

Humour

In his memoirs, Louis Bouyer wrote about what made him laugh. ‘I should add that all my teachers would later tell me of the superiority of character-driven comedy over situation comedy never managed to uproot from me every child’s conviction: that those who hurl cream pies at each other’s faces are funny in a far more relaxing, and, therefore, at bottom far more satisfying way, than the more subtle forms of what is called ‘wit’. In fact, it is quite remarkable that these latter forms usually grow stale in less than a generation.’

This explains why, say, a Louis de Funès, whether engaging in off-road driving, singing in choir, or speaking a range of foreign languages, has a far more durable appeal than any amount of intellectual comedy.

Which is not to say that what he represented was superficial. If you’re in doubt, just look at him here, attending to Madeleine Renaud reading Claudel’s La Vierge à midi.