Barbarians

In the first episode of BBC’s Civilisation from 1969, still intensely watchable, Kenneth Clark sits below a Roman aqueduct wearing a very English suit, citing Cavafy. He has just asked what civilisation’s enemies are. He gives a threefold answer: fear, boredom, and hopelessness, ‘which can overtake people with a high degree of material prosperity’. That’s where Cavafy’s Waiting for the Barbarians comes in. In it the poet evokes a late antique city in a state of apathy, every day awaiting the arrival of barbarian hordes expected to turn life upside down. In the end, though, the barbarians don’t turn up; they have directed their course elsewhere. The city’s inhabitants respond with spontaneous disappointment. Cataclysm would have been better than nothing. ‘Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians?/Those people were a kind of solution.’ For a civilisation to thrive, says Clark, it needs, above all, confidence: the sense that life is worth living, that children are worth having, that the future is worth constructing. That’s every bit as true today as 53 years ago. Only, since then our store of confidence has shrunk.

Service

The last phrase of today’s Gospel, ‘We are useless servants, we have done only what was our duty’, may seem harsh. Is the servants’ work then valueless? Only if we see it from our society’s perspective, in which service is perceived as demeaning and everyone wishes to be his or her own boss. If, meanwhile, we are in the service of a Master who is supremely good, loveable, creative, and resourceful, awareness of our objective uselessness is no tragedy; on the contrary, such awareness will make us overjoyed that we can nonetheless be employed to produce something beautiful and lasting, almost despite ourselves. To do our duty then will be glorious, an honour.

Such servants we are called to become.

East & West

Some thirty years ago, Jaroslav Pelikan remarked: ‘It has been evident to Western observers since the Middle Ages that Eastern Christianity has affirmed the authority of tradition more unambiguously than has the West. Repeatedly, therefore, it has been the vocation of Eastern Christendom to come to the rescue of the West by drawing out from its memory the overlooked resources of the patristic tradition. So it was in the beginning of the Renaissance in Italy, when the scholars of Constantinople fled to Venice and Florence before the invader, bringing their Greek manuscripts with them […]. And so it has been again in the twentieth century. One of the most striking differences between the First Vatican Council and the Second – and a difference that helps to provide an explanation for many of the other differences – is that between 1870 and 1950 the Western Church had once more discovered how much it had been ignoring in the liturgy and spirituality, the theology and culture, of Eastern Christendom.’

And today?

De bono mortis

A couple of weeks ago, on my way from Santa Cecilia to Santa Maria in Trastevere, I noticed this graffito. It’s difficult to know what’s behind it, irony, serenity, or even a kind of perversity. The only perspective in which such a statement, I’d say, can be said to make sense is the perspective of faith. St Ambrose provides it in his treatise entitled, De bono mortis, ‘On Death Considered as a Good’. He says: ‘The Lord suffered death to make its surreptitious entry [into life] to make guilt cease. However, lest the finality of nature should appear to reside in death, the resurrection of the dead was bestowed. Thus guilt would be brought to an end by death, while nature, through the resurrection, would be rendered eternal.’ We need to keep reminding ourselves of this, that death just isn’t natural and that our nature therefore, knowing itself albeit subliminally to be made for unending life, rebels against it.

Thank You, Beethoven

Han-Na Chang introduced this evening’s performance by the Trondheim Symphony Orchestra reading a passage from Beethoven’s Heiligenstadt Testament. The text, written in 1802, expresses the composer’s deep distress at his increasing deafness. Indeed it reveals hopelessness. Remember, he was only 32 at the time: ‘what a humiliation when one stood beside me and heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing […], such incidents brought me to the verge of despair, a little more and I would have put an end to my life.’ He was withheld from this drastic decision by the imperative of creation: ‘it seemed impossible to leave the world until I had produced all that I felt called upon to produce’. Having finished reading, Han-Na Chang said: ‘Beethoven, what happened to you? You decided to live. Thank you.’ Then she raised the baton. That same gratitude vibrates within me at the end of a glorious concert, the music still resonating in my ears.

