Life & Loss

At times of upheaval, it matters, for the sake of understanding, to extend one’s perspective as broadly as possible. It matters no less, at the same time, to focus on particulars, lest the complexity of seemingly insoluble conflicts overwhelm us. We read of soldiers in both the First and the Second World Wars who hankered after the novels of Jane Austen. Cinema can likewise root us in human particulars, revealing their beauty and letting us sense the universal significance within them. A master of this art was Yasujirō Ozu. His 1953 film Tokyo Story, remastered in 2017, is a fine evocation of life and loss, filial failure, selfless devotion, and the uncertainty of old age. Ozu once remarked to a reporter: ‘Pictures with obvious plots bore me.’ Tokyo Story is not a film of action, but its characters are drawn with moving, utterly credible precision. It is a work of high art that challenges viewers to reflect on what is, in fact, of consequence in life. A challenge that, here and now, is of vital importance.

Revolution

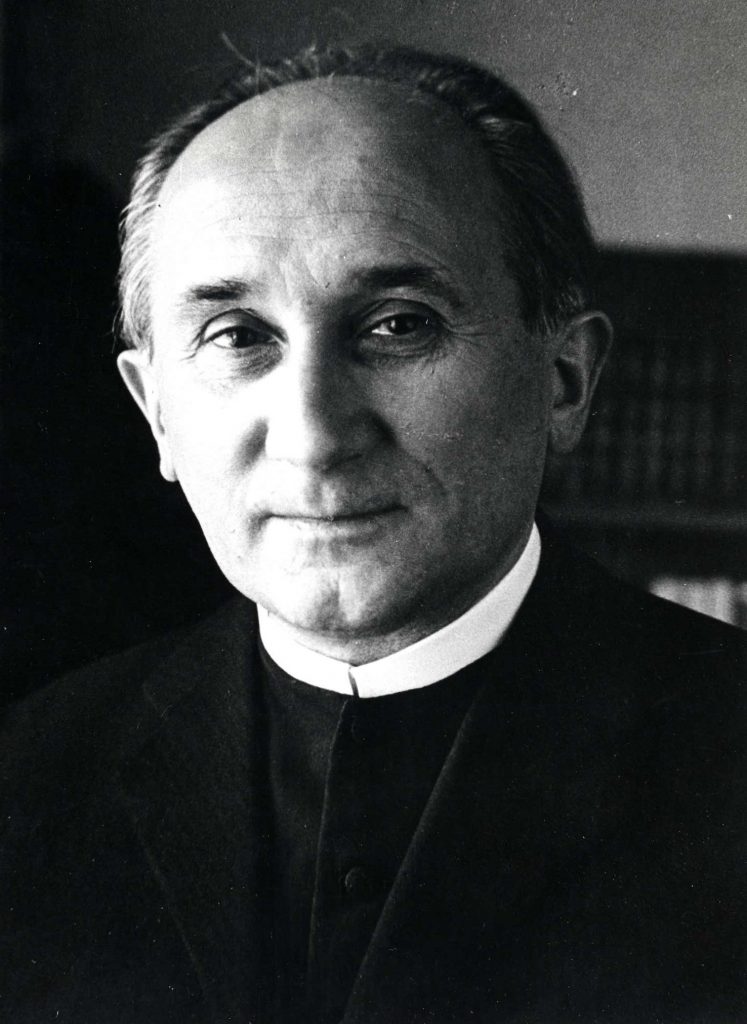

Trying to understand the background for the war in Ukraine, we are brought up against deeply troubling realisations. I have been salutarily provoked by the analyses of Professor John Mearsheimer, much cited in recent weeks in a variety of media. It is uncanny to revisit now this lecture, which he gave seven years ago at the university of Chicago, where he occupied a distinguished chair. What strikes me most is his emphasis on the fact that, to a certain way of thinking, it will seem expedient to ‘wreck’ an entire nation to ensure one’s own strategic advantage. James Meek made much the same point in a carefully argued 1 March podcast for the LRB. An agenda that coolly envisages destruction for destruction’s sake is surgically dehumanised. All the more powerful is Archbishop’s Shevchuk’s repeated pleas (here, for instance) for a focus on personhood. What is a Christian response to iniquitous violence? ‘We should do everything possible to express our respect for the dignity of the human person.’ The archbishop calls, not only for Christians’ obedience to Gospel standard. He calls for a revolution of politics.

