Peregrine Falcon

The Ben Jonson epigraph, ‘Now thou but stoop’st to me’ all but sums up a poem by D.S. Martin that has accompanied me and in a way haunted me throughout Holy Week and Easter this year. It is a variation on the theme of the Hound of Heaven, though denser than Thompson’s famous text. At one level the key image is uncomfortable. The falcon is a bird of prey; its intentions are not benevolent. At the same time – anyone who has seen a falcon dive knows the reverence one feels, the stunning beauty of the spectacle. The associations evoked in a Scripture-soaked mind are relevant: we should not reduce the Bible’s likening of Israel’s God to an eagle (e.g. in Dt 32.11) merely to stuff for sentimental songs. There is exultancy and yearning in the last two lines. They seem to me appropriate for the Easter Octave. The invitation to effect a Sursum corda is ultimately an invitation to prepare for the definitive journey home, where the Risen Christ awaits us. We have here no abiding city.

The Fifth Evangelist

A reminder of my note from 2 April last year.

I think of something Elisabeth-Paule Labat once wrote: ‘there is more music in a single one of Schumann’s Kreisleriana or Kinderszenen than in an entire opera by Massenet, in a brief Bach chorale charged with mysticism than in the complete organ works, in themselves not uninteresting, of Pachelbel.’

The concentration of music, intelligence, and pathos contained in Bach’s Passions is miraculous. I have no other word for it. Jeremy Begbie has spoken of Bach’s music as ‘resonant witness‘. Justly, the Leipzig Master is known as the Fifth Evangelist.

If you want to go deeper into what we’re in the middle of on Holy Saturday, listen to this.

Choose Life

Abortion has again become a prominent subject in public debate. Norway’s Council of Catholic Bishops has just presented a statement on a proposed change to our country’s legislation on abortion. You can read our statement here. Here is a note about it on Vatican News.

It is heart-rending that reasoned discourse on abortion is often drowned in violent polemics or even sabotaged by violent gestures, as recently happened at the meeting of a pro-life student group in Manchester.