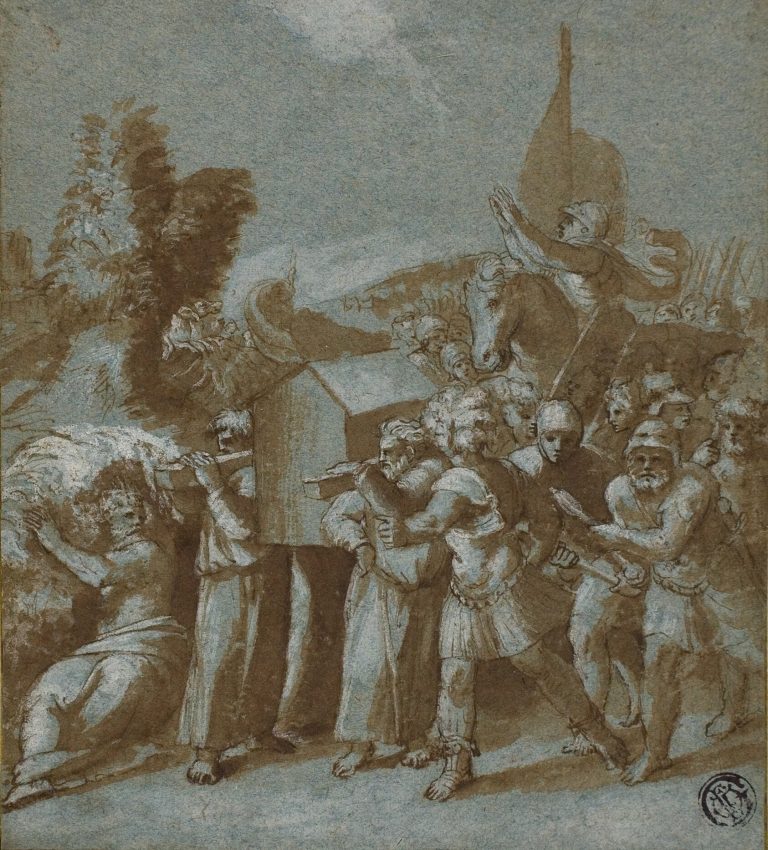

Isaac’s Wells

To be a Catholic, as far as I can see, is to steer clear of excesses, be they progressive or regressive. What matters is to receive the fullness of tradition in order, with gratitude and humility, to pass it on undiminished. The noun traditio, let’s not forget, primarily indicates a dynamic process.

In times marked by corporate amnesia, many young people naturally wish to drink deeply from the sources of the past. That is good. We are called to emulate the example of Isaac, that mysterious patriarch who spent much of his life unstopping the wells, dug by his father Abraham, which the Philistines had filled with gravel to prevent the Israelites’ flocks from thriving. But tradition no less calls on us to be prospective. A Christian is one who is in forward movement.

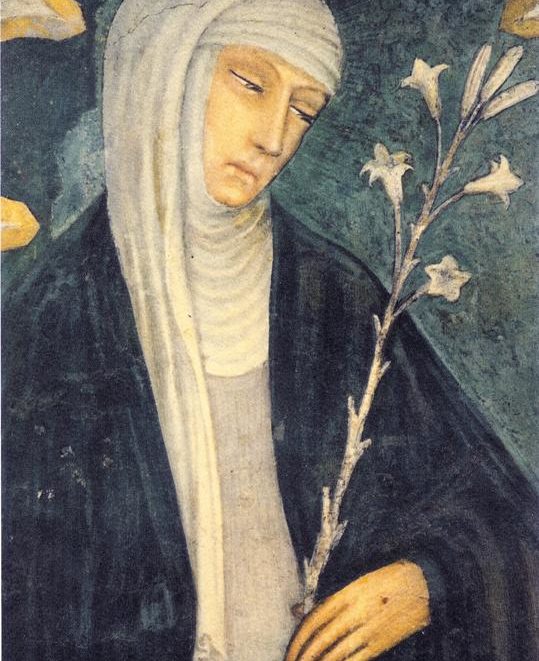

Frail Goodness?