Of the Brook

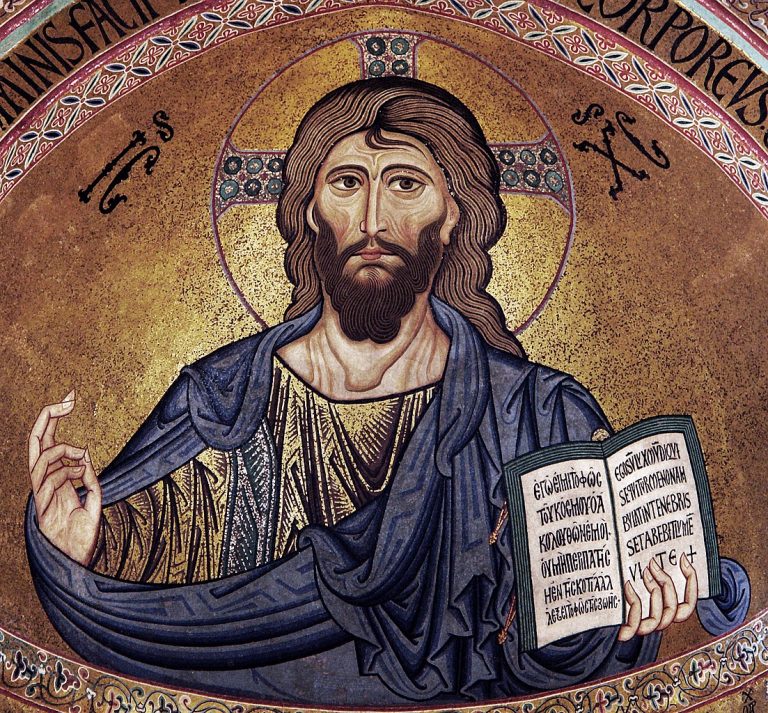

The scene of the Annunciation is rendered in any number of wonderful works of art. Dearest to me is that of the Carmelite painter Fra’ Filippo Lippi (1406-69). Rarely have I been to London without stealing time to go and pause before it in the National Gallery. The silent conversation between the Virgin and God’s Angel is depicted incomparably. The essence of this feast, however, the fact that it commemorates the moment in which the Word became flesh, is impossible to render pictorially. For that, we need music. An account is given us in Handel’s Cantata Dixit Dominus, a setting of Psalm 109. The Psalm’s finally verse reads thus: ‘He shall drink of the brook in the way: therefore shall he lift up the head.’ The Fathers found in this phrase a prophecy of the incarnation, of God’s stooping to drink of the water that quenches our thirst along life’s tortuous, beautiful, often painful path. This version, sung by Annick Massis and Magdalena Kožená, takes us as close to the heart of the mystery as it is possible to get by sensory means.

Poetry

Wisława Szymborska was once asked by an aspiring writer to provide a definition of poetry. She answered with kindly irony:

‘A definition of poetry in one sentence — please. We know at least five hundred from various sources, none of which strike us as both all-embracing and pleasingly precise. Each expresses the taste of its own age. Our native scepticism saves us from attempting new definitions. But Carl Sandburg’s lovely aphorism comes to mind: “Poetry is a diary kept by a sea creature who lives on land and wishes he could fly.” Will that do for now?’

From Szymborska’s Advice for Authors, translated by Clare Cavanagh.

Flying

For years I have admired the films of Volker Koepp chronicling life in the region the ancients called Sarmatia, stretching from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The fact that this region is now largely covered by Ukraine give Koepp’s work great relevance. Indeed, I’ve just noticed that his 2013 film In Sarmatien will be re-screened tomorrow in the Akademie der Künste in Berlin at a fundraising event for the Ukraine-Hilfe. The film portrays tensions of a life lived between Russia and Europe. A Moldavian woman recounts how not so long ago her mother tongue, Romanian, for being a Romance language related to Italian, had mandatorily to be written with cyrillic letters. It is chilling, in the light of current events, to hear a young Ukrainian say, nine years ago, that after the hopes raised by the orange revolution, ‘great pressure’ had set in: ‘Everything gets smaller, narrower. There’s straightforward intimidation going on.’ At the end of the film, though, an interviewee maintains: ‘Anyone who carries a sentiment of freedom in the heart, in the soul, can fly.’