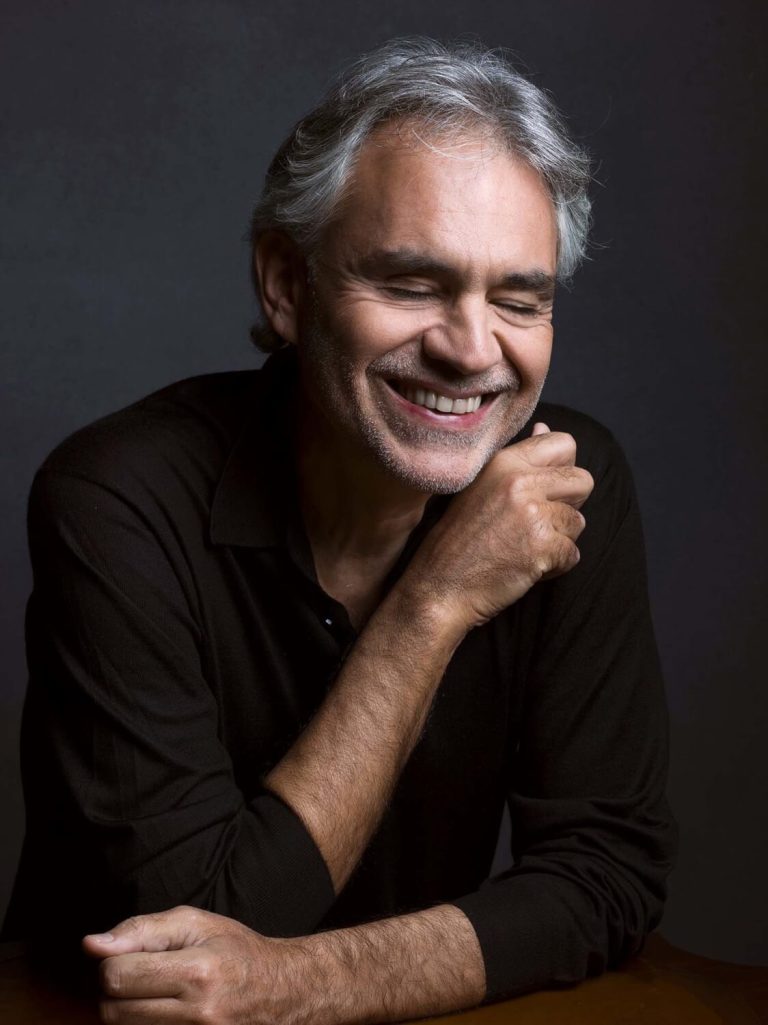

One of the most important things the Church can do, it seems to me, is to remind ourselves and others of just how complex this matter is, of what vulnerabilities are involved, of the responsibilities we carry. It is crucial to remember to see the subject from more than one angle. We need quietly authoritative statements like this one by Andrea Boccelli. Or like David Scotton’s in I Lived on Parker Avenue.

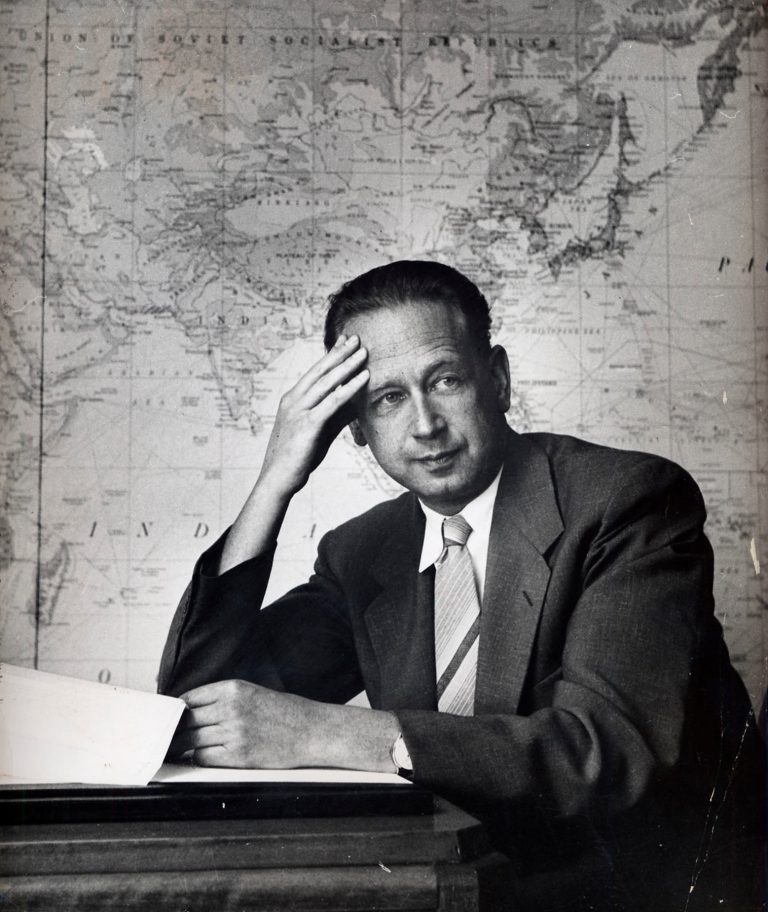

Hammarskjöld

The person, destiny, and legacy of Dag Hammarskjöld exercise perennial fascination. Interest has been nurtured in recent years by works of enquiry. Roger Lipsey’s Dag Hammarskjöld: A Life from 2015 is recognised as a watershed in scholarship. In a different register, Mads Brügger’s investigative film Cold Case Hammarskjöld (2019) opened the Pandora’s Box, hung with multiple locks, of the 1961 plane crash in which Hammarskjöld died. It signals conspiracy theories the viewer (left, as Ann Hornaday wrote, feeling ‘shockingly uncomfortable’) wishes were less persuasive. Last week Per Fly’s epic Hammarskjöld was launched in the Norwegian cinema. It raises questions – not least regarding the legitimacy of inventing a key character supposed to embody a tendency in Hammarskjöld’s life. Nonetheless, the film impressed me. I found the portrayal credible. One is left with much to think about that is of relevance. Faced with today’s array of global emergencies, one wishes one could look towards the UN as an objective arbiter fit to be an agent of peace only to discern, again and again, complexes of partial interest. The thought of Hammarskjöld prompts the question: Where on the international political scene do we now find voices worthy of our trust?