Martha Nussbaum once wrote a book with the incomparable title, The Fragility of Goodness. Once you’ve heard the phrase, it stays lodged in the memory. Often enough the good seems terribly fragile. That is when it matters to walk, not by sight but by faith, believing firmly in the supreme Goodness that bears all things. In the Dialogue, Catherine of Siena heard the Lord say: ‘I wish to act mercifully towards the world and to provide in all circumstances for my creature endowed with reason. Ignorant man, though, turns into death what I give for the sake of life; thus he makes himself cruel to himself. I always provide, and I tell you that what I have given man is highest providence. With providence I created him; and when I looked into myself, I fell in love with the beauty of my creature’ (c. CXXXV). On this account, even our destructive inclinations result from a perversion of the good, which it matters to catch sight of in order to reorient our energy towards it. Further, a gaze of love – suffered love – rests upon us even in our rebellion. If only we would awaken to it.

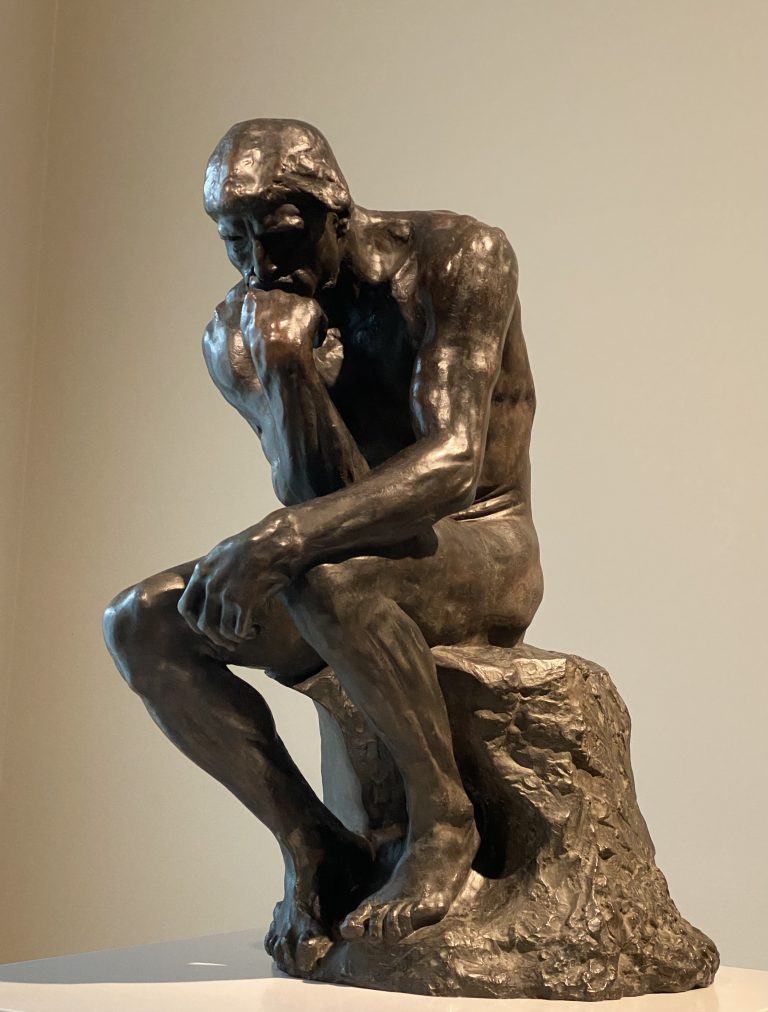

Wisdom’s Quickness

Today’s Vigils reading (Wisdom 7,15-30) offers an extravagant list of adjectives describing Wisdom. To give an account of the ineffable, we have two options, accumulated repetition or reverential silence. Theology’s principal sources, the Scriptures and the sacred liturgy, give examples of both. Within Wisdom, we are told, is ‘a spirit intelligent, holy, unique, manifold, subtle, active, incisive, unsullied, lucid, invulnerable, benevolent, sharp, irresistible, beneficent, loving to man, steadfast, dependable, unperturbed, almighty, all-surveying, penetrating all intelligent, pure and most subtle spirits; for Wisdom is quicker to move than any motion; she is so pure, she pervades and permeates all things.’ In the West, Wisdom has come to appear ponderous, personified by bearded sages. Biblical Wisdom, meanwhile, is fleet-footed and gracious, chaste but peaceful, not anxious. It has an edge, being sharp, yet is philanthropical. A broad semantic field opens up before us waiting to be rediscovered and delighted in.