Castissimus

‘Being a father entails introducing children to life and reality. Not holding them back, being overprotective or possessive, but rather making them capable of deciding for themselves, enjoying freedom and exploring new possibilities. Perhaps for this reason, Joseph is traditionally called a ‘most chaste’ father. That title is not simply a sign of affection, but the summation of an attitude that is the opposite of possessiveness. Chastity is freedom from possessiveness in every sphere of one’s life. Only when love is chaste, is it truly love. A possessive love ultimately becomes dangerous: it imprisons, constricts and makes for misery. God himself loved humanity with a chaste love; he left us free even to go astray and set ourselves against him. The logic of love is always the logic of freedom, and Joseph knew how to love with extraordinary freedom. He never made himself the centre of things. He did not think of himself, but focused instead on the lives of Mary and Jesus.’

From Pope Francis’s Apostolic Letter Patris Corde, n. 7.

Laughter

Is it licit, even possible, to laugh in the face of tragedy? In a thought-provoking essay in The New Yorker, Adam Gopnik contends that it is. He reflects on the communication of Ukraines’s president Volodymyr Zelensky, that paradoxical politician, whose background is a career in comic acting. He cites something Zelensky said in an interview in 2019: ‘Laughter is a weapon that is fatal to men of marble! You shall see.’ Gopnik muses: ‘Clowns degrade order in order to make us imagine another world.’ This can have a sublime dimension. It is significant that Russia, with its long tradition of absolutist rule, should have produced the singular type of the holy fool. Gopnik’s observations make me think of a remark made by Jonathan Sacks in a broadcast produced at the height of Covid anxiety. He was commending people able to make others laugh about what was going on. For, he insisted, ‘humour is deeply connected to humanity. […] What we can laugh at does not hold us captive in fear.’

Compassion

On 25. March, the feast of the Annunciation, Pope Francis will consecrate Russia and Ukraine to the immaculate heart of the Blessed Virgin Mary. This is a powerful gesture, symbolically charged, right now. The archbishop of Lviv, Mgr Mieczysław Mokrzycki, invites us all to take part in spiritual preparations during the days ahead. In the prelature of Trondheim we use a novena that concludes with the following prayer:

Eternal Father, in the maternal heart of the Virgin Mary you give us an image of perfect compassion with your Son’s saving sacrifice; grant us a heart like hers, and let the Russian and Ukrainian peoples, at her intercession, be blessed in justice with your peace, which is not of this world. Through our Lord Jesus Christ, your Son, who lives and reigns with you in the unity of the Holy Spirit, one God for ever and ever. Amen.

Mystery Mislaid

At Lauds this morning, I rejoiced on reading one of the preces. Truly a prayer for the present moment! Here it is: ‘Da nos mysterium Ecclesiæ altius percipere, ut eadem sit nobis et omnibus efficacius salutis sacramentum.’ We pray for the gift of being able to perceive – to fathom intellectually – the mystery of the Church more deeply, in order that the Church may more efficaciously be for us and for all a sacrament of salvation. Just out of interest, I looked up the prayer, afterwards, in the English breviary. There it reads as follows: ‘Lead us more deeply into the life of your Church; and through us make it a clearer sign of the world’s salvation’. It’s like boiling good pasta down to mush before serving. The mystery is gone. The sacrament is gone. Perception – the summons to exercise one’s mind so that it might open one’s being to grace – is gone. Instead of the Church, Body of Christ, being for us and for all a sacrament, agency is lodged in us.

In this simple example of sense lost in translation, the source of much current malaise can be found. We should heed, then, the 2. Vatican Council’s watchword and return to the sources.

Trust

With monastic simplicity of means, this commemorative display in the Carmelite monastery in Tromsø, Carmel Totus Tuus, says what needs to be said.

The blue-and-yellow ribbons, representing Ukraine, touch the roses’ thorns — and the roses, of course, indicate the promise of intercession for the world given by St Thérèse.

They are overlooked by a representation of Divine Mercy painted for the nuns by W. Piwarski:

Jezu, ufam tobie.