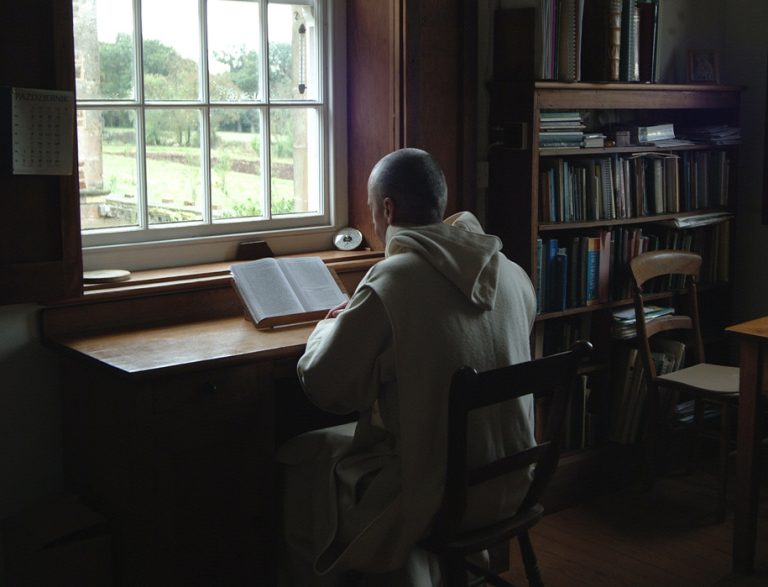

A Pastor

A recent conversation about Gregory of Nyssa’s De hominis opificio, a treatise for our times, taught me that the best Greek edition is still reckoned to be that of the Reverend George Hay Forbes (1821–75). I found an obituary of this singular man appended to a memoir of his brother. ‘An illness in early childhood had left him an incurable weakness of the limbs, […] but his ardent soul could not be satisfied without reaching onward to the highest form of service possible to him.’ This service was not least a matter of loving the Lord with all the resources of his mind. He was immersed throughout his life in the study of ancient texts. That did not make him aloof. People did not experience him as distant. This appears from the moving account of the day of his funeral: ‘While every window was darkened and every bell tolling, the whole population of the place, headed by the municipal authorities, followed the coffin down to the water’s edge where the steamer awaited it that was to convey it to the beautiful cemetery at Edinburgh. They watched the vessel quit the shore and then when they turned away there was many a touching token of the sad sense of bereavement which smote upon their hearts, as they felt that they should look upon his face no more.’

Remembering Well

In a strong statement issued yesterday, the Permanent Synod of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church recalled the importance of realism and responsible remembrance in discourse pertaining to Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine: ‘Ukrainians will continue to defend themselves. They feel they have no choice. Recent history has demonstrated that with Putin there will be no true negotiations. Ukraine negotiated away its nuclear arsenal in 1994, at the time the third largest in the world, larger than that of France, the UK, and China combined. In return Ukraine received security guarantees regarding its territorial integrity (including Crimea) and independence, which Putin was obliged to respect. The 1994 Budapest memorandum signed by Russia, the US, and the UK is not worth the paper on which it was written. So it will be with any agreement “negotiated” with Putin’s Russia.’ The synod further remarks: ‘It is worth mentioning that every Russian occupation of Ukrainian territory leads to the eradication of the Ukrainian Catholic Church, any independent Ukrainian Orthodox Church, and to the suppression of other religions and all institutions and cultural expressions that do not support Russian hegemony.’