Memory for Blessing

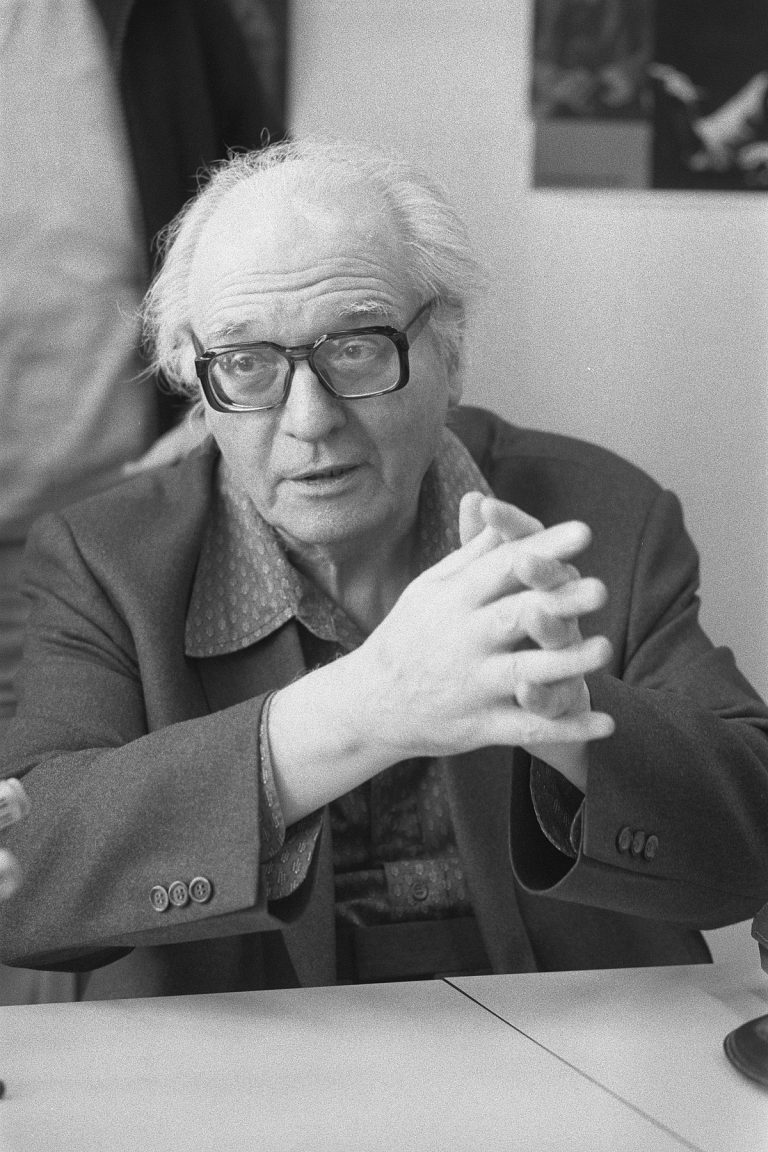

Anne Applebaum wrote of Linda Kinstler’s Come to this Court and Cry that it ‘reminds us of the dangerous instability of truth and testimony, and the urgent need, in the 21st century, to keep telling the history of the 20th’. For the past 75 years, remembrance of the Shoah has maintained a certain standard in Western historical consciousness. Are we aware of what is at stake now that there is hardly anyone left to recall and bear witness? Documented testimonies assume new significance, such as this 2006 portrayal of six Norwegian Holocaust survivors, including the noble Mr Jo Benkow, from 1985 to 1993 Speaker of Norway’s Storting. The last word in the film is given to Jenny Wulff (1921-2009), whose family perished in German camps: ‘When you need someone to console you, there’s no one there.’ To keep the memory of absence alive is now a moral imperative.