Jesus, I trust in you.

The World’s Form

I’ve felt a need to re-read Gertrud von le Fort’s Hymns to the Church. What texts! Here’s an excerpt from her prose poem Corpus mysticum:

‘Behold, you come towards us, your forehead golden with the mirror image of our joy. For he from whom we went forth has pursued us; and he from whom we scattered has gathered us to himself. In the womb of our misery, he caught up with us. He has made himself, in your hands, into humility. He lives in your chalices’ wine, in the white bread on your altars. You let him rest upon our longing. You let him rest on our hungry lips. Deep in the heart of our solitude, you let him rest; it bursts open, then, like gates whose seals are torn; the dust of atoms wafts into one, for eternity’s quiet has strength that surpasses the tempest’s: we are of one Body, one Blood. Of one ensoulment we are the flame. You are the world’s only form.’

Pain of Leaving

In a brief interview, Larisa Galadza, Canada’s ambassador to Ukraine, speaks of her experience of the past few days with consummate diplomatic discretion. Yet passionate commitment and humanity shine through, not least in her silences.

After having to flee Kyiv, she and her staff spent some days in Lviv:

‘You could see every morning the relief on the faces of the staff at the hotel because we were still there, and that gave them confidence. The morning we decided we had to leave, those faces changed. And that was heart-breaking… That was heart-breaking. I think a lot of us cried for a lot of the journey out of the country.’

Humanity

Today’s statement by the Major Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Sviatoslav Shevchuk, is a powerful summons. It shows up the hollowness of much other, contemporary discourse concerning what the Church is about.

‘Today in Ukraine we see a huge disdain for human dignity. Humanity is being destroyed, the human being is being dehumanised. Especially the being of those who began this war. He who begins war becomes lesser with regard to his own humanity. He who kills another destroys first of all humanity within himself, he destroys his own human dignity. What can we, as Christians, do to oppose such contempt for the human person during the war in Ukraine? First of all, today we should undertake acts of mercy. We should do everything possible to express our respect for the dignity of the human person.’

How to counter contempt? Undertake acts of mercy. This is life according to the Gospel. And we all need to hear it.

In Charge?

This afternoon, on the pier in Tromsø, I was intrigued to find this cast-iron dachshund. It looks out over the bay as if surveying its domains. I have no idea what it is supposed to symbolise, but it made me think of an observation by Jerry Seinfeld. Cited in En Liang Khong’s TLS review of Chris Pearson’s Dogopolis, it voices a quandary that must have occurred to many of us at the sight of dogs, increasingly wearing designer clothes, out for a constitutional with their attendants:

‘If you see two life forms, one of them’s making a poop, the other one’s carrying it for him, who would you assume is in charge?’

I probably shan’t read this study of ‘the emergence of a new kind of canine cosmopolitanism’. Life is short.

Debased

A friend has passed on some words Sara Lidman spoke on 11 November 1956, in the wake of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary. They keep ringing in my head, troublingly.

‘Time and again during these days that seem as long as entire years, one thinks: But surely this can’t be allowed to take place? Surely someone will eradicate this injustice? Must not nature itself take action against this evil? At times the state of being human is so debased that we’d sooner appeal to the clouds and the grass to show man mercy than to men. Oh, that we were reading of this barbarism in some old manual of history; that we could look up from the text and say: How cruel men were in days of old. Something like this could never happen now! But what we read is the daily paper. And we tremble for grief and shame.’

‘Truth’

The Russian president claims he has ordered the invasion of Ukraine to ‘denazify‘ the country. The Patriarch of Moscow, meanwhile, maintains that the invasion has metaphysical significance and somehow represents a moral crusade. It is hard not to draw a line between such statements and the business venture of a former president of the United States: a social medium in which subscribers can post any idea that happens to float into their mind as a ‘truth’, expecting this to be picked up and transmitted by others as a ‘retruth’.

During Lent we reflect on Christ’s words: ‘I tell you, on the day of judgment you will have to give an account for every careless word you utter’ (Matthew 12:36). There is nothing to suggest that this was intended as a throwaway remark, that is, a ‘truth’ in the social-media sense, requiring inverted commas.