Lætare

There’s a festive expectancy in our liturgy. The Church likens Lent to a pilgrimage. Today we stand on a promontory with a view on Jerusalem. We rejoice in the distance already covered. We rejoice that our destination is in sight. In the collect we pray for grace to ‘hasten towards the solemn celebrations to come.’ There has to be a spring in our step. We are called home. The word ‘home’ has a sweetness unmatched by any other word. Our home is not necessarily where we come from. Think of Israel: the men and women who came home to the Promised Land had never seen it before; they were born abroad. Many of you gathered here will have had similar experiences. The home you have made for yourself is premised on a departure, in some cases a painful departure, from an original home that no longer feels like home. Where am I at home? Where do I belong? These questions are crucial for us humans. They’re not always easy to answer. (From a homily for Lætare Sunday)

Rembrandt

The Jonathan Sacks Foundation, thank God, still circulates the rabbi’s texts. This week’s reflection on the Parashat Vayakhel cites Rav Kook‘s observation: ‘Literature, painting, and sculpture give material expression to all the spiritual concepts implanted in the depths of the human soul, and as long as even one single line hidden in the depth of the soul has not been given outward expression, it is the task of art to bring it out.’ Elsewhere the Rav wrote about his habit of going to see Rembrandt paintings in the National Gallery: ‘We are told that when God created light [on the first day of Creation, as opposed to the natural light of the sun on the fourth day], it was so strong and pellucid that one could see from one end of the world to the other, but God was afraid that the wicked might abuse it. What did He do? He reserved that light for the righteous in the World to Come. But now and then there are great men who are blessed and privileged to see it. I think that Rembrandt was one of them, and the light in his pictures is the very light that God created on Genesis day.’ This light, Sacks adds, unveils ‘the transcendental quality of the human, the only thing in the universe on which God set His image.’

Oikoumene

I have spent the past forty-eight hours at a pastoral congress in Sweden on ‘The Heart’s Discipleship’ organised by the journal Pilgrim, to which I am privileged to contribute as a columnist. There were over 300 participants from a broad spectrum: Lutheran, Free Church, Catholic, and Orthodox. Conferences and seminars were excellent; conversations were deep; liturgies were prayerful; the atmosphere was cordially hospitable. The fact that such an encounter is possible at a time when the wind has largely gone out of the sails of institutional ecumenism is significant. I am strengthened in a core conviction: the way to Christian unity, a Gospel imperative, must set out from personal encounters; it will proceed through friendship and mature through trust, which takes time to develop; its goal will be a deepening of life in Christ, the Truth, nothing less; its impetus will be the call to conversion; along the way shared silence will be at least as important as a multitude of words.

Silence & Darkness

Werner Herzog’s 1971 documentary The Land of Silence and Darkness is ostensibly a portrait of Fini Straubinger, a philanthropist devoted to the care and instruction of the deaf-and-blind, having herself lost hearing and sight after a childhood accident. More fundamentally the film is an induction into a mode of existence redoubtable in its intensity and abstraction. It lets us intuit the possibility of solitude so overwhelming that the mere thought of it is shocking. Herzog is a keen, unsparing observer, sometimes outraged by what he sees: certain scenes would be unthinkable in contemporary reportage. Yet there is deep humanity in his gaze, and respect for the unknown grandeur of pathos in certain destinies. The final sequence, showing a man cut off from human commerce embracing a tree, is a poetic statement at once beautiful and searingly painful. The articulate Miss Straubinger speaks of the Seelengwalt, violence of soul, afflicting the deaf-and-blind. Its specificity is incomprehensible to anyone who has not known it; yet this extreme experience points towards a universal aspect of the human condition. This film, difficult at times to watch, is deeply affecting. It raises timeless, necessary questions.