Up to Date

Ten years have passed since Martin Mosebach mused about Catholic bishops: ‘It is as if they have forgotten that the Church is very old and that she has survived many societal systems and upheavals throughout history and that, in many centuries, she was not completely ‘up to date’. Least so at the time of her foundation in late antiquity, in an urbanised, enlightened, multicultural, atomised and individualised society which, by a slow process, she permeated and transformed.’

Thinking people at a distance from the Church are apt to ask themselves, Mosebach contends (with customary poignancy and elegance): ‘Should they see [the Church] as dangerous or possibly as the only remaining alternative to secular society?’ The jury, I’d say, is still out.

Meaning through Form

In an essay on the art of M.C. Escher, Maria Popova explores the interface between music and visual art. Experiencing deep loneliness as a result of the fact that he was ‘beginning to speak a language these days only very few understand’, Escher found sudden, freeing enlightenment in the Goldberg Variations.

‘It wasn’t until he heard Bach’s Goldberg Variations that his mind snapped onto its own gift for rendering meaning through form. ‘Father Bach’, he called him. Wonder-smitten by Bach’s music — by its mathematical figures and motives repeating back to front and up and down, by the majesty of ‘a compelling rhythm, a cadence, in search of a certain endlessness’ — Escher felt in it a strong kinship, a special ‘affinity between the canon in the polyphonic music and the regular division of a plane into figures and identical forms.”

Recognisable Joy

In his thoughtful, exquisitely illustrated account of a visit to Mount Saint Bernard, Mark Dredge says of one of my brothers, ‘It takes me a couple of days to sense that his calmness comes with something deeper, a profound contentment and happiness which I come to recognise as joy.’ What a wonderful testimony is joy! And how marvellous that a monastic brewery provides an occasion to share it! I still believe beer-making can reveal something of the mystery of the Church. By being refined to manifest their choicest qualities; by being brought together in a favourable environment; by mingling their properties and so revealing fresh potential; by being carefully stored and matured, the humble malt, hops, yeast, and water are spirit-filled and bring forth something new, something nurturing and good, that brings joy to those who share it. Considered in this perspective, the brewery provides us with a parable for monastic life, with the Lord as virtuoso brewmaster. The Scriptures favour wine as an image of the Gospel—but that is culturally conditioned; beer, it seems to me, is a much-neglected theological symbol. – Temperance in enjoyment, needless to say, is taken for granted!

Martyrium

Rome’s Pontifical Minor Seminary moved to its present quarters on the Via Aurelia in 1933. The apse painting in the principal chapel is a scene straight out of Sienkiewicz. It bears the inscription, ‘Hail flowers of the martyrs, sons of the apostles; by whose outpoured blood and by flames Rome was lit up’. The reference is to Nero’s ghastly action after the city fire of 64, when the emperor, who had probably been behind it, blamed the nascent Church and had crucified believers lit as torches round his garden. It strikes one that not so long ago it was considered opportune to raise young people in the faith by putting before their eyes the witness of the martyrs. Indeed, the lads who first prayed before this scene would, a decade on, as young priests, have to make courageous choices. Are young Italian Catholics now invited to contemplate themselves in the protomartyrs? I think of an English parallel. Just thirty years ago, I’d say, the witness of the martyrs was central to the self-image of English Catholics. Today that memory seems to have been eclipsed. One wonders how that happened. And why.

Letting Go

In his incomparable fresco of the Last Judgement at Santa Cecilia in Trastevere, Cavallini depicts the ascending orders of angels. As they rise, they become less embodied, more ethereal. Thus a subtle theological truth is rendered visibly. To draw closer to God is to be conformed to him, to participate progressively in his nature. To assert this is not to indulge in over-audacious speculation; it is to put faith in divine promises, ‘that by these you may be made partakers of the divine nature’ (2 Peter 1:4).