Expropriation

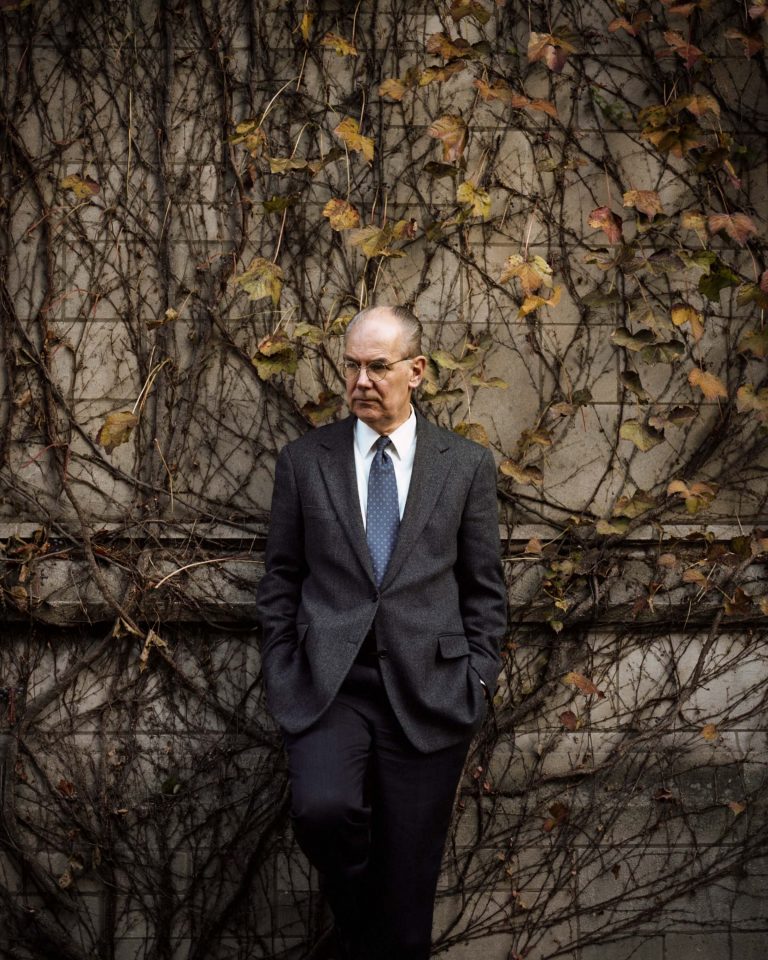

In an essay printed in the latest edition of Communio, Nicholas J. Healey performs an exegesis of ‘synodality’. He puts the term in context and provides what is often lacking: a carefully worked-out ecclesiological foundation. The following is just one of several helpful insights:

‘the coresponsibility proper to the laity unfolds in and through configuration to the ecclesial Bride — a configuration essentially requiring an obedience to the Word of God, which the Magisterium exists to foster and protect. Far from being a form of slavery to clerical overlordship, however, this obedience is an implication of the freedom of God’s children — just as the Magisterium is not the private good of clerics but a service of the deposit of faith that demands the most radical expropriation for the sake of the bonum commune on their part.’

The Place to Be

Professor Kristin Aavitsland has permitted me to share her impressions from a visit to Santa Maria della Pace in Rome last Friday: ‘It was the place to be on the first Friday of Lent, a week after the invasion of Ukraine, even if we’d turned up on a scholarly errand. A fervent, protracted rosary for prayer was going on, suitably enough in just this church. In a strange way it was as if the people praying, women almost all, were united to the saints who are depicted there so wonderfully. They too are predominantly women, women of prophecy and action, who by words, writings, and deeds stood up to tyrants, reproved the mighty, and risked their lives for the sake of justice and peace: Catherine of Siena and her namesake from Alexandria, Birgitta of Sweden. Within the spatial whole of the church they enter into a kind of dialogue with Raphael’s sibyls, likewise prophetic presences. At the heart of it all, of course, is Our Lady of peace. Above the entrance to the choir there’s an inscription: In terra pax. All this, the inscription invoking peace, the frescoes, the intense prayer for Mary’s help, brought the choir together in a single tonality. It was beautiful and soul-stirring. I think the students of the history of art were also touched. God help us for what is going on in Ukraine.’