Finis terrae

On a pastoral visitation this morning to the isle of Leka at the northern frontier of the prelature of Trondheim – an island over which sea eagles fly, whose strangely coloured rocks are of a kind otherwise only found in America – I remembered Christ’s injunction reported in the Acts of the Apostles, ‘You will be my witnesses to the ends of the earth’, and thought, ‘Well, here we are’. It is impressive to encounter the austere majesty of the scenery and the gracious, hospitable kindness of a small community determinedly making a living in this place, as people have done for ten millennia. How to respond and correspond to the Lord’s missionary call? By remembering, precisely, our smallness and God’s greatness; by being humbly mindful of the long history of which we are part; by listening in quietness to the Word by which all things were made; and by believing in the Word’s continued, effective power to make the weak strong, to create something out of nothing, to heal any wounds – as today’s collect reminds us in its audacious affirmation: ‘Lord God, you love innocence of heart, and when it is lost you can restore it.’

Inhuman Intelligence

I was heartened to read Eric Naiman’s angry essay about students handing in ChatGTP-generated papers about The Brothers Karamazov. He sees in this trend a resurfacing of the Grand Inquisitor’s ruses, a cowardly relinquishing of responsibility, be it just for having an opinion, for formulating reasoned statements. Added to that, there’s the humiliation of being expecting to honour the pseudo-creations of a robotic engine: ‘Taking stock of the queasiness and rage that was overcoming me as I looked at my mounting pile of AI compositions, I understood how nauseatingly insidious the work of the machine has become.’ Some students – even at Berkeley – regard the machine’s output as a standard exceeding their own. I was struck by Naiman’s observation: ‘Eventually students who work with ChatGPT may become so adept at understanding what “good writing” looks like that they will not even need to use it: they themselves will become artificially intelligent. That won’t be an improvement, because an essay that sounds as though it were written by a computer is no better than an essay actually written by one.’

Sebald

I was given WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn as a birthday present almost thirty years ago, started it but didn’t get on with it. The book ended up languishing on my shelves until, somehow, I lost it. I had a vague sense there was unfinished business attaching to it. In 2019 I picked up Die Ausgewanderten from a second-hand book store almost as an act of reparation for negligence. These past few days I have read it at last, with a depth of emotion no book has provoked in me for a long time. Anything I might say about it sounds trite even before words are uttered. The beauty of Sebald’s prose is almost unbearable; the brittleness of the destinies he draws is affecting. The reader feels entrusted with a treasure of immense significance in the light of which his own life demands to be reread. Perhaps I needed all this time of waiting to be ready. Mark O’Connell has observed that reading Sebald is ‘a wonderfully disorienting experience’. I’d say it is no less an experience that might lead you home.

Prayer is Power

The voice of His Beatitude Sviatoslav Shevchuk remains a light in the world’s darkness. In an interview given for the second anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he reflects on prayer – and thereby outlines, too, a perspective on pastoral care whose substance, rooted in compassion, reveals the shallowness of certain current platitudes: ‘We are living in the midst of adversities, pain, tragedy, constant danger of death. There is pastoral care of people who are suffering, who are crying. Very often you can say nothing. You can only be present, cry with those people and share their pain. That pain affects you, because by sharing, you are bringing in your heart their pain. And you have to be careful what you will do with this, too much pain in your heart. This pain in a certain way contaminates you. And you have to pray. This is how we are rediscovering the importance of prayer, because prayer is not a symbol, a ritual, a simple ceremony. Prayer is a power which goes through your heart. Prayer is communion with God. Prayer is something which transforms you and the reality around you.’

Saying Yes

In a reflection on the feast of St Scholastica, Mother Christiana Reemts cited a book by Hans Urs von Balthasar: ‘Love is limitless agreement with God’s will and providence, whether this will has already been expressed or not; love is a resolute Yes in advance to everything, whatever it may be, even the cross, even immersion into absolute abandonment or forgottenness or futility or insignificance. The Son’s Yes to the Father; the Mother’s Yes to the angel, carrier of God’s will; the Yes of the Church in all her members to her sovereignly provident Lord.’ The abbess went on to observe: ‘There are statements that, when I read them, leave me with the certainty: Yes, this is exactly how it is, even though I fail again and again to live up to what they ask. Even when I rebel, justifying rebellion by appeals to ‘what is just human’ or to the example of Job, the longing to utter an unqualified Yes remains. For only that will make me truly happy.’ Cf. Notebook 6 May 2022.