There is much that is positive in the contemporary culture of celebrating the human body. From a Christian point of view, though, this outlook runs the risk of being limiting. It curtails aspiration. It keeps us from learning the high art of self-abandonment. That is probably why our times find it hard to face death, which marks such an obvious letting-go intended to be freeing, yet frightening in the extreme if our sense of self is exclusively bound to what we know we must leave behind.

Is that enough?

Today, the feast of the great St Teresa, marks the centenary of the birth of Don Luigi Giussani. He continues to inspire countless people to radical, intelligent discipleship. I recently came across an exchange Giussani once had, on his way to give a lecture, with a journalist. Huge crowds were waiting. The journalist asked: ‘Why are all these people waiting for you?’ Giussani replied, ‘Because I believe in what I say.’ – ‘Is that enough?’ – ‘Yes.’ It’s good to be reminded of this from one who was a stranger to all gimmick. Cardinal Ratzinger preached at Don Giussani’s funeral. He stressed Giussani’s keen sense of Christianity as an encounter, an event. The secret of his efficacy as a teacher, educator and helper of the poor was his being always turned towards that encounter, well aware that ‘as soon as we substitute moralism for faith, doing for believing, we fall into particularisms; we lose our criteria and sense of orientation, and in the end we do not edify, but divide.’

A Dog’s Life

Elizabeth Lo’s film Stray is stirring and impressive. Ostensibly recounting a dog’s life in Istanbul, wittily interspersed with ancient quotations about the interface of human and canine existence, it in fact proposes a probing account of our world’s values, or lack of such.

Dogs provide a lens through which to contemplate human society. Through them we see human beings – children – treated like stray dogs. The stark absence of sentiment only makes Lo’s statement clearer. She calls her work ‘a critical observation of human civilisation’.

Sometimes it takes animals to recall us to our humanity. Thank God we’ve got them.

A Shudder

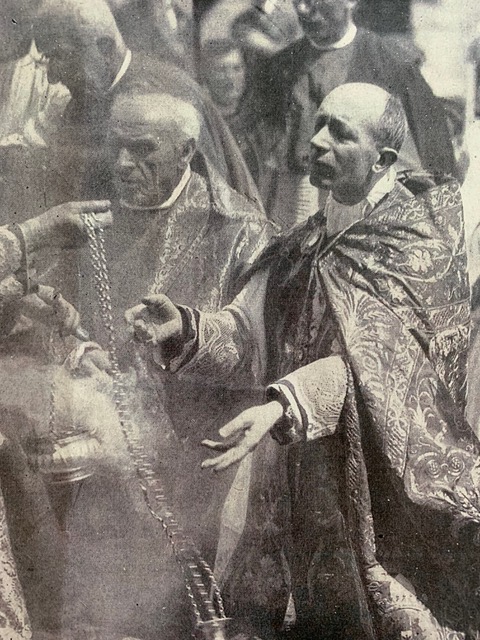

The Second Vatican Council taught: ‘In the earthly liturgy we take part in a foretaste of that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem toward which we journey as pilgrims, where Christ is sitting at the right hand of God’. The phrase makes me think of a photograph I like to keep within reach. It shows the monk-archbishop of Milan, Blessed Ildefonso Schuster, as celebrant. It shows a man transfigured, wholly surrendered to the sacred act, in symbolic and embodied continuity with the heavenly host. Schuster was a man of slender, fragile appearance. Vested for the liturgy, though, he became a giant: ‘We witnessed a holy colloquy with the invisible power of God; it was impossible to behold him without succumbing to a religious shudder.’ Arguments about worship go on and on. The decisive question to be asked, however, is surely this: Who, now, celebrates the sacred liturgy on such terms? We might recall that Schuster used to say: ‘It seems people are no longer convinced by our preaching, but faced with sanctity, they still believe, still kneel down and pray.’