The Pity of War

Following news from Ukraine, one can feel overwhelmed. It matters to root the tragedy in human particulars, as the BBC’s Jeremy Bowen did this morning, reporting from a railway station in Kyiv (from 11:35). ‘Fathers stood on the platforms waiting to see their families off. […] A man called Alexander sobbed as he waited for the train to leave. He’d put his wife and two small children on board. Alexander wouldn’t let go of a small toy ambulance his eight year-old son had given him as he put them on the train. He kept playing its siren. All the heartbreak of the war was on one man’s face. […] Many of the volunteers are young men, boys barely old enough to shave. […] They were dressed for a camping weekend or a festival, except they were carrying newly issued Kalashnikov assault rifles. One had brand new white trainers. Another had a yoga mat to sleep on. If they were scared, they didn’t show it. Like the other young men with them, they had the courage, patriotism, and sense of invincibility of all the other generations who have signed on to fight for their countries in Europe’s war. Their families will pray they will not have to learn the same brutal lessons. The older men looked much more apprehensive.’

Bishop’s Babble

I’ve been kindly invited by the association of Norway’s Catholic Youth to record brief reflections for Lent under the flattering title ‘Bishop’s Babble’.

There’ll be a weekly contribution (in Norwegian) every Friday until Easter. You can find the series here.

Prayer & Fasting

People often ask: How can I learn to pray? The obvious answer is: pray with the Church through the liturgy and sacraments.

However, a more intimate life of prayer is also called for. We long to pray in a way that expresses our deepest being. We long for the prayer of the heart.

I have found invaluable guidance in a slight volume published in French in 2001. Its title was, ‘The Prayer of the Heart’. Its author was designated as ‘A Carthusian’.

As an offering for Ash Wednesday, I would like to share a translation of this precious resource. You can find it here.

‘Lord, teach us to pray!’ (Luke 11:1).

The Way We Look

Still on the subject of the way we look at things, I’ve revisited Sam Mendes’s film from 1999, American Beauty. I was troubled and fascinated by it at the time, to the extent of presenting a paper on the movie to a theological society. I agree with what I said then about Mendes’s exploration of the boundary between the virtual and the real. The film ‘provides paradigmatic evocations of human beings frustratedly seeking the Other in each other, in the natural universe, and in God, wanting to transcend themselves in love, but repeatedly falling back on a painful, pitiless solitude in which ‘you can rely on no one except yourself’. Faced with such existential anguish, theologians have a duty to engage anew with essentials, telling again the story a God who does ‘look right at us’ and who does invite us to look back, not with a ‘demonic’ gaze set to dominate and possess, but in an ‘angelic’ serenity which freely admits the freedom of the Other, whose Beauty is boundless communion.’

You can find the full text here.

Sight

Some words Jean-Louis Thiériot wrote for Le Figaro this weekend resound in my mind: ‘In Europe, war is back. Our seventy years of peace have been nothing but a happy parenthesis. Only simpletons will be astonished. The warning signs were clear to behold: ex-Yugoslavia, Georgia, Donbas, Nagorno-Karabach. Power and the sword reestablished themselves long ago as the world’s axis. The apostles of the end of history and of happy globalisation were not, however, disabused of their illusions. They had forgotten what Péguy once insightfully said: ‘We must always speak that which we see; above all, we must always, and this is more difficult, see that which we see.’ They had forgotten, too, that history is tragic and that the gordian knot is often cut in blood.’

‘Lord, that I may see!’ is a culminating prayer in the Gospel. Sight is, a lot of the time, neither comforting nor comfortable. But it’s by seeing that we establish ourselves in reality and, so, are able to address it.