Focus

Worth reading is the 2024 edition of Focus, the Norwegian Intelligence Service’s assessment of current security challenges. It states that ‘the Russian armed forces remain the main military threat to Norway’s sovereignty, its people, territory, key societal functions and infrastructure’. There is a section entitled ‘Russia’s Permanent Break with the West’: ‘Moscow expects a lengthy confrontation with the West and has identified a need for expanding the Russian armed forces. According to official plans, the armed forces will increase from 1 to 1.5 million soldiers by 2026. The Moscow and Leningrad military districts will be revived, and new units will be formed in Karelia. Russia is also set to establish several new infantry and airborne divisions. An expansion of the military structure on this scale will be a time-consuming and challenging process, particularly due to the war. Although Moscow’s plans are first and foremost political posturing, some changes may take place near Norwegian borders already this year. […] Even before the war, Russia was in the process of reducing the number of brigades and reintroducing the division level, as according to Russian thinking, divisions are seen as better suited to fighting a regional war with NATO.’

A Global View

Almost two years ago (Notebook 6 April 2022) I referenced a 2003 speech by Otto von Habsburg about Vladimir Putin. As far as I can see, this video is still not available with English subtitles. It is a pity, for it is instructive. Perhaps somebody who knows how to do this sort of thing could look into it. Anyone curious meanwhile about the relevance of Habsburg’s understanding of Russian policy might consult a paper on ‘The Globalisation of Politics’ from 2006 partially available here: ‘During the period from Stalin to Putin, Russian imperialism has always nurtured the objective of reconquering Ukraine, folding it into Russia and using it for further operations against Poland and other parts of Europe. That turns Ukraine into a critical location within Europe and necessitates its integration into the EU. This circumstance has not been considered seriously and is, therefore, dangerous. It could still be corrected today were one ready, once and for all, to recognise the need for a genuine European policy.’ Reflections in terms of ‘What if?’ are often futile; but not always. One is drawn to ask a further question: Who, now, proposes or is even interested in a genuinely European, not to mention a global policy?

Lent

Lent is a time during which to deepen our prayer. If anyone seeks advice on how to go about it, I recommend again Dom André Poisson’s text on The Prayer of the Heart:

‘I cannot possibly pray without praying in my body. When I turn towards God, I cannot abstract my incarnate reality. It is not merely a question of religious discipline if certain gestures are prescribed, if certain material conditions direct me, when I turn to God. These are pointers to the one and only truth: God loves me the way he made me. Why should I want to be more spiritual than he? This is how I shall learn to live at the level of my body with its constraints, whether I eat, sleep, or rest, whether I am ill or exhausted. Between God and me, such experiences are not obstacles.’

You can find the text in English here. Here is the French original. An unofficial Polish version can be found here.

No Eloquence

On the news yesterday, I heard an aid worker express noble rage at the idea that Israel, in view of the planned assault on Rafah, would simply send one and a half million people ‘up a country road’. The misery in Gaza is unconscionable. While remaining committed to a view that remembers the full complexity and global tragedy of the ongoing war, one cannot but be aghast at the destructiveness of the Netanyahu regime’s campaign, which makes the well-known passage from Exodus 21, ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’, appear for what it is: a disposition of justice, to keep vengeance within bounds. The other day, I happened upon an interview with Mourid Barghouti (whose I Saw Ramallah is a book to re-read at this time) from 2008. It gives much food for thought. Barghouti’s cited poem keeps ringing in my ears: ‘Silence said:/truth needs no eloquence./After the death of the horseman,/the homeward-bound horse/says everything/without saying anything.’ I also keep thinking of this piece by Ahdaf Soueif, Barghouti’s translator.