Sursum corda

I recently had occasion to cite an insight of which I am convinced: ‘Anthropocentrism kills the Church and its life.’ How to get out of the rut? We’re told in this morning’s vigils reading, one of my favourite texts in the liturgical cycle. The Irish abbot Columbanus (ca. 543-615) asks how God’s light may shine in him and so illumine others? His answer is formulated as a prayer: ‘I beg you, my Jesus, fill my lamp with your light. By its light let me see the holiest of holy places, your own temple where you enter as the eternal High Priest of the eternal mysteries. Let me see you, watch you, desire you. Let me love you as I see you, and before you let my lamp always shine, always burn. Let us know you, let us love you, let us desire you alone, let us spend our days and nights meditating on you alone, let us always be thinking of you. Fill us with love of you, let us love you with all the love that is your right as our God. Let that love fill us and possess us, let it overwhelm our senses until we can love nothing but you, for you are eternal.’

Wealth

At the end of Olivier Mille’s documentary portrait of Messiaen, the composer speaks of his oratorio Francis of Assisi. He’d been reproached for it, he says, by right-minded people objecting that St Francis had been poor whereas Messiaen’s orchestration, colours, and rhythms are incredibly rich. The composer gives the following response:

‘St Francis was totally poor, that is true. Yet he retained a child’s capacity for wonder. He was in awe before all the beauty that surrounded him. So he was rich! Rich in sunlight, rich in the stars, rich in flowers, rich in birds, rich in the sea, rich in trees, rich in all that surrounded him. That’s immense wealth – and it is’, adds Messiaen, ‘something I wish you all.’

Belonging

By being abstracted from belonging (belonging in a culture, in a religion, in a gender, in one’s own body), the individual is surrendered to itself on the basis of self-defined psycho-sexual criteria. The surrender reflects the mentality of our time —our wish to create ourselves. It is presumed that there is no such thing as meaningfully mediating institutions. Cultural experience, meanwhile, shows that the self-understanding of women and men tends to develop precisely through community. Hardly any other epoch has had a view of human nature as atomised as ours. This view is upheld in full awareness that loneliness is a growing societal ill, especially among the young. The law proposal shows a lack of historical consciousness. As a society, driven by the state, we are asked to capitulate before an understanding of human nature that will turn out to be ephemeral.

From a Statement on Conversion Therapy.

St Francis & the Viol

So vivid are the accounts of St Francis’s personality that we risk forming an impression that is purely this-worldly. Francis is held hostage to more pragmatic causes than any other saint. It matters to recall with reverence the supernatural foundation of his life and witness. The Fioretti speak of an incident that took place not long before his death. Weakened by abstinence and spiritual trials, Francis turned his mind to meditation on celestial joy. ‘Now while this thought was in his mind, suddenly an angel appeared to him in surpassing glory, having a viol in his left hand and a bow in his right. And St Francis stood in amazement at the sight, the angel drew the bow once across the strings of the viol, when the soul of St Francis was instantly so ravished by the sweetness of the melody, that all his bodily senses were suspended, and he believed, as he afterwards told his companions, that, if the strain had been continued, the intolerable sweetness would have drawn his soul from his body.’ Here we glimpse the soul-mystery of this singular Christian, whose being was wholly attuned to the music of eternity.

Called to Fidelity

Today’s Gospel gives us the parable of the good Samaritan, a criterion by which we must measure ourselves. Are we naturally inclined to act like the priest and levite? Do we, to avoid others’ needs, cross the street and vanish into the cityscape on the other side? Perhaps we think, ‘I can’t’ or ‘I daren’t’. Right action in extreme conditions isn’t necessarily spontaneous. Such action must be prepared by other, small choices made in secret, the sort of choices of which life consists in the main. Let’s remember: each small action carried out in the name of Jesus, for his love’s sake, can be a source of sanctification. It can prepare us for big choices lying before us, choices as yet unknown on which others’ thriving will depend. We must practise fidelity, then, in daily circumstances, in whatever task God’s providence entrusts to us now. If we get used to saying Yes! in that setting, we shall be armed for greater trials, too. Then God’s Spirit will be free to work in us. By grace we shall acquire the mind of Christ. ‘It is no longer I who live’, writes St Paul, ‘but Christ who lives in me.’ What he means is: It has become natural for me, now, to walk as he walked. May God grant us, too, grace to reach that point of identification.