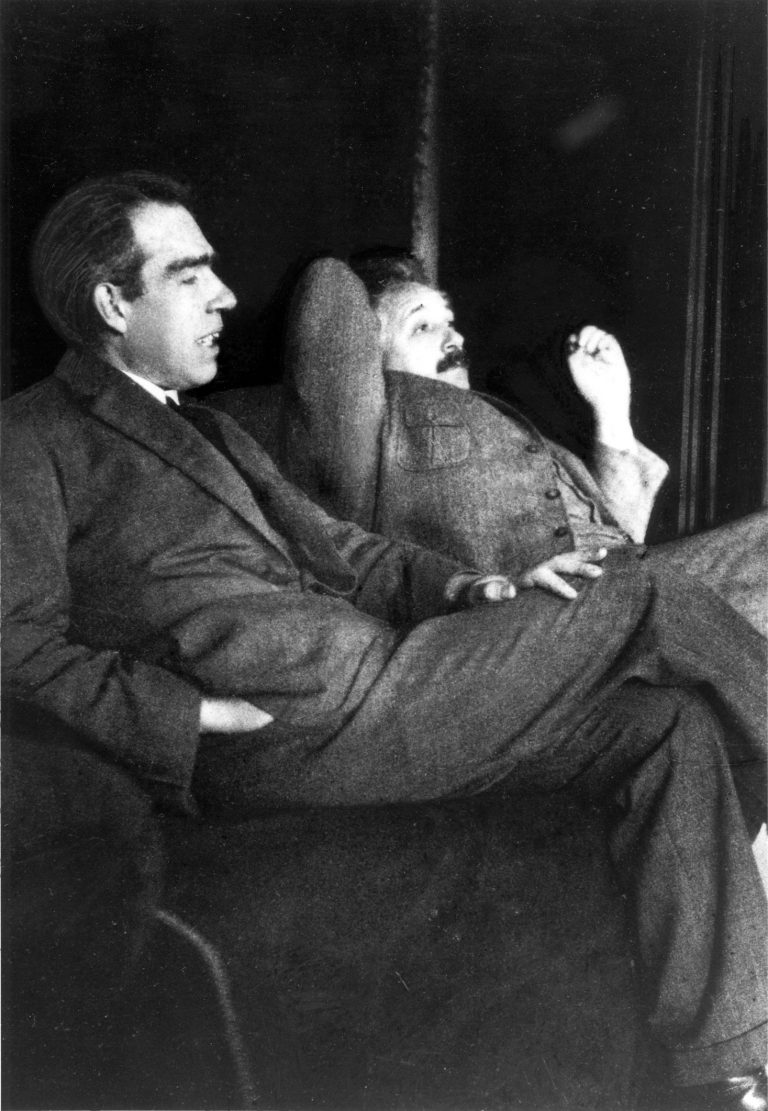

Interaction

In the austere definitions of theology, it is sometimes said that the mystery of the Blessed Trinity can be expressed in terms of three subsistent relations. It is not, to put it crudely, about three Persons with relationships; relation is the foundation of Personhood. The idea that originating reality is relational seems dizzying at first. Gradually it liberates thought. It is susceptible of transposition into the realm of human experience and psychology. Quantum physics uses a related paradigm to explain the physical world. It is fascinating to read the following in a book by Carlo Rovelli: ‘[The equations of quantum mechanics] remain mysterious. They do not describe what happens to a physical system, but only how one physical system is perceived by another physical system. What does this mean? Does it mean that the essential reality of a system is indescribable? Does it simply mean that there’s a part of the story still missing? Or does it mean, as I think, that we must accept the idea that interaction is reality?’ In a 2017 interview, Rovelli specified that ‘objects are just the nodes of interactions. They’re not a primary thing; they’re a secondary thing, I think.’ To think like that is to re-think everything.

Autonomy = Freedom?

Romano Guardini was the subject of Pope Francis’s doctoral research. It has often been said that his influence on the pontificate is great. One listens attentively, then, when one of the finest living experts on Guardini, and his biographer, comments on trends in the Church. In a recent conference, Professor Hanna-Barbara Gerl-Falkovitz offered a global perspective on the Synodal Path, in which she participates with vigour and intelligence. It unfolds, she observed, in a context that absolutises autonomy. Our sense of autonomy is now so strong ‘that whatever God (or the Church) puts before me in terms of commandments, counsels, or wishes is defined as heteronomous. Only when it accords with my own autonomy will I follow it.’ We say no to self-transcendence. We assume that freedom affirms itself against God, perceived as an Adversary — or simply refashioned in our image. Largely lost are light-charged, revealed notions of God and humanity. We’re surrendered to our own obscure longwindedness. Our time’s radical questioning, says Gerl-Falkovitz, is like a thermometer revealing an infection that has long, perhaps since the Enlightenment, been latent. It would seem that what we really need is not self-help, but a Physician.