Mäkelä

For more than half a century Bruno Monsaingeon has been making revealing films about music and musicians. He has come a long way since producing his portrait of Nadia Boulanger in 1977, but the founding intuitions back then were right, they have simply matured. He has now brought them to bear on the 28 year-old Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä. We are given insight into a musical vocation marked by freedom and intelligent joy. Mäkelä’s bonhomie that does not feel forced. It seems to transmit a genuine delight in others, united by music. Striking is his respect for musicians. He is demanding, but does not shout; he is wary, he says, of using too many words. A conductor must transmit his message through presence. If he sufficiently embodies his vision, he will not need bombastic gestures. I have never before seen someone conduct an ensemble with his eyebrows. This courtesy before artistic greatness and before artists indicates a pedagogical model transferrable to other walks of life. Monsaingeon says he considers Mäkelä the greatest conductor of the 21st century. Worth watching.

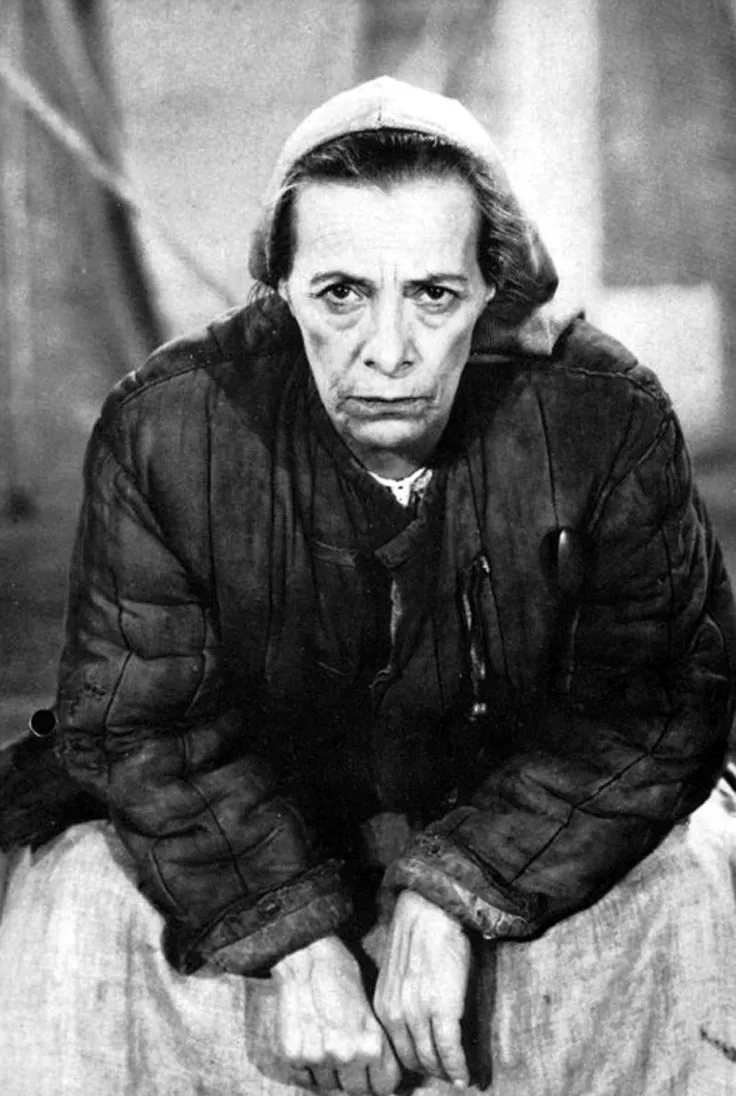

A Great Actress

No one who saw Helene Weigel (1900-71) perform seems to have forgotten the experience. Her diction, gestures, and sense of drama were meticulously equilibrated. A biographer has written that ‘Weigel’s movements on stage were employed deliberately and economically, as the actress believed that too many details would lead to an extreme naturalism that could ruin a character’. That’s worth remembering also on the stage we all share of ordinary life. Weigel’s great-heartedness was proverbial. I love the story of how she, a signed-up member of the Communist Party, took pity on the FBI agent assigned to watch her house on a bitterly cold day during her WW2 American exile, so invited the fellow inside, ‘where’, she said, ‘he could observe her more easily’. On YouTube I have found this recording sparkling with intelligence of Weigel reading works by her husband Bertolt Brecht. Oh, the mystery of the human voice! Though Weigel has been dead for half a century she becomes tantalisingly near as we hear her tell of Giordano Bruno’s overcoat, a story of tenderness, of the composition of the Book of Tao Te Ching and of the Soldier of La Ciotat. And what noble indignation in her rendering of Brecht’s Class Enemy.