Bitter & Sweet

Michael Leunig has a gift for putting his finger on things. He is almost always enlightening, often funny, sometimes infuriating. He can both write and draw with tenderness.

Here is an autumn prayer from his collection The Prayer Tree:

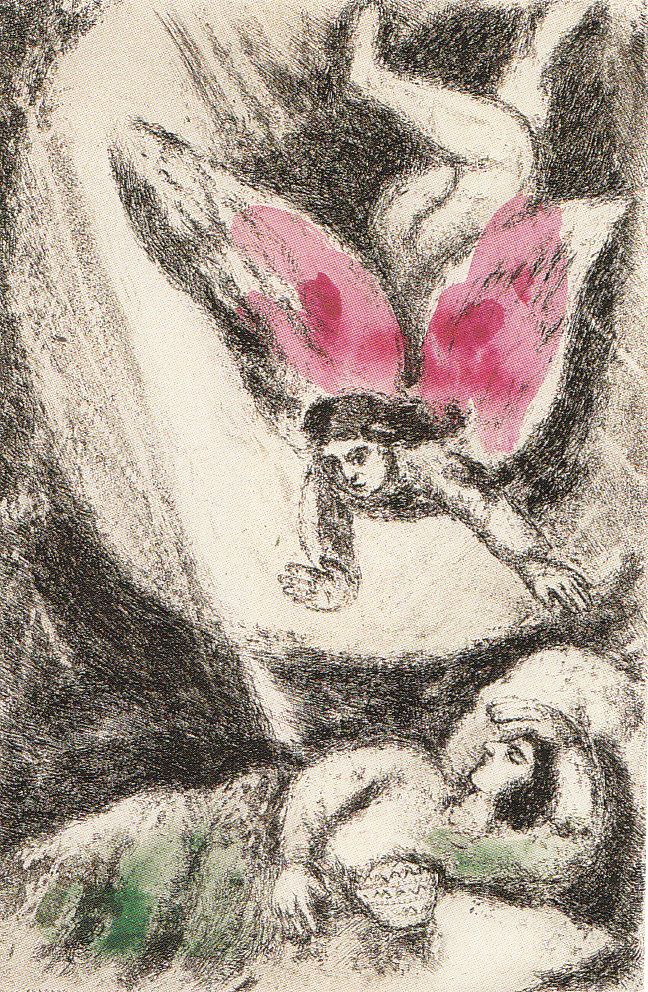

No Truck

A great deal of nonsense is often said about angels. We may find we’re given to thinking nonsensically about them ourselves, haunted as we are by images of feathers, celestial chariots, and cascading cloaks.

So earthbound are we poor human clods, so conditioned by our bodies, that it is hard for us to conceive of pure spiritual existences.

Another hurdle that separates us from the angels we celebrate today is this: they have no truck with sin, no experience of it. They can distinguish between good and evil with perfect clarity, whereas we, often enough, are captive to deadly ambiguities, not knowing, sometimes not wanting to know, what’s what.

Law & Parables

There’d be much to say about Linda Kinstler’s important volume Come to this Court and Cry, a landmark study of the aftermath of the Shoah. I’d like, though, to hone in on a remark which indicates, as it were, the book’s hermeneutic framework. ‘In Jewish tradition’, writes Kinstler, ‘law and literature have a dialectic relation, inflecting and following upon one another. Where the law fails, parables point the way. Where stories are silent, law speaks. In this way, literature and law produce and revise one another. «The two are one in their beginning and their end», wrote Haim Bialik.’ This insight helps us understand an aspect of the contemporary cultural climate. In society, but also in the Church, a movement is abroad to abolish fundamental laws. At the same time we have largely forgotten our identity-shaping stories, no longer retold. What we’re left with is bewildering emptiness.