Transhumance

Mireille Gansel’s Traduire comme transhumer is at once an autobiography and an essay on the translator’s art, which like all art presupposes craft. The notion of transhumance is suggestive. It refers to the practice of moving livestock from one grazing-ground to another in a seasonal cycle, permitting the finding of like nourishment differently. Gansel has dedicated her life to the translation of massive, complex works. She has rendered Paul Celan and Nelly Sachs; she has revealed the sonorous universe of Vietnamese poetry. With quiet authority she evidences rather than argues that literature has a political dimension in as much as it transgresses boundaries, making me see that understanding does not always come from drawing the other to myself, but from letting myself be drawn into it: ‘I well remember that morning when the snow was thawing and I sat at an old table under darkened beams and suddenly realised: the stranger is not the other, it is I — I who have everything to learn, to understand from him. That was no doubt my most essential lesson in translation.’

Music of Colour

When I grew up it was common to find prints of Harriet Backer (1845-1932) in people’s homes; the art of this gifted impressionist had penetrated national sensibility, had become national property. I missed the exhibition dedicated to her work at the National Museum in Oslo this winter, unfortunately. The website remains a good resource, though I suspect Backer, of whom her friend Hulda Garborg said, ‘I have never known a more contented or happier artistic soul’, would have liked to be remembered more as an artist in her own right, less as a woman breaking gender stereotypes. The exhibition’s didactic material is a sterling example of our time’s myopia, a distinct disadvantage when it comes to looking at pictures. In Oslo the show was called ‘Every Atom is Colour’. When it removes to the Musée d’Orsay in the autumn it will be called ‘La Musique des couleurs’. A happier choice. Harriet’s sister Agathe, a pupil of Liszt’s, was a composer of note; music recurs as a visual motif in Harriet’s painted interiors. More essentially, do not her very colours sing? And do we not pick up, still, a note of contentedness that has become strangely unfamiliar to us?

Zone of Interest

I have frequently been moved at the cinema; I have been fascinated, sometimes outraged; but I have never emerged from a screening feeling as battered as I did after seeing Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest. Though praise is not unanimous (you may consider Manohla Dargis’s review in the NYT, but I think she missed the plot), the film has earned great critical acclaim. There is a substantial body of commentary emerging. Sean O’Hagan calls The Zone of Interest ‘a study in extreme cognitive dissonance’. It is also an account of deliberate, self-induced moral paralysis. I have never experienced such a profoundly auditive film. The drama unfolds at two simultaneous levels: the level of what you see and the level of what you hear. It made me think of the Book of Revelation, in which sight and sound are frequently in contrast, but intelligence of the whole comes from what you hear. The sound design is by Johnnie Burn. He has remarked: ‘even though you don’t ever see the horror, it is by far the most violent film I have ever worked on’. To call this film timely is an understatement. It is necessary. I urge you to see it.

Habitus

A young nun of Ryde reflects on the religious habit, first from her perspective of seeing others wear it, incursions of otherness into the fashion-world of a modern university town: ‘While in the colourful hotchpotch everyone was trying to express ‘himself’ as best he could, the habit gave its wearer an ordering to a community, to a meaningful whole, even if only that one member of the whole was to be seen. Curiously, the habit seemed to me to emphasise the essential personality of its wearer, in contrast to the elaborately accessorised conformity I could see all around it.’ She then speaks of the experience of actually wearing it: ‘The habit reminds me continually who I am – a child of God whom the Lord has graciously placed in his service – and it demands of me that I do justice to this calling. What could better express a total self-gift to Christ than a garment which surrounds me entirely, like a second skin?’

You can read the whole piece here.